Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave two main reasons for demonetising currency with denominations of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 on 8 November 2016. First, it would allow the state to seize the wealth in the economy that was accumulated through undeclared income. Hence, this was to be a decisive blow against corruption. Second, it would eliminate the scourge of counterfeit currency that was circulating in the economy. This second motive, while laudable, seemed aimed at a small target because estimates from the Indian Statistical Institute suggested that counterfeit currency accounted for a bare 0.025 per cent of the currency in circulation.

In subsequent days, two other motives were added to the narrative. Third, demonetisation was intended to be a way of pushing India toward a modern digitised economy, which would be less reliant on cash. More digitised payments would bring a larger share of the informal Indian economy into the organised and formal sector. Fourth, by forcing people to convert their old cash into the new currency through the banking system, it was both bringing unaccounted money into the formal tax network and generating greater digital footprints to track individuals and firms who were hitherto hidden from the tax network.

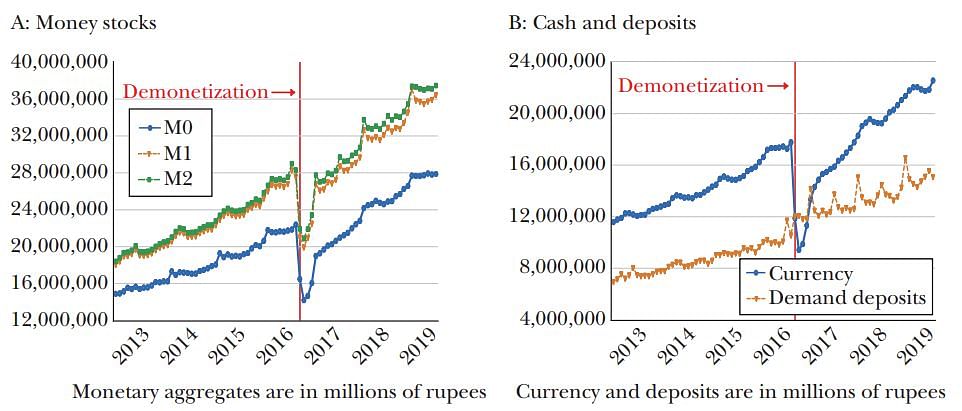

After an extended counting process, when the dust cleared, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced that over 99 per cent of the demonetised currency had been returned to it through the commercial banks. Moreover, within a year of the demonetisation, currency in circulation in the Indian economy was also back to its pre-demonetisation level.

Figure 1: Demonetisation and money stocks

M0 measures currency in circulation, plus deposits by bankers and others with the Reserve Bank of India.

M1 includes currency, demand deposits with the banking system, and other deposits with the RBI.

M2 adds savings deposits of post office savings banks to M1.

While the move was initially hailed as courageous and transformative by some commentators, the mood rapidly gave ground to widespread concerns regarding: (1) the preparedness of the Reserve Bank of India to manage the process of remonetising the economy, (2) the potential of demonetisation to achieve the stated goals, (3) and the costs of the move for the Indian economy. What does the evidence suggest about the effects of India’s demonetisation?

Also read: It’s actually Modi govt’s fault that only 1.5 crore Indians pay income tax

Mostly failure

The evidence points to demonetisation having mostly failed to have achieved its stated objectives. The goal of eradicating black wealth and corruption by demonetising currency was problematic from the start, given the widespread acknowledgement of the fact that undeclared income is seldom held for long periods in terms of cash. Moreover, demonetising currency, which attacks a stock, does little to impede the fresh creation of undeclared income, which is a flow.

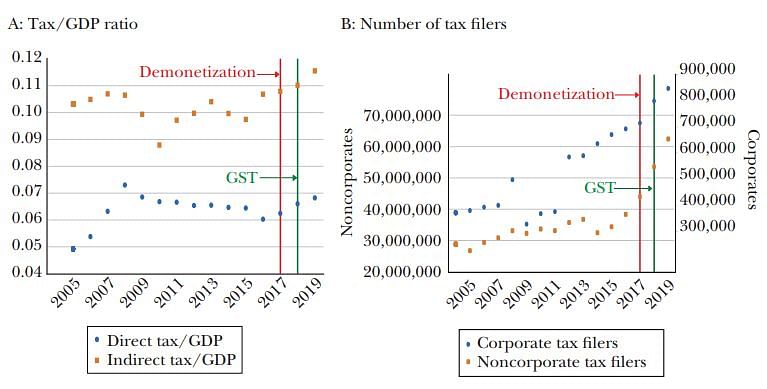

An examination of the growth in digitised payments, in the tax base and in tax revenues, suggests that the move achieved little in terms of changing the pre-demonetisation trends in these measures. Digitised payments were growing exponentially in India prior to 2016, and they have continued on the same nonlinear trend. I also do not detect any systematic impact of demonetisation on either the number of tax filers or tax revenues.

Figure 2: Demonetisation and tax revenues

Note: The figure in the left panel depicts the tax-GDP ratio for both direct and indirect taxes for the period 2005–2019. The figure in the right panel reports the number of tax filers in India during 2005–2019. The left axis reports the number of noncorporate tax filers, while the right axis reports the number of corporate tax filers.

On the cost side, however, there appears to be strong evidence that demonetisation reduced output and employment, especially in the informal sector. However, these losses were likely temporary rather than being permanent. On balance, demonetisation appears to have failed the cost-benefit analysis of public policy initiatives: it had little success in achieving its stated goals while having imposed significant costs on the public.

Also read: Fake banknotes seized in India doubled after demonetisation, Gujarat topped list: NCRB

Preparedness of the RBI

Prime Minister Modi announced the demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency bills on 8 November 2016. It was later revealed that the central board of the Reserve Bank of India had met earlier that evening to consider a letter from the Ministry of Finance that it had received the previous day, along with a memorandum from a deputy governor recommending the demonetising.

The board approved the proposal, but not before making a few trenchant comments. It noted that the measure may not have the desired effect on black money because most people do not hold undeclared wealth in cash. It further worried about the negative effects on growth that were likely to occur in the short run.

Possibly the most damning observation was that the primary fact on which the Modi government had based its proposal—that the supply of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 bills had far outstripped the growth rate of the economy—was simply wrong. The board pointed out the embarrassing fact that the Modi government had compared GDP growth in real terms with the growth of currency supply in nominal terms. In fact, nominal GDP growth had summed to over 80 per cent between 2011 and 2016 and hence was in line with the growth of the currency bills to be demonetised.

The preparation of the RBI came into severe focus almost immediately as ATMs across India ran out of cash for long periods of time.

A further source of concern came in the form of multiple circulars that the RBI issued — 57 official circulars between 9 November and 31 December 2016, which kept revising the conditions under which the public could make deposits, withdrawals, and exchanges of the demonetised currency.

The combination of the slow stocking of ATMs with the new cash, the spate of revised notifications, the limited supply of new 500-rupee bills, and the relative excess of new 2,000-rupee bills, which were less useful for transactional purposes, suggested that the institution tasked with implementing the policy was not adequately prepared. Rather, the policy was thrust upon the RBI, which then scrambled to implement the policy as best as it could.

Also read: Three years after demonetisation, survey finds people still prefer cash payment

Economic costs of demonetisation

As an indicator based on current data, Figure 3 shows the path of four different interest rates in India since 2013 as well as the path of bank credit and bank deposits. The interest rates shown in the figure are the repo rate, which is the policy rate of the RBI; the call money rate, which is the rate at which short-term funds are borrowed in the overnight money market; the bank lending rate; and the bank-term deposit rates. All the interest rates other than the repo rate are weighted averages.

Figure 3: Interest rates and bank credit conditions

Note: The figure shows the monthly data on different interest rates during January 2013–January 2019 and bank credit and bank deposits in India during January 2013–September 2019. The repo rate is the policy rate of the Reserve Bank of India, and the call money rate is the rate at which short-term funds are borrowed in the overnight money market. The bank lending rate is the weighted average lending rate of banks, while the deposit rate is the weighted average bank-term deposit rate. Bank credit and bank deposits are reported in millions of rupees.

Because banks were flush with deposits during the months immediately after the demonetisation shock, one might have expected credit conditions to have become significantly easier. However, none of the interest rates showed any sharp movement off their long-run trends around the demonetisation date, nor did bank credit pick up in any significant way. In fact, bank credit fell marginally on impact. This is somewhat surprising given that total bank deposits rose by almost Rs 6 trillion on the impact of the shock.

The unemployment rate is another variable. Figure 4 shows the monthly unemployment rate as reported by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) since 2016.

Figure 4: Demonetisation and unemployment

Note: The figure shows the monthly unemployment rate in India for the period January 2016−October 2019. It is based on a nationally representative household survey.

The figure reveals two interesting features. First, the unemployment rate in India was declining throughout 2016. There is hardly any noticeable effect of demonetisation on this declining trend. Second, the unemployment rate begins to rise steeply in India after the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) reform.

While Figure 4 might suggest that demonetisation had a tepid effect on unemployment in India, Vyas (2018) presents evidence suggesting that underneath the declining unemployment rate trend though is a steep decline in the labour force that coincides with the demonetisation quarter.

Using the CMIE monthly and quarterly labour force statistics, Vyas documents two facts. First, relative to the three-month period immediately preceding demonetisation (July–October 2016), the number of employed individuals declined by 3.5 million during the period November 2016–February 2017. Second, the CMIE survey also found a dramatic 15 million decline in the size of the labour force between these two periods. Most of this decrease in the labour force was accounted for by a fall in the number of individuals who identified themselves as unemployed. In other words, Vyas suggests that the period of demonetisation coincided with a sharp increase in the number of discouraged workers who simply exited the labour force completely.

Also read: BJP govt must know there cannot be economic growth without a strategic approach

Conclusion

The effect of demonetisation in terms of its stated goals was limited at best. Because almost all the demonetised currency was returned to the central bank, it failed in its goal of taxing undeclared income and black (undeclared) wealth. Relative to past trends, demonetisation does not appear to have had any significant effect on the tax base.

The costs of demonetisation are difficult to estimate. However, there are clues. As an example, the large increase in bank deposits during the demonetisation period caused a surplus of loanable funds. However, there was almost no impact of this either on the amount of bank loans or in the average lending rate. This tends to suggest that the economic disruption induced by demonetisation may have caused a deterioration in the perceived creditworthiness of the average borrower.

Existing research on estimating the costs of demonetisation using disaggregated data suggests that it could have lowered output by as much as 2 percentage points during the demonetisation quarter. Almost all work in this area also suggests that the costs were temporary and lasted at most two quarters. Available labour market statistics suggest that up to 3.5 million jobs may have been lost during the three months following demonetisation while 15 million people may have exited the labour force.

It is surprising, however, that the aggregate statistics do not reveal much effect of the demonetisation shock. On January 31, 2019, India’s Central Statistics Office released a revised GDP series, which estimates real GDP growth in the fiscal year 2016–2017 to have been 8.2 per cent, the highest since 2011–2012. This implies that India’s annual GDP growth increased by 20 basis points in the year of demonetisation, relative to the previous year. It is possible that growth in the non-demonetisation quarters, particularly the period April–September 2016, saw very rapid economic growth that was partially undone by the negative effects of demonetisation during the rest of the year.

Another issue of importance is the distributional impact of demonetisation. Demonetisation was packaged as a measure against relatively wealthy individuals who had accumulated undeclared wealth. However, anecdotal accounts suggest that it may instead have disproportionately affected the relatively poorer households working in the informal sector.

The Indian experience suggests that demonetisation is likely to have a better chance of achieving the goals of fighting crime and tax evasion if larger denomination bills are demonetised. Governments contemplating such moves in the future may be better advised to demonetise large denominational bills rather than those that are heavily used for daily transactions.

Amartya Lahiri is Royal Bank Faculty Research Professor, Vancouver School of Economics, University of British Columbia, Canada.

The article is an edited excerpt from the author’s paper ‘The Great Indian Demonetization‘, which was first published in the American Economic Association’s Journal of Economic Perspectives. Read the full paper here.

@ Gururaj

It is better to have undisclosed business with resulting employment which in turn leads to more consumption and revenue.

In ideal world economy should be fully formal but should never be at the cost losing jobs. Demo, complicated and shabbily implemented GST and

now “tax terrorism “with plummeting business investment have severely dented economy.

Good and apolitical analysis of demo. Critics of Demo have to understand this. It was not just informal sector that was adversely affected by demo, but also undisclosed businesses. For example, someone, who does Rs.1 crore turnover may disclose only Rs.50 lakhs. His undisclosed business of balance Rs.50 lakhs also adds to the economic activity and value without the tax liability. This part is like cancer which grows without making the body healty. Can anyone deny that demo was a blow to such cancerous growth? Incidentally, why place RBI on a higher pedestal, as a good guy trying to save the world? RBI is also a part of government. It is a statutory bank under Government’s control. It is as much a part of government when it comes to monetary decisions.

Only BJP profited by demonetization.