Patiala/Jalandhar: Completing higher secondary education usually means going to college or joining a vocational course, but for many youngsters in Punjab, it means signing up for coaching classes to learn English.

In Kartarpur, a small town about 20 kilometres north of Jalandhar, droves of fresh-out-of-school students sign up for seats in institutions that offer preparatory courses for the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) exam. Passing it is essential for those who aspire to study or work abroad, and in Kartarpur, that’s just about every other young person. This city, along with Jalandhar, falls in Punjab’s Doaba region, also known as the NRI belt — where getting out of India is the biggest dream.

In these cities, it’s hard to escape hoardings emblazoned with the advertisements for IELTS coaching, or shiny buildings tempting students with the flags of Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

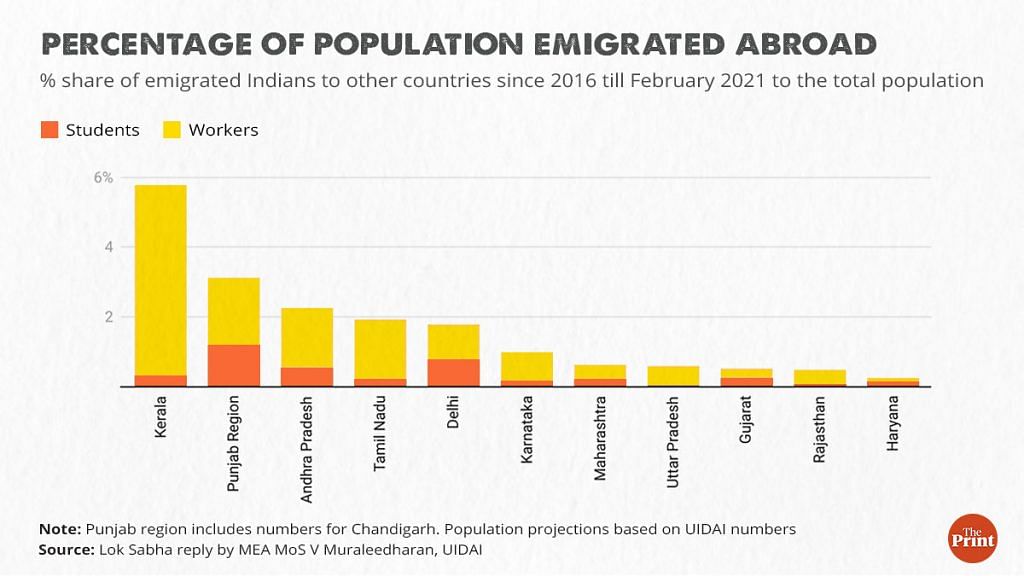

Between 2016 and February 2021, about 9.84 lakh people moved to other countries from Punjab and Chandigarh (including 3.79 lakh students and over 6 lakh workers), according to a Lok Sabha reply from V. Muraleedharan, Minister of State for External Affairs.

These numbers, when compared with the 2020 population projection for Punjab and Chandigarh, show that 3 per cent or 1-in-33 Punjabis moved abroad in the last five years or so.

While a greater percentage — 6 per cent — of Kerala’s population moved abroad in the same time period, what sets Punjab apart is the proportion of students who leave to pursue an education and to also put down new roots.

In Punjab, nearly 38 per cent of those who immigrated did so on student visas, while in Kerala, this category was just 5 per cent of the immigration from the state.

There’s another difference too.

Much of Kerala’s migration is directed to the Middle East or Gulf countries, which do not grant permanent residence or citizenship. In many cases, therefore, the immigration is temporary and families stay back home.

In Punjab, however, there are reports of entire villages going empty and people selling off their lands, suggesting that those who leave do not intend to return.

Apart from a paucity of job opportunities in the state, students in Punjab seem to be victims of the lack of quality education. Furthermore, experts believe that unless systemic problems are addressed in Punjab, the exodus could add to the woes of the state.

Also Read: Malwa, Majha, Doaba: Divided by rivers, each Punjab region has distinct political identity

It’s all about English-Vinglish

At Matt’s Institute of English Language in Kartarpur, almost every student ThePrint spoke to wanted to settle down in Canada. Many of the pupils here live in nearby villages and struggle with English, but seem confident and hopeful about their prospects abroad.

Taranjeet Kaur, 18, recently finished school in the commerce stream, and aspires to become a “successful businesswoman” once she makes her way out. “In Punjab, it is difficult to find opportunities. The ones that exist don’t pay well,” she says.

Sammohit, who is also 18, also has a clear plan: “Study, get a job, and take PR (Permanent Residency)”. He’s aware that he might need to take up a part-time job to support himself while he studies abroad, but is more than willing to do so.

“There are no opportunities in Punjab right now. I am fond of cooking, so I can work as a part-time cook and earn a decent amount while studying… something that’s impossible here,” he said. A similar job in India would earn only Rs 10,000 to 12,000 a month, he added, and the hours would likely be much longer too.

When ThePrint asked the youngsters at the institute if there was anything that might convince them to stay on in India, most had the same answer: “Give us opportunities that pay well.”

However, many of these students are not well-prepared to study abroad because they struggle with basic English.

According to Monita Dhingra, the administrative director of the coaching institute, most students have very weak foundational knowledge of English.

“Children from humble families, including those who were taught in government schools, are learning the basics of English in IELTS coaching centres. Their foundations in school aren’t that strong, which makes it difficult to attain a desirable IELTS score,” Dhingra says, adding that the IELTS business has expanded by “at least 10 times” over the past decade.

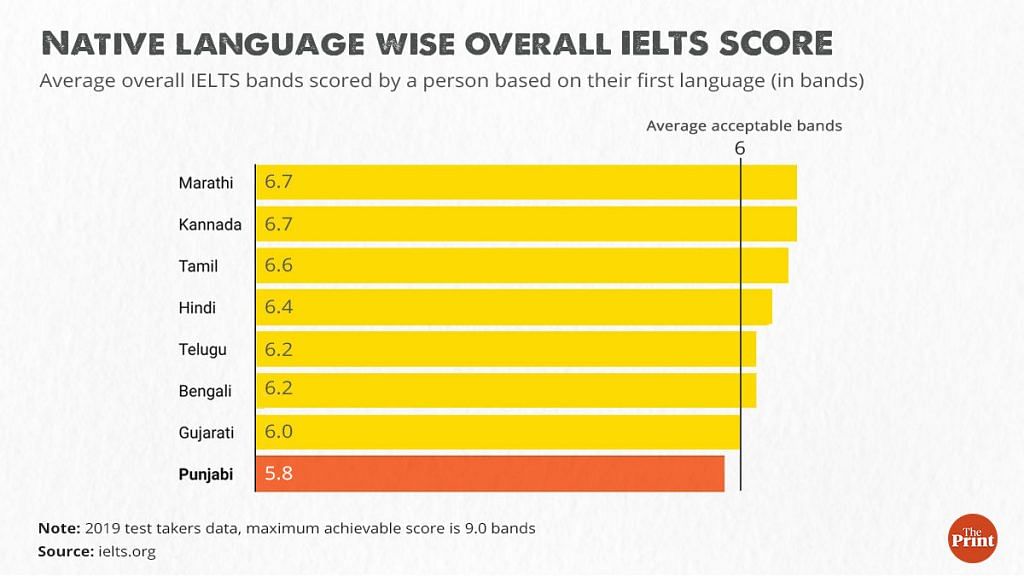

Indeed, figures made public by IELTS of the mean scores of students based on their first-language background reveal that Punjabi-speakers scored lowest among the Indian regional languages. The overall average band score of a Punjabi test-taker (under the academic category) was 5.8. For context, this score was 6.7 for Marathi and Kannada-speakers, 6.6 for Tamil, 6.4 for Hindi, 6.2 for Telugu and Bengali, and 6.0 for Gujarati. Most universities abroad require a minimum band score of 6.0 (the maximum band score one can attain is 9.0)

In 2021-22, Punjab dedicated 12 per cent of its budget to education, ranking it at 26 among 29 states and union territories for which data was provided in a PRS report published in November last year.

There are also indications that government schools in the state do not provide a very high quality of education. For instance, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) for data from 2018 showed that among Class 1 children in government schools, only 58 per cent could read letters and 67 per cent could recognise numbers. In contrast, the corresponding figures for Class 1 students in private schools were 83 per cent and 94 per cent respectively.

Punjab’s performance in NITI Aayog’s Sustainable Development Index has also been patchy in the quality education parameter. In 2019, its rank had jumped to 7 from 14 in 2018, but in 2020, it slipped to 11 with a score of 60 — the lowest in three years of assessment.

Also Read: Why self-congratulatory balle-balle culture, not Pakistani drones, is biggest threat to Punjab

‘Have to stay away from family for a dignified job’

The economy of Punjab, which was once celebrated as the wealthiest state in India, has been stagnating for many years, across all sectors — agricultural, industrial, and services.

There aren’t very many jobs, and even the government of Punjab is stingy with new recruits, paying them only the basic salary — which means no house rent allowance or other benefits — for a probation period that lasts three years. Practices like this can have a snowball effect.

“What this does is that it creates a price ceiling. If the government offers low salaries, the private sector follows suit or might even pay less. This is keeping the initial salaries low… consequently, the educated skilled workers seek jobs where they are paid more,” says Lakhwinder Singh Gill, professor emeritus at the economics department of Punjabi University’s Khalsa College in Patiala.

Even students who are pursuing their higher education in Punjab don’t believe they can thrive in the state.

Sitting in the lawns of Punjabi University in Patiala, students chit-chat about their classes and friends, but ask them about their future, and the mood darkens.

Harjinder Singh, 23, is studying for his master’s degree in psychology. He believes that the state is in grave need of mental health experts because of pervasive drug abuse, but he is now considering seeking employment elsewhere because “the pay is so low”.

Harjinder’s friend Lovepreet Singh joins the group a little later. Lovepreet studied at the private Chitkara University in Rajpur near Patiala, but currently works in design and animation in Mumbai.

“I remember 80-90 per cent of my friends had to either go to Noida or Bengaluru or Mumbai. Punjab didn’t have any jobs for us. It has some now, but too underpaid. I have to stay away from my family for a dignified job,” Lovepreet says.

Women in Punjab have it even tougher since they are often denied the freedom to move to other parts of India, explains Manpreet Kaur, who is studying for her MA in psychology.

“The female students in some families have to think twice before stepping out to study… often, they end up getting married and have no career of their own. My parents will allow me, but not all parents do that,” she says.

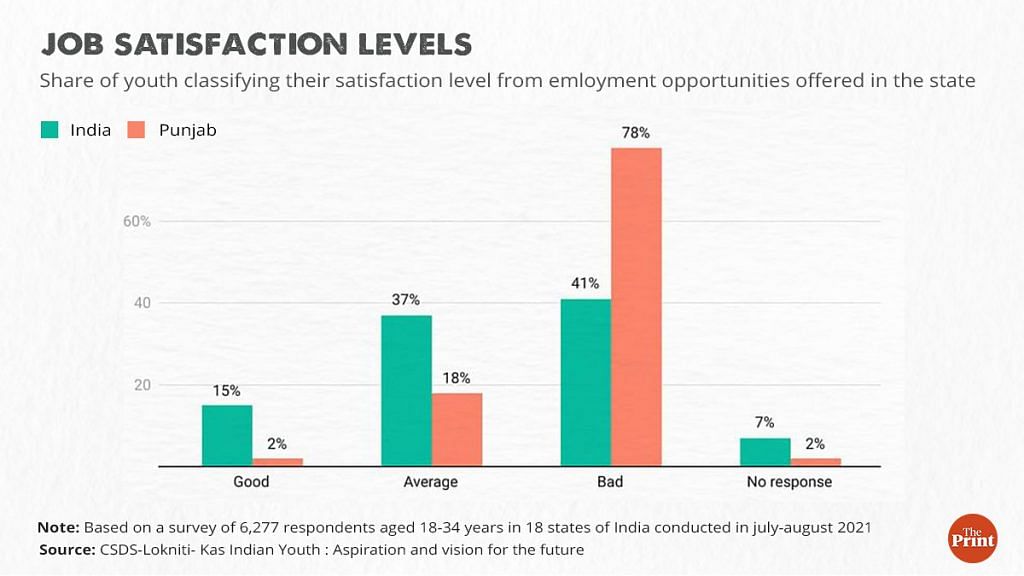

The concerns of students are in line with the findings of a survey conducted last year by the Centre for Studying Developing Societies (CSDS), which found that 78 per cent of respondents in Punjab felt the state had ‘bad’ jobs compared to the national average of 41 per cent.

Also Read: Ubalta Punjab: How top state fell to 16, rising to broken & why Punjabis are forever furious

A problem that most politicians don’t address

The exodus of youth from Punjab has entered the state’s political discourse ahead of the polls, but surprisingly, there seems to be very little will to retain young blood. Instead, most political parties are promising to offer benefits that will facilitate the exit of students.

The Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD), for instance, promised last year that if it came to power, it would issue “student education cards” with interest-free loans for Rs 10 lakh for not just college fees but IELTS coaching.

A Student Education Card with an Interest Free Loan up to Rs 10 lakhs to be issued to the students for the purpose of college fees, coaching fees like IELTS, and will cover educational institutions in foreign countries also.#SochTarakkiDi @officeofssbadal pic.twitter.com/vjJgtt6mtc

— Shiromani Akali Dal (@Akali_Dal_) August 3, 2021

Last month, the Congress government in Punjab signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the University of Cambridge Press India, through which it could provide IELTS coaching to about 40,000 youngsters studying in the state government’s Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) and polytechnic universities.

During the function for signing this MoU, state Minister of Technical Education Rana Gurjit Singh extolled the “hard work and entrepreneurship” of the Punjabi diaspora and said that the state government had set up a foreign study and placement cell to “facilitate the migration of youth through legal pathways to foreign countries through a very robust system of District Bureaus of Employment and Enterprise (DBEEs),” according to an Indian Express report.

The Aam Aadmi Party, however, has taken a different approach. Bhagwant Mann, the party’s president in Punjab, said last month that its agenda included stopping the “migration of money and talent” by creating more job opportunities in the state.

According to Paramjit Singh, who teaches political economy at Panjab University, Chandigarh, mass migration from the state could cause grave problems for Punjab and increase the gaps between the rich and poor.

“It takes money to move abroad, so those who have resources are able to do it. Mostly it’s the upper middle class which can afford it. Some of them are selling their lands, which will go only to the rich. What it might do in the long run is that it will empty the middle class in Punjab, and the gaps between the rich and the poor will just widen,” he says.

When NRIs return for holidays in Punjab, it can also fill those who are left behind with an even greater desire to follow in their footsteps. “When NRIs visit their villages, they throw lavish parties and exhibit their prowess, which gives false hope to those who are staying here,” says Ramesh Chander, a retired Indian Foreign Services officer who lives in Jalandhar.

Chander is convinced that Punjab will eventually see a “brain gain” — a return of successful members of the diaspora.

However, when ThePrint asked students if they would ever come back, a few said they might want to invest in Punjab after becoming successful, but most were quiet.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Fund my studies, I’ll get you to Canada — Now Punjabi men are being abandoned by NRI wives