Fatehgarh Sahib, Ludhiana: An engineering college and a university in Punjab’s Fatehgarh Sahib are struggling to take off. They have tried everything – promising placements in tier-1 cities and scholarships worth Rs 2 crore.

But Punjab’s youth are just looking the other way: toward the seductive charms of Canada.

About 60 kilometres away, in Ludhiana, the story is a bit different. Firms in “India’s Manchester” are reluctant to hire local graduates. The training, in both private and government colleges, are not up to the mark to equip the young men and women to market standards, say business owners.

Between the stories of Ludhiana and Fatehgarh Sahib lies Punjab’s chronic unemployability problem.

Punjab’s youth no longer find education a path to a secure, successful future. Professional degrees don’t ensure high-paying jobs, not even to recover the amount spent on education.

With no innovation since the Green Revolution, agriculture has stagnated. Industries haven’t moved up the value chain and transitioned to globally aligned knowledge-based sectors that can generate high-paying jobs. The state’s role models today are from popular entertainments, not global CEOs and start-up unicorns. With singers and actors glorifying life abroad, young people are perennially trapped in disenchantment with their state and in an irrational yearning to migrate.

Omkar Pahwa, managing director of Avon cycles, experiences this problem on a daily basis. His 71-year-old business that manufactures 150 kinds of advanced bicycles employs over 1,500 people at its Ludhiana factory. But quality workforce is hard to come by.

“Students come to us with engineering degrees and they cannot even take measurements on a vernier calliper, a basic tool of an engineer. They can’t even write a leave application in English,” Pahwa says.

Across businesses in Ludhiana, owners express a similar sentiment. The mushrooming of private universities, say businessmen in Ludhiana and Chandigarh, are only handing out degrees without any practical knowledge.

“Punjab youth are absolutely unemployable,” says Ashpreet Sahni, a first-generation businessman who started his company in the automobile industry in 2014. “The curriculum in most of the colleges is obsolete and they are paid less because they know nothing.”

A regular speaker at colleges, Sahni says that the research by most of the students has no sync with the industry. “They are not assets for the companies here.”

An economist and educationist, Professor Bhura Singh Ghuman, former vice-chancellor of Punjabi University, Patiala, explains that the two sectors — industry and education — have always grown in the state without being linked to each other. As a result, the educational institutes are preparing the youth without knowing what the market requirements are.

Ghuman says it took months for universities in Punjab to introduce a module on GST and demonetisation, the two big recent economic decisions in the country.

For graduates fresh out of college, the workforce is a rude awakening. An engineer in Punjab starts at anywhere between Rs 10,000-12,000 a month.

“After spending Rs 10-15 lakh on education, students don’t want to settle for salaries of Rs 10,000. Most don’t get jobs based on their qualifications. This is a big demotivating factor for them to do well in academics. They feel that if they go abroad, they would at least get a fixed minimum wage,” says Rohit Jhajharia, who has a Masters’ degree in civil engineering and is working in a government office.

Most of all, it is the sheer inability of the young to imagine and invest in a future in the state.

In a Fatehgarh Sahib village, Karanveer Singh wiles away his time dreaming of making it to Canada one day. He saw no point in studying after completing class 12 and enrolled in an IELTS coaching instead.

“I did not go to college because I know I will not get a job. There is no scope in Punjab. So why spend time studying? I want to go to Canada,” says Singh.

Though he doesn’t dismiss the quality of education in Punjab’s colleges, he says that unless the government offers jobs to the youth, he doesn’t see any future here.

“The salaries in the private sector are only Rs 4,000-5,000, which is nothing.”

Also read: After Punjab, now Haryana youth fleeing to US–by any ‘donkey’ means possible

Industry stagnation

Harmanjit Singh’s humiliating experience at the 2013 Eurobike Expo in Germany pushed him to change the way he did business. His company Navyug Namdhari Enterprises, which his grandfather started in 1951, manufactured bicycle parts. He was one of the early businessmen of Ludhiana. Singh was proud of what his family had built.

At the trade show, when Singh, among people of other nationalities, was taking photographs of a bicycle, the representative asked him to stop.

“You Indians are here only to copy, not to buy,” he said to Singh. After the initial shock and many sleepless nights, he decided to change this perception.

“It felt wrong. This was an insult, not just to me but to India,” Singh told ThePrint. “We had to prove to the world that India can make something.”

Today, Navyug manufactures high-end bicycles under the brand name Verdant and exports it across Europe and the US. Housed in the core of India’s cycle industry in Ludhiana, which gave the country bicycle brands like Avon and Hero, Singh gauged the changing demands of bicycles in time. This innovation, he says, is keeping the companies afloat.

But that innovation has not seeped into every sector of Ludhiana’s industry, explains Rahul Ahuja, owner of Rajnish Industries, which produces automobile parts and has a presence in the hospitality sector as well.

“In most of the companies in Ludhiana, technology advancement has not happened. A company which was manufacturing fasteners and hand tools 10-20 years ago is still producing that,” says Ahuja.

Over the years, as the existing businesses in Punjab expanded, they found cheaper, viable options out of the state, says the head of an industrial association in Chandigarh who did not want to be named. The Trident Group chose Madhya Pradesh when it decided to expand its bedsheet manufacturing business with a new plant.

Punjab’s industry has its share of disadvantages. It is a land-locked state with fertile land, which pushes up the cost of buying land and transporting raw material and finished goods to ports. In the absence of any state subsidies like tax holidays, land banks and free electricity, Punjab loses the competition to neighbouring states like Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, or Uttarakhand.

Poor international connectivity and law and order disturbances in the state like drug menace, street protests, gang wars and broad daylight shootouts like that of singer Sidhu Moose Wala, discredit Punjab’s image of a stable state, which becomes a disincentive for the investors, explains Ahuja.

In 2020, he was made head of the industry vertical of expert groups formed by then-CM Amarinder Singh to chart out a growth strategy for Punjab. To accelerate industrial growth, he recommended the government invite big companies, give land and tax subsidies, and bring high-technology innovation in the existing manufacturing units to match global standards. But there was no action on his report.

“Men and women in Punjab want to work. We have human resources. We have been telling successive Punjab governments to bring a big industry here. Peripheral industries and new skills will see natural growth around it. This is how many industrial towns in the country have grown,” says Ahuja.

Besides, Punjab being an agrarian state, the industry here could never reap the benefits of liberalisation, explains Prof Ghuman. Not only the southern states like Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh raced ahead in the two decades after economic reforms, even Noida, Badi and Gurugram have set up IT parks and manufacturing hubs.

“When Bangalore and Hyderabad were developing, nothing was happening in Punjab. The mobile industry shifted out of the state and social factors like drug addiction and militancy disturbed the state for a long period. This hampered private investment from flourishing here,” explains professor Satyapal Sehgal, former head of department, Hindi, Panjab University.

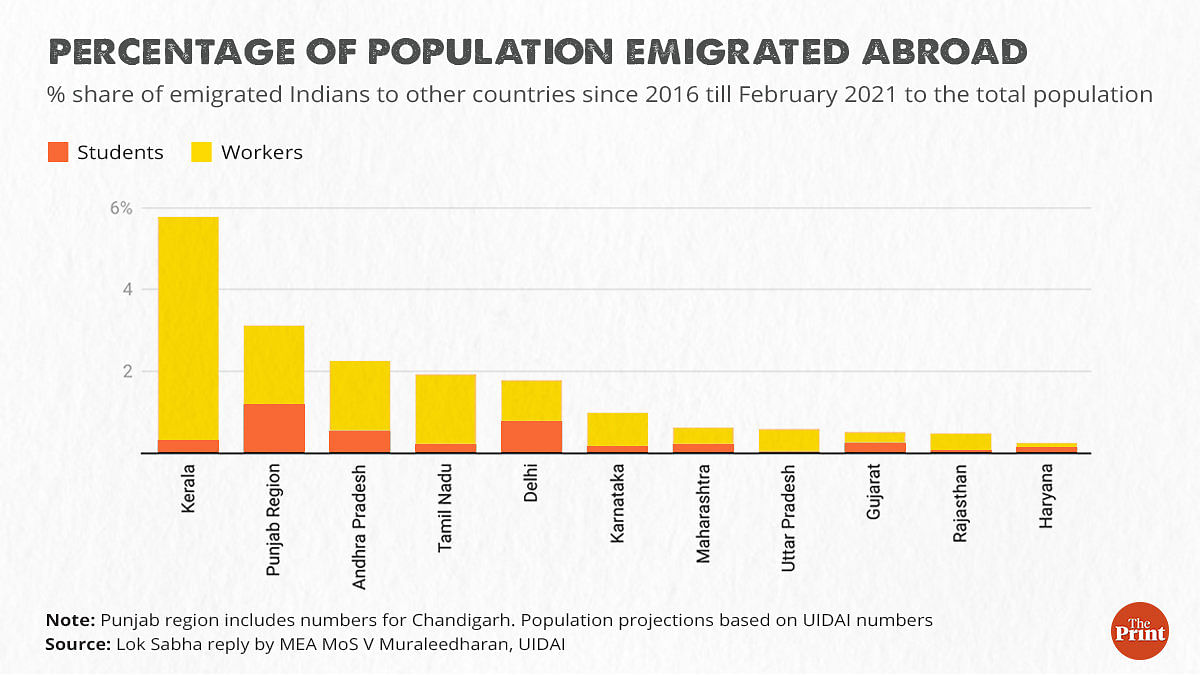

Punjab doesn’t have a vibrant IT city, like many other states. The youth here have their eyes fixed on the West, but not the same way the IT engineers from Andhra Pradesh do. Punjab’s youth are not on a quest for an H1B visa; they just want to migrate by hook or crook.

From the mid-1960s to the early 1990s, agriculture drove Punjab’s development and brought great prosperity to the state. Per capita income grew, but the state has no alternate model of development once agriculture-driven growth stagnates, says Ghuman.

“If the buying capacity of the state is increasing, it does not mean that the industry will automatically shift here. Punjab may be one of the highest consumers of mobiles and automobile goods, but these are not domestically produced. Punjab is not a self-contained model of development,” he adds.

That drive and the push to enhance industry in Punjab is absent.

Also read: ‘Few jobs, bad pay, so why should we stay’? Behind Punjab youngsters’ rush for IELTS, migration

Dearth of knowledge-based industry

To bring innovation in Punjabi University, Patiala, where Ghuman was vice-chancellor from August 2017 till his resignation in November 2020, he introduced Bachelors and Masters’ level courses in artificial intelligence and data science in 2018. It was in line with the emerging 10 sectors globally and he wanted his students to be future-ready.

But the courses did not take off.

“Though children did show interest gradually, I realised that the administration and the faculty were not ready for change,” says Ghuman. There were hurdles at every step from lack of guidance to resource crunch. “The university could not offer proper infrastructure,” he says.

The university later merged AI and data science courses with computer science.

Efforts have also been made by the Punjab government to bring knowledge-driven industries, but these too have failed.

In 2018 , the government set up a start-up hub in Mohali. But instead of high-tech software companies, the complex now houses BPOs (call centre firms), employing young men and women from Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Punjab with salaries anywhere between Rs 10,000 and Rs 25,000 a month.

“Most of those working here have college degrees but could not find jobs elsewhere. Their salaries are like pocket money till they gain experience and find better paying jobs or move to Canada,” says Nalin Rana, who works at one of the BPOs.

If Punjab, as Seghal puts it, is an ambitious state, then aspirations remain unfulfilled within its borders.

“The youth in Punjab want a lavish life and they want it without guilt. They also do not want to do menial jobs that have no pride,” says Sehgal.

White-collar jobs are the answer, but they are largely non-existent in the state. Karnataka has Infosys, Hyderabad has Google, and Mumbai has headquarters of legacy conglomerates. Punjab draws a blank.

“When the youth enter the job market, they want to join big names in the biotechnology or automotive sector, but in Punjab, they instantly feel a deficit of white-collar jobs. Neither big companies have their corporate offices nor plants,” says the industry head who does not want to be named.

Also Read: Fund my studies, I’ll get you to Canada — Now Punjabi men are being abandoned by NRI wives

Agri sector isn’t attractive anymore

Industry is not the only sector in Punjab that is deprived of innovation. Farmers still mainly produce wheat and paddy even as their income has been falling and land holdings shrinking over the years. For Punjab’s youth who aspire for a lavish, comfortable life, these shortcomings make the agricultural sector a no-go zone.

“Inflation has driven the cost of farming up. The price of diesel, pesticides and fertilisers, hiring tractors and transportation, all has gone up. And the income from the produce has not increased,” says Jasbir Singh, Wadala Johal village, Amritsar.

Falling water tables and splitting of land as families grow bigger are limiting the annual farm income for a marginal farmer (those with less than one hectare land) to a meagre Rs 1 lakh, explains a senior official at the state’s agriculture department who did not want to be identified.

“Punjab should generate maximum jobs in the agriculture sector. But data show that in 2010, 15 per cent of total farmers in Punjab were marginal. In 2022, this figure dropped to 13 per cent. This implies that though land is getting divided and families are splitting, the young are leaving farming. It is no longer attractive for them,” says the official.

In a predominantly agrarian state like Punjab, the price of this slide and indifference is being paid by the youth. Disinterested in staying on in farming and ill-equipped to grab urban, high-paying jobs, they inhabit a liminal space of despair and political alienation.

“Abroad, they are ensured of a basic minimum wage. What they earn in a year in Punjab with two rounds of crops, they save that much money in a month abroad by doing odd jobs,” adds the official.

What will work

Successive governments in Punjab have failed to come up with a long-term vision to put the state back on growth track or improve the employability of youth. The interventions, experts say, will have to be multi-pronged. Farmers suggest a push to an agro-based industry at the rural level.

“We have the raw material. If we process it and sell it in the markets, we will make more profit. This will also start a stream of employment for the rural youth who do not want to do farming,” says farmer Jasbir Singh.

Industrialisation of agriculture will also benefit as it can provide the technical know-how and the machinery to operate on farms.

The 13-month-old Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) government in Punjab is seen to be breaking the ice with the industry, farmers, and educators. In the budget for 2023-24, it allocated Rs 13,888 crore for the agriculture and allied sectors—a 20 per cent jump from the previous year—and Rs 200 crore for the development of 117 schools. An agriculture policy is also in the making.

In February, a day before the 5th Progressive Punjab Investors’ Summit in Chandigarh, Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann held an informal meeting with a group of businesspersons to let ideas flow freely. The same month, he introduced the New Industrial and Business Development Policy 2022. In September last year, Mann had travelled to Germany to attend one of the world’s biggest trade fairs for the automotive industry held in Frankfurt and urged German and Polish companies to invest in Punjab. But the state’s debt burden of more than Rs 3 lakh crore may be an impediment, experts say.

Also Read: Ubalta Punjab: How top state fell to 16, rising to broken & why Punjabis are forever furious

Pockets of experiments

A handful of institutions in Punjab are trying to stop the brain drain by reviving interest in traditional career options like the National Defence Academy (NDA) and Union Public Service Commission (UPSC).

In Tarn Taran district’s Khadur Sahib village, a charitable trust Nishan-E-Sikhi is conducting coaching classes for UPSC, NDA and other professional courses like NEET and JEE, catering to about 40 undergraduate students from Ferozepur, Hoshiarpur, Gurdaspur, and Kapurthala.

“Not everyone in Punjab wants to go abroad. If we stay here and study hard, we can earn as much as our friends earning abroad,” says Gurnoor Kaur from Bham village, Gurdaspur.

With this year, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) has started its own drive to hand-hold students vying for a spot in government bureaucratic machinery.

It has opened Nishchay Academy and signed a contract with a private coaching institute in Chandigarh — Raj Malhotra’s IAS Study Group — and will cover food, lodging and coaching expenses of 25 Amritdhari Sikh students this year.

“The Sikh community felt that their representation in the UPSC was shrinking and they urged us to take an initiative to have more Sikhs in the government. In the 1970s and 1980s, many Sikhs were bureaucrats. These numbers have fallen since,” says Shahbaz Singh, assistant secretary, SGPC.

Lieutenant General HS Panag (retd) agrees that the attractiveness for bureaucracy, defence, and education-driven professions like medicine has faded in the state over decades.

“In the 1970s, my village Mahadian in Fatehgarh Sahib produced two doctors and five to six army officers. After 1975, it has not produced anyone who has got a job based on education,” he says.

Similarly, few men and women from Punjab qualify for Army jobs. The new recruitment policy of Agniveer was a big setback and discouraged youth from picking Army as a career option and undernourishment of Punjabi youth also disqualifies them, says Panag, who is otherwise a supporter of the scheme.

After it announced its UPSC initiative, the SGPC received more than 300 applications. Similarly, at Nishan-E-Sikhi’s classes, more than 70 students turned up for the entrance exam for UPSC coaching.

Operating in the same pool, an IAS coaching institute set up in 1998 by the Punjab University in Chandigarh claims that with good guidance, students can be driven to these professions.

“We get many Sikh students from rural areas of Punjab, and the number of students applying for the centre has increased over the years,” says Sonal Chawla, director of the institute.

But UPSC is a lottery. Students struggle to come up with a Plan B if they fail.

In 2016, Rankeerat Singh from Badala, a border town in Gurdaspur district, migrated to Canada for a business management course. Many youth from his region were going abroad to study, which his parents realised would be the best decision for him.

But after two years of hustling, Rankeerat came back to Punjab.

“Life abroad is very tough. You can’t just sit there like many youth do here. You have to constantly manage between your studies and work. If you can’t work, you cannot survive there,” he says.

For the past three years, he has been preparing to crack UPSC. But if he doesn’t make it, he sees no future for himself in Punjab.

“I will go back to Canada and do trucking work there. It is a better paying job than any work in Punjab.”