New Delhi: While the Supreme Court refused to legalise same-sex marriages in India Tuesday, Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice S.K. Kaul in their opinions advocated for a right to form “unions” by non-heterosexual couples.

The CJI asserted that “material and expressive entitlements which flow from a union must be available to couples in queer unions”.

He added that the “freedom of all persons including queer couples to enter into a union is protected by Part III (pertaining to fundamental rights) of the Constitution”.

“The failure of the state to recognise the bouquet of entitlements which flow from a union would result in a disparate impact on queer couples who cannot marry under the current legal regime. The state has an obligation to recognise such unions and grant them benefit under law,” the CJI further stated.

Justice Kaul, in a section titled ‘Equal rights to equal love’, asserted that “the principle of equality mandates that non-heterosexual unions are not excluded from the mainstream socio-political framework”.

Having recognised this right to form unions as a feature of Articles 19 (freedom of speech and expression) and 21 (protection of life and personal liberty) of the Constitution, both judges then took on board the statement of Solicitor General Tushar Mehta to constitute a committee to set out the scope of benefits available to such unions.

In doing so, the CJI recognised “the duty of the State to recognise the entitlements flowing from exercising the right to choose a life partner”.

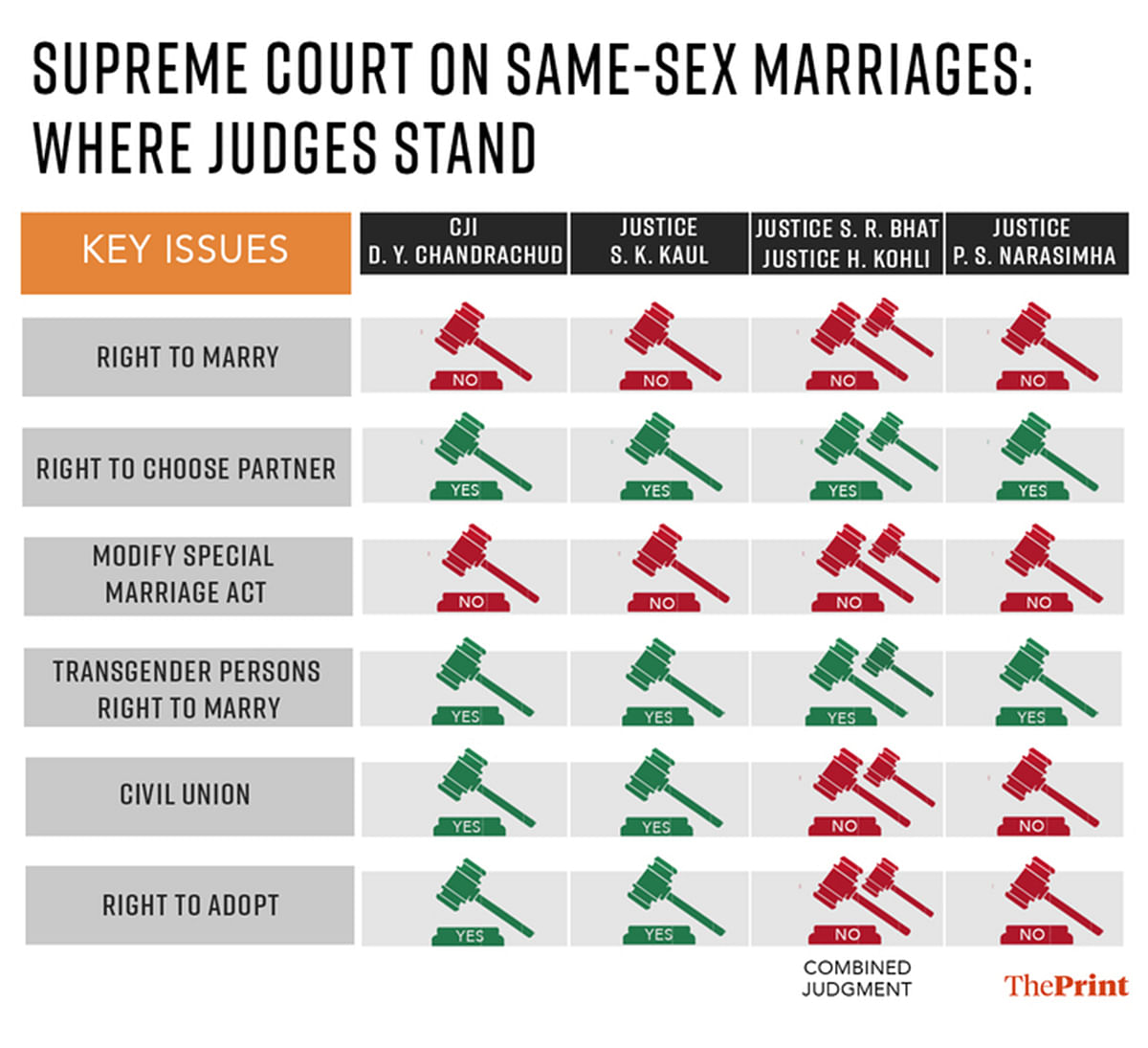

The five-judge bench deciding the case included Justices Ravindra Bhat, Hima Kohli and P.S. Narasimha, apart from Chandrachud and Kaul.

In its verdict, the bench unanimously refused to tweak the Special Marriage Act (SMA) to legalise same-sex marriages and left it to Parliament to decide the matter. Justices Bhat, Kohli and Narasimha turned down the petitioners’ claim to recognise a civil union, leaving the CJI and Justice Kaul in the minority regarding their views on the subject.

The two judges also favoured granting adoption rights to queer and unmarried couples, observing: “There is no material on record to prove the claim that only a married heterosexual couple would be able to provide stability to the child.”

The CJI joined the majority in opining that the SC could not strike down the SMA as unconstitutional or read words into the Act, because this would amount to “judicial legislation”.

Additionally, the judges unanimously held that transgender persons in heterosexual relationships have the right to marry under existing law, including personal laws which regulate marriage.

Also Read: 53% of Indians are accepting of same-sex marriages, finds global survey by Pew Research

‘Right to form intimate associations’

The CJI asserted that the Constitution does not expressly recognise a fundamental right to marry. “However, several facets of the marital relationship are reflections of constitutional values, including the right to human dignity and the right to life and personal liberty,” he added.

He spoke of the right “to form intimate associations”, and observed: “The freedom to choose a partner and the freedom to enjoy their society which are essential components of the right to enter into a union (and the freedom of intimate association) would be rendered otiose if the relationship were to be discriminated against. For the right to have real meaning, the State must recognise a bouquet of entitlements which flow from an abiding relationship of this kind.”

Failure to recognise such entitlements would result in systemic discrimination against queer couples, the CJI asserted.

He further opined that the right to enter into a union was also grounded in Article 19(1)(e) of the Constitution, which talks about the right to reside and settle in any part of India.

He also felt that “preventing members of the LGBTQ community from entering into a union also has the result of denying (in effect) the validity of their sexuality because their sexuality is the reason for such denial”.

This, he said, would also violate the right to autonomy which extends to choosing a gender identity and sexual orientation.

The CJI asserted that the right to enter into a union cannot be restricted based on sexual orientation. Such a restriction, he said, will be violative of Article 15 (which forbids discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, gender or place of birth) of the Constitution.

Supporting the CJI’s opinion, Justice Kaul asserted that “non-heterosexual unions and heterosexual unions/marriages ought to be considered as two sides of the same coin, both in terms of recognition and consequential benefits”.

Same-sex marriages & adoption rights

On the point of adoption, the CJI ruled that unmarried couples and queer couples should be allowed to jointly adopt a child.

In doing so, he ruled that Regulation 5(3) of the Adoption Regulations was ultra vires the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, and Articles 14 (equality before law) and 15 of the Constitution.

Regulation 5 of the Adoption Regulations notified by the Ministry of Women and Child Development and framed by the Central Adoption Resource Authority prescribes the eligibility criteria for prospective adoptive parents.

Regulation 5(3) says that “no child shall be given in adoption to a couple unless they have at least two years of stable marital relationship except in the cases of relative or step-parent adoption”.

“The law cannot make an assumption about good and bad parenting based on the sexuality of individuals. Such an assumption perpetuates a stereotype based on sexuality (that only heterosexuals are good parents and all other parents are bad parents) which is prohibited by Article 15 of the Constitution,” the CJI observed.

The CJI recorded the assurance of the Solicitor General that the central government will constitute a committee chaired by the cabinet secretary for the purpose of defining and elucidating the scope of the entitlements of queer couples who are in unions.

He said that the committee shall include experts with domain knowledge and experience in dealing with the social, psychological, and emotional needs of persons belonging to the queer community as well as members of the queer community.

As for the committee, the CJI opined that it shall consider enabling partners in a queer relationship (i) to be treated as part of the same family for the purposes of a ration card; and (ii) to have the facility of a joint bank account with the option to name the partner as a nominee, in case of death.

He also asked for the committee to consider jail visitation rights and the right to access the body of the deceased partner and arrange the last rites, among other things.

He further asked for the committee to look into legal consequences such as succession rights, maintenance, financial benefits such as under the Income Tax Act, 1961, rights flowing from employment such as gratuity, and family pension and insurance.

Hotline, safe houses

The CJI issued several directions to obviate discrimination against the queer community.

These included directions to the central government, state governments and the Union Territory administration to take steps to sensitise the public about queer identity, including that it is natural and not a mental disorder.

He also called for establishment of hotline numbers that members of the queer community can contact when they face harassment and violence in any form, and establishment and publicising the availability of “safe houses” or Garima Grehs in all districts to provide shelter to members of the community facing violence or discrimination.

“Ensure that ‘treatments’ offered by doctors or other persons, which aim to change gender identity or sexual orientation, are ceased with immediate effect,” the CJI ordered.

He also issued directions to the police machinery. These included instructions that there shall be no harassment of queer couples by summoning them to the police station or visiting their places of residence solely to interrogate them about their gender identity or sexual orientation.

He further directed that when a police complaint is filed apprehending violence from the family for the reason that the complainant is queer or is in a queer relationship, they (police) shall ensure due protection on verifying the genuineness of the complaint.

‘Queerness is not elite’

In his opinion, Justice Chandrachud began with noting that despite decriminalisation of queer relationships and the broad sweep of the Navtej Singh Johar verdict, “members of the queer community still face violence and oppression, contempt, and ridicule in various forms, subtle and not so subtle, every single day”.

The state “has done little to emancipate the community from the shackles of oppression”, he observed.

The CJI also looked at whether “queerness is un-Indian”, in view of the submission by the respondent authorities that homosexuality or gender queerness is not native to India.

Negating this assertion, he observed: “Gender queerness, transgenderism, homosexuality, and queer sexual orientations are natural, age-old phenomena which have historically been present in India. They have not been ‘imported’ from the ‘west’. Moreover, if queerness is natural (which it is), it is by definition impossible for it to be borrowed from another culture or be an imitation of another culture.”

The Centre had contended in court that homosexuality and queer gender identities or transgenderism were predominantly present in urban areas and among the elite sections of society. However, the CJI looked at the petitioners in the case to illustrate the point that queerness was neither urban nor elite.

In his opinion, the CJI asserted that “queerness is a natural phenomenon known to India since ancient times”, and that “it is not urban or elite”.

He further observed: “People may be queer regardless of whether they are from villages, small towns, or semi-urban and urban spaces. Similarly, they may be queer regardless of their caste and economic location.”

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: SC cautious with same-sex marriages case. Keeping personal laws out is in state’s interest