PastForward is a deep research offering from ThePrint on issues from India’s modern history that continue to guide the present and determine the future. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Indians are now hungrier and curiouser to know what brought us to key issues of the day. Here is the link to the previous editions of PastForward on Indian history, Green Revolution, 1962 India-China war, J&K accession, caste census and Pokhran nuclear tests.

NASSCOM president Som Mittal was in a meeting on the morning of 7 January 2009, when his secretary burst into the room with a freshly faxed letter. Mittal’s face turned white when he read it.

The letter was from his friend and known associate, Ramalinga Raju, the founder of Satyam Computer Services. Dispatched to multiple people including SEBI chairman CB Bhave, that one piece of paper sent India into a tailspin. Raju had confessed to the now infamous Satyam Scam.

Mittal swung into action. As president of the National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM), he headed the apex body for the Indian technology industry of global repute. To Mittal, the letter signalled a credibility crisis in an industry that was driving the country’s economy.

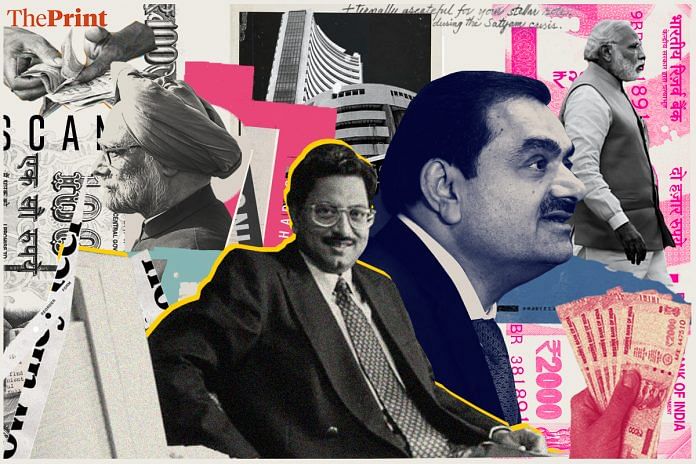

India has seen multiple scams since Satyam — the country’s largest corporate fraud at the time. But few have had such an international impact. The latest follows a report by the US-based Hindenburg Research, which accuses industrial giant Adani Group of carrying out “the largest con in corporate history”.

The Narendra Modi government is keeping the Adani Group at arm’s length, maintaining that the crisis will “play out” in the Indian markets. Questions raised by opposition leaders in Parliament remain unanswered — whether it’s the home ministry’s security clearance to the group to operate ports and airports or Prime Minister Modi’s foreign visits resulting in new business deals for Adani. The finance ministry has dismissed the market rout as a storm in a teacup, saying that Indian regulators and public institutions are strong enough to weather the crisis out.

But that’s not what happened with Satyam: the Manmohan Singh government dove headfirst into the situation.

“If the government wants to move, it moves,” said senior bureaucrat Anurag Goel to Mittal on the day the news of the Satyam scam broke.

And the government moved. And how. Within 100 days, Satyam, or what was left of it, was catapulted into a new, shiny, clean entity — Tech Mahindra.

But today, with another industry giant facing a similar storm, the Modi government has excused itself from the stage.

“I don’t think there’s anything for the government to do either for or against any party in this [Adani] transaction,” finance secretary TV Somanathan said to ThePrint. “This is between a private company and its regulator and the markets and the stock analysts. There are actors who have to sort this out among themselves. I don’t think the government comes in at all.”

Both Satyam and Adani have played notable roles in the country’s development. Both became intertwined with India’s global reputation. Both stand accused of inflating company value. In Satyam’s case, government intervention proved golden.

“Once again, this is India’s hour. We’ve built a brand, we’re sought after, we have a global reputation,” Mittal told ThePrint referring to Adani. “At this time too, we can’t let our credibility be affected.”

Also Read: ‘Hindenburg report on Adani Group saved our livelihoods,’ say truckers in India

Saving Satyam

All hell broke loose when Raju’s infamous letter reached various offices. Pandemonium reigned everywhere from Dalal Street to Lutyens’ Delhi — at first, it was an incredulous shock which quickly turned into full-blown panic. Everyone seemed to have missed the smoke, and now the fire had engulfed the room.

Saving Satyam became nothing less than a patriotic duty.

A month before the confession, on 16 December 2008, Raju called a board meeting where he proposed an outrageous idea — that Satyam acquire two of his family businesses, Maytas Properties and Maytas Infra.

Raju had been reporting profits and cash that did not exist, falsely inflating Satyam’s share prices — he had manipulated approximately Rs 12,000 crore in several forms since the mid-’90s. The acquisition was his last-ditch attempt at a cover-up, he was trying to replace Satyam’s fictitious money with Maytas’ real assets. In retrospect, the idea was brilliant. But the proposal was shelved after investors, analysts, and the international market strongly pushed back against it.

Once Raju confessed to cooking the books, Mittal wasted no time. His first thought was regarding the havoc it would wreak on an industry that ran on trust. It was his job to prevent that from happening. He dropped everything and flew from Delhi to Hyderabad, where Satyam was headquartered. He acted as the government’s liaison until they had a plan of action.

“The money might have been fake, but there were real customers, real employees, and real profits involved. I told the government to hang the man — but don’t put a lock on the door,” said Mittal. The priority was introducing confidence-building measures to save the industry.

Satyam offices were shut when Mittal went the next morning and the press lay in wait outside. He “scaled the walls” of the head office, spoke to the senior employees along with analysts and government officials, and held a dummy press conference to prepare the staff.

“It was like being in an ICU (Intensive Care Unit). The aim is to save the patient and everybody steps in,” Mittal said. “The patient came out alive, thanks to the new board, and was convalescing. Then Anand Mahindra stepped in to save and rehabilitate the patient.”

Also Read: What degree of dominance do India’s biggest businesses enjoy? Decoding the Billionaire Raj

The first 72 hours

The first 72 hours are the most critical to contain a crisis. Satyam was no different.

“Under the law, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs can step in and change the board and in effect, the company would become government-managed,” said Montek Singh Ahluwalia, then-deputy head of the Planning Commission. “I thought that was the wrong thing to do because while the government can change the board in the event of clear self-admitted mismanagement, it would be a disaster if we had just put a bunch of government servants on the board.”

On 8 January, barely 24 hours after Raju’s confession, Anurag Goel, from the office of Prem Chand Gupta, then Minister of Corporate Affairs, made three important calls after consulting with several people including Mittal and Ahluwalia, wrote T. N. Manoharan and V. Pattabhi Ram in the 2022 book The Tech Phoenix.

The first call was to Kiran Karnik, who preceded Mittal as NASSCOM president. The second to Deepak Parekh, a Padma Bhushan award-winning banker. And the third to C. Achuthan, a legal expert and member of the Securities Appellate Tribunal in SEBI. They were the first to be invited to form the new board of Satyam.

Three more were added later— Tarun Das, S. Balakrishna Mainak, and T.N. Manoharan.

The Manmohan Singh government sacked Satyam’s board and appointed a new one to steer the ship within 72 hours of the letter. All the names on the new board had been cleared by the PMO. The number one priority was to keep morale high and restore public confidence.

“Satyam associates felt deserted, not orphaned,” wrote Manoharan, a newly-appointed board member and former president of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India. Government intervention had infused a sense of reassurance inside the Satyam offices.

After the first meeting of the new board on 12 January, Deepak Parekh told the media that many “Satyamites have reached out reaffirming their commitment to the company and their desire to see Satyam reach greater heights”.

The crisis hung over everyone’s heads — but their morale was strong enough to keep their knees from buckling. The board dived head-first into firefighting. PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), the statutory auditors, had declared their audits (held from 20 June 2000 to 30 September 2008) unreliable.

First, legalities were handled. Amarchand & Mangaldas & Suresh A Shroff & Co (AMSS) was appointed to handle the legal crisis in India. Latham & Watkins handled it in the US.

Incidentally, in 2015 AMSS split into two factions and one of them, Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, has represented the Adani Group in key deals. And Cyril Shroff, managing partner of the firm, is the father-in-law of Gautam Adani’s son Karan Adani.

Second, the business side was heard. Over Rs 500 crore was set aside to pay employees’ salaries and company bills. The Income Tax department had frozen Satyam’s bank account due to non-payment of statutory dues. Meanwhile, banks used the money in Satyam’s accounts to settle the amounts that Raju owed them. KPMG and Deloitte were jointly engaged to conduct a forensic audit. A Chennai-based accounting firm, Brahmayya & Co, were appointed to carry out an internal audit.

Manoharan chalked out audit plans with Deloitte and KPMG. But the firms couldn’t provide an estimated completion date — the nature of the fraud was massive and Satyam’s verticals operated in silos. Inflated billing, non-existent cash and bank balance, overstated debtors and discrepancy in operating margin — Satyam had inadvertently turned itself into “Frankenstein’s monster,” according to Manoharan.

Even as the board members were dousing the fire, the opulence of Satyam Computers remained. In the grand dining hall, the new board of directors and executives enjoyed vegetarian and non-vegetarian food accompanied by hot Indian breads, served by caterers in starched white uniforms. But according to Manoharan, lunch was not a break, they were still poring over documents and making calls to save the sinking company.

Also Read: Modi govt open to SC’s ‘expert panel’ idea to avoid Adani repeat, but wants to appoint its members

The rescue operation

Satyam’s global reputation was linked to the information technology (IT) boom in India. The significant international attention — coupled with the noise being made by bodies like Nasdaq and PwC — meant that not just Satyam’s but the reputation of India’s entire IT sector was at stake.

The new board’s objective, according to Mittal, was not to run the place — but keep it afloat until it found a home.

While the board meetings were in session, long-time clients such as Nestle, Walmart, Caterpillar, and Nissan badgered members with phone calls, wrote Manoharan and Ram.

The Manmohan Singh government wanted to resurrect Satyam, but some arms of the government hovered over the company, hounding it to clear their dues. The Income Tax department demanded dues amounting to Rs 54 crore and gave Satyam 10 days to pay it, even though the law allowed a 30-day deadline. The constant interrogation and jurisdiction-based inquiries by regulatory and investigative agencies such as Serious Fraud Investigation Office (SFIO), Economic Offences Wing (EOW), Enforcement Directorate (ED), Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) was also extremely demoralising for the employees. Even the US agency against market manipulation, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), investigated the matter as Satyam was listed on Nasdaq.

By 22 January, two weeks after the letter was sent, the board narrowed the strategies down to two to rescue Satyam, wrote Manoharan and Ram. One was to convert it to a shell company, which would eventually result in it being wound up. But no one wanted to sentence it to a corporate death.

Their second option was to sell the shares to a new investor. It would have to be a lock, stock, and barrel purchase — forensic audits continued, SEC and SEBI requirements met with, and all notional amounts cleaned up. Questions arose. How do you bring the investor? And when?

The unspoken third option — making the government steer the ship — didn’t seem like a good idea. NR Narayana Murthy (Infosys) and Shiv Nadar (HCL) were private players, and unlikely to buy shares or acquire Satyam if it became a government entity.

But the last option didn’t have to be seriously considered, private players had taken the bait and were showing interest in a merger.

Over the course of the following weeks, board members ensured that employees cooperated in the investigations by the ED, SFIO, CBI, and SEBI.

Apart from the internal strategy to rebuild Satyam, there was also an unwritten industry-wide “no poach pact”. This meant that competitors would neither pursue talent from Satyam’s ranks nor would they capitalise on the crisis to tap into Satyam’s client base, according to N Dayasindhu, co-author of Against All Odds: The IT Story of India.

The Congress government, too, offered “unconditional support” — signalling the sectoral significance of a company like Satyam in the late 2000s. Relaxations given to Satyam were favourable, and petitions were quickly approved. Then-corporate affairs minister PC Gupta even told the Railway Board in a letter that “benefits normally available to government companies may also be extended to Satyam”.

“The idea was to let [Satyam] be taken over by a credible bunch of private sector people and obviously throw out the earlier management,” said Ahluwalia to ThePrint. “I think that worked. They did bring in a fairly transparent bidding process, nobody ever complained,” he added.

Mahindra enters the picture

In a bid to establish trust in the sector, NASSCOM told clients that the fraud was one of financial reporting and not directly related to the firm’s numerous projects. Meanwhile, the government-appointed board primarily focused on steadying the ship and finding the right buyer, Dayasindhu told ThePrint.

That buyer would turn out to be Tech Mahindra, a joint venture between the Mahindra Group and British Telecommunications established in 1986. A mid-sized firm at the time, this was the company’s golden chance.

The firm was one of the multiple initial contenders for Satyam’s acquisition alongside Larsen & Toubro, led by AM Naik, and MCorp Global Communication, led by BK Modi, wrote Zafar Anjum in The Resurgence of Satyam, The Global IT Giant.

L&T had increased their stake in Satyam from 4.48 per cent to 12.04 per cent. Directors wondered if this was a sign of confidence.

By the time of auction day, 13 April 2009, American investor Wilbur Ross had emerged as one of the three final bidders along with L&T and Tech Mahindra. The latter quoted the highest share price (Rs 58) of the three — a price unimaginable in the previous quarter.

Government-appointed board chairman Kiran Karnik announced the winning bid. Tech Mahindra would acquire a controlling stake (51 per cent) in Satyam for Rs 2,889 crore and the Mahindra Group entered the IT sector.

“Tech Mahindra emerged a dark horse in the process…That very day, Tech Mahindra’s shares went up by 13 per cent in reaction to the takeover,” Anjum wrote.

A key figure in the buildup to the Tech Mahindra acquisition deal was then-CEO Sanjay Kalra.

“What I recall [about the deal] is pretty sloppy. I’ve moved on and shut out that period of my life. It was consuming all of us and I got out,” Kalra told ThePrint.

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Ramalingam Raju was handcuffed by the Andhra Pradesh Police on the same day as he sent the letter. Families in his village went into mourning. They suspended all celebrations around Sankranti, be it cock fights or card games.

They did not want to understand the scam nor know the truth. To them, Raju was a ‘god’ who could do no wrong.

The spectre of crony capitalism hangs over the multiple corporate scams India has seen — and Raju was no exception. The suave, charismatic man came recommended by no less than Bill Gates, and he caught the eye of the political establishment in undivided Andhra Pradesh.

“From the very beginning, Satyam was raised to the sky,” said veteran journalist Kingshuk Nag, then bureau chief and resident editor of the Times of India in Hyderabad. Nag also wrote The Double Life of Ramalinga Raju: The Story of India’s Biggest Corporate Fraud, based on his coverage of the scandal. “Raju was introduced as a star, and then he just continued to rise in India,” Nag said.

He cautioned that Satyam’s turnaround has been memorialised as a success story without prompting introspection into why the situation arose in the first place.

“The company was saved, and a lot of people were happy. Now the question was: what did the company have? It had only fictitious income,” said Nag. “If your aim is to protect the company and allow it to go on, then this rescue operation is a success. But the guilty weren’t properly brought to justice.”

But Raju wasn’t a villain in everyone’s eyes.

“He was Mr Hyde by circumstance and Dr Jekyll by nature,” said Manoharan. Raju’s Mr Hyde persona was a product of the IT boom in India. Honesty and ethics didn’t yield much profit for Raju during the late ’90s and early 2000s. Infosys had ballooned into India’s IT giant, Y2K bug was fixed, HCL was at its prime. According to Manoharan, Raju perhaps couldn’t resist biting the bait — overstating billing so that the company entered the big leagues.

He fudged the numbers every subsequent quarter. The gaps kept getting bigger, and bigger. “It was like riding a tiger, not knowing how to get off without being eaten,” Raju said in his confession letter.

But many who knew Raju saw him as Dr Jekyll. He was revered in his native village in West Godavari. From hospital services and provision of medicines to water purification — Raju had brought unparalleled changes. There was so much goodwill around him that even after the scam came to light, a Raju-acolyte told Manoharan, “The boss had put himself on the chopping block to let Satyam stay afloat.”

Raju was fined Rs 5.5 crore and convicted of fraud on 9 April 2015 and sentenced to seven years in prison. On 11 May 2015, his term was suspended and he walked out of the prison gates.

“Mr Raju was a friend of ours — he was the simplest soul. I would trust my family with him,” said Mittal, reminiscing about the man who caused so much chaos in his life and the lives of countless others.

“All the gurus — all of us combined — didn’t detect the fraud,” added Mittal. He paused, “It just goes to show you our ability to judge people.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)