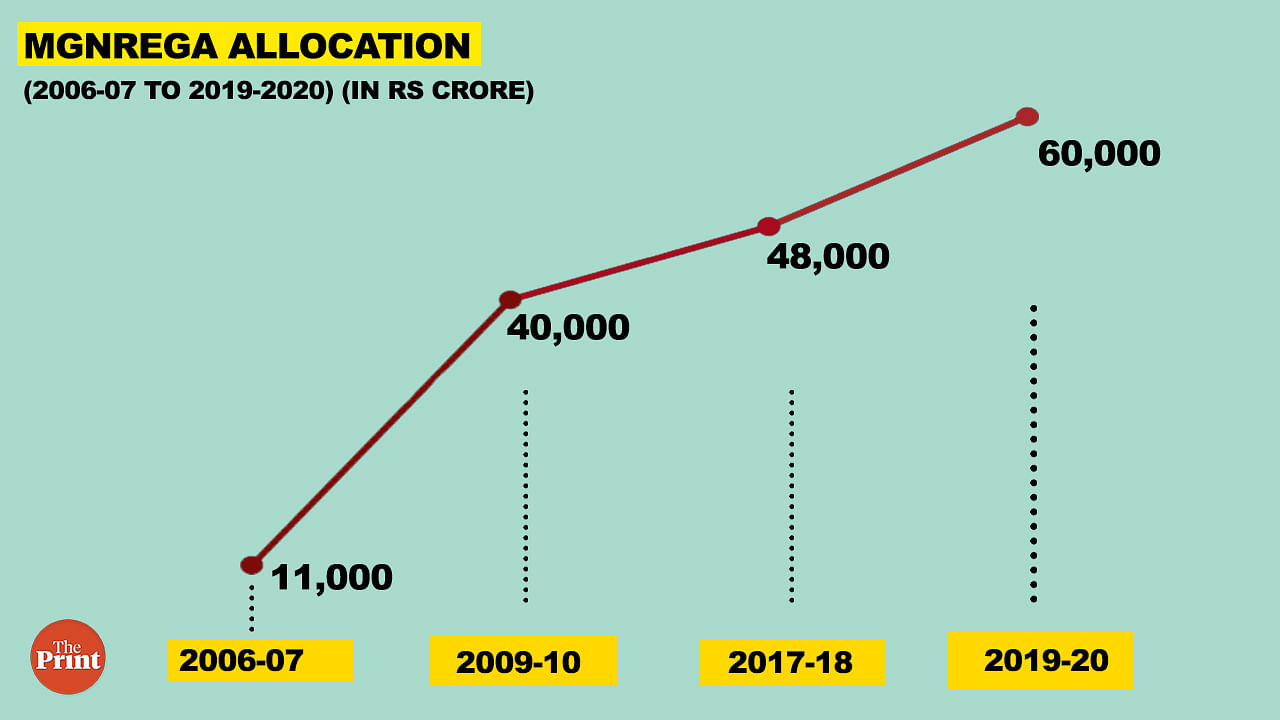

For the first few months of the BJP’s rule under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, there were serious apprehensions about the continuation of the Congress’ flagship rural employment guarantee scheme. But five years later, and with India on course to elect its next government from the 2019 battle, it is safe to say that the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act is here to stay.

It is quite telling that despite an inadequate wage system and persistent problems of payment delays, MGNREGA still continues to gain traction. Recent reports suggest that MGNREGA demand was at a multi-year high during FY 2018-19. Hoping to take forward its initiative, the Congress has in its manifesto for the 2019 Lok Sabha election promised MGNREGA 3.0, which includes raising the number of man-days from 100 to 150 per family per year. The BJP’s poll manifesto, on the other hand, doesn’t mention the programme at all, which is not surprising given the party’s passively hostile attitude towards the programme, which was best captured by the Prime Minister’s famous “living monument of failure” jibe.

Interestingly though, while the Modi government’s initial “attitude and approach” towards MGNREGA raised questions on the BJP’s intent, successive hikes in budgetary allocations can be seen as a telling admission of the programme’s need and efficacy. Whether implied or explicit, there is adequate wisdom in the idea that given the current socio-economic realities and policy rubric, MGNREGA remains one of the primary coping mechanisms for rural families in economic distress. However, the existing wage rate structure and revision systems severely undermine the spirit of the globally-acclaimed programme.

MGNREGA wages vs minimum wages: staggering disparity

In the most recent annual revision to MGNREGA wage rates announced by the Modi government, six states and Union Territories received no hike at all, while a couple of them have had to make peace with a hike of one rupee. It is well documented that MGNREGA wages are way below market rates. In fact, despite the Supreme Court’s direction (July 2014) to rectify this anomaly at the earliest, MGNREGA wages continue to be lower than state-level minimum wage rates (set by the state governments) in most parts of the country. As opposed to a minimum wage (unskilled) of Rs 311 per day, Punjab’s MGNREGA wage rate is Rs 241. Similarly, Gujarat’s MGNREGA wage rate of Rs 199 is almost 35 per cent lower than the notified unskilled minimum wage rate. The Modi government’s own notified national minimum agricultural wage rate of Rs 336 (as of March 2019) is a whopping 60 per cent higher than the newly notified average national MGNREGA wage rate.

In addition, notified wage rates do not usually translate into effective wages. MGNREGA payments are made on the basis of measurement of the work done, and the final wage is accordingly determined for the entire group of labourers who work on the project. In Rajasthan, for instance, during May 2018, as against the notified rate of Rs 192, the effective wage was a paltry Rs 130 per day. Similarly, in June 2018, the average wage rate paid out in Telangana was a mere Rs 139, a 33 per cent cut from the notified Rs 205. In essence, the notified wage rate that is expected to provide a minimum level (or “floor”) for the going market wage rate is in itself a maximum wage rate (or “ceiling”) within the scheme’s design.

Also read: Govt still can’t manage MGNREGA promises, even with ‘highest ever’ fund allocation

It is no wonder then that one of the key reasons behind dwindling motivation of MGNREGA workers across rural India is the low wage rates. A young male labourer in Uttar Pradesh’s Unnao district, who is entitled to Rs 175 per day under MGNREGA, can easily earn twice the amount in brick kilns close to the neighbouring capital city of Lucknow. Not only does the wage differential dissuade him from taking up MGNREGA work, it ensures that MGNREGA work is taken up by the household’s women and senior citizens, which may affect the quality of physical labour. In addition, it undermines one of the scheme’s primary objectives: curbing outward migration from rural areas.

An inadequate revision regime

Furthermore, the process of the annual wage revision in itself is worrisome. Despite having received similar recommendations from two different government-appointed committees that MGNREGA wages revisions be linked to CPI-Rural (CPI-R), the Modi government has continued with the practice of indexing them to CPI-Agricultural Labour (CPI-AL). Notably, the fundamental rationale behind this advice is the composition of the two indices.

Owing to the fact that CPI-AL has higher weightage of food items, it significantly ignores other key expenditure heads such as healthcare, education, transportation and communication. Nevertheless, even a CPI-R linked revision regime will not be adequate to undo the existing gulf between MGNREGA wage rates and market rates (or even minimum wage rates). It is, however, the more appropriate index to be used for subsequent revisions due to its more recent base year and an updated consumption basket. For instance, between 2013-14 and 2017-18, the all-India compounded inflation rate as per CPI-R index was around 21 per cent, almost five percentage points higher than that suggested by the CPI-AL index.

Double booster shot prescription for MGNREGA

The current wage system is, therefore, in need of two layers of correction: current levels and subsequent revision rate — a recommendation that the UPA government-appointed Mahendra Dev panel had also made.

Active measures are needed to align MGNREGA wages with state-level minimum wage rates, while at the same time adopting the most appropriate inflation index for annual revisions. One of the Modi government’s concerns with regard to the alignment with the state-level minimum wage rates is that states may arbitrarily push up minimum wages, thereby squeezing fiscal space at the Centre.

Also read: India’s rural employment plan has been giving fewer & fewer jobs to the most deprived

A possible solution around this concern could be the benchmarking of MGNREGA wage rates against the Centre’s own notified minimum wage rates with provisions for incorporating inter-state differences. In order to avoid a one-time fiscal bump, the government at the Centre may contemplate staggering out the alignment process over a multi-year period, while maintaining the annual inflation-linked revision process.

In fact, the payment delay situation is so dire that earlier this year, lawmakers from Karnataka cutting across party lines (including one of the authors of this article, alongside Union Minister Sadanand Gowda and Karnataka agriculture minister Krishna B Gowda) met the Union Rural Development Minister Narendra Singh Tomar in order to impress upon him growing disenchantment with the programme owing to payment delays.

The bottom line remains that MGNREGA is here to stay. By bestowing upon them the right to work and earn, the programme has created a formidable social security net around economically-vulnerable rural families. State governments across the country have been leveraging the scheme’s reach during times of rural distress. Even Prime Minister Modi, who had in February 2015 famously derided the scheme as a living example of the Congress party’s failure, acknowledged its efficacy when, later that year, his Cabinet cleared a proposal hiking the allotted number of man-days from 100 to 150 per family in drought-hit areas.

Nevertheless, through various means, the scheme has been severely undermined over the last five years. Depressed wage rates comprise one such channel, and need to be addressed if the scheme and its beneficiaries are to be treated fairly.

Professor Rajeev Gowda is Rajya Sabha Member (Karnataka) of the Indian National Congress, and the convener of its Manifesto Committee for the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections.

Kartikeya Batra is a PhD student at the University of Maryland, College Park (Economics department), and has worked on rural economics in four northern states as part of Evidence for Policy Design India, a think tank run by Harvard Kennedy School and Chennai-based IFMR-LEAD.