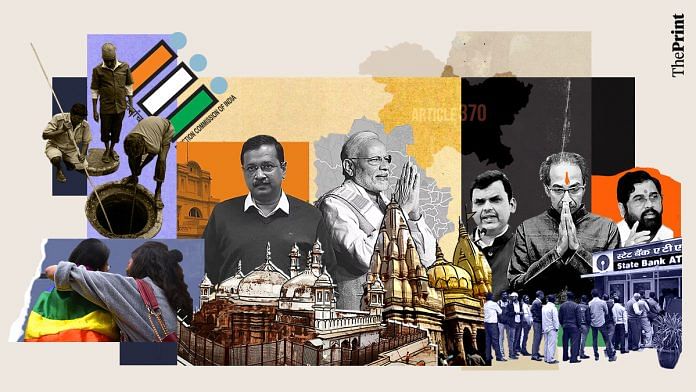

New Delhi: From demonetisation to the abrogation of Article 370 of the Constitution, courts delivered several important judgments in 2023.

The Constitution benches of the Supreme Court delivered at least 18 judgments in 2023 — disposing of several issues of national importance. More than one of these dealt with fraught relations between the Modi government and administrations led by Opposition parties in states.

ThePrint brings you a list of 11 important judgments passed by the Supreme Court as well as the high courts.

Demonetisation

The year began with the Supreme Court, on 2 January, upholding by 4:1 majority the Narendra Modi government’s November 2016 decision to ban bank notes of the Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 denominations.

The five-judge bench comprised justices S. Abdul Nazeer, B.R. Gavai, A.S. Bopanna, V. Ramasubramanian, and B.V. Nagarathna. The majority judgment was authored by Gavai, while Justice Nagarathna differed from the majority view.

The court held that the central government is empowered under Section 26 (2) of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act to initiate a demonetisation exercise through an executive order for all series of bank notes.

The provision allows the central government to declare that “any series of bank notes of any denomination shall cease to be legal tender” after a recommendation from the central board of the RBI. In fact, the majority verdict differed from the minority judgment on the judges’ interpretation of this provision.

The majority judgment asserted that individual interests must “yield to the larger public interest sought to be achieved” by the government’s move. The restrictions imposed through demonetisation were reasonable, in the public interest, and aimed at curbing evils of fake currency notes, black money, drug trafficking, and terror financing, it said.

Therefore, the notification also satisfied the “doctrine of proportionality” — action shouldn’t be more drastic than it ought to be — as the measures undertaken were strongly linked to the objective it sought to achieve, the court held.

Article 370 of the Constitution

The Supreme Court on 11 December unanimously upheld the abrogation of Article 370 of the Constitution, which bestowed special status on the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Article 370 exempted Jammu and Kashmir from provisions of the Indian Constitution, allowing it to frame its own constitution. It also spoke about the applicability of central laws to the state.

Parliament needed the state government’s concurrence for applying laws to the state, except for those relating to the domains of defence, external affairs, and communications.

Article 370 also empowered the President to apply different provisions of the Constitution to the state. But it required the President to secure the concurrence or consultation of the J&K government before issuing such an order.

In its judgment, a five-judge Constitution bench ruled that the President could unilaterally apply all the provisions of the Indian Constitution to Jammu and Kashmir, and declare that Article 370 ceases to operate. It also held that Article 370 was a temporary provision.

However, the Supreme Court did not look into the validity of the bifurcation of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union territories (UTs) through the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019. This was in view of the statement given by solicitor general Tushar Mehta (during the hearing) that statehood would be restored and the UT status was temporary.

Also Read: What next for LGBTQ community? Read fine print in SC order—civil union, adoption, Bon Jovi

Marriage equality petitions

On 17 October, the Supreme Court ruled out legalising same-sex marriage in India.

A five-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud declared that the court cannot tweak or read into the Special Marriage Act (SMA) — the law governing inter-faith marriages in India — to grant legal recognition to marriages between queer couples.

The court left it to Parliament to frame a law for extending institutional acknowledgement to such relationships, adding that the current legal framework does not support such a union.

The minority verdict, by Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice S.K. Kaul, advocated for a right to form ‘unions’ by non-heterosexual couples.

However, the five judges unanimously held that transgender persons in heterosexual relationships have the right to marry under the existing framework, including personal laws that regulate marriage.

Delhi government vs L-G on services

On 11 May, another five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court allowed the Arvind Kejriwal-led government to exercise its executive as well as legislative authority over the officers of various services, including those who are not recruited by it and have been allocated to Delhi by the Union of India.

This included the authority to transfer and post officers within the government, frame service rules for them, or undertake any other measure for governance purposes, including passing a law in the legislative assembly.

However, within days, the Modi government promulgated an ordinance creating a new statutory authority to handle transfer and posting of civil servants in the national capital, effectively negating the court order.

The National Capital Civil Service Authority (NCCSA) is headed by the chief minister of Delhi, with the chief secretary and the principal secretary of the home department serving as members.

The Delhi government challenged this ordinance in the Supreme Court, and its petition was referred to another Constitution bench on 20 July. The ordinance has since been formalised as an Act.

Maharashtra crisis

In May, a five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court pronounced its verdict on the political fallout in Maharashtra last year following differences in the Shiv Sena between groups owing allegiance to Chief Minister Eknath Shinde and his predecessor, Uddhav Thackeray.

Shinde broke away to assert his own faction’s supremacy, and became the CM in July 2022 with the BJP’s support.

In June 2022, as a rebellion began to take shape in the Shiv Sena, the Shinde faction was served with a disqualification notice by the deputy speaker for acting against the party whip while voting during the Member of Legislative Council elections.

However, this notice was questioned by Shinde and others, who asserted that the deputy speaker could not have proceeded on the disqualification petitions, pending a removal notice against him.

In June 2022, the court granted interim relief to this group by extending the time to file their responses to the disqualification notice, till 12 July. Before this, Shinde and the 15 other legislators against whom disqualification notices were issued were supposed to submit their written responses before the deputy speaker by 5.30 pm on 27 June.

Two days later, the Supreme Court allowed the floor test called by the then Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari, as it refused to give any interim relief on a petition filed by the Thackeray group against the summoning of the assembly by the governor.

The Thackeray faction also filed a fresh petition in the court, challenging the speaker’s decision to recognise the new Sena leader and chief whip from the Shinde faction in the Lok Sabha, instead of the Thackeray faction’s nominee.

The Supreme Court’s Constitution bench ruled in May 2023 that former Maharashtra governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari was not “justified” in asking then chief minister Uddhav Thackeray to face a floor test in the wake of the crisis in his party, the undivided Shiv Sena. The court asserted that a floor test cannot be used as a medium to resolve internal party disputes, and also said that the speaker’s decision to appoint a whip from the Eknath Shinde group was “contrary to law”.

However, the bench did not restore Thackeray as the chief minister of Maharashtra because he did not face the floor test and had tendered his resignation on 29 June 2022.

The court directed the speaker of the assembly to decide on the disqualification of MLAs who switched to the Shinde faction.

Governor’s powers

This year, several governors — who are the executive heads of states, appointed by the Centre — found themselves at odds with the elected state governments. One of the main points of dispute was governors not giving their assent to crucial bills passed by the state legislature.

In November this year, the Supreme Court held that if a governor decides to withhold assent to a bill, then he or she has to return the bill to the legislature for reconsideration. This was in a case involving the Punjab government and the governor.

Under the Constitution, when a bill is passed by the state legislature, it has to be sent to the governor. The governor then has four options: They can give their assent to the bill, in which case it will become a law, or they can withhold their consent, or reserve the bill for consideration of the President, or they can return the bill for reconsideration of the state legislature.

The Constitution also clarifies that when a bill could derogate the powers, or endanger the position of the high court, the governor should reserve it for the President’s consideration.

However, if a bill is returned to the legislature, and then submitted again to the governor, it is mandatory for the governor to assent.

While there is no rigid timeline on how long the governor can take while considering a bill, the Supreme Court in November asserted that the expression “as soon as possible” in proviso one of Article 200 of the Constitution mandates a governor to either give their assent to a bill or return it to the legislature expeditiously.

Also Read: Courts still use ‘jamadar’ as post, need to shed colonial mindset, says SC report

Election Commission

In March this year, a five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court modified the process for appointing members of the Election Commission (EC) of India. The court held that a committee comprising the Prime Minister, the leader of the Opposition and the Chief Justice of India will advise the President on ECI appointments. The judgment was passed on a 2015 public interest litigation challenging the constitutional validity of the practice of the Centre appointing members of the EC.

However, in order to overturn the verdict, the central government, in August this year, introduced the Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Bill 2023. This bill said that the chief election commissioner and election commissioners will be appointed by the President upon the recommendation of a selection committee comprising the Prime Minister, a Union Cabinet minister, and leader of Opposition/leader of the largest Opposition party in Lok Sabha — taking the CJI out of the equation.

It was passed by the Rajya Sabha as well as the Lok Sabha in December.

Living will

The concept of living wills or advance directives was introduced in India by a Supreme Court judgment in March 2018. A living will is a document that a person can execute in advance, explaining his/her wish about withholding or withdrawing medical treatment in case of terminal illness or a situation in which they are undergoing prolonged medical treatment with no chances of recovery and cure. This document ensures that in case the person becomes incapable of communicating their wishes about their medical treatment in the future, their desires on withholding or withdrawing treatment can still be implemented.

The 2018 judgment had recognised the right to die with dignity as a fundamental right and laid down guidelines for terminally ill patients to enforce the right, through an advance medical directive for a future situation in which they reach a point of no return.

On 24 January this year, the Supreme Court made the process less cumbersome by modifying the existing guidelines. It did away with the role of the magistrate in execution and implementation of an advance directive, while also simplifying the composition of the medical boards determining whether life-support systems can be withdrawn, and setting time limits for these boards to take such decisions.

Kashi Vishwanath temple-Gyanvapi mosque

On 19 December, the Allahabad High Court dismissed five petitions by the UP Sunni Central Waqf Board and the Gyanvapi mosque committee, holding that a suit filed in 1991 over the Varanasi mosque is not barred under provisions of the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991.

The original suit in this case was filed in 1991 by devotees in the name of the deity ‘Swayambhu Lord Vishweshwar’, demanding that they be allowed to “renovate and reconstruct their temple”, because the Gyanvapi mosque was built at the site of a temple on Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s orders.

While this suit was pending, the Gyanvapi mosque management committee, Anjuman Intezamia Masjid, managed to get a stay on the proceedings from the Allahabad High Court in 1998. The committee had alleged that such a suit is barred by provisions of the Places of Worship Act, which freezes the character of places of worship as they stood on 15 August 1947.

While this stay continued for the next two decades, another attempt was made through an application filed in December 2019, a month after the Supreme Court verdict in the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid case, demanding that the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) should conduct a survey of the disputed premises.

Despite the high court’s 1998 stay, civil judge (senior division) Ashutosh Tiwari allowed the application for an ASI survey of the Gyanvapi complex in April 2021.

The Allahabad High Court stepped in again, criticised the civil judge’s order and stayed it on 9 September in 2021. The Allahabad High Court has now ruled that the suit is not barred by the 1991 law, and the case will be heard by the Varanasi civil judge’s court, which has been directed “to proceed with the matter expeditiously and conclude the proceedings” within six months.

Manual scavenging

In October, the Supreme Court said the Union and the states are “duty-bound to ensure that the practice of manual scavenging is completely eradicated”.

“Each of us owe it to this large segment of our population, who have remained unseen, unheard and muted, in bondage, systematically trapped in inhumane conditions,” the court observed, while issuing a slew of directions.

Among other things, the court enhanced the compensation payable for sewer deaths to Rs 30 lakh from Rs 10 lakh, and said that the minimum compensation to sewer victims suffering disabilities shall be Rs 10 lakh. The court also directed the Union government to take appropriate measures to ensure that manual sewer cleaning is completely eradicated in a phased manner.

Adultery in armed forces

In January, the Supreme Court clarified that its 2018 judgment decriminalising adultery would not impact court martial proceedings initiated against armed forces personnel serving the armed forces for adulterous conduct.

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)