New Delhi: Although Article 370 had become some kind of a “skeleton” over time, it was perceived as something that was still subsisting, outgoing Supreme Court judge Sanjay Kishan Kaul has said.

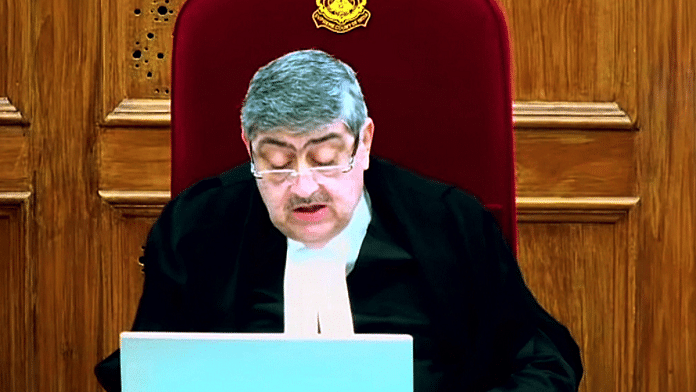

Justice Kaul, who was appointed to the Supreme Court in 2017 and demitted office Monday, was speaking in defence of the apex court’s ruling earlier this month upholding the abrogation of Article 370 — a provision in the Constitution that gave special status to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

In an interview with ThePrint, Justice Kaul also dismissed the criticism that the 11 December ruling of SC’s five-judge Constitution Bench was against the concept of federalism, and the basic spirit of the Indian Constitution.

For instance, on 16 December, former Supreme Court judge Rohinton Nariman had called the court ruling “disturbing” and said that it had a “tremendous impact on federalism”.

However, according to Kaul, “Kashmir was a standalone case in the context of the special provision made under Article 370.”

“It is my belief that this was meant to, at some stage, disappear,” Justice Kaul said, adding that the “provision was part of the chapter in the Constitution that deals with temporary provisions.

He further said that the stage at which it should disappear is a political decision and that is not where the court has “stepped into the picture”.

“I think before I write and have no regrets about what I write. I believe what I wrote is what should be the law,” Kaul said when asked about former judges criticising the Article 370 verdict. He said that as a judge it is “not his job” to keep “the legal fraternity happy”, that differences of perception would always remain and he believes that those who “disagree are entitled to do so”.

“There are many problems which have social legal context and are debated and come in different forms. I would write some judgments where there will be another section which would be happy with it, the section which is unhappy at the moment would be happy with it,” he said, pointing out that the Article 370 judgment is a unanimous view delivered by the top five judges of the Supreme Court.

Justice Kaul also said that the opinion of former judges on the issue did not perturb him as they are merely “opinions”.

“Today, we may have an opinion sitting outside as a common citizen,” he quipped.

In his interview, the former judge also spoke about his minority view on the same-sex marriage petition, his view on judicial appointment, and the problem with listing cases in the top court, among other issues. Here are excerpts.

Also Read: With its Article 370 judgment, Supreme Court has driven a nail through federalism

Same-sex marriage — ‘social changes initiate changes in the law and vice-versa’

As a judge who was part of the nine-member bench which authored a landmark privacy ruling that declared the right to privacy as a fundamental right in 2017, Justice Kaul saw the same-sex marriage case as one for the LGBTQ+ community to move forward — more so after the apex court decriminalised Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC).

Following the privacy ruling, the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling on Section 377 (provision on “unnatural sex”) was a formality, he says. As for the rights of LGBTQ+ community, he said, it has been a social movement that began in 2001 when a petition was filed in the Delhi HC on striking down Section 377.

He was the first judge before whom the petition was listed. It was around the same time when Justice Kaul had joined the judiciary as a judge of the Delhi HC. He was junior in the court’s hierarchy then, and when the bench he was part of issued notice, his senior partners, thinking he would be over-enthusiastic, took away the case from him, he said.

That petition was first dismissed “in limini” (without a hearing), he said. But after the Supreme Court sent it back for hearing, the Delhi HC gave its historic ruling striking down the provision.

Then, in 2013 — five years before the court finally struck down Article 377 — a division bench of the court overturned the Delhi HC’s ruling.

“From 2001 onwards, it took almost two decades before we (SC) finally came to a conclusion (on section 377 IPC) and the government and citizenry also accepted it,” he said.

According to Justice Kaul, “sometimes the law initiates social changes, sometimes social changes initiate the process of law”. The Section 377 IPC ruling, he said, was an endeavour to change the “social thinking process”.

Therefore, the same-sex marriage case was to move a “little bit forward”, he told ThePrint.

This year, the majority view turned down the petitioners’ plea to read same-sex marriage as part of the Special Marriage Act — a secular law that recognises inter-faith marriages. But the minority view authored by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice Kaul opined granting civil union rights to the LGBTQ community. Justice Kaul views this as the “other side of the coin”.

“The idea was to give them (same-sex couples) a recognition to this section who may have different sexual preferences,” he said. Despite the outcome of the petition, the former judge believes that the law won’t remain static on the issue and the government could consider it (same-sex marriage) “a couple of years down the line”.

It’s also possible that the judiciary may change its view, he said. “I think a time will come when the opinion (minority) will find favour,” he said, clarifying that he was not touchy about how the case ended.

Also Read: ‘Peace-lovers to what extent?’ Syama Prasad Mookerjee on why India could lose Kashmir

On judicial appointments — ‘Centre has a say’

Elevated to the Delhi High Court in 2001, Justice Kaul held the chief justice’s post in two high courts — first in Punjab and Haryana HC and then in Madras HC. As chief justice, he presided over their respective collegiums — the body that decides on judges’ appointments.

In 2017, he was elevated to the Supreme Court and was a member of its collegium for 14 months. The Narendra Modi government has frequently accused the collegium of opacity, setting off confrontations between the executive and the judiciary.

But according to Justice Kaul, judges cannot be announced on a “podium”. But he also concedes that the National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC) — a now-scrapped body proposed by the Modi government for the recruitment, appointment, and transfer of judges — should have been given a chance, subject to mild tweaking.

The NJAC was established with an amendment to the Constitution by the Modi government in its earlier tenure in 2014. The body sought to replace the collegium system. It was struck down by SC’s five-judge Constitution Bench in 2015.

“My own personal belief is that somehow NJAC got finished off before giving it a chance. I think given what is happening today, a lot of this could have been avoided, if we had experimented with it (NJAC), tweaked it. Judiciary saying that we would control the appointment process has left much to be desired,” he admitted.

But Justice Kaul also rejects the allegation that under the current collegium system, the government had very little say on judges’ appointments.

“The government also has its own suggestions and they come up before the collegium. There are, at times, very good judges,” he said. “It would not be fair for me to say that just the collegium sits and decides… If you go back to 1950, it’s the same scenario. I think nowhere in the world will the government accept that it has zero role to play in the appointment in the judiciary.”

There were multiple layers of the judicial appointment process, he explained. This involves, in the case of HC appointments, getting a list of names from its collegium and seeking comments from the government of the state in which the appointment is to be made.

The HC also gets informal inputs on possible candidates from the Intelligence Bureau — a body that falls under the central government — before finalising its list and sending it to the Supreme Court collegium, he said.

The SC Collegium also receives formal IB inputs on candidates from the central government. A decision is taken only after receiving these inputs, said Justice Kaul.

In case of objections from the government, the collegium asks for specific inputs. “In many cases, we have sent the names back to the HC,” he said, denying that the collegium doesn’t take note of reservations expressed by the government.

Recommendations are made only after an “across-the-board search is done” in which the best talent is picked up, he said. Inputs from judges who are not members of the collegium but have served in the HC where the appointments are being made are sought before the panel sends a final list to the central government.

“We don’t stand on a podium to do it (selection), it cannot be done,” he said. He also wondered if the appointment of civil servants as government secretaries would be similarly termed opaque. Significantly, the appointment of an officer of the rank of joint secretary is a two-step process involving empanelment and selection by the experts’ panel.

“There are processes for that too (secretary appointment). Similarly, we also have processes that cannot occur standing outside,” he said.

‘Collegium has failed to some extent due to people managing it’

The problem, according to him, with the collegium is that it is a judicially evolved process and is not mentioned in the Constitution. He also concedes to failure in the system — not because it is bad “but because the ones managing it have failed to some extent”.

The collegium system was introduced following a Supreme Court judgment in 1993, commonly known as the Second Judges Case. In this, seven of the court’s nine-judge bench held that the Chief Justice of India was entitled to primacy when it came to appointments in the higher judiciary — that is, the HCs and the SC. This decision was reiterated in 1998, with a modification that SC’s collegium was expanded to consist of the CJI and four senior-most judges of the court.

Through these judgments, the court cemented the principle of judicial independence in appointments.

Justice Kaul said the system was created due to “exigencies and situations” and worked well for a long time. “The post to a judge, in my mind, is not a post for my relatives and friends. It is supposed to be determined on certain parameters and when going through the processes that are required, ultimate selection has to take place and if there are things wanting, criticism is bound to come in.”

He conceded collegium has produced some judges who “did not turn out to be the way as he should have” and said he “personally had faced this scenario” as Chief Justice of two HCs.

‘Element of subjectivity in SC appointments’

As a judge of SC, Justice Kaul had taken on the government on the judicial side over appointments. He did not deny that there is an “element of subjectivity” when it comes to appointments in SC. But he did not approve of the “rush, push, and pressure” to get elevated to the top court.

Non-elevation or being ignored for SC is not a reflection of an HC judge’s competency. “It’s not that a SC judge gets anything more than what a HC Chief Justice gets,” he remarked.

Appointments to SC are based on multiple factors, such as who would be a future CJI, representation of gender or backward community, and even representation of a specific HC.

“Seniority is one of the factors taken into consideration for nominating a judge to the apex court,” he said.

Justice Kaul was firm on the judiciary having a final say on the transfer of HC judges. This, he said, is the only solution in the absence of a “workable impeachment system”.

However, he was quick to add that every transfer should not be perceived as punitive or raise a question over a judge’s integrity. Many happen for better administration of justice and also include cases where a judge volunteers to get transferred, he said.

“Unlike the appointment process, where government plays a role and will have to play a role, transfer matters should be a judiciary’s call because you are determining where that appointed judge is best suited to carry out his task,” he said.

Justice Kaul also shared his views on the functioning of the SC. According to him, matters such as listing of cases can be sorted out within the system.

“Judiciary cannot be a glasshouse. Yes, at the same time there is a need for transparency,” he said.

He also disapproved of the press conference that four judges of the top — justices J Chelameshwar, Ranjan Gogoi, Kurian Joseph, and Madan Lokur — held in 2019 against the then CJI Justice Dipak Misra over the listing of cases. Justice Kaul, who days before his retirement, expressed shock when the matter related to judicial appointments was not put up for hearing before him despite a fixed date in the case, said the press conference “did not help anybody, except causing some disturbance.”

Judges are not indispensable, and if a matter does not get listed before a bench, someone else will hear it, he said. But he did expect a “reasonable approach” from a CJI to frame a roster (listing of cases). And, if issues continue, then they must be sorted out with the CJI, he said.

On the judicial appointment case being dropped days before his retirement, Justice Kaul said he spoke to the CJI and left it to him to determine how it was not listed.

Asked whether it was correct on his part to hear the case, even when he was a collegium member, he responded: “It’s rather peculiar. At the time when I took it up (first, when not a collegium member) there were voices raised that I, not being part of the collegium, should not have done it. It was then told to me by the then CJI, (that) maybe there were some concerns on the government’s part or otherwise.”

He expressed concern over SC and HCs becoming a political battleground and growing intolerance over differing opinions. He also complained that the top court was fast getting converted into an appellate court. With more time being spent on large disputes, many cases with smaller issues are getting pushed to the back burner, increasing the court’s backlog, he said.

“Between the friction, unfortunately, everything is coming to court. I believe there has to be a greater give-and-take everywhere. It cannot be my way or highway, there has to be acceptance of differences of opinions,” he said.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: 31% of judges’ posts vacant in high courts, 21% in district judiciary, finds SC report