A future Indian ambassador to the United States, a future law minister, and a renowned jurist huddled on a warm June afternoon in the gothic Bombay High Court building in 1957. Surrounded by sculptures of wolves and foxes, they were there to decide whether one of India’s oldest corporates, a Tata company, could donate money to the Congress party. Everybody in the court that day saw the “danger” in allowing companies to contribute funds to political parties.

They were there courtesy a vigilant shareholder of the company, Jayantilal Ranchhoddas Koticha, who smelled a rat when the Tata Iron and Steel Co. Ltd. (TISCO) amended its Memorandum of Association, especially to allow the company to donate to political institutions. Koticha’s Lawyer H.R. Gokhale argued that permitting companies to contribute funds to a political party is nothing short of buying over the party. But the court ruled in TISCO’s favor, stating that “it is primarily for the company to decide what is for its good”.

A year later, Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court Justice M.C. Chagla, who had delivered the judgment, retired and was almost immediately appointed as ambassador by the Nehru government to the United States. Gokhale went on to serve as the law minister in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet during the Emergency. But the questions they posed inside that gothic building still haunts India’s lawmakers and voters.

The political funding debate in India is today synonymous with electoral bonds, the money channel that has remained in controversy ever since its introduction in 2017-2018. And with the Supreme Court reserving its judgment on the validity of these bonds, this debate will move forward. At least that’s what the top court’s observations reveal, with CJI DY Chandrachud underlining that “the scheme provides selective anonymity.”

Also read: Rabinder Singh spy scandal exposed R&AW’s ugly sides. But India hasn’t learned from its mistakes

The case that set them all free

In the TISCO case, the company’s stand was clear. It said that Congress’ industrial policy was simply better, and that the future of the steel industry largely depended on the government’s industrial policy. But TISCO was careful. It said that Congress had already decided the policy, and so, it wants to contribute to the party only to keep it in power, not to influence or mould that policy.

Gokhale was concerned that if this was allowed, it would be impossible to get the party, which is elected with the help of such funds, to determine policies in the interests of the country, socialism, or democracy.

H.M. Seervai, who was appearing for TISCO, also told the court that he understands the dangers of such a power being given to a larger powerful wealthy corporation in a democracy, but said that the legislature should decide how this power needs to be tamed.

And thus began the story of a question that then Chief Justice M.C. Chagla asked in court that day — “How is anyone to say that at what point the contribution ceases to merely keep the party in power and begins to influence its policy[?]”

But even in 1950s, the concerns weren’t new by any measure. Before Independence, B.R. Ambedkar spoke of both Mahatma Gandhi and Mohammed Ali Jinnah in the same scathing tone, saying that “in establishing their supremacy, they have taken the aid of big business and money magnates”.

“For the first time in our country, money is taking the field as an organized player,” he said in Pune in 1943. Decades later, former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was concerned that jantantra (democracy) was degenerating into dhantantra (oligarchy of the rich).

“This is not good for the country,” he declared back in 2004.

How is anyone to say that at what point the contribution ceases to merely keep the party in power and begins to influence its policy[?]

–Bombay High Court Chief Justice M.C. Chagla, in the 1957 Cisco case

Also read: 1967 was the year politics changed. Modi wants to go back to the simpler times before that

Finding the fix

Electoral bonds have done what past innovations in party funding couldn’t — they have sprung the issue onto the national stage, delivering it straight to the living room discussions.

Petitions challenging the amendments and the electoral bonds scheme were filed in the Supreme Court back in 2017 and 2018. The matter, however, remained pending for six years during which six Chief Justices took office. When the matter was finally heard by the top Court this year, it wrapped up the hearing and reserved its judgment within six sessions, over a period of three days.

The pendulum of the court judgment could swing either side, any minute. However, none of the outcomes would completely fix the issues that plague party funding in India — with or without electoral bonds.

According to Aradhya Sethia, PhD candidate at Cambridge University, for political funding reforms, it has to become an electorally important issue.

“There is no other way. I do not think the Supreme Court, more than maybe striking down a few laws, etc, can and design a very complex piece of regulation…It would be too difficult for the court to articulate a reform proposal without any involvement of the Election Commission or political parties themselves,” Sethia told ThePrint.

Also read: Duties, duties, duties. Modi is going back to the Indira Gandhi Emergency era

The elections that changed it all

The loss of elections in 1967 in nine states came as a rude shock to the Congress and Indira Gandhi. While the Congress party won at the national level, it was exposed as weak for the first time. It triggered the end of simultaneous elections, and the start of coalition politics. However, the loss did more than just bring change in the country’s election cycles.

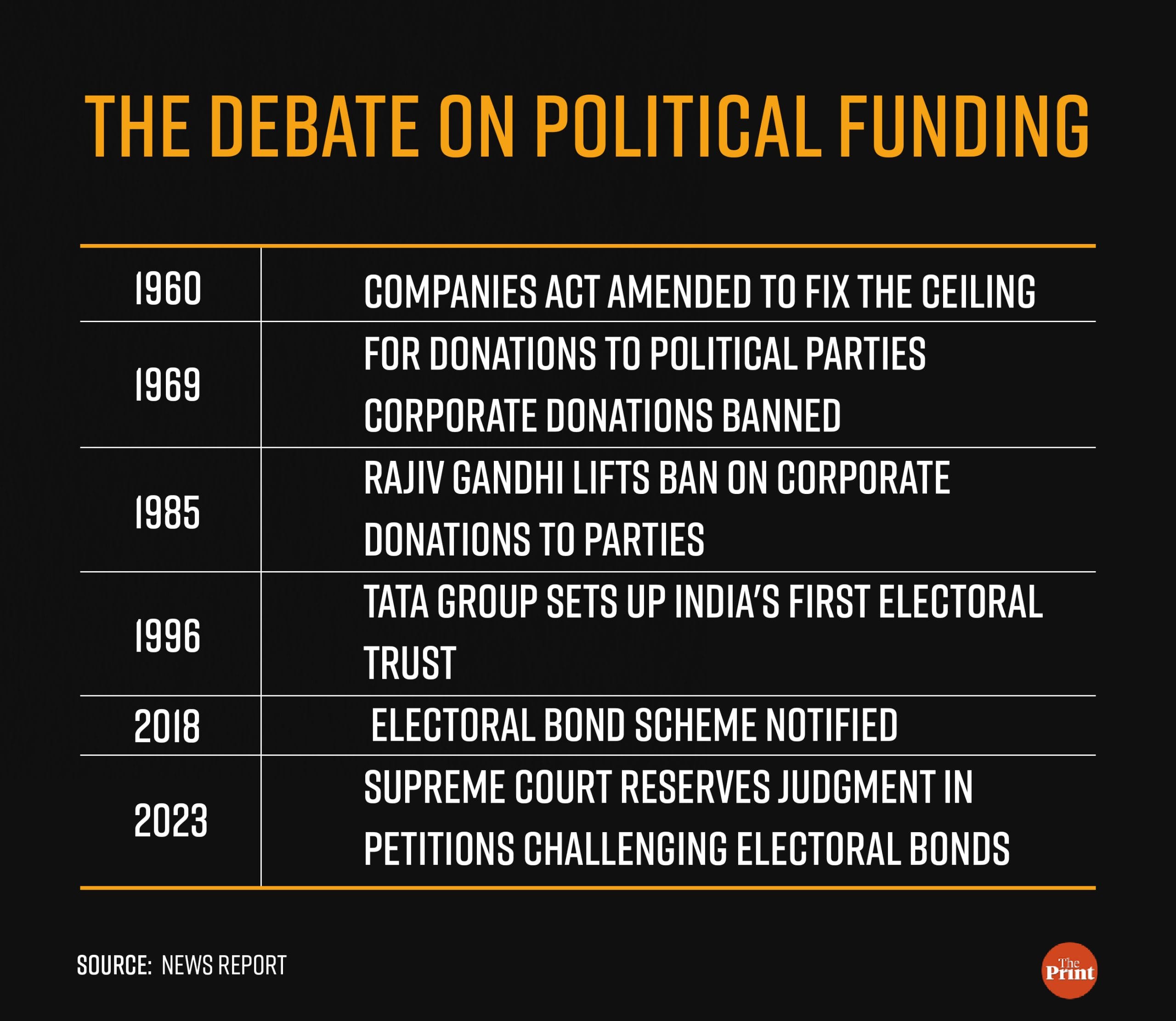

And thus came a key turning point in the history of political financing in India, when Indira Gandhi banned corporate donations to political parties in 1969. Before this ban, the Companies Act fixed the ceiling for donations to political parties at Rs 25,000 or five per cent of the average net profit of the company for the three preceding financial years, whichever amount was greater. The contributions had to be authorised by the Memorandum of Association of the companies, and these donations had to be disclosed in its accounts.

The ban was backed by the report submitted by the Santhanam Committee in 1964, on prevention of corruption. It had suggested that “companies should not be allowed to participate in politics through their donations.”

However, according to Milan Vaishnav, Director of the South Asia Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the ban was a “politically inspired maneuver” because Indira Gandhi was looking at rising opposition parties – the Jan Sangh and the Swatantra Party– who had accumulated capital from many corporations.

Indira Gandhi banned corporate donations to political parties in 1969. Before this ban, the Companies Act fixed the ceiling for donations to political parties at Rs 25,000 or five per cent of the average net profit of the company for the three preceding financial years, whichever amount was greater.

Almost simultaneously, Gandhi also began to tighten government control over the private sector. In a midnight declaration on 19 July 1969, her government nationalised 14 banks, each with reserves of more than Rs 50 crore. This was followed by nationalisation of coal mines, petroleum, and general insurance in the early 1970s. Add to this a string of laws including the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act 1969, which intensified regulation of big business, and the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA) 1973, which tightly controlled foreign investors.

The result was a deadly soup of opportunity for black money and politics to join hands. The tightened government control over the private sector provided an easy fix for the ban — donations in exchange for regulatory and allocative favors. Vaishnav asserts that this “drove political finance completely underground”.

“The stage was set that if you were a private company and you wanted to do anything in India, there was a licence or a permit or a clearance you needed. And that created a quid pro quo for bureaucrats and the politicians to trade those permissions in exchange for campaign contributions,” says Vaishnav.

Also read: When Indira Gandhi nationalised foodgrain and failed — a disaster and a cautionary tale

An ‘unpublished’ brochure

The politics of the 70s ensured money flew into politics in creative ways.

For instance, Calcutta-based Dalpat Rai Mehta had just become a shareholder in Graphite India Ltd. in late 1977 when he looked at the annual reports and accounts of the company. While everything seemed to be in order, one entry piqued his interest – an expenditure of Rs 1,52,000 incurred for advertisements in the All India Congress Committee Souvenirs.

A little digging told him that the souvenirs, which were brochures sponsored by the Congress party, didn’t even see the light of the day. He approached a magistrate court in Calcutta, alleging that the company was violating Section 293A of the Companies Act by contributing to a political party. Mehta even saw some success when the magistrate court took cognizance of the complaint and issued summons.

However, his luck ran out when the company approached the Calcutta High Court. In the high court, Mehta stood alone against the company, representing himself in a courtroom of the majestic high court building. And he was not just facing the company, but also the Left Front state government, which supported the company’s case.

The court ruled that an advertisement is not the same as a contribution and quashed the case against the company. And this became one of the ways in which corporations continued to give money to political parties during the ban.

Indira Gandhi’s ban was undone by her son Rajiv Gandhi in 1985, when his relatively liberalizing and pro-business government allowed company donations to political parties.

Also read: Nehru’s Hindu Code Bill vs Modi’s UCC— same script, same drama, different Indias

Rs 19,999: the numbers game

Indira Gandhi’s ban was undone by her son Rajiv Gandhi in 1985, when his relatively liberalizing and pro-business government allowed company donations to political parties.

All private companies were allowed to contribute to political parties or to any person for political purposes, subject to approval by the board of directors, and disclosure in the profit and loss statement. However, in a financial year, a company could not donate more than 5 per cent of its average net profits of the previous three years.

Since 1985, up until electoral bonds, corporate funding to political parties has only seen incremental changes over the years. In 2013, the limit of 5 per cent was increased to 7.5 per cent of the average profit of the previous three years.

However, when push comes to shove, all parties have always managed to find ways through “creative accounting” to bypass disclosure requirements for receiving funds.

The most exploitable of these loopholes has been the Representation of the Peoples Act provision requiring political parties to report only those contributions which exceed Rs 20,000. For such donations, parties have to record the donor’s name, address, PAN number, mode of payment and date of donation. They have to submit an annual report to the Election Commission to claim tax exemption.

If this is not complied with, the party is not entitled to any tax relief under the Income Tax Act, but parties and corporations have historically chosen anonymity over tax benefits. The fix was simple. Break down big donations into smaller packages of Rs 19,999 and avoid disclosure.

And this isn’t a secret. The Law Commission of India, in its 255th report published in 2015, acknowledged this loophole as well. It also cited some staggering numbers–an election expenses analysis for the Lok Sabha 2009 elections showed that more than 75 per cent of parties’ sources are unknown, while donations over Rs 20,000 comprise only 9 per cent of parties’ funding. A more recent analysis by ADR shows that BSP declared that it did not receive any donations above Rs 20,000 during FY22— a claim that it has consistently made for the past 16 years.

Also read: ‘Air India ki flight mat lo’ — how Canadian neglect led up to Kanishka bombing 38 yrs ago

Trust-worthy

This creative accounting method isn’t an isolated innovation within the political funding landscape, which sees both the donors as well as political parties try their hands at bringing in innovations to escape regulation.

In 2013, the government notified the Electoral Trusts Scheme laying down the eligibility and procedure for their registration. However, even now, while an electoral trust has to disclose names of its donors and the amounts donated by them at the end of a financial year to the EC, it is not required to link the donated amounts to any specific political party.

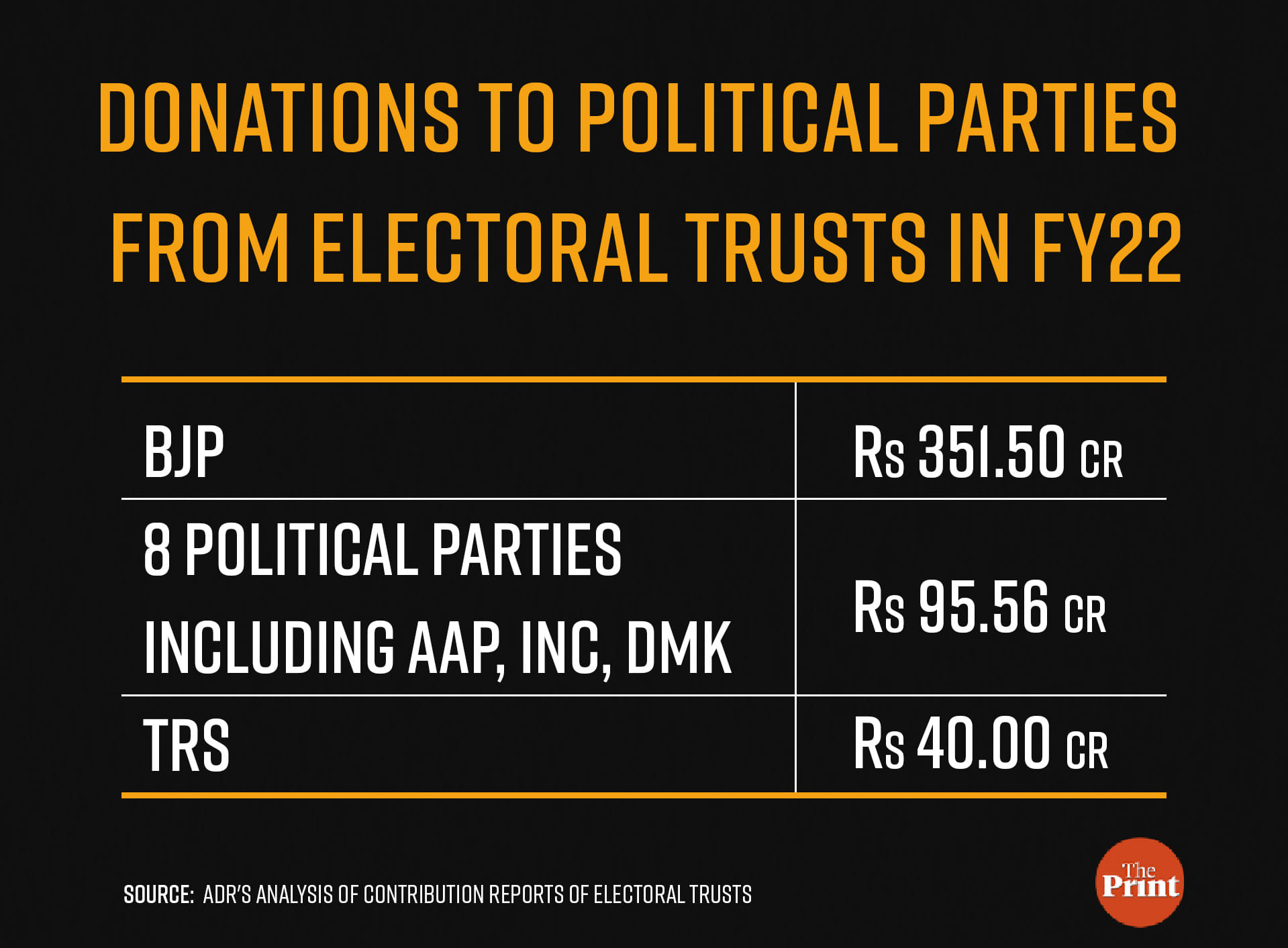

One such innovation is that of electoral trusts. In 1996, Tata Group set up the first such trust— an independent entity that would channel funds from Tata Group companies to political parties without any mention of the original donor company’s name on the balance sheets of the parties. Over the next few years, several companies followed suit, because these trusts also sheltered companies from the scrutiny of their shareholders — who have in the past dragged companies to courts as seen in Koticha and Mehta’s case.

These trusts functioned without any regulatory vacuum for at least two decades before the UPA government made donations to electoral trusts tax-exempt in 2009. ADR’s analysis of data released by EC shows that between 2004-05 and 2011-12, six electoral trusts donated a total amount of Rs 105 crore to national parties.

In 2013, the government notified the Electoral Trusts Scheme laying down the eligibility and procedure for their registration. However, even now, while an electoral trust has to disclose names of its donors and the amounts donated by them at the end of a financial year to the EC, it is not required to link the donated amounts to any specific political party. Similarly, there is a separate requirement for the trusts to specify the aggregate amount distributed to each political party without attributing amounts to specific donors.

So people can know where the funding is coming from only if there is just one contributor and one beneficiary of a particular trust. Take the Janhit Electoral Trust, for instance, which had just one contribution of Rs 2.5 crore in 2018-19 from Vedanta, and the entire amount was donated to the BJP.

Trusts have, therefore, acted as a buffer allowing companies to donate to parties without the accompanying risk of backlash for favoring one over the other. And the shroud of opacity only gets deeper. None of these trusts has a website or publicly listed contact details.

The limited regulation of trusts is also toothless. While the Income Tax Act provides tax relief on donations to electoral trusts, trusts are not required to compulsorily disclose details of funds under the Representation of People Act. Additionally, the only penalty for non-submission of an annual report to the ECI is that “adverse notice shall be taken” of the failure to comply with the instructions.

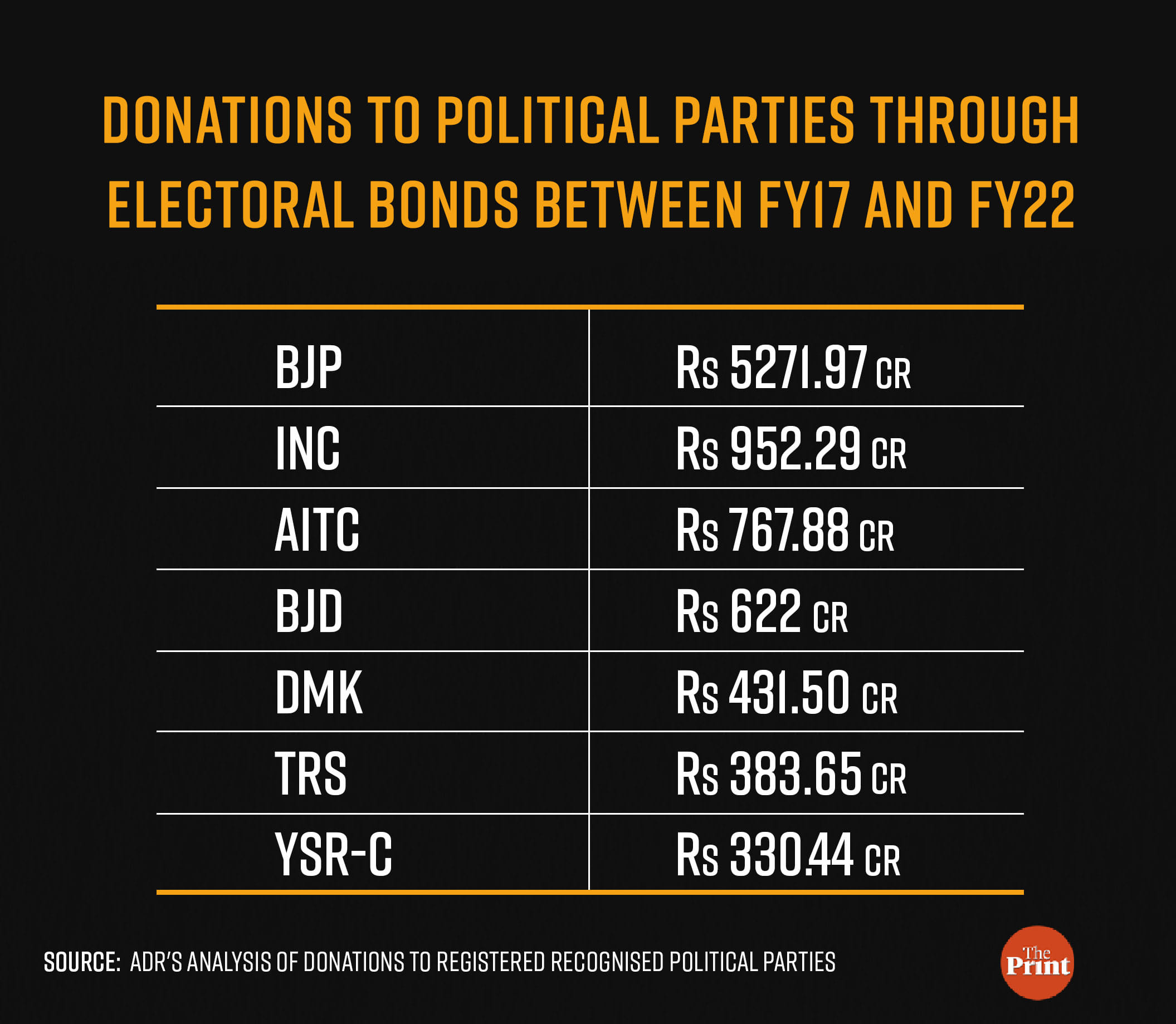

Electoral trusts, therefore, continue to contribute significantly to parties. ADR’s analysis shows that from 2013-14 to 2021-22, BJP got 72 per cent of the total Rs 2,269 crore donated through electoral trusts. As compared to this, Congress received 9.7 per cent of the electoral trust donations in the same period.

Also read: Soviet Midas touch drove Indian economy during Cold War. India rekindling rupee-rouble affair

Enter bond. Electoral bond

In his 2017 budget speech, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley lamented that even 70 years after Independence, the country has not been able to evolve a transparent method of funding political parties, which he said was vital for free and fair elections. Parties, he accepted, continue to receive most of their funds through anonymous donations shown in cash. But he had a ‘solution’ in mind. He pitched electoral bonds as “reform” that will bring about greater transparency and accountability in political funding, while preventing generation of black money.

When launched, the scheme came as a surprise. Former Election Commissioner Ashok Lavasa points out that laws and policies are usually based on a felt demand or an expressed demand made by the stakeholders.

“That’s how laws and policies are made,” says Lavasa asking “who represented to the government, was it done in written form, is there a record available to show that the government was approached by so many people who wanted this amendment (the 2016 and 2017 amendments) to be made,” he told ThePrint.

On 2 January 2018, the government notified the electoral bond scheme.

These bonds are sold in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh, and Rs 1 crore, and can be bought by any Indian citizen or by entities incorporated or established in India. They are only sold by authorised branches of the State Bank of India, and the donor is required to pay the amount through a cheque or a digital mechanism to the authorized SBI branch. Therefore, the transaction leaves behind a banking trail.

However, in the run up to their introduction, the stage had already been set for enclosing these bonds in a cloak of secrecy. In 2016, the government amended the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act 2010 (FCRA) to allow foreign companies with subsidiaries in India to fund political parties in India. Previously, foreign companies were prohibited from donating to political parties under the FCRA.

(On electoral bonds) who represented to the government? Was it done in

written form? Is there a record available to show that the government was approached by so many people who wanted this amendment (the 2016 and 2017 amendments) to be made?

–Ashok Lavasa, former election commissioner

In 2017, the Finance Act also amended several laws. The amendment to the Representation of the People Act 1951 exempts political parties from the requirement of keeping record of the donations received through electoral bonds in their contribution reports to the EC. The government has also removed the limit of 7.5 per cent of the annual profit for companies to make donations to political parties. Individual cash donations have been capped at Rs 2,000.

Read the scheme with these amendments. The result is that political parties are not required to maintain any record of the donations or the names and addresses of donors of these bonds.

Anjali Bhardwaj, co-convener of National Campaign for People’s Right to Information, says that electoral bonds have “legitimized the anonymity of political party fundings” – whether these funds come through cash or through banking channels.

Her statements reveal the harsh truths of this system. The amendments, she says, lead to “opening our elections and making them vulnerable to corporate interest, to crony capitalism and also to foreign interests at the cost of citizens’ welfare and citizen centric policies.”

There was no consultation with the public or political parties before the scheme was launched. In fact, the Narendra Modi government was considering opening up the electoral bond scheme for public consultation before introducing it in 2017. However, the plan was dropped the day Modi was briefed about the scheme, as per file notings accessed by Bhardwaj. The only clue is a line in Jaitley’s speech, that “donors have also expressed reluctance in donating by cheque or other transparent methods as it would disclose their identity and entail adverse consequences.”

“Even if there was a demand, why would the government compromise with the principle of full disclosure for the sake of a handful of potential donors?” Lavasa asks.

Also read: Campa, Coke, Pepsi, politics—cola wars and Indian capitalism. Now Ambani to fuel new battle

Visible in politics

In 2012, two researchers conducted confidential interviews with donors and political fund-raisers over a period of three years from 2008 to 2011, in Delhi Mumbai and Bengaluru.

They found Indian businesses are still vulnerable to discretionary government actions, and government clearances have become pressure points “for extorting payments from businesses”. This is because despite two decades of economic liberalization, permissions such as environmental clearances or land acquisition from central and state authorities are still required when starting, operating or expanding businesses.

The duo also found that businesses prefer being secretive about their donations, and choose anonymity over any tax benefit that they may get by disclosing the donations. Historically, businesses do prefer anonymity, because of the risk of victimization if the party the corporate backs loses the election.

This argument prominently features in the government’s defence of the electoral bonds in the Supreme Court as well, that wants to protect donors from victimization.

New York-based economist Karan Bhasin says this argument holds water, especially in an “imperfect criminal justice system”.

For a small manufacturing unit or a small entrepreneur located in a

particular manufacturing facility, imagine the extent of witch hunt that they

can be subjected to, if their donation is not anonymous

— Karan Bhasin, New York-based economist

He also recalls public attacks on “a particular industrialist” by political leaders. This never happened in the past. In the past, politicians never attacked industrialists so openly.

While Bhasin doesn’t name names, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi does. He has launched a consistent attack on billionaire industrialist Gautam Adani and the PM, accusing the latter of working for the business tycoon “round-the-clock”. The Congress leader has said that “Modi guarantee” means Adani’s government will be formed in 2024.

“For a small manufacturing unit or a small entrepreneur located in a particular manufacturing facility, imagine the extent of witch hunt that they can be subjected to, if their donation is not anonymous,” Bhasin says. He says that if anonymity is removed from the equation, the big business may continue bringing in funds, but it would make the medium and small sized enterprises hesitant from contributing. Therefore, for him, this need for confidentiality trumps the demands for transparency.

“If that transparency can be used to do political witch hunt without tangible recourse to justice, then that transparency will create more problems than offer any solutions,” he says.

However, Sethia says that the argument of protecting donors from victimization does not reflect too well on the parties themselves, pointing out that with this argument, “parties, in some ways, are confessing that they are victimizing businesses.”

Also read: Gandhi spoke no Sanskrit & Narayana Guru spoke no English when they met during Vaikom

‘Not the ultimate solution’

While donations are one aspect of party funding, what they do with those donations and how much money they spend on elections is often overlooked in India.

The Representation of the People Act 1951 imposes statutory limits for expenditure by individual candidates. But the law does not regulate the election expenditure of political parties for propagation of its own agenda.

If you say that whatever you received through electoral bonds can be

spent during elections by political parties, then obviously the issue of

level-playing field arises. This warrants a ceiling on expenditure limits on

political parties for election expenses

–Ashok Lavasa, former election commissioner

Lavasa says that the principle of level-playing field justifies expenditure limits on candidates, and suggests a change in the laws for governing expenditure of political parties during elections as well.

“If you say that whatever you received through electoral bonds can be spent during elections by political parties, then obviously the issue of level-playing field arises. This warrants a ceiling on expenditure limits on political parties for election expenses,” he says.

In the five years since electoral bonds were introduced, numbers also show that these bonds have not created a level-playing field, with the ruling party bagging an overwhelming majority of funds through the instrument. In these five years, more than half, or 57 per cent of the funds extended through bonds have gone to the BJP. While the BJP received Rs 5,271.97 crore via bonds between 2017 and 2022, the Congress was a distant second at Rs 952.29 crore.

However, Gopal Krishna Agarwal, the national spokesperson of BJP still harps on the transparency argument. He says that before these bonds came into the picture, there was complete opaqueness in funding.

“So this is one of the steps towards transparency in funding,” he told ThePrint. He is quick to clarify that electoral bonds cannot be an “ultimate solution to bring complete transparency but it is an important step towards it”. He emphasizes on the usage of banking channels, and the reduction of permissible cash donations to Rs 2,000 marks an important shift away from opaqueness.

This argument seems to hold water for Bhasin as well, who views the new system involving electoral bonds as a “substantial improvement” from the previous system.

We are a “work in progress nation,” he says. “All of these systems are also a work in progress”.

Also read: Three men, a great orator, Gandhi—all that led to the birth of Vaikom Satyagraha 99 years ago

Different democracy, same debate

The 1990s were a period of dramatic transformation in Indian economy and politics. India’s markets were opening up to the world. The world was the Indian companies’ corporate oyster. However, the political landscape in the country was chaotic, to say the least. The 1996 Lok Sabha elections led to two years of political instability during which the country would have three prime ministers.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the Labour Party had only one mantra: “reassurance, reassurance, reassurance” — it was trying to reassure the public that this was not the old Labour. During these reassurances came the 1997 manifesto declaring “new Labour because Britain deserves better”. Among other things, its manifesto said that if elected, it would “clean up politics”, including the funding of political parties.

The party saw a landslide victory, and the UK passed the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The law controls donations to registered parties and their members, restricts campaign expenditure, as well as lists down accounting requirements for parties.

This is the kind of window of opportunity that Sethia believes can act as a catalyst for bringing in reform in political party funding in India. The biggest roadblock, he asserts, is that of “foxes guarding the hen house” – that political parties having to place limits or restrictions on their own funding.

Also read: Adani controversy brings back the story of how Manmohan Singh govt rescued Satyam

Uncivil disobedience: Not complying the CIC mandate

In their opposition to transparency in political parties, these foxes have stuck together in the past. In 2013, parties across the country were gearing up for a tough fight in the upcoming general elections, all ready to bring the other down. However, amid this, there was one issue that was holding them together tight. None of them wanted to be covered by the Right to Information Act 2005.

In June that year, the central information commission declared six national political parties–the INC, BJP, CPI(M), CPI, NCP and BSP– to be “public authorities” under the RTI Act. What this meant is that political parties were therefore required to make disclosures and provide information under the law.

The judgment, of course, sent the parties into a frenzy. The Department of Personnel and Training sent a note to the cabinet in July 2013, proposing to amend the RTI Act 2005 to explicitly exclude political parties from the ambit of the right to information.

However, in March 2015, the CIC admitted that it was powerless to enforce its own ruling, calling it a case of “wilful non-compliance” by political parties. The Association of Democratic Reforms and RTI activist Subhash Chandra Agrawal then approached the Supreme Court in 2015, demanding that all the national and regional political parties be brought under the ambit of the RTI Act. This case is pending before the court.

In June that year, the central information commission declared six national political parties–the INC, BJP, CPI(M), CPI, NCP and BSP– to be “public authorities” under the RTI Act. What this meant is that political parties were therefore required to make disclosures and provide information under the law.

Meanwhile, ADR’s founder-trustee Jagdeep S Chhokar confirmed to ThePrint that the CIC’s order has not been challenged in any court, and has therefore become binding.

“Yet we have a situation where political parties have refused to comply with the ruling of the CIC, so we call it uncivil disobedience,” Bhardwaj, who is also a founding member of Satark Nagrik Sangathan, says.

This debate also brings in the question of a voter’s right to know, which has so far been extended to right to knowing a candidate’s criminal antecedents, personal assets, and educational qualifications.

However, Bhardwaj advocates for similar transparency for political parties while pointing out the crucial role they play in India.

“In India, people usually vote for parties, not for individual candidates,” she says, also emphasising on the existence of the whip.

“So parties determine who’s going to vote which way. Individual legislators really have very little say in things,” she adds.

Also read: 100 yrs of Soviet Union: Nehru-Indira era over, but idea of USSR still rules Indian mind

A piece in the puzzle

In a country that tops digital payments rankings globally, donors can still contribute to political parties in cash— capped at Rs 2,000. However, as seen with the Rs 20,000 disclosure limit, any such cap can be exploited by breaking down big donations into smaller packets.

Sethia also points at these loopholes and suggests that they need to be plugged for any real change on ground. He recommends that a simple way to do it would be to apply the Rs 20,000 disclosure limits to “aggregate annual contribution” by every single donor. This would mean that an individual or a company would not be able to contribute more than Rs 20,000 in a financial year.

“This might at least make it more difficult for donors to do that anonymously,” he says.

Vaishnav says that even if electoral bonds are out of the picture, several concerns remain unaddressed, including the lack of the requirement for parties to maintain independently-audited disclosure of their income and expenditure, as well as the Election Commission being powerless.

“So it would solve a piece of the puzzle, but not the entire puzzle,” he says.