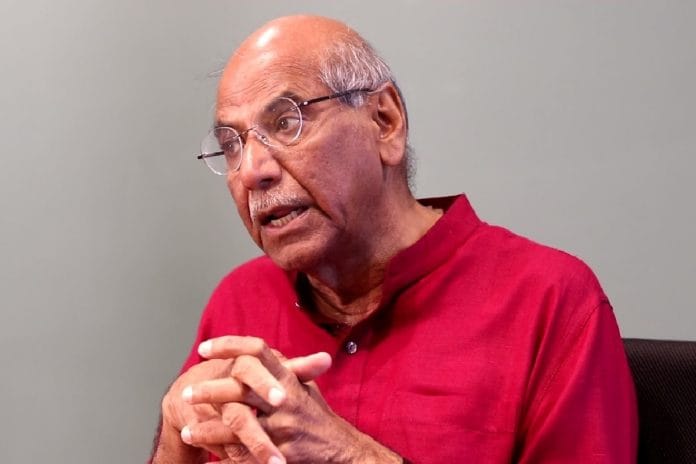

Ex-foreign secretary Shyam Saran says just like in Doklam, the Chinese use small but incremental moves to exert power, and the dilemma is when to react.

China is the biggest diplomatic challenge India faces today, and the recent crisis at Doklam is an example of it, according to former foreign secretary Shyam Saran.

“This challenge is likely to only grow,” said Saran in conversation with ThePrint journalists Monday.

Saran said in his new book, How India Sees the World, he has explained how, in emerging as a greater power in the world today, China is harking back to its rich history – in which it was a dominant and uncontested power in Asia. However, in the present global context, China’s growth as a regional power clashes with India coming to the fore.

“As China’s footprint is expanding westwards and India’s footprint is expanding, particularly eastwards, it is bumping up against what China sees as an expansion of its interests,” Saran said. “How do we reconcile the aspirations of two of the rising powers in Asia?”

This friction between India and China hit a new high during the recent Doklam standoff. And Saran said while the standoff itself was only a recent escalation, the Chinese had been incrementally increasing their presence in the area for decades.

Saran said the Chinese first started encroaching upon the Doklam plateau at the tri-junction of India, China and Bhutan by first sending graziers in 1983. Having eventually pushed Bhutanese graziers out of the region, the Chinese first built a dirt track, and then a jeep track, on which patrolling began.

These actions were well within the Chinese playbook of exerting power, Saran explained.

“Each move is not threatening enough for your adversary to react. But through a series of these incremental moves, you cumulatively come to a point where the facts on the ground have changed. Then to try to react and reverse that is much more difficult. The dilemma always is: ‘at what point do I react’?”

In the neighbourhood

Saran, who served as India’s ambassador to Myanmar, raised concerns about the Rohingya Muslims crisis. While recognising the difficulty of the situation, he maintained that deporting the refugees from India was not in keeping with India’s traditions and commitment to human rights.

“I am not quite sure how India can in some way assist with the challenge that Aung San Suu Kyi faces with the Rohingya issue, but it is not a simple one,” he said.

However, with respect to India’s most significant neighbour Pakistan, Saran said the government must rethink its current policy, and construct a more enduring framework. Terming the stop-start dialogue process between the countries a ‘cycle of dialogue and disruption’, he underlined the importance of people-to-people exchanges.

“I think the attitude should be ‘open the gates wider’, rather than close those gates every time there is tension between the two,” he said. The retired diplomat went on to say that India must take advantage of the fact that Pakistani writers and artists want to launch their books or perform in India, so that the two countries can engage more meaningfully,” he said.

Modi’s personal touch

Saran said Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s foreign policy was based on three key points: placing emphasis on personal diplomacy, understanding the importance of the economic effects of foreign policy, and giving importance to the neighbourhood, so that India could play a meaningful role in the region.

On being asked for a comparison between Modi and Manmohan Singh’s style of functioning, Saran said the latter had a longer term perspective on issues.

“I certainly thought that Dr Manmohan Singh had a much more longer-term perspective on issues, much more understated in that sense, working in a political environment much more challenging than perhaps Prime Minister Modi has to, because he has the luxury of parliamentary majority,” he said.