New Delhi: India is rejoicing its second straight year of above-normal monsoon, a first in six decades, but in a quiet corner of the Haripar village in Gujarat’s Rajkot, a 75-year-old farmer is finding it hard to cheer.

Laljibhai Bhura’s groundnut farm is rotting away after suffering severe damages due to excess moisture. Bhura fears his entire crop will fail quality checks, ruling out any government procurement.

“The burden of a failed crop now weighs heavy on my shoulders,” he says, pointing out that the lockdown ruled out any additional sources of income that he earned through ferrying people across villages on his tractor.

While Bhura and many in his village deal with a failed groundnut crop, 70-year-old Kanuri Hira from Chaygaon in Assam is struggling to sell her earthen pots. There has hardly been any order since the lockdown was imposed in March to contain the Covid-19 pandemic.

As winter approaches, the septuagenarian is worrying about not having warm clothes and enough food.

“We used to live by selling earthenware. During lockdown, we could not fetch the mud we need to make pottery, and even if we make some, where would we sell those? Since the first lockdown, we have been having a tough time. We cannot even afford two meals a day,” says Hira.

The womenfolk of Assam’s native Hira community make earthenware using special ‘Hiramati’ clay and ancient techniques. These traditional women potters of Tari Gaon village, situated 44 km from the state capital Guwahati, have now lost their only source of livelihood.

In Uttar Pradesh’s Sheikhupur village, Basheer Ahmed is facing a similar quandary. Like others around him, he makes elaborate zari lehengas that are sold in Delhi and Hyderabad and remain in high demand during the wedding season.

“Until last year, we used to have night shifts and worked 15-16 hours a day for six days a week. Now it has reduced to four days and hardly six hours of work,” says Ahmed, as four workers sit beside him on a cot, patiently weaving sequins and golden thread on a piece of cloth.

A zari lehenga takes about three weeks to prepare and sells for around Rs 30,000-40,000. The upcoming wedding season is a ray of hope for Ahmed but business is yet to pick up pace.

“Bik jaaye to naseeb (will be lucky if it sells),” he says.

Also read: How Modi govt’s farm reform laws could help turn India into ‘a food-export powerhouse’

The strain on rural economy

In the first quarter of 2020-21, the Indian economy shrunk 23.9 per cent, after two months of lockdown to contain the pandemic adversely hit manufacturing and services. Agriculture was the only sector that registered a positive growth of 3.4 per cent. And many economists and experts were of the opinion that India’s rural economy would be the lone shining star, or the silver lining to the cloud of general economic doom.

But that was not to be.

The bumper harvest notwithstanding, India’s rural economy is struggling to stay afloat amid multiple challenges of falling incomes, spread of Covid and rising unemployment due to a sharp increase in the return of migrants from urban areas.

Logistical challenges thrown up by the pandemic in selling their produce and wares means that many are having to contend with substantially lower prices adversely impacting their income levels.

The Narendra Modi government’s interventions to support the rural sector — not large in scale — were front-loaded and have now run their course. The various support measures for the agri-rural economy including cash transfers and free foodgrains have either ended or are due to in the next couple of months.

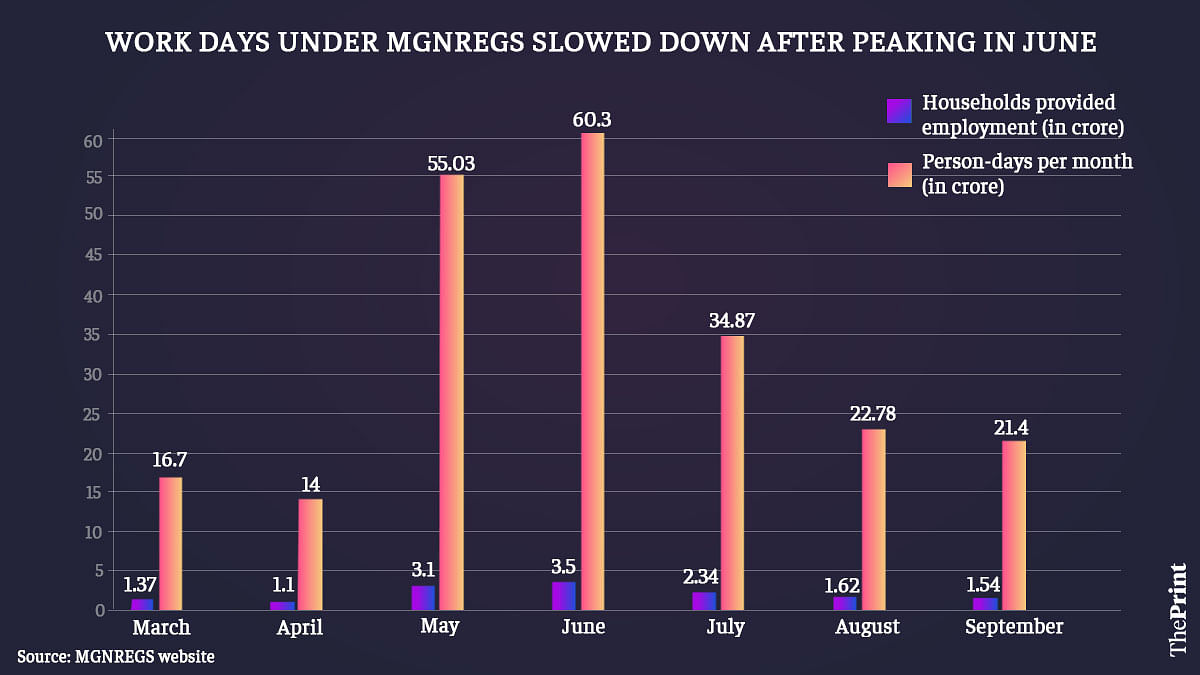

The higher budget allocations under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) have also been utilised to a large extent and this is reflected in the falling person-days under the scheme. The increase in the minimum support prices (MSP) announced by the government is also negligible and unlikely to have a major impact on farmer incomes.

On the state of the rural economy, Himanshu, associate professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, says, “None of the indicators are pointing to the rural economy bouncing back. Most of the indicators are down. Prices of many commodities have fallen indicating falling demand. That is also an indicator that incomes are not increasing in rural areas.”

He says the trajectory of Covid has also shifted to the rural areas and all the accompanying problems associated with the pandemic will now shift there.

“The government front-loaded its cash transfers but in terms of actual money, the amount was insignificant,” he notes.

What could also adversely impact rural incomes and activity in the coming months is that rural areas are increasingly accounting for most of the new Covid cases being reported.

The months of July and August saw a sharp surge in cases in rural districts. This trend moderated in September, said an 8 October State Bank of India research report. But it pointed out that of the 25 worst affected districts in September, 14 were rural. The report also pointed out that these rural districts have large numbers of mandis that could mean agri supply could be impacted.

The government, however, is of the view that it has taken several measures to address rural distress.

Kailash Choudhary, Minister of State for Agriculture, stresses the Modi government is continuously increasing its spending in the rural sector.

“The thrust of the Atmanirbhar Bharat package is the rural sector. The prime minister in his 15 August speech has also announced measures for agriculture. There is no question of ignoring the rural economy. Covid has impacted a few sectors but we have taken several measures to end that distress,” he says.

Earlier, the Ministry of Finance had also pointed out how rural demand is gaining traction.

“The implementation of Aatmanirbhar Bharat (AB) package and unlocking of the economy have ensured that economic recovery in India has gained momentum. This is seen in agriculture with production of kharif foodgrains in 2020-21 estimated to go past the previous year’s level,” the ministry said in its monthly economic outlook for September released on 4 October.

“The growth of demand in the rural sector is reflected in registration of two wheelers/three wheelers/passenger vehicles along with tractor sales reaching/surpassing previous year levels in August,” it added.

Also read: Best time to invest in India is now, banker Uday Kotak says as he lists 5 ‘right sectors’

MGNREGA provides reprieve, but running out of funds

For the current fiscal, the government provided an additional Rs 40,000 crore to the rural job guarantee scheme, taking the total allocation to Rs 1 lakh crore. This allowed many to find work and sustain their livelihoods in the rural areas.

In Punjab’s Chunni Kalan village, Kulwinder Kaur, 47, found work through NREGS, which helped manage her household after both her husband and father-in-law were without jobs for months. “Earlier, my husband and father-in-law were managing the house expenditure but because of coronavirus, both of them didn’t have any work for four months,” she says.

While the situation has improved and the two now have work, she continues to work under the scheme to bring additional income to the house as more food is being consumed, with her children spending more time at home due to shut schools.

Chandrayya used to work as a watchman in Hyderabad’s Alwal area before the 66-year-old lost his job during the lockdown and returned to his village Kondapak in Telengana’s Medak district with his wife and two minor daughters. His wife Yadamma, 55, also used to work as a domestic help and faced months of no work.

Both of them are now relying on daily wage and NREGS jobs to survive in the village. They do not plan to go back to Hyderabad over fears of the virus’s spread in cities more than villages.

Neeraj Kumar was also laid off from a garment factory in March. The 25-year-old returned to his village Kastali Vaishya in UP’s Aligarh. During the lockdown, he worked under the NREGS and earned somewhere around Rs 5,000. “However, the work is irregular,” he says.

With many migrants returning to their villages and seeking work under the scheme, a substantial part of the scheme’s budget has now been exhausted.

Data from the official NREGS website shows that after peaking in June, the number of households that were provided with work as well as the person-days per month under the scheme fell over the next three months.

In June, 3.5 crore households were provided work under the scheme but this fell to 2.34 crore in July, 1.62 crore in August and to 1.54 crore in September. In terms of person-days per month, from a peak of 60.03 crore in June, it fell to 21.4 crore in September. This has also led to a fall in rural wages and income.

“Notwithstanding the additional allocation, MGNREGA funds have been utilised to quite an extent. Most of the state governments have already spent the money with many people moving to rural areas from urban areas,” Himanshu says.

Also read: RBI’s truce with bond market at risk as Modi govt ramps up borrowing

Sharp fall in rural incomes

Average wages for people in rural areas have fallen in the last few weeks, with the drop in person-days employment.

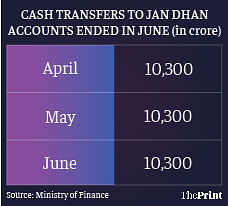

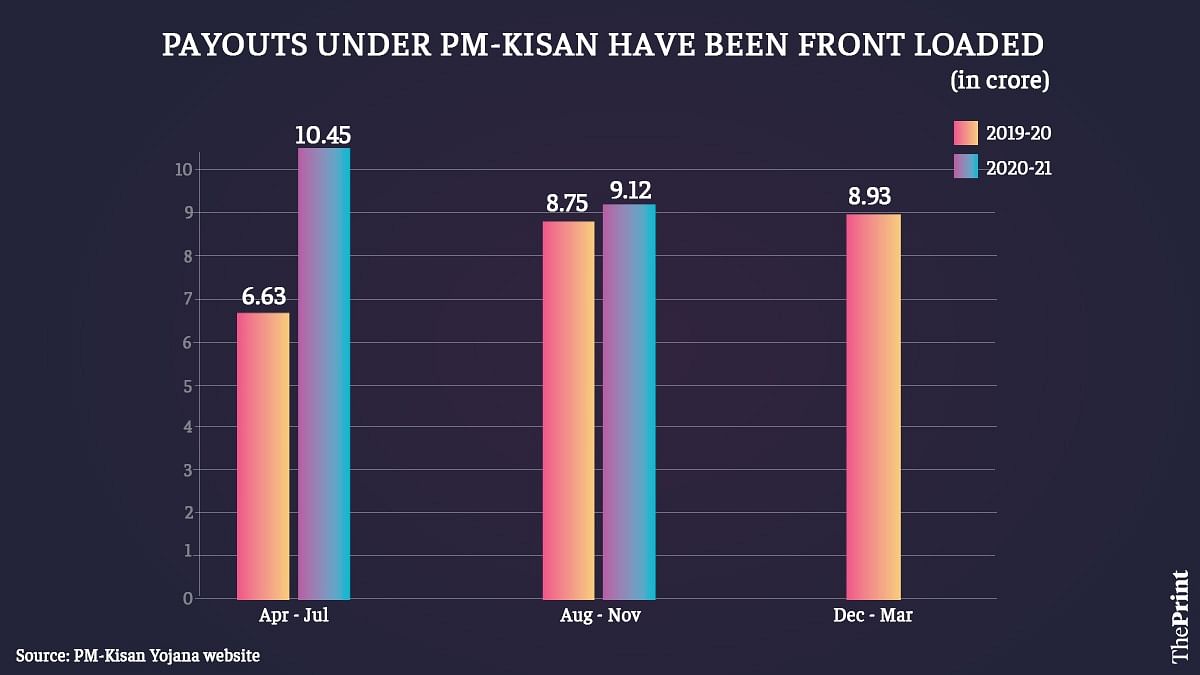

In addition, the government’s cash handouts — Rs 500 per month deposit in Jan Dhan accounts — came to an end in June. The upfront payment under the PM-Kisan Scheme also helped in augmenting farmer incomes but only temporarily. The government’s free foodgrain scheme, however, has managed to reach most of the people.

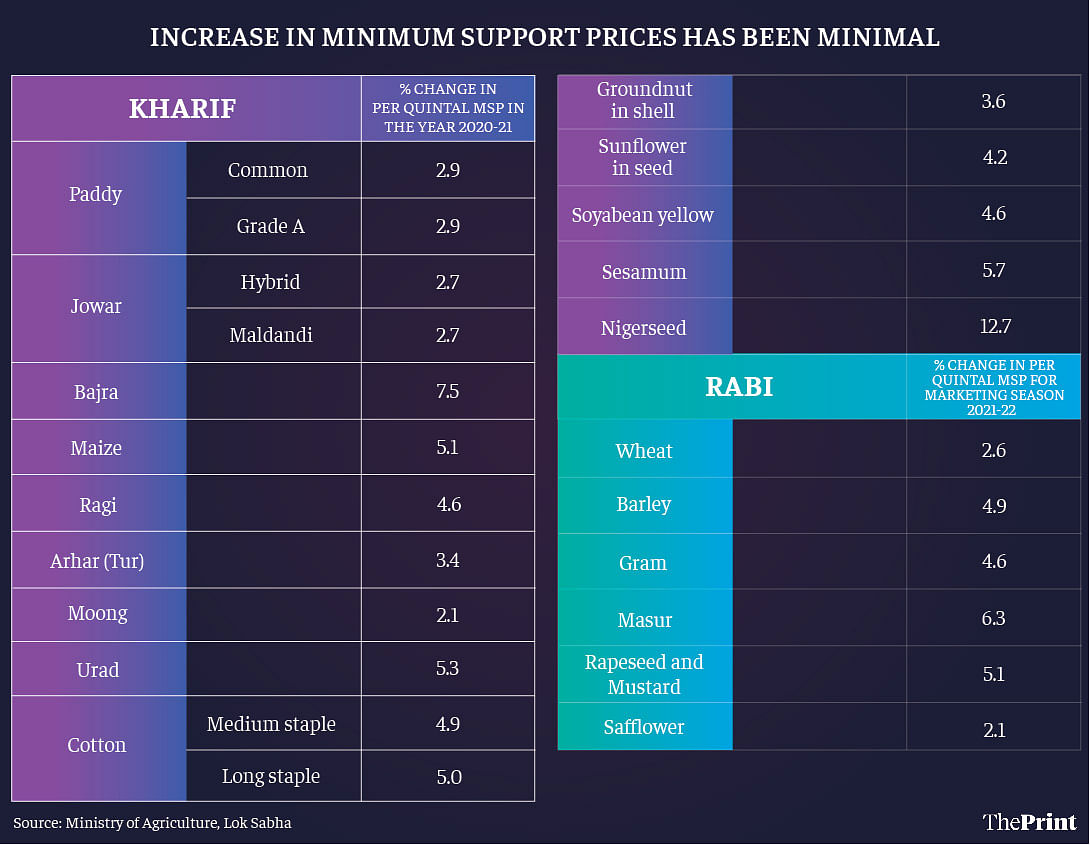

The negligible increase in minimum support prices (MSP) is also unlikely to provide a boost to farmer incomes. The MSP increase for all crops announced by the government this year was in the range of 2-8 per cent with the exception of one.

MSP is the price at which the government procures certain foodgrains, pulses and produce from farmers.

However, the government does not procure the entire produce, leaving many to be dependent on market rates that are much lower. In addition, inferior quality produce may mean no government procurement.

Abal Jagdishbhai, a 25-year-old from Lakhapar village who used to work at a concrete factory in Rajkot, returned to help his farmer father. To reduce their losses from cotton, the family moved to a comparatively less risky crop of groundnut. But rains this season played havoc with the crop and he is now anticipating a 30 to 40 per cent lower price.

“Last year, to improve irrigation for our fields, we got a water tanker and a 20 feet tubewell made with a loan of Rs 25 lakh with our lands as a mortgage. We have monthly interests to pay and the failed crop is not helping our cause,” he says, pointing out that he understands the concept of MSP but it is not always available as an option.

“Sometimes when we have to finance family events or pay back the cooperative banks we have to arrange for money quickly. Since money in the government chain takes time to come, we sell our produce to private merchants at a lower price to arrange quick money,” he adds.

Himanshu points out that a bumper crop production doesn’t mean that farmers will make profits.

“If farmers are getting less money for their produce, then there will be no profits. The announcement of MSP makes no difference if the government does not buy the crops. Government may announce MSP but that does not necessarily mean that the government is buying the produce. Many farmers are forced to sell their produce at market prices lower than MSPs,” he says.

Also read: A new, big shift is taking place in Economics under the shadow of Covid

The crop season

India’s kharif production is estimated at a record 144.5 million tonnes this year, on account of ample rainfall. Production of pulses, paddy and non-food grain crops like oilseeds are projected to grow over last year. However, MSPs are provided for around 22 crops and their different varieties leaving other farmers to be at the mercy of the market.

“Kharif arrivals are yet to really start in large quantities. So, it may too be too early to say that market prices are below MSPs. For paddy, the arrivals will peak in about ten days in Punjab and Haryana. For kharif pulses like toor, urad and moong, the market prices are higher than MSP,” says Siraj Hussain, visiting senior fellow, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

“For soybean and cotton, the market prices are lower than the MSP. In the case of cotton, global exports have gone down but area under cultivation has increased,” he says.

Hussain, who is also a former agricultural secretary, says the “real issue” is data. “The source for all price data is Agmark.net. But price and arrival data are not correctly entered by APMCs (Agricultural Produce Market Committees) in time. If accurate data is not available, it is difficult to make right policies,” he says.

“And this is when trading is done in APMCs and Agmark.net captures data from there. What will happen when large scale trading takes place in the ‘trade area’ out of APMCs? A method to capture correct spot prices in trade areas has to be found and quickly,” he adds.

Rural incomes have also taken a hit with a fall in remittances as many people lost their jobs in cities and returned to their villages, and are working on already overcrowded farms.

Doddaiah, from Buchanahalli in Dodaballapur taluka in Karnataka, had to return to his village from Bengaluru where he worked as a driver with cab service Uber. Responsible for supporting his old parents and a sister who had lost her husband in an accident a few years ago, Doddaiah returned after not being able to pay his house rent.

He is also saddled with a car loan of Rs 5 lakh for purchase of a Tata Indigo. “I came home and began working in the fields as there were no people to help us during the sowing season. I was able to send home around Rs 20,000 each month after paying my EMI, house rent and food expenses. But now, I have to struggle to pay my installments,” Doddaiah says.

The fall in incomes has also meant that for any medical emergencies, families are dependent on local money lenders or taking loans against their assets. Gold loans have become a preferred mode for many.

“One of my cousins tested positive. We had to spend money from our pockets. We mortgaged my sister’s gold so that we have some money to get by at this time,” Doddaiah adds.

Slump in rural consumption

Falling incomes has also translated into reduced purchasing power for people in rural areas. They are cutting back on their spending and also picking up more goods on credit.

For Kesar’s family, daily wage labourers managing fields on the outskirts of Jamnagar for an owner who lives in the city, buying milk is a luxury her family cannot afford. “We drink tea in water because we cannot afford to buy milk. Sometimes when we feel like we have extra money, we buy Rs 10 packets of milk for our children. We stopped drinking milk when the cost touched Rs 50,” she says.

To provide nourishment for her family, Kesar grows small patches of vegetables and pulses on the farm.

Chotu, who runs a kirana shop in UP’s Sheikhupur, has many unsold items in his shop. “The sale of biscuits, coke and even soap has been hit.”

He also points out that more people are buying on credit significantly. “Earlier also people used to buy things on credit, but the amount used to be around Rs 500, now they do not hesitate to buy things worth Rs 1,500 on credit,” he says.

Even barbers like 26-year-old Ejaaz Khan are faced with a sharp fall in customer footfalls. “Before the lockdown, around 60-70 people used to visit my shop daily, but very few people are visiting now. But it is not only because of Covid,” says Khan.

“Nobody in the village has Covid now. Those who were infected have recovered. When people do not have money to buy ration, who is going to get a haircut,” he adds.

Also read: India’s women entrepreneurs look to survive the pandemic by remodeling their business

Dairy and fisheries also hit badly

Not only agriculture, the dairy industry and the fisheries industry is also facing subdued prices.

In Tari Gaon, over 80 per cent people belong to the Kaibarta community, which is primarily engaged in fishing. With markets closed, fishermen are selling their fresh catch in nearby villages at low prices.

“We are forced to sell the small fish for Rs 15 to Rs 30 in other villages. In the daytime, we go out looking for leafy greens and Kosu (Taro) to manage something to eat,” says 60-year-old Kamini Kaibarta. The villagers are deriving food from resources of their own environment having exhausted their savings.

For Harpreet Singh, a milkman from Punjab’ Barnala who has been in the business for 15 years, the pandemic has brought about a complete fall in demand leading to lower incomes. “Most of our suppliers have discontinued their contracts thanks to Covid-19,” he says. His monthly income has fallen from Rs 85,000 to Rs 22,000.

Unemployment issue as many educated youth unwilling to till farms

Many villagers who have returned are also not keen to work in the farms or do NREGS work.

Ravi Prakash is one such young migrant who returned to his native Tevathu village in Aligarh. He was working as a waiter in Noida’s Knowledge Park and earning up to Rs 12,000 per month before the pandemic. “There is no work in the village except farming, I don’t like it here. I want to go back to the city,” Prakash says.

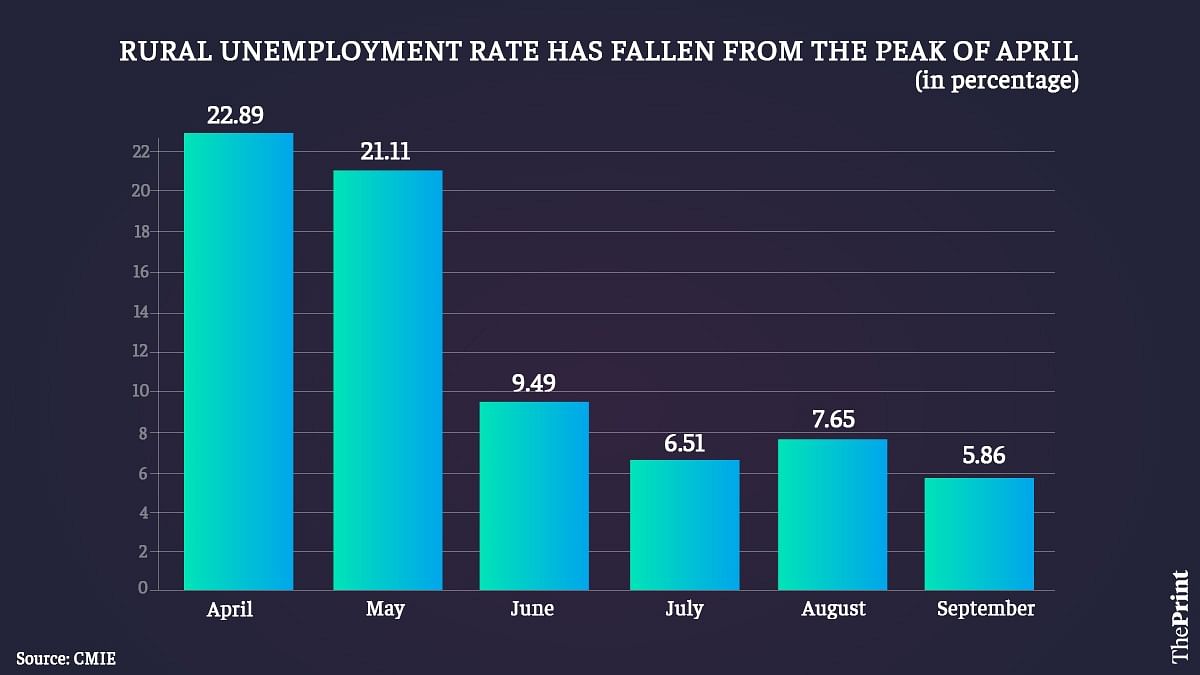

CMIE data shows that rural unemployment fell to 5.86 per cent in September from 7.65 per cent in August. However, disguised unemployment may be rampant.

Farmer Kehri Singh’s two sons, graduate Bablu Kumar and matriculate Udaypal, were also working in Noida and Gurugram, respectively. The lockdown rendered them unemployed and forced them to return to Tevathu. However, both are now actively looking for ways to get back to the city.

“There is nothing for them in the village. They are educated and do not prefer to work here,” says Kehri.

Karishma Hasnat, Aneesha Bedi, Rohini Swamy, Shanker Arnimesh and Rishika Sadam contributed to this report.

Also read: India’s public debt ratio to jump to 90% due to Covid, IMF says

Poor linkage of facts and narrative. All facts are either misinterpreted or eventually dismissed by the authors to support the narrative. For eg, MNREGA utilization is possibly lower because a large portion of the workforce has migrated back to the cities as they opened up. Improvement in unemployment numbers are dismissed. Problems like crop damage which is a part of all havest seasons are cited to support the story. The so-called economic indicators that are down (as quoted by JNU professor) are never cited. On the other hand, a lot of indicators like FMCG sales point towards yoy growth. Terrible article on the whole.

Poor linkage of facts and narrative. All facts are either misinterpreted or eventually dismissed by the authors to support the narrative. For eg, MNREGA utilization is possibly lower because a large portion of the workforce has migrated back to the cities as they opened up. Improvement in unemployment numbers are dismissed. Problems like crop damage which is a part of all havest seasons are cited to support the story. The so-called economic indicators that are down (as quoted by JNU professor) are never cited. On the other hand, a lot of indicators like FMCG sales point towards yoy growth. Terrible article on the whole.

This is a very comprehensive report. Kudos to journalist!

ROTTING CROPS,WEEPING FARMERS ETC ETC; I SUGGEST YOU TO TAKE UP PAST HISTORY OF DEADILY CLIMATE CHANGES WHEREIN AS PER STATISTICS MORE THAN 5 LAKH FARMERS HAVE COMMITTED SUICIDES IN INDIA .I CALL IT THE GREAT DYING AS HAPPENNED IN THE PAST MASS EXTINCTION OF DINOSAURS. THIS GREAT DYING ACTUALLY STARTED FROM LATE 1990’S AND IS CONTINUING TILL TODAY AND IT IS DUE TO CROP FAILURES AND DEADILY CLIMATE CHANGES AND IT MAY NOT STOP ALSO.PLEASE INVESTIGATE AND REPORT CORRECT FACTS TO THE NATION/WORLD.