Jhaloor (Sangrur): Gurdev Kaur, an elderly paralysed woman, was lying in a pool of blood after a Jatt mob chopped off her leg. They didn’t stop at that; standing on the roof of her house, they emptied the overhead tank on her while she lay on her charpai. The force of water pushed her to the ground, and flooded the angan, drowning her. The Mazhabi Sikhs of the village Jhaloor watched on helplessly — the Jatts wouldn’t let anyone near her.

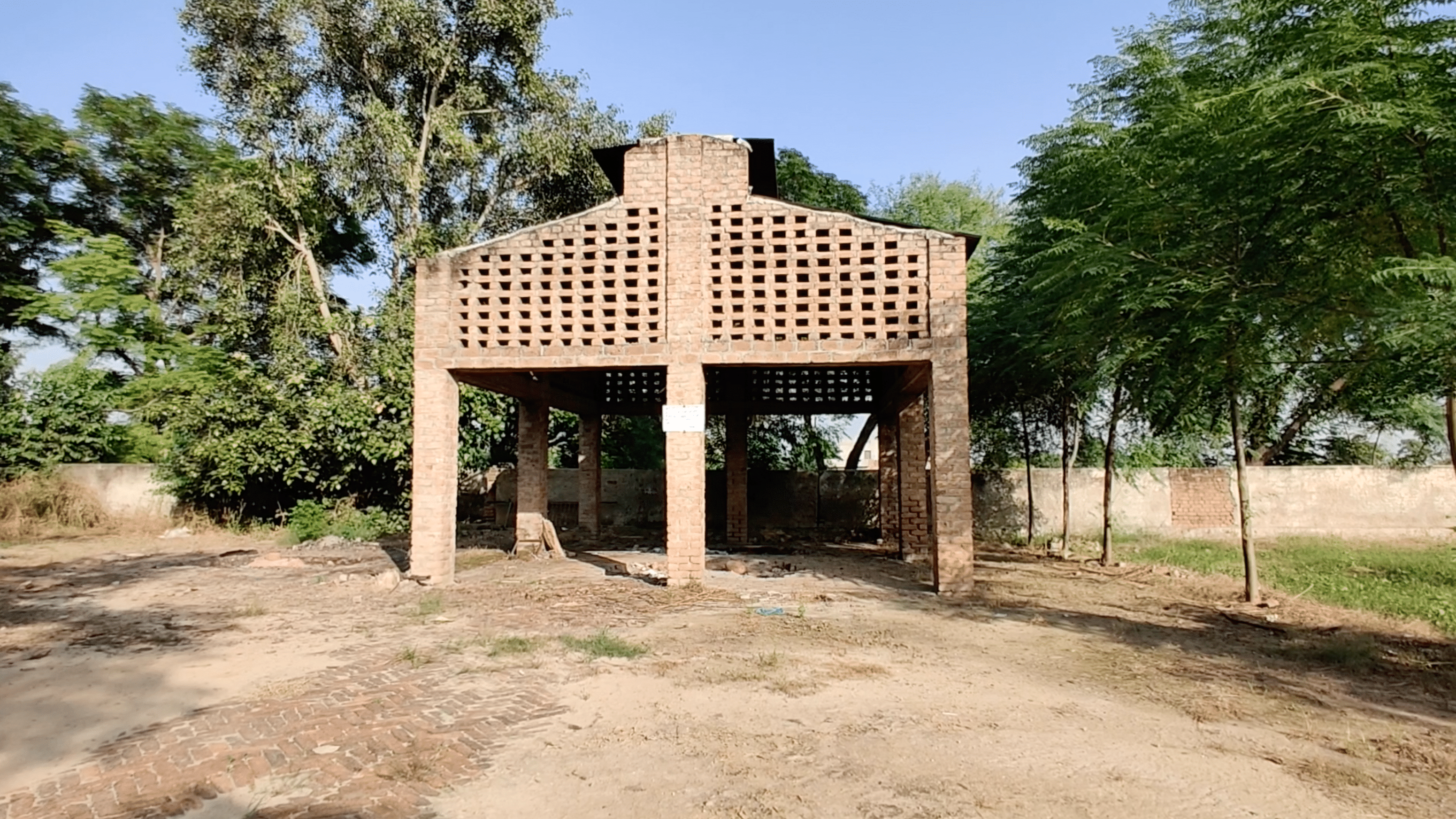

That was on 5 October 2016 and it was all over a piece of land. Today, she is a martyr with a memorial and a library in her name in the middle of Jhaloor.

Five years later, the horrific lynching of a Dalit Sikh near Delhi, allegedly by the Nihangs, is creating another firestorm in Punjab. The Nihangs, police say, suspected the Dalit of desecrating the Sarbloh Granth (considered to be work of Guru Gobind Singh), a claim yet to be established. In the gory act that took place at the Singhu border — the epicenter of protests against the three farm laws passed by the Narendra Modi government — the man’s hand was chopped off before he was killed and his body tied to a barricade.

Jatts of Jhaloor in Punjab’s Sangrur district had cornered the Dalits of the village, who had been agitating to claim their right on one-third of the panchayat land, reserved for the community under the Punjab Village Common Lands (Regulation) Act 1961. But it was the Jatts who exercised control over the land through proxies.

Kaur died on 12 November 2016 in a hospital but her last rites were held on 27 November. Her body had been preserved so that the labourers from other neighbouring villages could gather to pay their respect. Hundreds had gathered, with numerous kafilas of men and women flooding Jhaloor. Kaur was then wrapped in a red cloth and offered to the great Sutlej — perhaps, the labourers could not afford the fire to turn into ashes, for they wanted it to burn forever.

Also read: How faraway Lakhimpur Kheri is reshaping Punjab politics as Congress, AAP, SAD look to cash in

The changing political reality

Today, Punjab is witnessing an increase in Dalit representation in politics. All of a sudden, political parties are wooing the demographic they haven’t tried to butter up in the past. The state with about 32 per cent Scheduled Caste population got its first Dalit chief minister in Charanjit Singh Channi in September this year. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has promised a Dalit CM if voted to power, while the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) has reserved the post of the deputy CM for a Dalit leader. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), the political newcomer in Punjab, too has a Dalit face playing a key role — Leader of Opposition Harpal Singh Cheema.

Not just political high offices, Dalits in Punjab today are also occupying prominent positions in religious organisational structures. Giani Harpreet Singh, the current head priest of Akal Takht, the highest temporal seat in Sikhism, hails from the Dalit community.

But for the Dalits of Jhaloor, the struggle doesn’t stop at mere representation. They are unmoved by the appointment of Channi as CM. “So what we have a Dalit chief minister now, those in the administration are still upper castes, and won’t do anything in our benefit. The Chief Minister can’t micromanage everything,” says Balbeer Singh, son of Gurdev Kaur.

Balbeer says he’s associated with the Zameen Prapti Sangharsh Committee, a movement though which he is helping other villages realise their land rights, to honour his mother.

Various movements have led to a Dalit upward social mobility in Punjab that has empowered the community to start talking emancipation from the oppressive systems dominated by upper castes. Stories of small movements in a village spark similar demands and campaigns in other parts of the state. Kaur’s death has made Jhaloor the ground zero of the uprising for land rights, as it has become one of the few villages in Punjab where the SC community successfully bids for and cultivates the reserved panchayat land.

This assertion of Dalit identity is visible in statues of Babasaheb Ambedkar at chowks and his iconography on almost every house. It is sparkling in palace-like houses in the villages of Doaba, felt in the hymns of their religious movements, loud and clear in Chamar pride songs. It’s a complex story that has been brewing in the land of Kanshi Ram for over a couple of decades, buoyed also, in part, by the awareness and upward mobility that Punjab’s NRIs remitted back to residents. Channi’s appointment is perhaps a delayed nod to Scheduled Castes of Punjab saying — like it or not, we’re here, and won’t be the silent and silenced majority anymore.

But why are political parties, all of a sudden, announcing Dalit chief minister candidates, and wooing the SC voter when they have always courted the socially, politically and economically powerful Jatts?

According to Member of Parliament from Amritsar, Gurjeet Singh Aujla, it all started after the BJP, taken aback by the Kisan Andolan led by Jatt Sikhs, made a call for having a Dalit CM in Punjab. This was followed by Akali Dal’s announcement of reserving the post of the deputy CM for a Dalit. “BJP always looks to bank upon casteist or communal votes. It practices the politics of hate. So now, everyone is all about Dalits. There’s no casteism in Sikhism, you can come see the langar,” he says. “Look at the qualifications of Mr Channi… he was made CM because he’s well-educated, kind and a good worker. He wasn’t a surprise pick per se since he has also served as Congress’ leader of opposition,” Aujla adds.

Also read: Modi can’t behave as if ‘sab changa si’ and not speak up on Lakhimpur Kheri

Migration and social dignity earned

Moving abroad has brought the SC community of Punjab economic prosperity, social dignity and afforded them positions of power in local politics, especially to the Chamars of Doaba. Take, for example, the story of Madan from village Talhan, Jalandhar district.

Till about two decades ago, Madan used to work as a labourer in the fields of landowners in his village. Now in his early 40s, Madan’s tanned face and worn off fingernails stand testimony to his past. He talks proudly about his greatest possession — two tractors. “There was a time I used to till someone else’s land on my foot, pulling bulls through the might of my waist, nurturing their soil through my own blood and sweat. And today, I own two tractors and hire labourers to work on land that I own,” he says.

From living in a kutcha house to having a cemented roof on his head, Madan’s life has seen a 360 degree turn — “From an extremely poor family with little to eat and no social standing, we’ve become a success story. Also, do you know I’m a member of the panchayat here? Do you know as a mazdoor, I couldn’t have possibly thought I’ll become a member of the panchayat one day?”

Various international Ambedkarite institutions have also helped give financial assistance to disadvantaged people who have the potential but lack the means of going abroad. 92-year-old L.R. Balley, founder of Ambedkar Bhavan in Jalandhar and pioneer of Ambedkar Mission in the state says: “Ambedkarites have worked a lot abroad. I’ll give you three examples: they’ve made Ambedkar centre in Southall, England; in Birmingham, they established Budh Vihar, Ambedkar Bhavan and library, and an Ambedkar museum. NRIs have contributed a lot in social movements, health, education of the chamar community back home, and helped other members move abroad to achieve a better life.”

Also read: ‘He didn’t go out alone, only had Rs 100’: Lynched Sikh’s kin in Punjab find Singhu trip ‘fishy’

Religious assertion

With their newfound prosperity and language of assertion, comes hard questions about faith – much like the African-American churches in the United States. The golden dome towering the skyline of an average village is a gurdwara meant for all its residents. But that’s only in theory. It most likely belongs to the upper castes of the village. At the doors of Nanak, who rejected the Varna system in his Gurbani, casteism is still rampant.

Most villages in the state have three-four Gurdwaras belonging to the Ravidassias or the Mazhabis or other sections of the SC community. The contrast between upper caste and lower caste gurdwaras is more stark in the villages of Majha and Malwa. These villages have bigger, sprawling grand gurdwaras belong to the Jatt Sikhs. In stark contrast are humble one-room Bhai Jeevan Singh Gurdwaras or Valmiki temples that look like in need of urgent repair — meant for the Valmikis and Mazhabis.

The way upper and lower caste people leave the world is very different too.

At village Haryaou in Patiala district, the Jatts have three-acre land to cremate their dead, and the way to the crematoria is decorated with beds of roses, three Mazhabis working relentlessly to maintain it. The crematorium of the SCs doesn’t even have a motorable road, is full of dead tree carcasses, and stinks of dead rats with dogs scavenging about.

After Channi became the CM of Punjab, Facebook was full of casteist slurs targeting him. But, according to Aujla, those remarks aren’t organic because “there’s no casteism in Sikhism and those Facebook comments aren’t the ground reality. Go to villages, see there’s no restriction or anything in Gurdwaras.”

The lynching of the 35-year-old man at Singhu border, for allegedly desecrating a holy scripture, tells a different story of the social fault lines, divorced from the claims Aujla makes.

Residents of Jhaloor, Harayou and Narli also allege degrees of untouchability that they face in gurdwaras. The villagers allege that they’re not allowed to take home Guru Granth Sahib if there’s a celebration or death in the house. If a Dalit kid unknowingly steps into a gurdwara run by the upper castes, he’s often given prasad in a separate utensil, which is washed immediately. After any celebration in the village, the upper caste members have the first claim on langar, and the food reaches the plate of a Dalit only after the zamindars have eaten to their heart, they say.

The upper castes, and indeed some among the Dalit community, insist casteism is a thing of the past: “See, there’s no casteism in Sikhism. All that is rubbish. Didn’t you see how hard Sikhs worked during lockdown? We didn’t ask anyone about their caste before giving them Guru ka langar. Then why would we deny the same to the poor of our very own villages,” asks Gujinder Singh, a Jatt resident of Dingrian village in Adampur district. “There are three gurdwaras in the village but it’s not like we don’t go to the Ravidassia Gurdwara or prevent them from going to the other one. These are community spaces and belong to everyone,” he says.

But then what explains more and more people wanting to break away from Hinduism and Sikhism? In 2010, Ravidassias announced they’re a separate religion at Kashi, the birthplace of Sant Ravidas, a demand they reiterated in 2020.

The SC community is also attracted to Deras such as Dera Sacha Sauda, Radha Soami Satsang Beas and the Nirankaris, and hundreds of other Deras in Punjab. Many are also converting to Christianity.

The Deras carry political heft and influence voters. Political parties are always on their toes, wooing the saints of these cult organisations. Dera Sach Khand Ballan, considered the seat of the Ravidassias, is among the strongest. Earlier this year, when the current head Niranjan Dass fell sick, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had promptly called to check on him. After becoming Chief Minister, Channi, a Ramdasia Sikh, went straight to Dera Sacha Ballan after visiting the Golden Temple. He has also promised to set up a chair for Guru Ravidas at a 101-acre site.

At Dera Ballan, ThePrint spoke to a volunteer who didn’t wish to reveal his name. He says: “dekho ji there’s no equality in Sikhism, sab bekaar ki baatein hain. I find peace and tranquility here. Guruji here has embraced me, given me dignity. I dedicate my life to him. But it’s nonsense to say Guruji tells us who to vote for.”

But some voters are skeptical. “People belonging to one dera usually are unified in who they vote for. Sure, they’re not told explicitly what to do, but there’s enough propaganda,” says Balwinderjit, sarpanch of village Talhan in Jalandhar.

Also read: ‘He was running with a Sikh holy book’: The ‘crime’ for which Sikh man was lynched & hacked

Conversion to Christianity

In Majha and Malwa regions, SCs are converting to Christianity in great numbers. It’s easy to meet someone named Mandeep Kaur or Kuldeep Singh with a rosary around their neck. They’ve stopped changing their names after converting, fearing of persecution.

In Tarn Taran, a pastor tells ThePrint that about 27-28 Protestant churches have come up in the last 5-7 years in the district. A catholic priest says there are eight big Catholic churches in the district while he has lost count of how many there are in villages.

Neither of the two came on record because of a palpable fear of persecution by Right-wing elements, miffed with missionaries over conversions. When ThePrint went to interview a pastor in Tarn Taran, his aides didn’t allow it. Despite us producing our press cards, visiting cards, and showing them our YouTube videos to establish our authenticity as journalists, they weren’t convinced and accused us of being BJP workers trying to profile them.

But conversion isn’t proving to be beneficial after all.

“People who convert lose the benefit of getting reservation. So now, a lot of them aren’t changing their names so that they can avail the benefits of not just being aChristian, such as access to quality education, but also of reservations as Scheduled Castes,” says chairman of National Scheduled Castes Alliance, Paramjit Singh Kainth.

Sikhs, as well as the Hindus, are uneasy with this mass migration out of the respective religions. They have started their own missions to enable ‘ghar wapsi‘. We met volunteers of one such effort in Amritsar’s Preet Bazaar — members of the Vishwa Satsang Sabha. In Preet Bazaar itself, they’re running four make-shift schools and dharamshalas where kids are taught about Sikh and Hindu religions, tutored, and given snacks. They run similar ‘ghar wapsi‘ programmes in Ludhiana, Patiala, Jalandhar and New Delhi.

Bhupinder Kaur, a teacher and member of the Vishwa Satsang Sabha, says: “We never fully embraced the lower castes in our religion. Had we paid attention to their small needs, taken care of them, they wouldn’t have taken to Christianity. If we become part of their happiness and sadness, and include them, then only we’ll be able to do something.” Pritpal Singh, another volunteer chimes in: “As far as casteism goes, Christians practice caste too and have separate churches like for Catholics and Protestants. So are they treated equally there?” he asks.

In Punjab’s Gurdaspur, Christians form an important vote bank, comprising nearly 20 per cent voters of the Lok Sabha constituency—the jurisdiction with the highest minority population in the state.

Prominent Christian leaders in Punjab include Sonu Jafar, president of the Christians Front and a prominent face in the Majha region of the state. He quit Congress to join AAP earlier this year.

Akal Takht head priest Giani Harpreet Singh says that ‘Christian missionaries are running a campaign of forced conversions’ in the border state. The Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) has dispatched 150 teams of preachers to Punjab’s villages to stop such conversions and is running a campaign called ‘Ghar Ghar Andar Dharamsaal’, where they teach children about Sikhism.

The SGPC is also running the ‘Ik Nagri, Ik Gurdwara’ campaign, but it seems to have failed terribly on ground.

ThePrint tried contacting SGPC President Bibi Kaur at her office, via her PA and left calls and messages on her personal number but there was no response.

Also read: Channi in Punjab to Gond in UP — An English nursery rhyme explains their sudden elevation

Chamar pride pop culture

Chamar pride songs are all the rage today – Ginni Mahi’s Danger chamar, Babbar Sher Chamar by Rimpy Grewal, Proud to be Chamar by Babbu Chander. But let’s go back to where it all started from.

The year was 1986 when a fairly popular desh bhakti singer Roop Lal Dhir, son of a labourer from village Gadhi Ajit Singh in Nawanshahr district, got inspired by Kanshiram and Ambedkar, and decided to record a cassette of nine songs — five on Saint Ravidass and four on Ambedkar. Back then, nobody was willing to record songs praising the Dalit icons, much less ones that carried lyrics critical of Gandhi. Dhir and his colleague Sartaj recorded the songs with their own money — Rs 2,000 — and somehow managed to get them to stores.

Shortly after the release, death threats to him, and rape threats for his daughter and wife overwhelmed the singer. But that didn’t deter Dhir’s spirits who only grew from strength to strength. He took his music abroad and performed in Australia, Canada, United States and Italy. His fans gifted him an Alto car in the 90s and Dhir became the first Dalit in his village to own a car. “I would often receive calls where the person using the choicest abuses, and often they all had the same thing to say — ‘tum choodhe chamar, tumhari itni himmat ki humari jaisi gadiyon mein baithoge (How dare you low born use the same cars as ours?)”.

From being a son of a labourer who had to stop school for months because he didn’t have money to buy a uniform, to now being a popstar with gadi, bangla and bank balance, Dhir’s life has taken a 360 degree turn. “I’m happy my songs have become lokgeets among the chamar community now. But I can’t forget the time I used to sit with my brothers, empty stomach, and wait for papa to come from the zamindar’s house and bring us his leftovers for roti,” says Dhir.

Today, young people from the chamar community sing songs of social revolution and change with gumption, and have a nationwide appeal — gathering millions of views on YouTube. In their songs, they express their anger and assert the Chamar identity aggressively. Sample this lyric by Babbu Chander:

Rkhde dunaliyan noon load karke

Firde aa putt maut noon vyaan noon

Chamaran de putt poori rkhde ain thukk

Jigra chaahida saanoo hathh pan noon

(We, the sons of Chamars are so gutsy that it needs courage to confront us. We keep our arms always loaded and always eager to embrace death.)

Also read: What Jat and Dalit Sikhs say about Congress’ Punjab move and next CM: Survey

Exclusionary movements

In his songs, Dhir searches for Be-gumpura — a world without any pain, any discrimination that has been mentioned in the writings of Saint Ravidas. “Zaliman ne zulma di att kitti mitron. Rajbag lain layi maidan vich nitro. Be-gumpure da, Begumpure da, Be-gumpure da panth kede vele vich sajna, ji hun bhi na jage toh phir kato jagna. O jaago, jaagan da Vela,” sings Dhir in a recent composition, loosely translated as: ‘the oppressor has reached the limits of oppression. It’s time for us to realise Be-gumpura, if you don’t come and stand for Be-gumpura now, when will you?’

But the utopia of Be-gumpura seems to have no place for the Valmikis and Mazhabis.

The songs gaining popularity from the SC community are Chamar pride songs not Dalit pride songs. Dhir says he is working to change it. Kuldeep, a Mazhabi from Jhaloor village, who’s currently studying music, says the lack of money is the reason that is preventing renaissance from reaching his community. He says: “Mazhabis are not coming to the fore to produce music because they lack economic capital. You need Rs 35,000 to make a music video. In Doaba region, the Chamar community has the financial backing of NRIs. Mazhabis are barely able to afford education, let alone a music video,” he says.

Also read: Punjab’s many Dalit Sikhs – Ramdasia, Ravidasia, Mazhabis, Ranghretas, Rai, Sansi

The borderlands

Perhaps nobody is more alien to the concept of a revolution among Punjab’s Dalits than the Valmikis and Mazhabis of the state’s border areas, who are living as destitute, enduring centuries of exploitation with no respite whatsoever.

No cylinders, no toilets, not even a cemented roof — the Mazhabis and Valmikis in Tarn Taran’s Narli village, roughly 300 metres from the Pakistan border, sleep under the stars, no matter how cold or hot it gets. Most houses are kutcha, and some don’t even have electricity. Unemployed, a lot of men fall victim to the business of smuggling drugs coming from Pakistan, also often of drug abuse, says social activist Paramjit Kaur who has worked in the border belt.

“Women are vulnerable to sexual exploitation at the hands of zamindars, if they go to relieve themselves in the field or work in their houses. The saying in villages is — use an SC woman as ‘practice’ before you actually get married. They’re exploited when they go out to relieve themselves in the field, are especially vulnerable if they work at zamindars houses” says another social activist, who requests anonymity for the fear of persecution at the hands of Jatts.

The villagers here have no access to resources. Children mostly are unable to go to school. “The depot holder says the government doesn’t send the wheat but I think Jatts don’t consider us part of the pind, so he holds it back. He doesn’t give us anything. I haven’t received grain in 15 years. All zamindars get the wheat, no benefit transferred by the government reaches us,” says Palwinder Kaur, 30, a farm labourer in Narli Village. Another labourer alleges zamindars holding the grain back. “I say give us the address of the place where the kanak is being held back. And we’ll go there and get sadda haq. Our wheat is going to the zamindars,” says 32-year-old Bhuta Singh.

When ThePrint spoke to Devendra Singh, depot holder of Narli, he said he can’t do anything about it. “The sarkaar gives older wheat rotting in warehouses for free consumption. “How is it my fault if it’s inedible?” he says, adding, “nobody is poor in our village. Look at these Dalits, they have motorbikes and cars and live in decent houses but they still want free stuff.”

The labourers also hold a negative perception of the farmer protests at Delhi borders that have been going on for almost a year. “Nobody talks about labourers’ issues there. We are never given the stage there, they limit our interaction with the media. The Kisan-Mazdoor Ekta is only on paper. Not that we welcome companies, but also it’s not like farmers are kind to us,” says a member of the Punjab Kisan Union, who has also visited the Singhu border.

Also read: Yogi expands his Cabinet, but still keeps SC/STs away from real power

The difference in upward mobility

The Chamar community, who consider themselves above the Mazhabi and Valmiki castes in the social ladder, have historically worked in the leather industry, are considered relatively well-read, and have been part of historical movements.

Harish Mahey, grandson of Seth Sunderlal, one of the founding members of the Ad-Dharm movement, tells us that the community worked majorly as workers for Muslims, or ran much smaller businesses in the pre-Partition era. Post partition, worker Chamars took over the flourishing businesses of those Muslims who left for Pakistan. “After Partition, when traders left their businesses and went to Pakistan, the quantum of work was transferred to the Chamar community. After the Second World War, there was especially high demand for leather. It was a prosperous time, and a good opportunity for the people here to earn good money. Till 70s, the business was in good form,” says Mahey.

Boota Mandi is still regarded as the ground zero of various social movements that have led to the upliftment of Chamars since.

The Chamars are also concentrated in Punjab’s Doaba, the more prosperous region that has seen social movements like Ad Dharm, and Ravidassia and Ambedkarite struggles. Shaeed Bhagat Singh and Kanshiram belonged to this region. Here, people are more politically aware and recite Ambedkar’s teachings by heart. And Ambedkar can be found everywhere — in temples, gurdwaras, living rooms, study rooms, libraries, in the names of streets, and in statues on chowks. Such is not the case in Malwa and Majha regions.

“It’s important to remember that the SC community isn’t a homogeneous group. There are caste divisions within caste lines. The Weaver community consider themselves one step above the Mazhabis. Punjab is unable to move forward because nobody is moving forward in unity,” says Professor Ronki Ram of Punjab University.

The appointment of Channi, though seen with skepticism, has been welcomed by the Bahujan samaj, who are happy that someone from ‘their biradari’ now occupies the highest office in the state. That he has made a flurry of announcements for the benefit of the SCs is an added benefit — his promises on loan waivers, lower water bills, and subsidised power, in his constituency Chamkaur Sahib may please the SC vote bank.

But on ground, many, like the villagers of Narli, still wait for their share of food, water and electricity. And the longer they wait, the more they’ll be convinced that even a CM from their own community couldn’t bring the change that has been promised for decades.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)