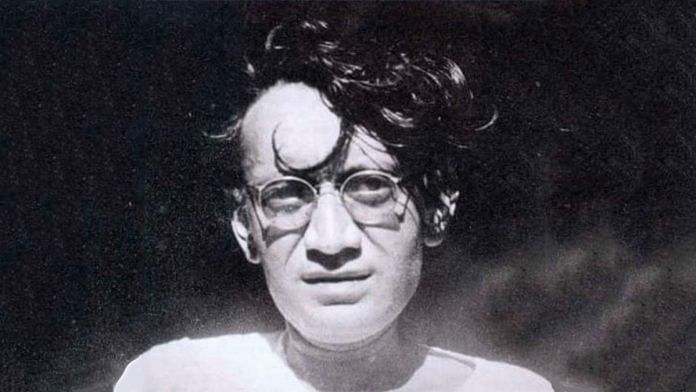

New Delhi: “Here lies Saadat Hasan Manto. With him lie buried all the arts and mysteries of short story writing. Under tons of earth he lies, wondering if he is a greater short story writer than God,” reads one of the world’s most accomplished short story writer’s self-chosen epitaph.

A cognoscente of the human condition, Saadat Hasan Manto’s understanding of society, morality and ethics translated into a narrative of psychoanalytical portraits that often described the divided selves borne out of the 1947 India-Pakistan Partition.

“Whether he was writing about prostitutes, pimps, or criminals, Manto wanted to impress on his readers that these disreputable people were also human, much more so than those who cloaked their failings in a thick veil of hypocrisy,” wrote Ayesha Jalal in The Pity of Partition — Manto’s Life, Times, and Work across the India–Pakistan Divide.

The corpus of Manto’s writings is often autobiographical and reflects his own divided self. On his 107th birth anniversary on 11 May, ThePrint recounts Manto’s life and some of his crucial works.

Manto, the rebel

Manto was born in Ludhiana in British India on 11 May 1912 to a Kashmiri Muslim family. From the outset, Manto’s life was a series of complications.

Manto’s mother, Sardar Begum, was the second wife of his father Khwaja Ghulam Hasan. His father, a sessions judge in the government of Punjab’s justice department, had spent a considerable time in educating the children of his first wife and thus had little time for Manto and his sister.

The sidelining of Manto’s mother and Hasan’s stern approach towards Manto are often perceived to be the reason behind Manto growing up to be a rebel.

“Manto was fiercely individualistic and self-confident. If these traits can be credited to the indulgence of a doting mother and sister, the steely discipline of an authoritarian father served as a catalyst for Saadat’s rebellious nature,” wrote Jalal.

Manto studied briefly in Aligarh Muslim University after which he moved to Bombay in 1936 as the editor of a weekly film magazine Musawwir (painter) and also wrote screenplays for movies. He earned Rs 40 a month as the editor and “whatever little was left of his modest salary, he burned up on drink, expensive fountain pens, and his fetish for shoes, which he liked collecting and giving away as presents to friends and relatives”, Jalal wrote.

In 1948, after Partition, Manto moved to Lahore.

“My name is Saadat Hasan Manto and I was born in a place that is now in India. My mother is buried there. My father is buried there. My first-born is also resting in that bit of earth,” Manto wrote in one of his iconic Letters to Uncle Sam.

“However, that place is no longer my country. My country now is Pakistan which I had only seen five or six times before as a British subject,” he wrote.

Manto’s sentiment finds echo in his short stories Toba Tek Singh, where the protagonist finds himself without a place to call home, and Tetwal ka Kutta, where the dog is murdered mercilessly along the India-Pakistan border since neither of the country claimed him.

His love for alcohol

Manto would apparently sit at some cafe in Bombay to only write so that he could earn enough to get to the local distillery and buy himself alcohol.

“If a piece of mine appears in a newspaper and I earn twenty to twenty-five rupees at the rate of seven rupees a column, I hire a tonga and go buy locally distilled whiskey,” he wrote in the Letters to Uncle Sam.

Also read: Nandita Das’ Manto is a befitting reply to Sunny Deol’s Gadar-like jingoism

His works

Manto was far ahead of his time and as such courted controversy in his short but prolific career. He faced several court cases both in India and Pakistan for ‘obscenity and pornographic content’ in his writings.

The five short stories for which Manto was tried were Kali Shalvar, Dhooan, Boo, Thanda Ghosht and Upar, Niche Aur Darmiyan.

Manto penned his experience of his trial in Upar, Niche Aur Darmiyan in an evocative piece called the Fifth Trial.

After being fined Rs 25, the judge said to him, “Manto sahib, I consider you a great short-story writer of our time. The reason I wanted to get together with you was that I didn’t wish you to go back thinking that I am not an admirer.”

Manto then asked: “If you’re an admirer, sir, then why did you fine me?” The judge smiled and replied: “Why? I’ll give you my answer after a year.”

Manto courted controversy for talking about prostitutes in Kali Shalvar. In Boo and Thanda Ghosht, he talked about sexual perversions like necrophilia. Most of his short stories asserted that Partition had brought out the worst in people.

On Partition

In one of his earliest works, A Tale of 1947, Manto wrote about the grim reality of Partition.

“…the Hindus who murdered one hundred thousand Muslims may rejoice at the death of Islam when actually Islam has not been affected in the least bit. Those who think religion can be hunted down with guns are stupid. Religion, faith, belief, devotion are matters of the spirit, not of the body. Knives, daggers, and bullets cannot destroy religion,” he wrote.

Manto’s short stories such as Khol Do, Sonarel, Mozail, Sarkando Ke Peeche, Toba Tek Singh, Tetwal ka Kutta and Aakhri Salute gave him wide acclaim.

In 1955, Manto passed away due to cirrhosis, a liver disease, leaving behind an enduring legacy.

All the excerpts of Manto’s works were taken from Bitter Fruit – The Very Best Of Saadat Hasan Manto with permission from the publisher, Penguin India.

Also read: Manto ban and Modi’s election: What Pakistan’s VIPs told me

It’s great to remember a legend in his own right but the writer has not done justice while conveying Manto’s comments On Partition “Hindus who murdered one hundred thousand Muslims……”. Bcoz the partition has seen butchering of people on both sides….. It seems that he was pained by Qatle-aam of Muslims only…. Whereas the fact is Manto was pained at partition itself ….. I have read Manto extensively but nowhere Manto’s these lines have been highlighted as depicted by you may be for obvious reasons… The writer should have avoided these lines…. That’s injustice to Manto….

No doubt Manto was a great writer, but lets give more credit to millions of Muslims who refused partition and stayed back, where they were born. Manto for all his objections to partition, went away from the land where his near and dear ones were buried. When the push came to the shove Manto developed cold feet, despite being a man of far greater resources and influence, than many of his religious compatriots, who refused to move, despite the dangers.