New Delhi: What’s common between Parkash Singh Badal, Captain Amarinder Singh and Charanjit Singh Channi, apart from the fact that they have all been Punjab chief ministers?

They are all from Punjab’s Malwa belt.

And do you know why Doaba, separated from Malwa by a river, is electorally significant even though it accounts for just about 23 of the state’s 117 assembly seats?

While we are at it, to the west of Doaba lies Majha, where voting has generally been known to follow a distinct pattern. Any guesses what it is?

As we all learnt in geography back in school, Punjab literally translates to ‘Panj’ (five) and ‘Aab’ (sources of water), and is known as the ‘land of five rivers’ — the Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum.

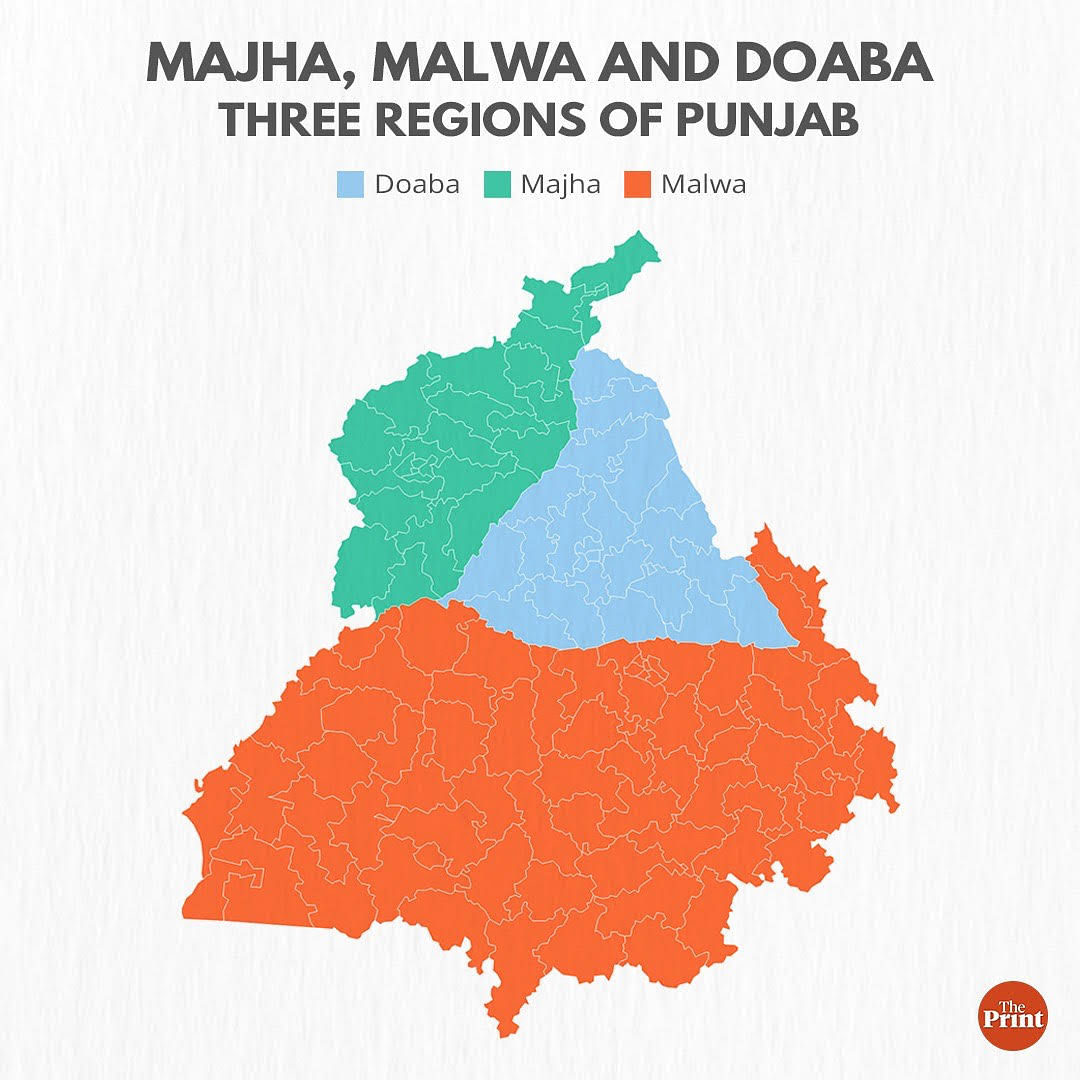

To truly understand its politics, however, one must delve deeper into the significance of the state’s three key regions — Majha, Malwa and Doaba — broadly carved by three of these rivers, with their own distinct social, economic and political identities.

Going from west to east, the Majha region of present-day Punjab falls between the Ravi and the Beas. Then begins Doaba, the land between two rivers (do aab), which starts from the Beas and goes on till the Sutlej. Beyond the Sutlej lies the Malwa region.

In the 20 February Punjab assembly elections, each region will play a crucial role according to its individual identity.

While Malwa was at the helm of the farmers’ movement, it is also is known as the zamindari belt as it’s home to rich farmers and landholders, but is infamous for farmer suicides.

Majha, the Sikh ‘panthic’ (religious) belt, has several ancient gurdwaras and a very religious population, an important factor in elections, while Doaba is the epicentre of Dalit politics, and is also known as the ‘NRI belt’ of Punjab.

Also Read: Channi & Sidhu patched up, but Punjab Congress now facing leaders’ squabbles in Doaba & Majha

Malwa, the land of zamindars and activism

Malwa is the largest region of Punjab, both geographically and politically. Nearly 58 per cent of the state’s assembly seats (69 out of 117) fall within this region. A hotbed of politics, it is also home to the state’s largest and most populous city, Ludhiana.

The region’s sway over Punjab politics is evident from the fact that 83 per cent of the state’s chief ministers elected since 1966 (when Punjab was reorganised and Haryana became a separate state) have hailed from here, including present CM Charanjit Singh Channi, who is from Chamkaur Sahib — a sub-divisional town in Punjab’s Rupnagar district — which is part of Malwa.

Channi’s predecessor Captain Amarinder Singh, who left the Congress last year after he had to step down as CM and formed his own new party Punjab Lok Congress, belongs to Patiala. Before him, the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) headed by the Badal family ruled the roost for 19 (non-consecutive) years under the chief ministership of Parkash Singh Badal, their stronghold being the Bathinda Lok Sabha seat.

In the last few years, Malwa has also become a land of change, where new entrants perform well in the political arena. In 2017, Arvind Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) had won 18 seats in the region, which is significant because the party had won only two in Doaba and none in the Majha region.

Comedian-turned-politician Bhagwant Mann, AAP’s chief ministerial candidate for the upcoming polls, hails from Sangrur, which was the region’s second largest district (after Ludhiana) until Malerkotla was carved out last May.

As the AAP gained ground in Malwa, the Akali Dal’s performance here declined.

In 2012, the Akalis had registered a historic win over Punjab as they were re-elected, a rare phenomenon as the state swings every poll. “By 2012, the panthic politics in the state had declined. Simultaneously, the Akali Dal had worked on the state’s roads, police reforms and economic development, which gave them power once again,” Prof. Ronki Ram, who teaches political science at Chandigarh’s Panjab University, told ThePrint.

“However, in 2017, the Akalis were wrong in their perception that the religious leaders would help them out, since economic development had become a stronger factor than religion in Punjab’s electoral outcomes,” he added.

According to Prof. Ram, there are three broad reasons why the Akalis repeated a term in 2012: “Firstly, they brought governance reforms, opened Suvidha Kendras and put provisions of penalising the police for not taking action in time. This eased delivery of public services and brought great relief to people dealing with the paperwork. Second, they meticulously expanded the road network in Punjab, and lastly, they made Punjab a power surplus state, electricity cuts became shorter — all these factors led to their historic win.”

Another reason why the region has a strong influence over the state’s politics is the dominance of the zamindari class. The existence of rich landlords plays a key role here, where the average landholding is higher than that in the other two regions, which leaves scope for richer candidates.

According to a paper by professors R.S. Ghuman, Inderjeet Singh and Lakhwinder Singh of Punjabi University, Patiala, the share of farmers with more than 10 acres of land here was about 27.5 per cent, with Doaba having 23 per cent such farmers and Majha 17 per cent.

“Having large lands has benefited the Malwa region, making it the zamindari belt of Punjab. The farmers here are rich and consequently, as elections have become dearer, financial power has been equated to political power. As a result, it’s no surprise that most chief ministers have come from this region,” Lakhwinder Singh, professor emeritus at Punjabi University, told ThePrint.

He added that with large farmlands and incomes, Malwa, compared to Majha and Doaba, also has a less educated population. Despite being a large region, it only has one big city, Ludhiana, which is located far from most other parts of the region, resulting in fewer opportunities for the people.

“One also has to realise that the region also has a huge number of small and marginal farmers, many of whom, due to slow economic growth and inability to move to other industries, have died by suicide. Malwa is also the farmers’ suicide belt of Punjab,” Lakhwinder Singh said.

A joint study by Punjabi University, Ludhiana’s Punjab Agricultural University and Amritsar’s Guru Nanak Dev University (GNDU) had revealed that owing to financial pressures post 1990, more than 97 per cent of Punjab’s farmer suicides were reported in the Malwa region.

Malwa also took centre stage during the year-long farmer movement over the central government’s recently repealed farm laws. According to a study conducted by professors Lakhwinder Singh and Baldev Singh Shergill of Punjabi University, around 80 per cent of the farmers who died during the protests belonged to the Malwa region. The study went on to state that “on an average, a deceased farmer cultivated 2.94 acres of land”.

The reason why it is the belt of the protesting farmers has to do with the region’s history and the activism that has prevailed here for a long time, explained Lakhwinder Singh.

“Soon after India attained independence, the PEPSU-Muzara movement that ran for decades became successful in granting land ownership rights to landless tenants (tillers of the soil). The fight was fought with Leftist ideology, and hence, it has a significant impact on the people from this region. Which is why people in this region are influenced by Leftist ideology and tend to participate in revolts,” he added.

Lakhwinder further said the concentration of the farmer outfit Bhartiya Kisan Union (Ugrahan) in the Malwa region could also explain its active participation in the farm protests.

“The BKU’s Ugrahan group is mainly concentrated in the Malwa region. The group connects farmers via meetings and has been fighting for their rights for a very long time. This non-political group would visit every single village and connect farmers via membership. Their long struggle and fight for farmers rights is the reason why so many people united in the farmers protest,” he added.

Also read: Majha votes, Punjab follows? Not just Sidhu vs Majithia, here’s why all eyes are on this region

Majha, where religion and politics intertwine

Electorally, Majha has 25 assembly seats, making it the second-most influential region, a long way behind Malwa in terms of numbers.

It is also known as the ‘panthic’ belt of the state. ‘Panth’, in Punjabi, means path, and in a religious sense, the ‘Guru’s way’. Due to the historic importance and prevalence of ancient gurdwaras, the Majha region is also known as the birthplace of early Sikhism.

Amritsar, Pathankot, Gurdaspur and Tarn Taran districts fall within this region. Majha is home to the Golden Temple in Amritsar and the Kartarpur Corridor that connects the state to Gurdwara Darbar Sahib in Pakistan, both important places of worship for the Sikh community.

The average landholding in Majha is small, according to the paper by Punjabi University professors — over 58 per cent farmers here own less than five acres of land.

“Earlier, the jathedari system had both religion and politics intertwined. However, it was more prevalent in the Majha and Doaba regions,” Prof. Lakhwinder Singh said.

The jathedari system, he explained, was the one in which the gurdwara or the religious leaders (jathedar) would decide which candidate people in that region would support, and hence, money didn’t matter much at an individual level.

“But all that’s gone now. With the dilution of jathedari, the zamindars caught up with the politics in the region, which has seen a big rise in mafia raj one encounters in the state today,” Lakhwinder Singh added.

Another distinct feature of Majha is that elections here tend to get uni-directional, which means that unlike Malwa and Doaba, the people of Majha broadly support one party during an election, which changes every time (2012 being an exception).

In the last election, the Congress had won 88 per cent of the seats in the region, and 63 per cent in 2002. In 2012, the Akali Dal had won 46 per cent seats (exception), 61 per cent in 2007, and around 67 per cent in 1997.

But Prof. Ronki Ram believes that this might not be the case in the upcoming elections.

“About 18-20 per cent of the votes in Majha, are the votes of change. However, this time, a major chunk of these change votes might go to the Sanyukt Samaj Morcha (SSM), the farmers’ body fighting election. Of course, the change also means that some will root for the AAP, but many believe that people might opt for local options as AAP is still believed to be an outsider party,” he told ThePrint.

Also read: Majha votes, Punjab follows? Not just Sidhu vs Majithia, here’s why all eyes are on this region

Doaba and its Dalit votebank

Doaba is the smallest region in Punjab politically, with 23 assembly seats. Nonetheless, the region is important in terms of Dalit votes.

Flanked by the Sutlej and Beas, Doaba, where the irrigation system reaped the benefits of the Green Revolution, is known to have the most fertile land.

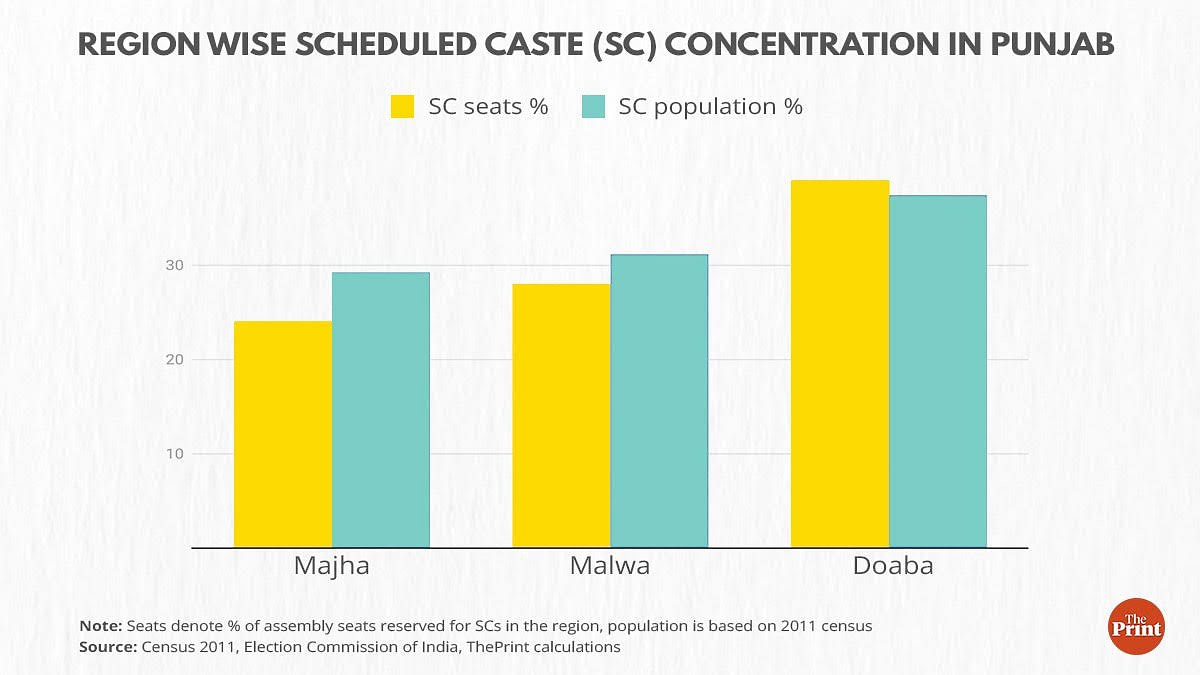

According to the 2011 census, Scheduled Castes (SCs) form around 32 per cent of Punjab’s population, the highest in the country. However, compared to Majha (29.3 per cent) and Malwa (31.3 per cent), Doaba has the highest proportion of Dalits (37.4 per cent).

This makes Doaba the epicentre of Dalit politics in Punjab. Around 40 per cent seats in the region are reserved for Dalits, compared to 27 per cent in Malwa and 24 per cent in Majha, according to an analysis of Election Commission data.

The Akali Dal is contesting this election in alliance with Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) to get its caste equation right.

This region is also known as the ‘NRI belt’ of Punjab. Though it has a high share of small and marginal farmers, the share of educated people is reportedly also higher in this region compared to Majha and Malwa.

The trend of migrating to developed countries started from Doaba. “Doaba has historical linkage with foreign countries and was the first region of Punjab from where people left to settle in other parts of the world. Post the militancy, youth from all parts of Punjab started migrating abroad, but this trend sharpened in the last two decades due to slow growth of Punjab’s economy and persistence of high unemployment rates,” Lakhwinder Singh said.

Small landholdings in the Doaba region also came with smaller economic gains, hence it became a good incentive to search for well-paying jobs.

“Due to the small landholding size, people started working hard to get jobs. Consequently, more and more people invested in better education. You will find a lot of Arya Samaji schools and colleges in this area. This belt is also the education hub of Punjab,” Prof. Ronki Ram told ThePrint.

Another important factor, according to Prof. Ram, is that Doaba is the birthplace of the Dalit Renaissance: “Doaba is the birthplace of the Ad-Dharm movement, which started in the 1920s. The Dalit community lobbied to be recognised as a separate religion, and by 1931, there were about five lakh people recognised as Ad-Dharmis and they are categorised as Scheduled Castes in India.”

“These people are the followers of Guru Ravi Das and formed Ravi Das deras (religious centres) not just for spiritual reasons, but also for building their social capital. The Dalits of Majha and Malwa take encouragement from the Dalits in Doaba,” he added.

Since the 1969 Punjab assembly polls, with the exception of 2012, state governments have changed every election. Sometimes, Doaba and Malwa have moved in different directions, but the broad trend is that nobody sticks in Punjab for longer than a term, irrespective of region.

(Edited by Gitanjali Das)

Also Read: Punjab’s Dalits are shifting state politics, flocking churches, singing Chamar pride