Chandigarh/Patiala/Ludhiana/Amritsar: Gleaming sarson ke khet (fields of mustard) as far as the eye can see — this was the image the name ‘Punjab’ evoked around three decades ago, partly thanks to Bollywood. A prosperous, industrious and joyful state, stepping out from the shadows of militancy.

Flash forward to 2022, and nearly everyone in Punjab is angry at the state of the economy. From farmers to government workers, they are out on the streets and protesting to show their growing resentment at Punjab’s downward spiral over the last few years.

It’s not hard to see where this is coming from.

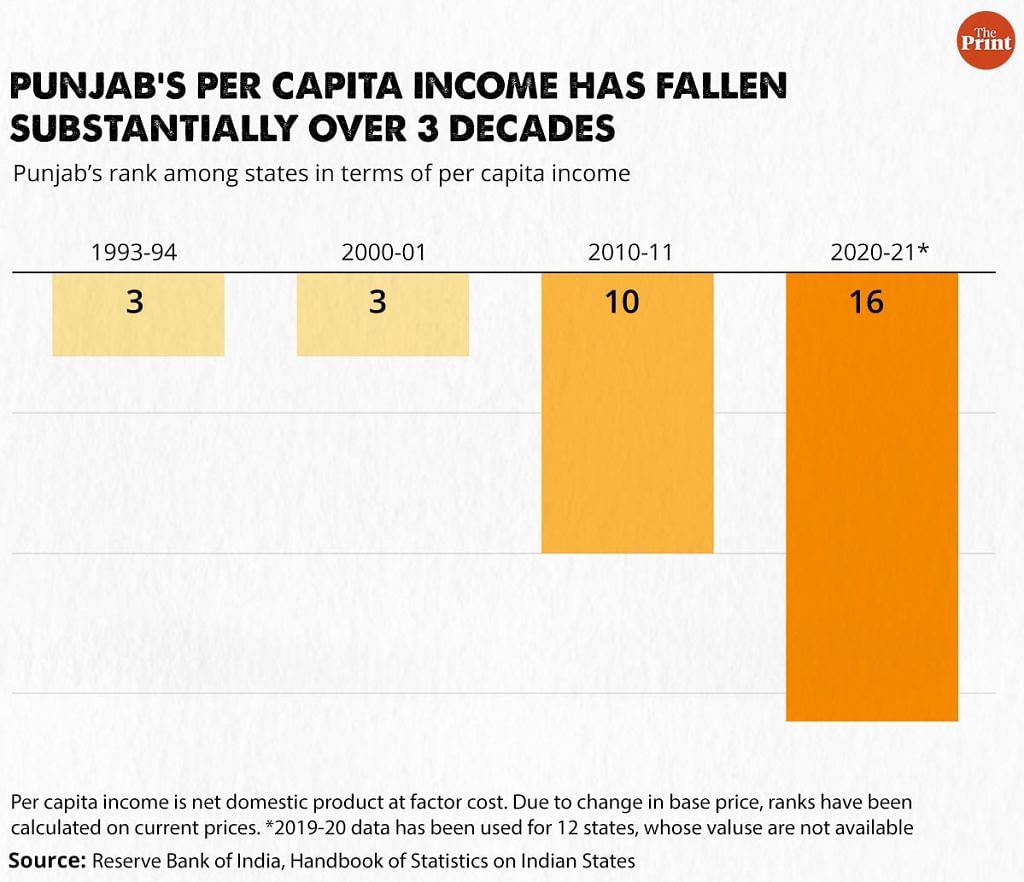

In 1993, a Punjabi on average earned the third-highest income among all the states (Union territories not counted, barring Delhi). Only small state Goa and Delhi performed better. Punjab retained this position until 2000-01. Since then, there has been an unrelenting slide.

By 2010-11, Punjab’s per capita income was lower than nine other states. Nearly a decade later, in 2020-21, there were 15 states with higher per capita income.

It’s not possible to calculate the precise growth of the per capita income due to changes in base prices (the denominator used for calculating growth). But the state rankings offer a peep into how other states outperformed Punjab on this growth metric.

Not just the per capita income, even the macro numbers around the agriculture, industrial and services sector are discouraging.

One would think that a high income base is likely to help the state to grow faster. But then why didn’t Punjab progress as it could have?

Ahead of the assembly polls this Sunday, ThePrint travelled through some of the state’s most important regions — the Union territory of Chandigarh, which serves as its capital, Patiala, Ludhiana, Jalandhar and Amritsar. And everywhere, the same sorry story was in full view — one of neglect, incompetence and political lethargy.

ThePrint visited Punjab’s departments of planning and employment generation to seek a comment on why the state’s economy hasn’t kept pace with expectations. However, both refused to comment until the Model Code of Conduct is lifted after the election results on 10 March.

Also read: All parties in Punjab talk ‘aam aadmi’, but field crorepatis — 93% for SAD, 91% Congress, 69% AAP

Agriculture shows stagnant growth

Much of Punjab’s economic prosperity came from rapid growth in agriculture. The five rivers in the state, from which Punjab derives its name, made the land fertile. The canals that were built after Independence only made farming more lucrative.

In the mid-1960s, Punjab was among the first states to modernise agriculture during the ‘Green Revolution’. However, the positive effects of this lasted only for a short while.

According to a study by Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, from 1971 to 1986, Punjab’s agriculture grew by 5.07 per cent on average even as Indian agriculture grew at a 2.31 per cent, that is, less than half.

In the following two decades (1986-2005), Punjab’s agriculture grew at 3 per cent, slightly higher than the national average of 2.94 per cent.

But between 2006 and 2014-15, Punjab’s agriculture story crashed. Its output grew by only 1.6 per cent in these years while India averaged 3.5 per cent.

Paucity of land made it difficult to have a sustainable source of growth. The state’s net sown area and irrigated area are nearly the same today as they were in 2004-05 — about 4.1 million hectares, according to Reserve Bank of India data.

Even so, the state still depends on agriculture, which contributes to about a quarter of its GDP of Rs 5.2 lakh crore. At the countrywide level, agriculture forms 17.6 per cent of India’s GDP (2018-19).

A state can’t grow more fields. But it could create more jobs and output outside the sector — by setting up industries. Has that worked in Punjab?

Also read: In post-Covid age of digital campaigns, parties spent just Rs 8 crore in 3 months on Facebook

Industries in neglect

In its glorious past, Punjab was known to take pride in its industries too, especially textiles, bicycle manufacturing and leather.

Looking over his multi-storeyed building, with a lawn and an auditorium, near Gill Chowk in Ludhiana, D.S. Chawla, president of United Cycle Parts Manufacturers Association (UCPMA), says “it all started with one tiny room”.

Chawla explains how small-scale industries drove Punjab’s economic growth.

“When they gave sops to small-scale industries, people opened up factories wherever they could. In the same tiny industrial unit, they would keep a bed and sleep after working throughout the day, which is why you find many residential buildings in industrial areas,” he says.

Despite facing instability due to the wounds of Partition in 1947, Punjab recovered fast.

According to an archive piece from the Economic and Political Weekly, the number of factories in the state swelled to 54,250 in 1955 from 2,311 in 1947, and was growing multi-dimensionally. The state became a fertile ground for hosiery, bicycles and their parts, handloom, sports goods and metal industry.

An erstwhile Planning Commission report from 2000 shows that by the 1980s, Punjab’s industry grew at an average of 21.75 per cent in 1980-85. Despite facing years of militancy, the sector grew by 10.75 per cent in the next five years.

However, after the Indian economy was liberalised in 1991, the industry growth stalled at only at 1.87 per cent (1992-97). This slowed down further to 0.98 per cent (1998-00), the commission report said.

Between 2015-16 and 2020-21, the industry witnessed only 6.78 per cent annual average growth, according to the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII).

“The first thing that Punjab had to do was to promote free markets and competition, through which the private sector would grow, offer well paying jobs. But the politicians themselves became industrialists and marred competition in the state. Investors feared spending in Punjab due to this,” says Lakhwinder Singh Gill, professor emeritus at Punjabi University’s Khalsa college in Patiala.

This political takeover of industries in Punjab has been documented.

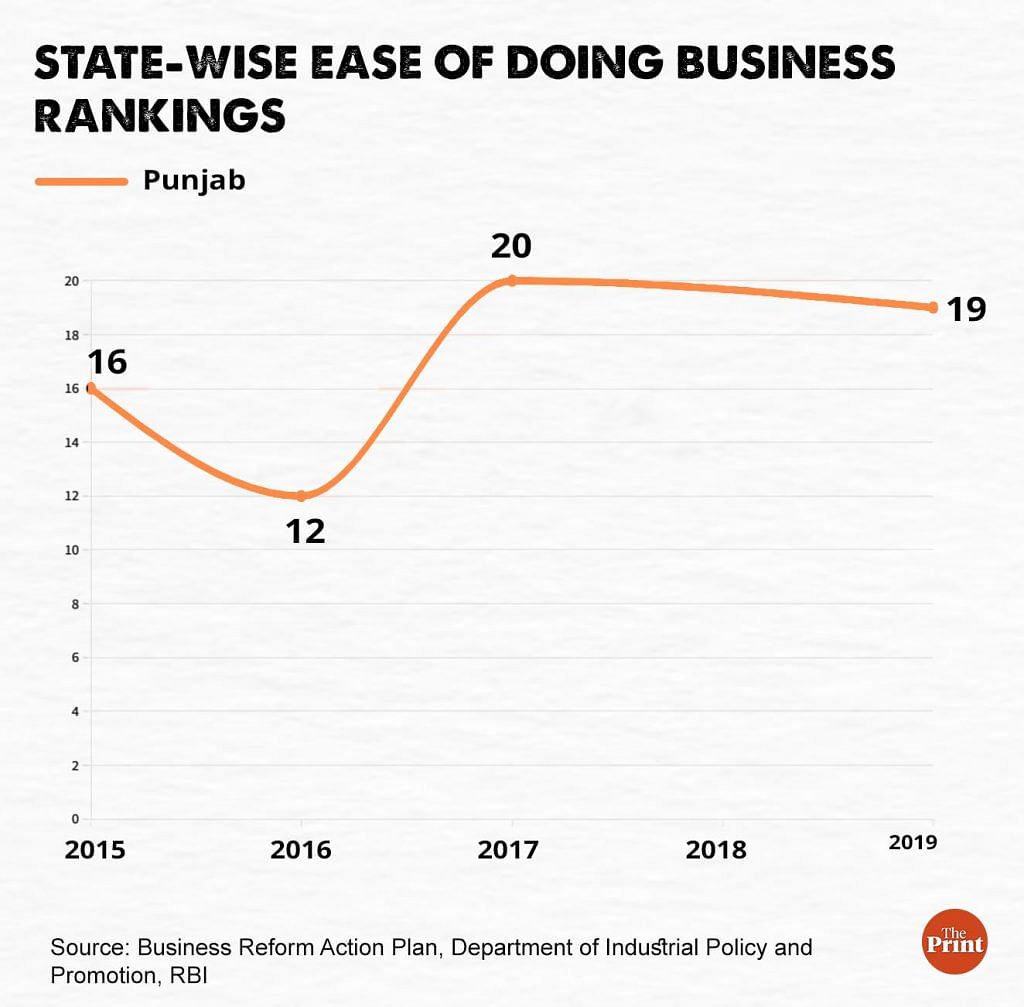

Consequently, Punjab also ranks in the bottom 10 for its ease of doing business.

According to the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion’s ease of doing business rankings, Punjab fell from 16 in 2015 to 20 in 2017. In the latest rankings (2019), it improved marginally to get to 19, but placed itself in the bottom 10.

While other states offer better incentives to industries and promote competition, even the companies that are working in Punjab plan to move out, industrialists tell ThePrint.

In early 2000s, when neighbour Himachal Pradesh offered tax sops to incentivise industries in its town Baddi, which borders Punjab, the pharma industry fled the state.

Cheap availability of land and other incentives caused an exodus of the textile industry in the decade that followed. And now the bicycle industry, which manufactures 90 per cent of India’s bicycles, is also considering moving out of the state.

Like Ludhiana’s charred grey skies carrying industrial smog and roadside dust, the future of many industries doesn’t look pretty either.

Thanks to Covid-induced demand, the cycle industry is witnessing another resurgence, but industrialists say their neglect by the Punjab government is making them think about moving out of the state.

Chawla says the industrialists left in Punjab are being offered lucrative options by other states. “All politicians come with promises, take our money and forget about us. Our demands for competitive pricing of input goods and reduction of ‘inspector raj’ are still the same as they were 20 years ago,” Chawla says.

“Today, running an industry in Punjab doesn’t offer much since it is not a consuming state. Other state governments are offering us lucrative incentives like 50 per cent purchase if we set up our factories there. If our neglect continues in Punjab, we might have to opt out,” he warns.

The state of labour doesn’t look much different either.

Asked about staffing in their respective factories, labourers say 90 per cent are migrant workers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Shankar, a factory worker who has worked in Punjab for over 20 years, doesn’t call the state his home. “I am a voter in Uttar Pradesh. The day my state starts offering me jobs according to my skill even for Rs 2,000 less than what I earn here, I will leave,” he says emotionally.

Shankar and his pals live adjacent to the towers emitting black smoke. “It’s still the same as it was two decades ago, except that inflation pinches the meagre earnings more now,” says Shankar, who earns just about Rs 10,000 a month.

Chawla admits that Punjab’s people are not interested in doing low-paying industrial jobs, which is why the industry relies on migrant workers, but the charm of Punjab giving them the best wage has eroded.

Also read: ‘Kaale angrez, fake Kejriwal’ — gloves off as Channi & Delhi CM bid to be Punjab’s real aam aadmi

Non-existent service sector

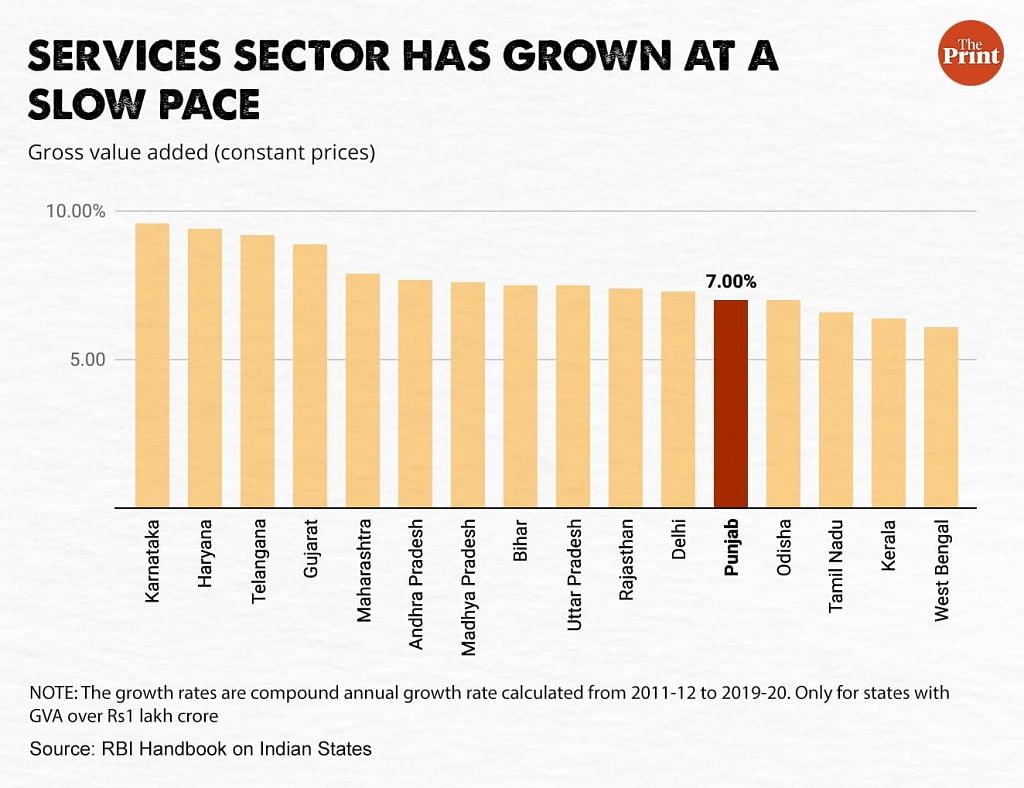

In the last 10-15 years, India has witnessed a significant jump in the information and technology sector. But Punjab has managed to stay largely untouched by this.

If the services sector’s growth is considered in states where it is worth at least Rs 1 lakh crore (gross value added in 2019-20), Punjab grew at an average annual rate of 7 per cent between 2004-05 and 2019-20. This is low and places the state in 12th position among 16 states ThePrint analysed.

Its neighbour Haryana has done much better in this regard with an average growth rate of 9.4 per cent per annum, second only to Karnataka that has grown by 9.6 per cent.

This is all too visible in Punjab as the tall glassy buildings that line the streets in Bengaluru, Gurugram and Hyderabad are missing.

Though it has managed to build an IT park in Mohali, bordering the state capital Chandigarh, and the works to build Amritsar into an IT city are also almost complete, lower salaries are keeping the youngsters both dissatisfied and away from Punjab.

In 2018, the state finance minister had reportedly said that “it is better to be paid low than sit idle”, when questions of low salary offered to engineers were posed to him.

The other service avenue was inland trade with Pakistan, which used to give employment to thousands. But even that opportunity has been snatched after the 2019 Pulwama terror attack.

Since then, India has raised import duties on trade with Pakistan to 200 per cent and hasn’t looked back since. According to data from think-tank Bureau of Research on Industry and Economic Fundamentals, the trade ban hit at least 9,000 families or 50,000 people in Punjab, with almost no hopes in sight about its revival.

However, despite the economy in tears, the state has resorted to populist policies by promising freebies and making almost no fundamental changes to the existing structure of its economic development, believes Lakhwinder Singh Gill.

“The economy of Punjab will not come back on track until the state government doesn’t let the private sector grow freely. The government has to remove the fears of industrialists and provide space for more jobs to grow. And it needs to re-think its remuneration policies to retain hard-working people back in Punjab,” Gill adds.

Punjab government sources tell ThePrint that the state’s high land costs have kept the industrialists away, as they get cheaper viable options in other states such as Madhya Pradesh. They also said the state’s poor finances aren’t judiciously utilised, so the option of providing high-paying government jobs is ruled out.

“They are not generating revenues, but offer thousands of crores in freebies. Where will the money to pay decent salaries to young skilled workers come from? These people have Canada-level expectations,” said a source.

(Edited by Amit Upadhyaya)

Also read: Voters in 3 seats next to Chandigarh have same concern: Concrete jungle & host of civic issues