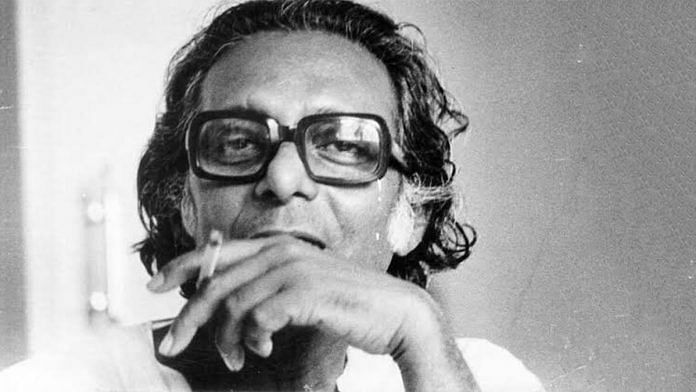

New Delhi: For any film aficionado, watching Mrinal Sen’s movies is a must.

Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of the 20th century, Mrinal Sen started the New Cinema movement in Bengal, and eventually in India, with his raw, dark and provocative films. Sen had received national and international accolades for his movies, but he was also disliked by many for his stringent ideals.

In his 60-year career, Sen made close to 30 feature films and documentaries. On his 96th birth anniversary on 14 May, ThePrint recounts Sen’s life, his filmmaking and some of his most memorable works.

Early life

Born on 14 May 1923 in Bangladesh, Sen grew up aspiring to study physics although he did have interest in films. In one of his last interviews, he remembers Charlie Chaplin as one of his earliest inspirations.

“I had no interest in cinema but I had to see films. One of the first films I saw was the Charlie Chaplin starrer The Kid (1921). I was eight or nine years old at the time. I loved it! I laughed and laughed. Then I saw all of Chaplin in a festival where my film Calcutta 71 was being screened, it was in Venice. Chaplin was being presented the Lifetime Achievement Award and I wanted to tell him that I became wise after watching his films,” he had said.

Sen moved to Kolkata as a teenager. While in college in the late 1930s, he joined the cultural wing of the CPI and was thus introduced to the world of theatre and film.

However, it was not until he came across a book on film aesthetics much later that his interest in film and filmmaking was truly piqued. To earn a living, Sen took up a job as a medical representative outside Kolkata. But, he soon quit and moved back to Kolkata in the 1940s to pursue his dreams of making films.

Baishey Shravan and Bhuvan Shome

Mrinal Sen’s first two films — Raat Bhore (1955), Neel Akasher Neechey (1958) — didn’t do well. The latter was also the first film to be banned in independent India for its deeply political overtones.

It was Sen’s third film Baishey Shravan (1960) that put him on the international map. The story was set in the backdrop of World War II when West Bengal was going through one of the worst famines ever known. The film showed a poor couple struggling to sustain themselves without food. The story documented the change in their relationship as they managed various difficulties and the dark side of human nature in the face of a calamity. It was the first Mrinal Sen film to be sent to a foreign film festival — the London Film Festival.

In 1969, Sen’s Bhuvan Shome released and that made people notice him as a force to be reckoned with as it won him three national awards — for best director, best actor (Utpal Dutt), and best film.

The film was made on a shoe-string budget provided by the central government. Starring a very young Dutt and Suhasini Mulay, the story revolved around a young, successful railway officer who has everything, but is very lonely. He then meets a young woman while on a hunting trip, who ends up teaching him more about hunting and also life.

Criticised for making dark movies

Sen is known to be a part of the troika of Bengali parallel cinema along with his contemporaries and treasured filmmakers Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak. The three filmmakers have made some of the best films that India has ever seen, and were friends, too, who had a healthy competition between them.

Even today, ardent fans of Sen and Ray debate whose films are better. While Ray was more popular as his films underlined hope, love and closure, Sen chose stories that were dark, depressing, deeply political and abrupt.

On the highly political nature of his films, Sen had once said, “I don’t agree with Godard when he says that the cinema is a gun. That is too romantic an expression. You can’t topple a government or a system by making one ‘Potemkin’. You can’t do that with ten ‘Potemkins’. All you can do is create an environment in which you can discuss a society that is growing undemocratic, fascistic.”

His films were often criticised for having no proper or happy endings, and that they dwelt too much on human suffering. But, this obviously did not stop him from being a favourite with actors and audiences alike.

Sen’s wife his most trusted collaborator

Sen had a collaborator whom he trusted implicitly with his filmmaking process — his wife and actor, Gita Sen. She would usually star in Sen’s films, and would often give him advice on certain scenes and scripts. She was also popular with the actors and the crew.

According to director Shyam Benegal, “Gita di had a way of making people feel comfortable. She was also an incredible actress who had an innate understanding of the craft. And Mrinal da was her most persistent fan”.

Their son, Kunal Sen, also fondly remembers his parents collaborating on films. “Theirs was a marriage of true intellectual equals. Had a strong influence on the dialogues in my father’s films. While writing a script, he would often read a scene or two to us, and my mother would be very critical any time she sensed something didn’t sound adequately natural. This is where her experience as an actress helped. Even during shootings, she had a much keener eye towards the everyday details of a middle class Bengali household, and she would help in everything starting from set design to acting and dialogues. They both had tremendous respect towards each other. My father was very lonely since my mother died a couple of years ago,” he said.

Films on Calcutta

Like so many Bengali filmmakers, Sen, too, dedicated a lot of his films to the city of Calcutta (now Kolkata). He made a famous Calcutta trilogy — Interview (1971), Calcutta 71 (1972), and Padatik (1973) — which are considered to be some of the finest films ever made on the city as they didn’t look at its stereotypical aspects. They, instead, forced the audience to think about the real issues such as poverty, famine, unemployment that plagued the ‘City of Joy’.

Sen also made films in Odiya, and one in Telugu (Oka Oori Katha), which were equally acclaimed. Ray, after watching Oka Oori Katha even admitted that he was jealous of Sen as he proved to be a better filmmaker.

Sen also made several documentaries and short films that had permanent places in most international festivals. He received much criticism for his staunch Marxist ideals, which he unabashedly showed in his films, but he was honoured with countless awards too – a Padma Bhushan, multiple national awards, the Nehru Soviet Land Award, the Commandeur de Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, multiple honorary degrees, and was even inducted into the Oscar Academy as a member.

Sen passed away on 30 December 2018 at the age of 95. His strong, unwavering voice will forever be heard through his films. During the shoot of his last film Amar Bhuvan in 2002, when he spoke about his filmmaking process, Sen had said: “After I make a film, I feel like collapsing but then I wake up again”.

Also read: Saadat Hasan Manto, lover of fountain pens, shoes & alcohol, who was the voice of Partition