Off the coast of Ireland in the late evening of 23 June 1985, a rescuer from the British Royal Air Force retrieved a doll from the site of an airplane wreck. Frustrated at first since he thought many people needed to be rescued, he would soon realise that every passenger was lifeless. Among them was the sari-clad body of an older woman, split in two, and joined only by her intestines. He watched her float away, the image haunting him for the rest of his life.

On that fateful day, Air India Flight 182 disintegrated mid-air on its way from Canada to India, causing the death of all 329 members on board. It was an unthinkable act of mass murder, orchestrated by Sikh extremists at the height of the Khalistan movement — and the deadliest act of aviation terrorism before 9/11.

It came after months of Indo-Canadians saying the same thing: “Air India ki flight mat lo (Don’t take an Air India flight).”

The Khalistani sentiment has always maintained a tenacious grip in a section of Sikhs in Canada, as the celebration in Brampton of former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination early this month proves.

This history of communal hatred still hurts the broader Sikh community in Canada — many in the country are still haunted by the horrors of the Air India flight bombing and its aftermath.

“Any glorification of hate that promotes violence makes me sad. It is abhorrent,” says Susheel Gupta, who lost his mother to the bombing when he was 12 and is the chief of the Ottawa-based Air India Victims’ Families Association. “I still meet people today who were somehow connected with the Air India bombing — my kindergarten daughter’s teacher was a schoolmate of a victim. It is surprising how widely the bombing affected Canadians.”

Not just a ‘cascading series of errors’

There were rumours for months among the Indian diaspora in Canada that something big was going to happen. Plenty of signs were visible too — but no one was paying close attention.

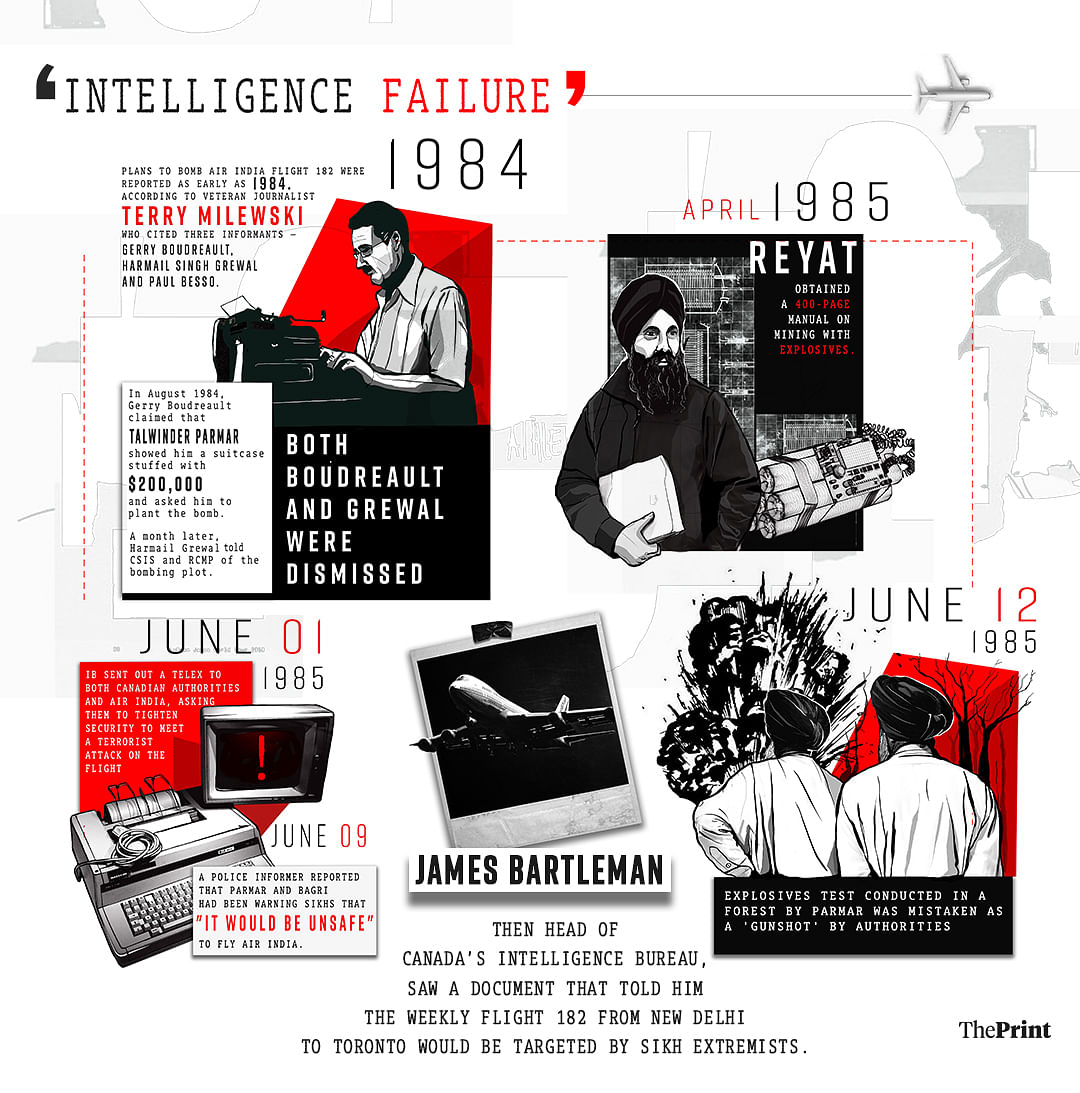

The whispers eventually grew loud enough for the Indian Intelligence Bureau to hear. They sent out a telex to both Canadian authorities and the Air India administration on 1 June 1985, asking them to take security measures against a possible airplane attack by Sikh extremists.

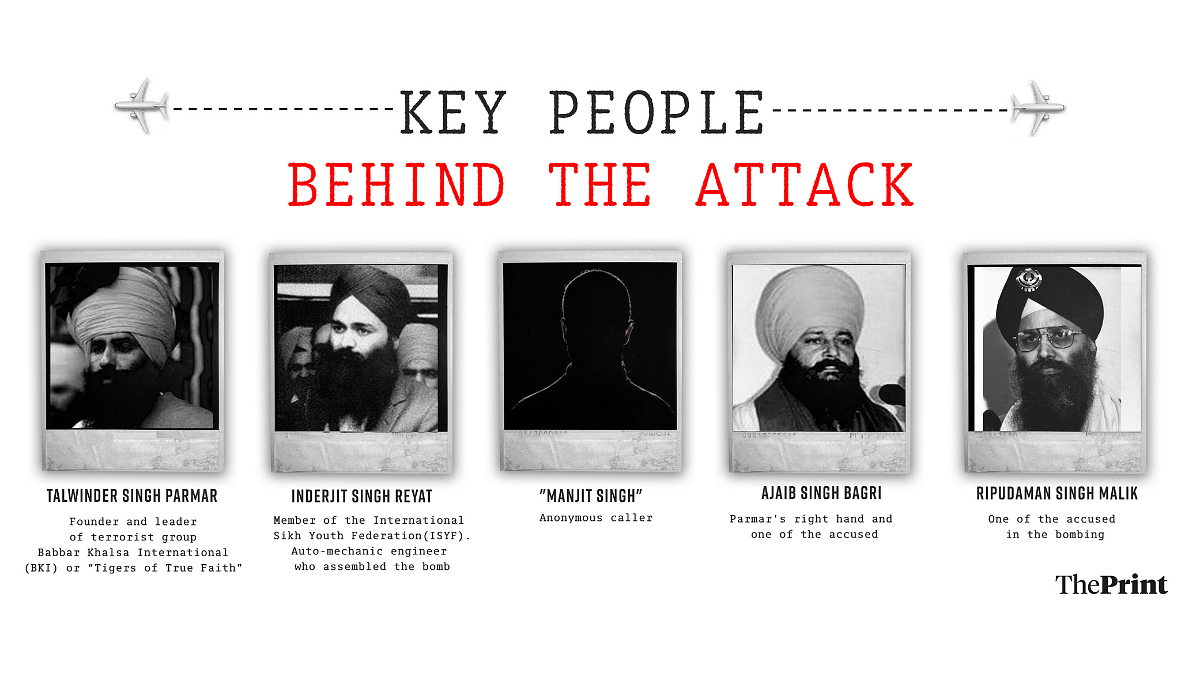

But that wasn’t all. Days before the bombing, Canadian intelligence operatives who were tracking Talwinder Singh Parmar, founder and leader of terrorist group Babbar Khalsa International (BKI) or “Tigers of True Faith”, heard an explosives test that he conducted in a forest. They ignored it, mistaking it to be a “gunshot”.

Surveillance was called off the very next day.

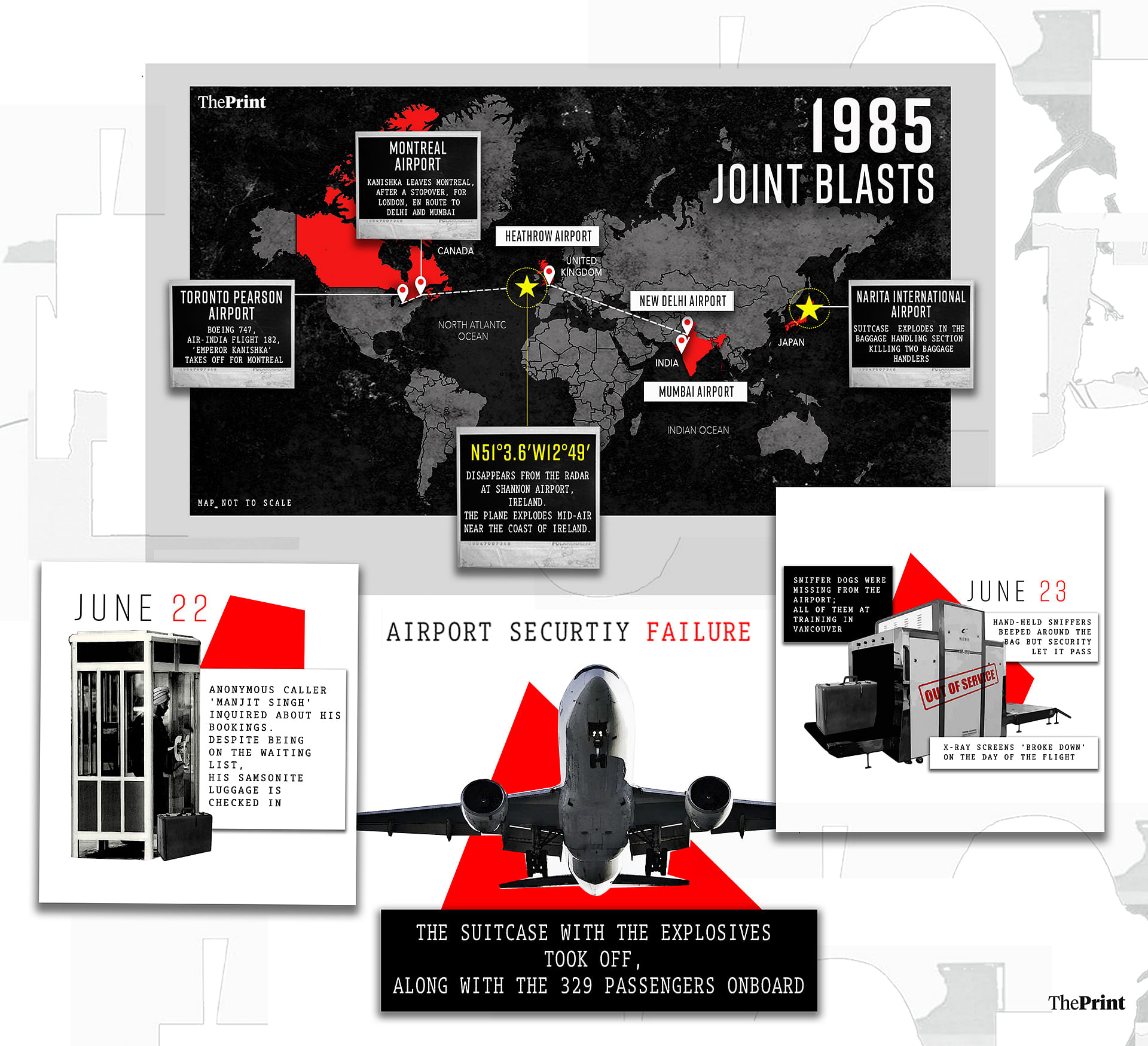

What’s more, Canadian security was lax despite the evidence of threat. Sniffer dogs were missing from across Canadian airports because all of them were at a training season in Vancouver. X-ray screens at Toronto’s Pearson Airport ‘broke down’ on the day of the flight.

Meanwhile, a man called “Manjit Singh” called the airlines on 22 June, asked if his ticket was confirmed, and was told that he was on the waiting list. He then asked for his Samsonite luggage to be checked in regardless — and therein was planted the bomb on Flight 182, a Boeing 747 plane named ‘Emperor Kanishka’.

The hand-held sniffers, which were supposed to scream near explosives, did beep around the bag — but security personnel weren’t trained to detect the signal, so they let it pass.

Then, at Montreal’s Mirabel airport — the first stop after take-off from Pearson — several suspicious bags were identified. However, cost considerations motivated Air India officials to allow Flight 182 to depart—the plane was already late, and the airlines would have to pay a fee otherwise.

The suitcase with explosives took off, along with the 329 passengers onboard.

Perhaps the most damning of all: James Bartleman, then head of Canada’s intelligence bureau, saw a highly classified Communications Security Establishment (CSE) document that told him the weekly Flight 182 would be targeted by Sikh extremists. When he brought it to the attention of an RCMP official, he was met with a hostile reception and told that the matter was being probed by the officials.

When he further testified to this in court, Canadian authorities did their best to discredit him.

All these deadly lapses are chronicled in unsparing detail in the 2010 report of the John Major Commission, appointed in 2006 by the Canadian government to look into the bombing and the role of both intelligence and police.

Headed by retired Canadian Supreme Court Justice John Major, the commission’s findings chronicle a shocking level of laxity, coming down hard on the Canadian authorities. The report points out the “cascading series of errors” that led to the largest “mass murder” in Canadian history — and one of the most significant terror attacks on an airplane.

Over the years, critics have referred to the Canadian authorities’ attitudes as racially tinged and negligent. This indifference, they say, also currently informs the Canadian government’s response to Khalistani supporters.

Although multiple people were arrested and tried for the 1985 crime, including Parmar, only one was convicted to 15 years in prison — Inderjit Singh Reyat. Some of the others associated with the Kanishka bombing were allowed to re-enter society and were seen to be close to Canadian officials.

“It wasn’t a cascading series of errors. It wasn’t an intelligence failure — unless you describe criminal negligence and collusion as failure,” says Ajai Sahni, founding member and executive director of the Institute for Conflict Management.

“It was malice aforethought on the part of the Canadian leadership.”

Anatomy of a terror attack

Plans to bomb Air India flight 182 were reported as early as 1984, according to veteran journalist Terry Milewski, who cited three informants — Gerry Boudreault, Harmail Singh Grewal, and Paul Besso.

Boudeault was a French-Canadian career criminal from Calgary who “knew how to hustle to make a buck, how to make a deal to cut time spent in prison, when to keep his mouth shut, and when to rat to the police”, while Grewal worked in a liquor store in Vancouver and faced robbery charges. Besso used to be an explosives expert with the Canadian Navy and later became a paid informant for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), assisting on drug busts and infiltrating a group of Sikhs in Vancouver, according to Brian McAndrew and Zuhair Kashmeri’s Soft Target.

Boudreault and Grewal told the RCMP of their direct involvement with the Babbar Khalsa militants in August and September 1984, while Besso claimed to have recorded a discussion planning out the attack in June 1985.

Boudreault revealed that he was offered $200,000 in cash to smuggle a bomb onto Flight 182, and Grewal independently told RCMP about the same meeting between Vancouver-based Sikhs and Boudreault, Milewski wrote in Blood For Blood.

Moreover, McAndrew and Kashmeri write that Besso had met with the purported US head of the International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF), informing the RCMP not only of the plot to bomb an Air India flight but also of the ISYF’s interest in procuring “automatic weapons and 75 per cent pure dolomite plastic explosives to blow up bridges in India”.

But Boudreault, Grewal, and Besso were all deemed “not reliable” by the Canadian police and intelligence services, according to Milewski.

The actual attack involved two bombs assembled by Vancouver Island-based auto mechanic Inderjit Singh Reyat.

He had taken his orders from Parmar, who was originally from Punjab’s Kapurthala district and had emigrated to Canada in 1970 when he was about 26 years old. Parmar had become a Canadian citizen in 1976, with his adopted nation and Pakistan serving as “bases for his rise to prominence”, Milewski wrote.

Reyat would claim years later during a court trial that he was unaware of the purpose of these bombs, but local Canadian witnesses had contradicted him, citing his stated desires for “revenge” for Operation Blue Star and inquiries about dynamite ahead of the bombing.

For about two months prior to the attack, dubbed as Canada’s 9/11, Reyat assembled and tested bombs, while Parmar reportedly coordinated with fellow Babbar Khalsa militants, using payphones and communicating in code.

“Manjit Singh” managed to deceive a CP Air agent at Vancouver airport to check in his bomb bag onto Flight 182. This despite not having a confirmed flight ticket beyond the Vancouver to Toronto leg of the India-bound flight, which was scheduled to stop over at London Heathrow and Delhi’s Palam Airport before ending at Mumbai.

That fateful, dark brown Samsonite bag evaded the beefed-up Canadian airport security requested by Air India for Toronto and Montreal. The bomb aboard the flight exploded over the Atlantic Ocean, killing all aboard.

That same day, another Babbar Khalsa militant successfully checked in a bag containing a bomb onto a CP Air flight bound from Vancouver to Japan’s Narita International Airport from Vancouver, in the absence of X-ray security checking.

This bomb-bag was intended for Air India Flight 301 scheduled from Narita to Bangkok. The plan was for the bomb to explode at the same time as the one on Flight 182, but the blast took place an hour earlier at Narita airport as the militants had failed to account for Japan not observing daylight savings time. Two Japanese baggage handlers were killed in the explosion.

Also read: 100 yrs of Soviet Union: Nehru-Indira era over, but idea of USSR still rules…

‘You’re not worth it’

Out of 329 Kanishka fatalities, only 131 bodies were found. The wreckage was strewn across the Atlantic Ocean, the remains off the coast of Ireland.

Then began another story of official indifference.

According to testimony from victims’ families, when they landed in London en route to Ireland to identify the bodies of their loved ones, there was no Canadian presence at Heathrow airport to help them.

In contrast, Air India had arranged for free passage from Canada to Ireland — and the Indian ambassador to the United Kingdom was described as “very helpful and supportive”.

“The community as a whole has been broad-brushed with ‘you’re not worth it’, ‘move on’, ‘this happens’, ‘there are wars’, ‘just move on’,” said the daughter of 60-year-old bombing victim Nana Kachroo, who described herself as simply Canadian, having lived in the country for seven years.

One of her sons would renounce his Canadian citizenship. Kachroo and the other victims were not “citizens of convenience”, her daughter testified in court.

Ironically, one passenger’s bag was taken off the plane at Mirabel Airport after it triggered a false security alert. His grieving widow later testified that she wished he was taken off the plane as well. His body was never found, and only his confiscated bag was returned to his family.

Trial, encounter, acquittals

The Air India 182 trial was the longest and most expensive one in Canada’s history, dragging on for over two decades and costing nearly $130 million.

Yet, for all of this, it was largely an exercise in futility — the events of 1985 and subsequent years followed a trajectory of disaster to disorder to disregard to defeat.

From a promising start with the RCMP and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) launching investigations in 1985 to Reyat being charged with manslaughter and possession of bombs in 1991, the trial reached a plateau after Parmar was killed in a police encounter in India in 1992.

Parmar was the central figure in the 1981 murder of two Punjab police officers amidst his terrorist activities in India, but he went back to Canada and even travelled to West Germany. Both countries refused to extradite Parmar to India, with West Germany jailing him for a year before letting him go.

“Western governments were not keen to take sides in India’s internal battles,” Milewski wrote in Blood for Blood.

In the years following the Flight 182 bombing, Parmar moved to Pakistan in 1988 and continued his activities underground across the border in Punjab until his death.

However, a shadow looms over the days leading up to the 1992 encounter. Retired Punjab Police DSP Harmail Singh Chandi alleged in 2007 that he had interrogated Parmar for five days before the latter was killed in custody on the orders of senior officers. Chandi claimed these senior officers also wanted Parmar’s confession record, detailing the extent of his involvement in the bombing, to be “destroyed”.

The trial, meanwhile, was going nowhere and the RCMP even offered a $1 million reward for information leading to conviction in 1995. It was around this time that Tara Singh Hayer, publisher of the Indo Canadian Times, a staunch critic of Sikh extremism, and a crucial witness, gave the RCMP a much-needed smoking gun.

He submitted an affidavit to the RCMP, mentioning a conversation between Ajaib Singh Bagri—Parmar’s right-hand and one of the accused in the bombing—that he overheard and which practically laid out the entire plan.

According to this affidavit, Bagri said that the purpose of the attack was to “make the Indian government come on their knees” and give them Khalistan.

“If everything had gone to plan, the plane would have blown up at Heathrow airport with no passengers. But because the flight was delayed, it blew up over the ocean,” Bagri reportedly told his friend.

But in 1998, Hayer was shot dead. His murderers were never found.

Two years later, informant Surjan Singh Gill, who once called himself the “Consular General of Khalistan” and was a close friend of Parmar, destroyed 150 hours of taped conversations with Sikh extremists instead of turning them over to the RCMP.

Allegedly working as a CSIS mole, he had infiltrated Sikh circles and was reportedly instructed by his bosses in the intelligence agency to pull out three days before the bombing when officials recognised how serious the threat was — allegedly to avoid Canadian intelligence seeming complicit in the attack.

“Just as you’re beginning to see a pattern, evidence is wiped out from all the records. This (the Air India bombing) wasn’t a random Boondocks murder, it was nothing except a collusion based on a racist attitude,” maintains Sahni, in a reference to the Canadian authorities’ insouciance towards the Khalistani terrorists prior to the bombing.

In 2003, Reyat pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to five years in prison.

The trial of Bagri and Ripudaman Singh Malik, BKI financier, began soon after. A multimillion-dollar, high-security courtroom called Courtroom 20 was especially built for the purpose.

In an unexpected turn of events, the Crown’s key witness turned up—a woman who claimed that Malik fell in love with her during the early ‘90s. She claimed he had confessed to her about the bombing of Air India 182.

Another key witness, who had been captured meeting with Bagri on CSIS cameras, said she couldn’t recall the visit at all.

“I can’t remember, I can’t remember, I can’t remember,” she repeated 20 times within one hour of testimony.

With evidence wiped out and witnesses silenced or dead, both Malik and Bagri were acquitted of all charges in 2005. Malik walked out Vancouver’s B.C. Supreme Court doors with a smile on his face.

Also read: Take care, Rajiv Gandhi told Prabhakaran. Even gave bulletproof vest before Sri Lanka Accord

Foreigners in India, foreigners in Canada

Most of the Kanishka victims were of Indian origin, but back in India, their deaths seemed like a distant tragedy, something to be dealt with in Canada 11,000 km away.

Except for a tokenistic call between then-Canadian PM Brian Mulroney and Rajiv Gandhi right after the bombing — the former expressing his condolences, the latter half-chiding the Canadian government for not having the bags checked, and both agreeing that there was a “sinister connection” — there was no uproar in the Indian political corridors.

Perhaps, there were already too many larger domestic fires to douse in the India of the violent 1980s. When fear of Sikh extremism sat next door in Punjab, what the Canadians were up to mattered less.

“[The year] 1985 was a period of chaos and violence in Punjab. It followed Operation Blue Star and the assassination of Indira Gandhi [in 1984]. There was a lot going on here as well, and news travelled really slowly,” recalls journalist Rahul Bedi, a reporter for The Indian Express in Punjab at the time.

Sahni acknowledges the tumult of the era too. “I’m not sure [if the] Indian establishment was that concerned…Punjab was on fire. The only person who kept on cribbing was KPS Gill, he was the only one who was talking about it,” he says.

Meanwhile, apathy prevailed in Canada too, albeit for different reasons. Even though 278 of the 329 victims were Canadian citizens who had little to do with India, the attitude seemed to be that they were just foreign casualties of a foreign conflict.

“All India lost is a plane,” said the bereaved father of a victim in an interview with The Globe and Mail, referring to the indifference that reduced his Canadian daughter into a dead foreigner overnight on 23 June.

Ultimately, the bombing became a hot potato issue — for Indians, it was a “foreign tragedy” and for Canadians, it was something “the brown guys were up to”.

Over 20 years later, the Stephen Harper-led Canadian government established the John Major Commission of Inquiry. But not much seemed to have changed about how the attack was perceived in Canada.

At one point, Anil Kapoor, one of the key lawyers in the commission, grew frustrated with the bombing being described as a tragedy. “Getting cancer is a tragedy. This was a terrorist attack,” he snapped.

Writing in The Globe and Mail in 2010, journalist Patrick Brethour underscored how for most Canadians events such as Indira Gandhi’s assassination were just foreign stories— “at the back of the newspaper or the end of a broadcast…an Indian misfortune, not a danger signal”.

There Sikh diaspora lived in Canadian communities, but they were still seen as distant others.

Even to the CSIS, the bastion of Canadian intelligence, Sikh Canadians seemed so foreign that officers “couldn’t distinguish one traditionally attired Sikh from another”, according to the Major report.

Then, despite the racial divides, there was the matter of political correctness— and expediency.

A political landmine

Over the next few decades, nobody in Canada’s political firmament directly addressed the issue of Khalistani militancy. Not even Ujjal Dosanjh, a former Canadian MP who was beaten up in early 1985 for speaking out against attacks on Sikh moderates.

This hesitation stemmed from fear of labelling the entire Sikh community as a “threat” and also the consideration of losing votes, noted Ron Atkey, chair of CSIS watchdog, the Security Intelligence Review Committee, in 2010.

Similarly, addressing the apathy of authorities to the bombing victims ran the risk of branding Canadians as “racist”, which could also cause backlash.

The outcome was that Sikh extremism was allowed to proliferate unchecked in Canada, even as systemic bias was left unaddressed. According to the Major report, the RCMP viewed witnesses as criminals and treated them with scepticism, expecting them to “put up or shut up.”

Amidst this, it was Indo-Canadians and moderate Sikhs who had nowhere to go and nobody to turn to.

While posters of Parmar and militant leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale were plastered at gurdwaras and both figures hailed as martyrs, key witnesses and moderate Sikhs lived under a fog of fear until well into the late ’90s.

Following the bombing, a former friend of Ajaib Singh Bagri had testified before the CSIS that he had allegedly threatened her, saying she “knew what would happen” if she told anyone about his activities.

Another woman claimed she was warned that three men, including the accused Malik, would try to “shut her up permanently” if she testified.

Vancouver journalist Kim Bolan— who would go on to write the 2006 book Loss of Faith: How the Air-India Bombers Got Away With Murder— reportedly received a “hit list” and was told that a person carrying an AK-47 would do the needful.

“I think everybody was afraid and if you said anything that did not support the cause of the people who were trying to support terrorism and violence…you will be called names and…you will be called outside,” said publisher and witness Tara Singh Hayer’s son before the Major Commission in 1986. Hayer was left paralysed after an attack in 1988 and was assassinated a decade later.

Much as the red flags leading up to the bombing had been dismissed, the plight of witnesses and other Indo-Canadians were similarly disregarded.

Even before this, the reverberations in Canada of Operation Bluestar had gone under the radar.

Politician Ujjal Dosanjh touched upon this while testifying before the inquiry commission, noting that Canadian authorities were “unable to deal with a wave of hatred, violence, threats, hit lists, silencing of broadcasters, journalists, activists”.

The former MP and his family slept on his ground floor laid out with mattresses or carpets for several years, fearing extremists would firebomb the house and they would all go up in smoke if they slept on the top floor.

“One watched one’s back all the time,” Dosanjh testified before the commission.

“It’s very difficult to understand the psychology behind this — you had at least three organisations rushing to claim that they were behind this attack,” said DP Sinha, formerly at IB. “If you ask me, it was to gain publicity for the cause. But publicity like this…” he trailed off.

Even in recent years, the Air India bombing has occasionally come up as a contentious issue for Canadian Sikh politicians, including Jagmeet Singh, the leader of the New Democratic Party and prime ministerial candidate in 2019.

When Jagmeet took over the party leadership in October 2017, he reportedly refused to denounce the display of posters of “martyr” Parmar at a gurdwara in Surrey near Vancouver.

Jagmeet had termed Milewski’s question about the incident as “offensive”. It wasn’t until March 2018 that Jagmeet denounced the glorification of Parmar and accepted the Air India Inquiry’s conclusion that Parmar was the mastermind behind the bombing.

Also Read: Mystery of 1966 Air India crash, that killed nuclear pioneer Bhabha, is unravelling bit by bit

Ripple effect to this date

Thirty-eight years after the bombing, Susheel Gupta is holding a memorial service for the victims. It will be attended by families, friends, and influential personalities.

Gupta, who was 12 when his mother boarded the fateful Air India 182 flight, remembers the tragic aftermath of the bombing.

The memory, clouded by trauma, is hazy.

“Whether it was a Canadian or Indian bombing didn’t matter to us. It was devastating, and there was so much pain,” says Gupta.

“In Ireland, to where I flew with my father, it was organised but disorganised — that was certainly troubling.”

While then-Indian ambassador Kiran Doshi and his wife reached out to the families off the Irish coast, there was little help from the Canadian authorities, he recalls.

But was this due to Canadian apathy or the secrecy required by intelligence agencies? “Canadian law enforcement didn’t reach out to many families. We were only told that the investigation was on. They (the RCMP) had run into many challenges too,” Gupta says.

The bombing of Air India 182 sublimated off the radar in 1985, but it continues to haunt families, friends, and the collective Indo-Canadian memory to this date.

“There was so much fear. It impacted so many in the community beyond what you can imagine. I still run into people who remember it. There was a ripple effect throughout the South Asian community,” says Gupta.

And to that end, the Air India memorial in Toronto, Vancouver, and Ottawa is organised “not for any political purpose but to remember the despicable act of terrorism”.

Keeping the memory alive is something Gupta says he and other Indo-Canadians owe to the victims — because history, ultimately, can be easily forgotten.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)