-On September 3, 2020, a BJP functionary came up with ‘Modi Idli’ in Tamil Nadu in direct competition with the highly popular ‘Amma Idli’. Additionally, Modi and ousted Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak both have suits with their names embroidered all over them.

-Modi criticized IIM Shillong for prefixing Rajiv Gandhi’s name superfluously. According to Modi such tagging caused confusion in the minds of applicants that it was a privately run management institute.

-A Right to Information query raised in 2013 was answered that over 450 schemes, building projects, institutions, etc. were named after the three members (Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi) of the Nehru– Gandhi family.

-Modi changed his appearance and grew a flowing beard and long hair during the Kolkata assembly election campaign. Popular media compared it with Rabindranath Tagore.

What insights above instances offer for a vast liberal electorate democracy that is India?

“They tell over to themselves with vast amusement that a crafty scoundrel or spell-binder could pass off on the people of Paris or London (Jean-Jacques Rousseau).”

Plato’s fierce aversion and distaste for liberal democracy emerges from his proposition that it facilitates the evolution and growth of demagogues, who eventually mutate into tyrants. A democratic city in Plato’s view is sustainable only when its leaders are selfless and not demagogic, which is an impossibility due to the differential capability among democratic men who are free to pursue an enterprise of (their) choice. Therefore, logically and conveniently, demagogues equally possess “the license to do what (they) he wants”.

Aristotle, Plato’s disciple, in his Politics even recognizes democracy’s flaw and the potential instability it faces caused by “demagogues”, who alternately “stir up” and “curry favor” with the people.

Jason Stanley more recently shared Plato’s and Aristotle’s apprehensions about liberal democracy and proposed that it is for namesake only. Specifically, when it does not somehow constitutionally prevent the emergence of propagandist demagogues. He argues:

“A certain form of propaganda, associated with demagogues, poses an existential threat to liberal democracy. The nature of liberal democracy prevents propagandistic statements from being banned, since among the liberties it permits is the freedom of speech. But since humans have characteristic rational weaknesses and are susceptible to flattery and manipulation, allowing propaganda has a high likelihood of leading to tyranny, and hence to the end of liberal democracy.”

Thus, there is a natural incentive in having precautionary knowledge about the prevalence of demagogic and propagandist personality characteristics in leaders of a liberal democracy. Social scientists relate such leadership styles with personality traits such as Narcissism and Machiavellism.

Also read: What if coronavirus crisis had hit India under Manmohan Singh, not Modi

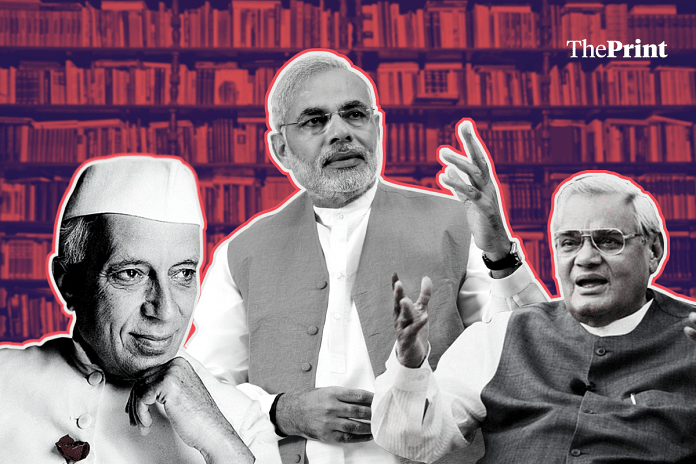

Nehru’s jacket and mass appeal, Indira Gandhi’s sari and stoutness, Vajpayee’s poetry and philosophical pauses, Manmohan’s reticence, and Modi’s charismatic rhetoric: do these personality characteristics have any implications for their leadership behaviors and decisional attitudes? It is an extraordinary and overwhelming enquiry.

While we find umpteen investigations in the American context where researchers and scientists have successfully established personality-behavior linkages for U.S. presidents, scarcely do we find such systematic accounts for prime ministers of India, the world’s largest and most complex democracy.

The unavailability of such an account is baffling yet expected. Finding a theoretically valid framework that may be used as a lens to examine political behavior is challenging. Whereas the forced fitting of a framework may produce unreliable results and thus controversies, loose applicability may cause a lack of representativeness and comparability. Even extreme care in the selection of a framework may result in catastrophic controversies, as it may irk a certain set of individuals or institutions that have a contrarian ideology.

Another challenge emerges from availability of information and its presentation. While in certain occasions it appears in abundance, in other cases there is an absolute absence or (even more dangerously) inaccessibility. The propaganda works in a subtle and complex manner in democracies, such that the available information may carry elements which are consciously and deliberately embedded in public ideology through populist media vehicles. Filtering (and digging) them out is tedious and debatable. Even the absence or inaccessibility of information may be due to conscious efforts of certain individuals or institutions who could infer, utilize, and popularize the results of the study in a scandalous and provocative manner.

Also read: Vajpayee-Advani to Modi-Shah: This was India’s decade of political power duos

If Jawaharlal Nehru were to open a Facebook or Instagram account, what would be his display picture? How would that differ pre- and post-Independence? Who all will be there in the photos? Will he have more Twitter followers than Modi?

Public interviews, biographical accounts, his speeches, letters, and autobiographical writings, and other historical accounts of Nehru radiate restrained but immense self-confidence. They display a peculiarly astute ability to think, compare, gauge, plan, and act. There is an alert awareness not only of the political surroundings at home and worldwide, but also of his own strengths and weaknesses. Thus, based on historiographic observations presented in the (following) sections, we may assess the degree to which Nehru’s personality displayed certain traits such as narcissism and Machiavellianism.

Also, in addition to use of ‘often’ versus ‘once’, use of ‘I’ versus ‘we’ in texts of autobiographical accounts indicate a degree of narcissism or Machiavellianism in the narrator. One may now read Nehru, An Autobiography to assess these traits in Nehru as well.

In recent research comparing the personality traits of autocrats and non-autocrats around the world, the personality traits of Prime Minister Narendra Modi seem to score significantly high on certain narcissism and Machiavellianism parameters. A close examination of the existing literature about his communication style, decision-making methods, and general attitude also indicates a strong presence of these parameters in the prime minister’s personality.

The way Modi employs the art of rhetoric while addressing the public – the use of catchy phrases, dramatic pauses, and glorified anecdotes – possibly reflects Machiavellian tendencies. Such a theatrical way of speaking is not uncommon in Indian politics. Efficiency in communicating and appealing to the emotional as well as cognitive sensibilities of the masses is a major factor in ensuring electoral victory in any democracy. Modi’s strong personality, along with a crafty speech delivery, facilitates the moulding and shaping of public opinion.

The nationwide blackout, lighting of candles, the clapping of hands to encourage health workers, the public use of brooms by celebrities and Modi himself to promote the cleanliness drive, the visual campaigning for the promotion of yoga, and the Howdy Modi event that Modi attended in Houston are some examples where the actions of the government were consolidated in the public perception along with the intelligent use of certain optical tools. Popular terms such as “Moditva” and “Modinomics”, the selfie with Modi hashtag on social media, and the renaming of “Nehru jackets” as “Modi jackets” indicate that Modi, the individual, is at the forefront of public perception.

Several Indian movies have also been released in the recent past to either criticize the opposition or to overtly highlight Modi’s accomplishments. Movies such as Thackeray, Tashkent Files, The Accidental Prime Minister, and Indu Sarkar depict the opposition in an awkward light, and the biopics, PM Narendra Modi and Uri: The Surgical Strike, directly promote Modi’s persona and accomplishments.

Therefore, it is difficult to know who between Nehru and Modi would have more Twitter followers, possibly a tie. However, Modi might have to author some books to attain more equal followership like Nehru in scholarly domain.

Excerpted from Narcissus or Machiavelli? Learning Leadership from Indian Prime Ministers by Nishant Uppal. Published by Routledge India, 2021.

Excerpted from Narcissus or Machiavelli? Learning Leadership from Indian Prime Ministers by Nishant Uppal. Published by Routledge India, 2021.