New Delhi: Historically, marriage has been a union solemnised according to customs or personal laws, and its existence is regardless of the State, which can accommodate but not abolish it, held three out of five judges of the Supreme Court that Tuesday ruled out legalizing same-sex marriages in India.

A five-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud declared that the court cannot tweak or read into the Special Marriage Act (SMA) — a secular law governing inter-faith marriages — to grant legal recognition to marriages between queer couples. It left it to Parliament to frame a law for extending institutional acknowledgement to such relationships, adding the current legal framework does not support such a union.

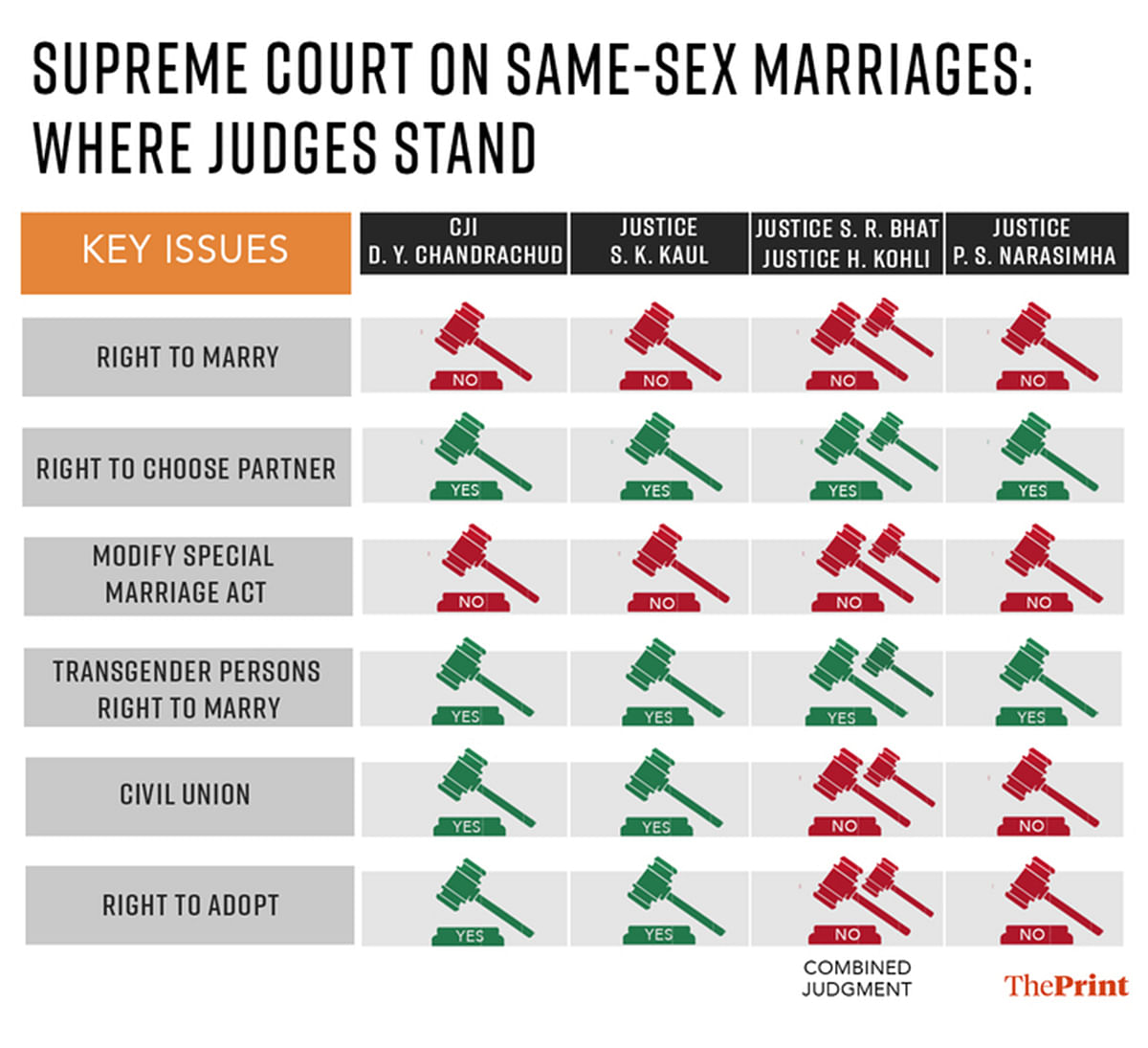

The bench unanimously rejected the central government’s submission that queerness is an “urban and elitist concept”. However, by 3:2 majority, the court ruled out a civil union for such couples.

While Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul sided with CJI Chandrachud in holding that queer couples’ right to enter into a civil union flowed from Part-III of the Constitution, which deals with Fundamental Rights, the other three judges on the bench — Justices S. Ravindra Bhat, Hima Kohli, and P.S. Narasimha — disagreed with them.

The three also gave a divergent opinion regarding another significant issue raised by the petitioners, who demanded institutional recognition of same-sex marriages. In the majority view, the three judges denied queer couples adoption rights as well, opining the minority decision by CJI and Justice Kaul would have “disastrous outcomes”.

While Justice Bhat authored a view that spoke for himself and Justice Kohli, Justice Narasimha penned an 11-page concurring one to supplement their conclusions.

There was consensus amongst all five on the issue of the right to choose a life partner.

They reiterated earlier Supreme Court pronouncements to say that every individual has the right to live with a person of his or her own choice and that State is bound to protect couples who exercise this right of theirs. Further, the bench also said that even state governments can create a legal framework to grant legal recognition to same-sex marriages without waiting for the central government to take a call on this.

Justices Bhat, Kohli and Narasimha also agreed with CJI Chandrachud and Justice Kaul that the right to marry is not a fundamental right, but is a statutory right. However, the right to cohabit and live in a relationship in the privacy of one’s home is fundamental and enjoyed by all.

“The court must exercise restraint and defer to the wisdom of the other branches of the State, which can undertake wide-scale public consultation, consensus building and reflect the will of the people, and be in their best interest,” the three opined.

However, if a law, enacted following the consultation process, undermines or violates the constitutionally protected rights of an individual or a group — no matter how minuscule — their right to seek redressal from the top court is guaranteed under Article 32, they said.

Ordering a social institution or rearranging social structures by creating an entirely new kind of parallel framework for queer couples would require a conception of an entirely different code a new universe of rights and obligations, the judges said.

“This will entail fashioning a regime of state registration of marriage between queer couples, conditions for a valid matrimonial relationship amongst them, spelling out eligibility conditions such as minimum age, relationships which fall within prohibited degrees, grounds for divorce alimony, etc.,” they said.

‘Creating an institution not in court’s remit’

The majority view traversed the brief history of social intervention in social practices, including relation to marriage, and held that legislative activities in this realm aimed at “bringing about gender parity”.

For a long period in societies, the choice of matrimony was not free and bound by social constraints, it said, adding that marriage was seen as an institution meant for procreation and a sexual union of spouses in society that had cast roles for them, with men controlling most decisions.

However, with time, Parliament donned the role of reformers to further the express provisions of the Constitution with regard to equality rights.

Hence, marriage has historically been a union solemnised according to customs or personal laws tracing its origin to religious texts, said Justices Bhat, Kohli, and Narasimha, while noting the diverse customary practices prevalent in India for marriages.

“Marriage customs varied within the Hindu community as well, with many tribal groups in the country not conforming to the practices outlined in the Hindu Marriage Act (HMA).”

Personal laws on marriage codified traditions and customs, which existed, and to an extent regulated these unions. Codification introduced restrictions to further an orderly society or to protect women and children, the majority view added.

“It introduced a minimum age for marriage, eliminated child marriages, and added a list of prohibited degrees of relationships in HMA.”

But the reforms did not cover all fields such as inheritance and succession where unwritten codified laws continue to be enforced. Yet, legislative interventions have been a result of the state’s interest in furthering the interests of given communities or persons, the view said.

It is for this reason that the three judges did not subscribe to the CJI and Justice Kaul’s view that there should be “democratization of intimate zones”.

On the petitioners’ demand, the three judges said civil marriage or recognition of any such relationship with such status cannot exist in the absence of any statute. And through the agency of the court, they want to compel the state to create an institution, which, the court held, is not within its remit.

If indeed there is a right to marry, the three added, the same cannot be operationalised because it is not akin to certain rights under some provisions of the Constitution that cast a positive obligation on the State to ensure they are enforced.

“In our considered opinion this is not one such case where a court can make (a) departure from such a rule and require the state to create social and legal status,” they said.

The majority view also traced the rights enjoyed by queer persons and ruled that a person’s autonomy to choose a spouse or life partner is integral to one’s fundamental right to live with dignity, which is a dimension of equality and all “our liberties”.

“Consensual queer relationships are not criminalised; their right to live their lives, and exercise choice of sexual partners has been recognised. They are no longer to be treated as “sub-par humans” by law,” the view said, taking cognizance of previous Supreme Court decisions from where these rights have flown.

On Special Marriage Act

Justices Bhat, Kohli and Narasimha also called for a closer look at CJI and Justice Kaul’s view that lack of recognition of entitlements flowing from a union, other than marriage, results in the deprivation of certain rights. They said when the law is silent on this issue and leaves parties to express choice, the Constitution does not oblige the state to enact or frame a regulation to enable the facilitation of that expression.

While acknowledging the concerns of the LGBTQ+ community with respect to the denial of access to certain benefits and privileges, the three judges felt that a review of the “impact of legislative framework on the flow of such benefits requires a deliberative and consultative exercise,” for which the “legislature and executive are constitutionally suited, and tasked to undertake”.

“The general statutory scheme for the flow of benefits gratuitous or earned; property or compensation; leave or compassionate appointment, proceed on a certain definitional understanding of partner, dependent, caregiver, and family,” the majority view held.

In that definitional understanding, it is no doubt true that certain classes of individuals, same-sex partners, live-in relationships, and non-intimate caregivers including siblings are left out, it said.

“The impact of some of these definitions is iniquitous and in some cases discriminatory. The policy considerations and legislative frameworks underlying these definitional contexts are too diverse to be captured and evaluated within a singular judicial proceeding,” the majority view held.

The challenge to the SMA on grounds of impermissible classification was not entertained by the three judges. They further refused to accept the petitioners’ argument that the act had lost its relevance as it operated in a discriminatory manner.

“The Statement of Objects and Reasons of SMA clearly suggests that the sole reason for the enactment of the Act was to replace the earlier colonial era law and provide for certain new provisions; it does not refer to any specific object sought to be achieved or the reasons that necessitated the enactment of the new Act other than that it was meant to facilitate marriage between persons professing different faiths,” stated the majority view.

The law’s sole intention was to enable marriage (as it was understood then, that is for heterosexual couples) of persons professing or belonging to different faiths, an option hitherto available, subject to various limitations, the majority view said.

“There was no idea to exclude non-heterosexual couples, because at that time, even consensual physical intimacy of such persons, was outlawed by Section 377 IPC. So, while the Act sought to provide an avenue for those marriages that did not enjoy support in society, or did not have the benefit of custom to solemnise, it would be quite a stretch to say that this included same-sex marriages,” the three judges said.

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: SC refuses to tweak Special Marriage Act to legalise same-sex unions, says Parliament will decide