Fifty years ago, Indira Gandhi defiantly faced Parliament and told them that India would not succumb to famine. “We have no intention of failing. We’re going to succeed,” she said. “We shall overcome.”

It was February 1973, and Gandhi was staring at a crisis. Despite the success of the Green Revolution, a widespread drought had affected foodgrain production, and the 1971 India-Pakistan war had pushed the country into further scarcity.

Her solution was for the government to take over the distribution of wheat and other foodgrains, and eliminate the middlemen — private traders.

The move would prove to be a catastrophic failure and be revoked within the year.

Gandhi’s attempt to nationalise foodgrains has gone down in history as one of those turbulent Tughlaq-turnarounds that governments have quietly shoved under the rug.

There have been scores of other such overnight U-turns, like pausing TCS (tax collected at source) for international credit card transactions, the retraction of the retrospective tax in 2012, and the May 2023 decision to recall the Rs 2,000 note.

Wheat nationalisation, however, is usually glossed over as a blip in the turmoil of the 1970s — a decade when India saw a war, political instability, drought, and the Emergency.

But it’s an important glimpse into how the Indian government saw its role at the time. Gandhi described the decision as “major structural reform” to cut out “vested interests” like private wholesale traders who were hoarding foodgrains to create a “psychology of scarcity” while the rest of the country starved.

Under the move, private wholesale trading was banned and procurement prices were made uniform across the country. All wheat transactions, including for government stocks, were handed over to the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and other public sector agencies.

Private retailers were only allowed to operate subject to certain conditions, like stock limits.

The decision ended up creating even more scarcity. And history has written it off as just another move by Gandhi to nationalise a system that didn’t need it.

The decision to recall the policy was a “public admission of major failure in a nation where food production, hunger and political stability are crucially intertwined”, a March 1974 report in The New York Times said.

“[The decision] would have been in response to high inflation post the 1972 drought and 1970s oil shock,” said senior journalist Harish Damodaran, calling it an experiment. “Indira Gandhi had already nationalised banks and coal mines. Probably someone would have said, ‘Why not extend it to grains as well!’”

Also Read: Nehru’s Hindu Code Bill vs Modi’s UCC— same script, same drama, different Indias

Setting the stage

Gandhi saw the policy as a chance to eliminate the entity she saw as the reason for food insecurity: the private trader.

Before 1973, wholesalers or private traders ruled the roost. They would negotiate directly with farmers to buy grains and then sell them to both the government and private shops.

When government shops began running low on grains, the assumption was that private traders were hoarding grains and deliberately raising prices. By taking over the trade and cutting out the middleman, the government thought the problem would be solved.

That didn’t happen.

Government shops found it difficult to adequately distribute grains, which spelled chaos when coupled with low production. The government intended to keep the price of wheat low and stable, which angered farmers who preferred negotiating higher prices with private traders.

As a result, the cost of wheat skyrocketed, shortages were rife, and the weak distribution system broke down.

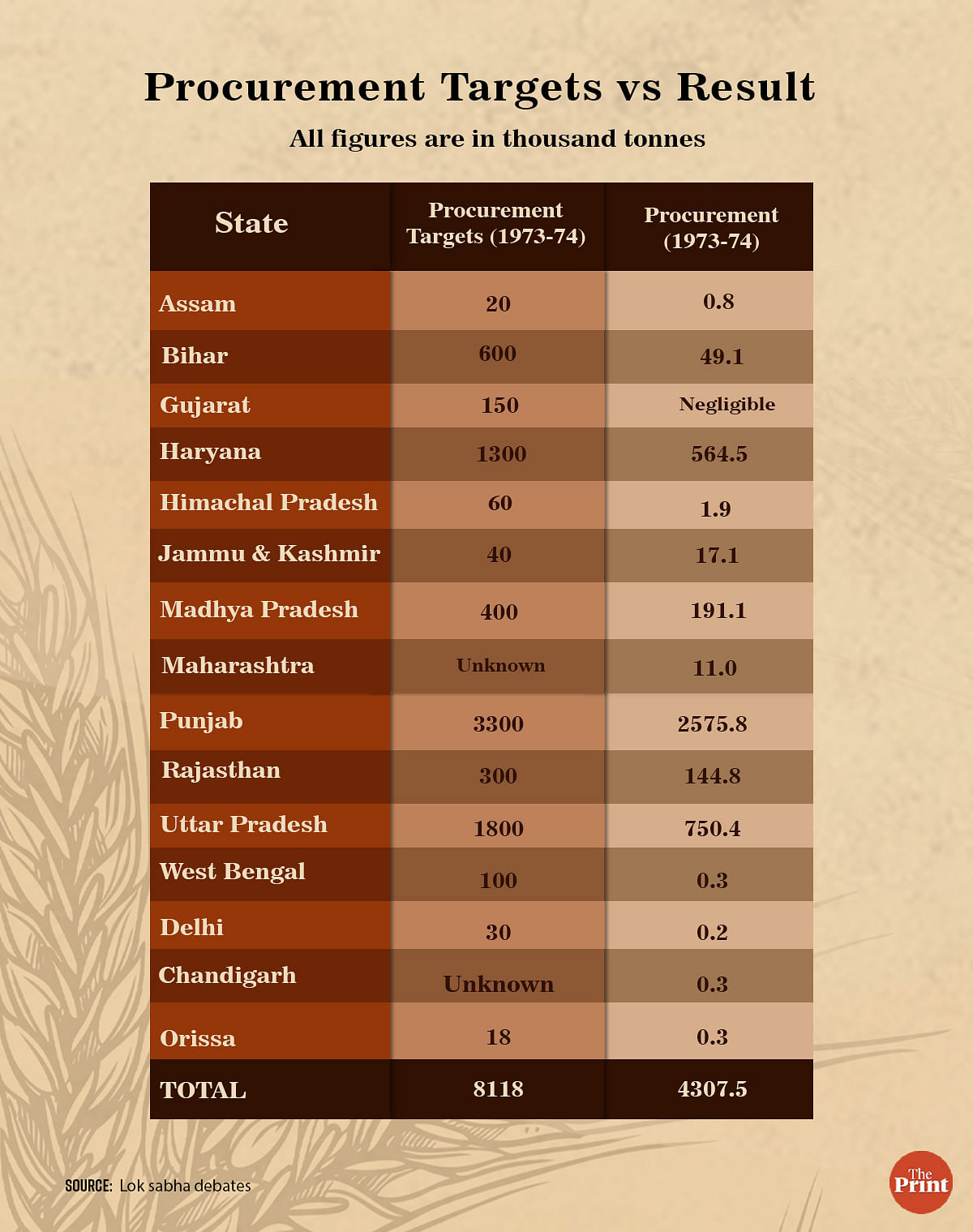

By early 1974, prices had risen by 36 per cent due to the takeover of wheat distribution. The government had expected to produce 14.7 million tonnes of foodgrains that year, but only a little over half of that was produced — 8.5 million tonnes.

Chief ministers in numerous states were concerned about possible violence due to the shortage of food.

The policy was presented as a “pro-farmer, pro-consumer, anti-trader action,” according to Mekhala Krishnamurthy, associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Ashoka University.

But it failed for a litany of reasons. The procurement price of wheat had increased because less wheat was produced in 1973 than in 1972. The international price of foodgrains had risen as well. And to make matters worse, a new rust disease was affecting a high-yielding, double-dwarf wheat called Kalyan Sona.

Added to the government’s already dwindling stock of foodgrains, the year was beginning to spell disaster. Plus, the Indira Gandhi government banked on the idea that increased prices would lead to wholesale traders selling to government agencies, which didn’t happen as planned because of major resistance among wholesalers and traders toward this policy.

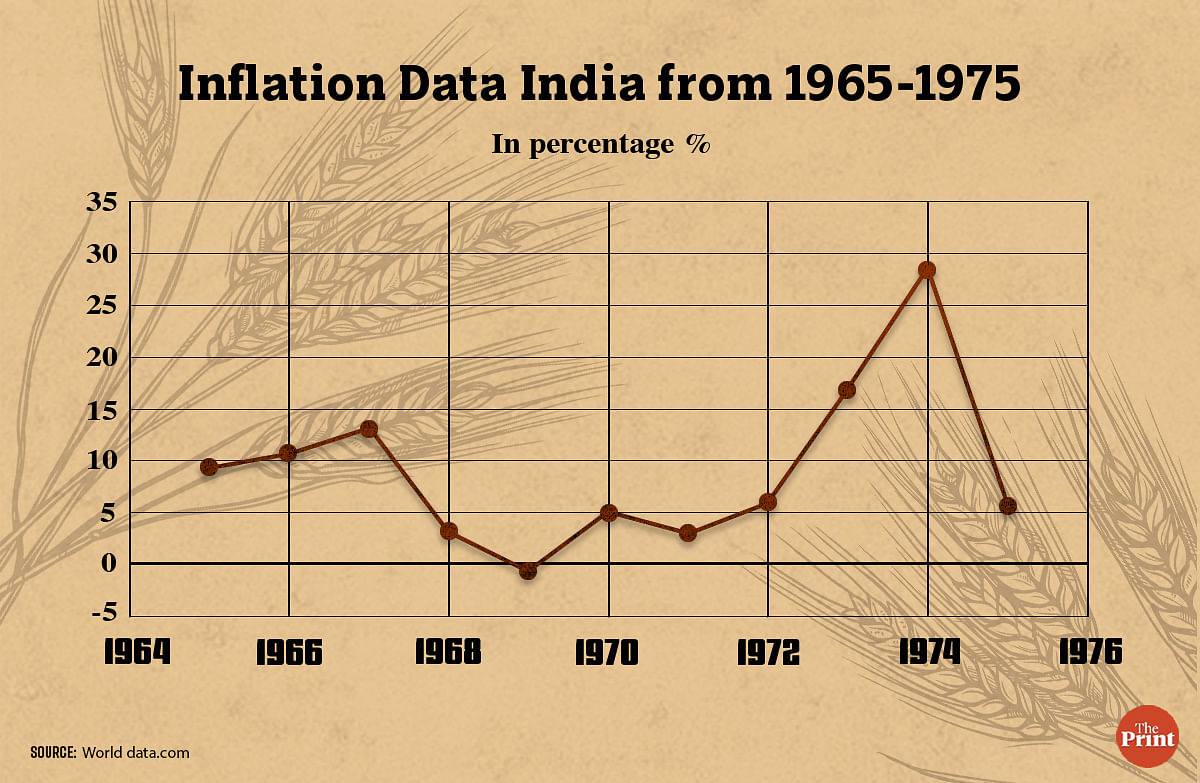

Farmers and wholesalers were angry while the government was floundering, trying to control the panic. The impact was that the first half of 1974 saw the sharpest increase in prices since the war.

Prices of imports were raised, and inflation was exacerbated by the 1973 oil embargo that raised the price of crude oil.

Agricultural and foodgrain production declined even further in 1974 when compared to 1973 — by 3.1 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively.

“Most Indians lived in a period of chronic food insecurity,” said Krishnamurthy. “The distribution system at the time did not cover the vast majority of Indians. We simply didn’t have the kind of distribution system then that we have now.”

The distribution system in India at the time was a power tussle.

“Historically, the political economy of food distribution in India has largely been governed by multiple interests,” economist R. Ramakumar, professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, added.

Private traders — dictated by wealthy, dominant caste groups — largely controlled the system before the FCI introduced procurement support prices in 1965. Most private traders were not pleased with the FCI’s move, which explains their even stronger reaction to the attempted nationalisation in 1973.

Traders tried to sabotage the policy, according to Ramakumar, by hoarding grains or trying to sell directly on the black market instead of the government. And what ensued in 1974 showed just how easily the system could fall apart.

“That is the reason why, on a year-on-year basis, prices rose by 30-50 per cent,” said Ramakumar. “The government was unable to procure the quantity of food it had hoped for from farmers. The amount of foodgrains available through PDS or other channels shrank in the face of hoarding and the black market. The government was not prepared adequately for the task, nor did it have the capacity to carry it out. It was clear that the policy would fail.”

Architect of the policy

In the 1970s, the policy was seen as the brainchild of Leftists in Gandhi’s government.

The real architect, however, was an unlikely figure: DP Dhar, a career diplomat who was appointed Minister of Planning and deputy head of the erstwhile Planning Commission, and steered India’s fifth Five Year Plan.

Dhar had helped orchestrate the Simla Agreement of 1972 and was a trusted adviser to Gandhi during the 1971 war.

He had also served as ambassador of India to the Soviet Union — a close ally of the Indian government — and had negotiated the 1971 Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation. It was a role that Gandhi would only entrust to a close aide.

But Dhar was not an economist by training, and many questioned his appointment as Minister of Planning.

Dhar himself was aware of the criticism.

“Some may question my credentials for this task. They may do so but I have no regrets or apologies to offer them,” he wrote in his book Planning and Social Change. “I may not be a professional sociologist or economist or political theorist. But I am an Indian and a politician and hence have a right to talk about matters that concern me even if this means my poaching in the groves of Academe.”

Planning and social change are too important to be studied by professional social scientists, he added. “In fact even the academic disciplines of economics and sociology are too important to be left to them. To paraphrase — social scientists are not special sorts of persons; every person is a special sort of social scientist.”

Dhar hired top economists like Vijay Kelkar and Arun Shourie as consultants at the Planning Commission, but other members of the planning body were sceptical of his plan to nationalise grains, arguing that buffer stocks were already low because of the drought. One colleague, BS Minhas, even resigned.

But today, many defend Dhar’s logic.

Economist Pulin B Nayak, in his 2015 paper Planning and Social Transformation: Remembering DP Dhar as a Social Planner argued that the nationalisation of wheat trade “was too big an issue that D.P. dared to take on, and the vested interests in this sphere were, and still continue to be, after more than four decades, far too entrenched…

“This particular move of D.P.’s was doomed to failure. But if one considers the simple fact that when, recently, the price of onions had shot up to Rs 80 per kilo in the retail market, it was also known that the growers would be getting no more than Rs 16 to Rs 20 a kilo, it becomes obvious that there is a huge spread that accounts for the surplus going to middlemen and wholesalers, which is a necessary characteristic of the market mechanism. It is this surplus generation that D.P. was interested in curbing”.

Dhar’s stint as Minister of Planning was short-lived. He resigned by the end of 1974 after watching his plan wreak havoc.

Ultimately, even Indira Gandhi thought he was better suited to diplomacy. He resumed his role as ambassador to the Soviet Union and continued until his death in 1975.

Also Read: ‘Air India ki flight mat lo’ — how Canadian neglect led up to Kanishka bombing 38 yrs ago

Nationalisation fever

From banks to general insurance to coal mining, nationalisation became a fashionable trope for the Indira Gandhi government.

“Nationalisation was a buzzword those days,” said Damodaran. “There was a lot of sentiment against big business and traders. It was also reflected in films like Namak Haram, Roti Kapda aur Makan and Upkar. Even in Kala Pathar, private coal owners were projected as villains,” he added.

Besides, the turbulent 1970s were marked by a fourfold increase in India’s petroleum import bill, and a foreign exchange crisis accruing due to the collapse of the Bretton Woods System of fixed exchange rates in 1971. Wholesale Price Index (WPI) inflation in India shot up five times between 1971-72 and 1973-74 — from 5.6 per cent to 25.20 per cent.

All the glamour of the Green Revolution, which, in 1967, envisaged transforming India from being a “begging bowl” to “bread basket”, was wearing off.

Then-Home Minister YB Chavan hinted that the ‘Green Revolution’ was turning into a ‘Red Revolution’ — what with the outmoded agrarian social structure, excessive soil depletion, and instability. The “complex molecule” of the Indian village was about to “end in an explosion”.

Indira Gandhi’s over-optimism reached its peak.

“The buoyant government decided to fulfil its promise to halt foodgrain imports from the United States, an ego‐boost to a nation embarrassed by its perennially needy condition,” wrote The New York Times on 18 March 1973. “India, always on the verge of hunger, always at the whim of nature, faces a critical food shortage.”

Food scarcity was once again a growing concern. Wheat output declined from 26.4 million tonnes in 1971-72 to 21.8 million tonnes in 1973-74. Food shortage fear abounded — hoarding added to the mounting crisis.

In a small Gujarat village, the mother of a 3‐year‐old boy reportedly shrieked at an Indian journalist: “Why don’t you take his photograph? He has not seen or tasted sugar in his life.”

But for many critics, the economics of the wheat trade was always secondary to the politics of it.

“It was a complete disaster. Politics was the main reason why she nationalised it, not economics. The optics were remarkable – ‘She has done it!’” said former Chief Economic Adviser Ashok Lahiri. “I’d be surprised if people like [former RBI Governors] LK Jha and IG Patel didn’t sound a word of caution. But politics is ultimately supreme. If the PM wants to do something…”

Foodgrain nationalisation ultimately failed because the Indian government was so poorly equipped to handle the trade — and like its ad hoc takeovers of banks, insurance, and coal, it used the same formula for food. The policy had become a knee-jerk reaction for the Congress.

“Politicians cannot be seen as inactive. The first attack is always on the middlemen and traders to ask them to sell cheaper. We saw this in Bengal too. When vegetable prices went up, the government said that they will conduct raids and see how black markets work. The next is a very dramatic thing — nationalisation,” said Lahiri.

Everybody thought “Ab sasta ho jayega (Now it will get cheaper)”, and Indira Gandhi believed there would be no hoarding anymore.

Lahiri also said the that “fear of shortage… is such a risky thing”, adding that “[Nationalisation] proved counterproductive, added to inflationary expectations, and strengthened hoarding.”

And though the government appeared to store grains for a rainy day ahead, it was nothing but a laissez-faire affair.

“The storage cost is enormous. Most of the time, speculators or traders did it, and they acknowledged that there was a risk involved. If you leave it to bureaucrats, it’s not his money, if you leave it to a politician, it’s not his money. That kind of calculation is speculation that I would not like to leave to the government,” he said. “Because a mistake can be costly, and there are no costs for politicians.”

The Indira Gandhi government lacked the machinery to ensure smooth trade. “There was a refusal to accept reality — you don’t have what it takes to run it. Think of the touchpoints for wheat,” said Lahiri. “How many places do you have to sell it? Look at the fair price shops now. How will you ensure that they’re not doing hanky-panky? Look at the government’s procurement policy now. Is it working smoothly? Is it corruption-free? What about the handling costs of the FCI?”

The question should not have been around nationalisation, according to Ramakumar. “The government should have gone for more substantial and meaningful control of trade rather than nationalisation, because capacity was the big question,” he said.

But for the Indian government at the time, nationalisation was one way to plug the leaks. “The government should be pragmatic and have a fairly good idea about its capabilities. Just because some people are asking for it, it would be foolhardy to say: I’m going for it. Indira Gandhi had to relent. And thank god she relented, ” said Lahiri.

The sentiment of appealing to the public was tied to the legislations Indira Gandhi had introduced in previous years. Lahiri drew comparisons to Indira’s push for the abolition of privy purses. When a Planning Commission member asked her “why she was making so much song and dance about such a paltry gain”, with her iconic smile, she explained: “What the state gained in material terms was secondary to the political gains”.

The sentiment against Indira Gandhi’s “politics-above-all” formula still pinches critics today.

“Everything she did was politics. That it was ideological isn’t true. The nationalisation was good in cutting off the funding of the Jana Sangh, which was supported by traders and businessmen,” said retired businessman Jaithirth Rao. “From banks to insurance to coal and then to grain — the nationalisation got her a lot of support from pro-Soviet members like D.P. Dhar and Nurul Hassan in her kitchen cabinet.”

Ultimately, the “song and dance” about nationalising everything became a tool to expand the Congress’ resources — the popular appeal of nationalisations was such that “the public sector could be milked for patronage”, according to Rao. “Grain trade tells you that she was not like Mao or Stalin, who would go ahead even if people were dying. She was very pragmatic — when she saw there was too much opposition, she backed out.”

And if the Left would see itself defeated a year later, the Right was brought to its knees, too. As were businesses, said Rao.

“Minoo Masani, the Tatas, were all supine. We had all given up — a beaten lot,” he added.

A cautionary tale

The nationalisation policy was withdrawn in March 1974.

The Minister of Agriculture, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed said that the government would henceforth allow wholesalers to operate under a system of licensing and control. It was easily forgotten at the national level, blending into crisis after crisis during the 1970s.

“Those who were concerned about cartelisation and monopoly power of big traders and their exploitation of small farmers and consumers wanted public control over grain trade,” said Pranab Bardhan, professor emeritus of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. “On the other hand, those who were worried about public bureaucrats messing up the traditional channels of agricultural marketing were against state takeover.”

While the policy was a disaster, it laid bare issues of food security in India — and became a cautionary tale.

“Indian policies have always assumed that the agriculture sector is corrupt,” said Krishnamurthy. “The inherent suspicion in Indian policy comes from colonial and post-colonial times.”

This paranoia is evident in the way in which Gandhi and Dhar viewed private traders. But in reality, the real damage was being done in the distribution sector — another colonial import.

“You can’t have a poor economy without having a PDS, as we saw during the British Raj with massive famines,” said economist Prabhat Patnaik. “In fact, the British introduced PDS after such famines, which is like closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.”

It showed the importance of a reliable, efficient state mechanism to support sudden policy decisions — a lesson echoed in the chaos following the sudden decision to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 banknotes.

But things are more complicated when it comes to food security, which is dependent on a range of extraneous factors that economic policy cannot control. Plus, heavy-handed state action like taking control of the markets couldn’t maintain food circulation.

Drawing parallels with the Narendra Modi government’s actions, Krishnamurthy pointed to the repeal of the farm laws.

The contrast is glaring, though the outcome was similar: Indira Gandhi tried to edge out private players and failed, while PM Modi tried to bring in private players through the now-repealed farm laws and also failed.

“The corollary of nationalisation of the grain trade in the 1970s is the push for drastic deregulation of agricultural markets across Indian states, which we saw epitomised in the 2020 farm laws, which similarly were central laws brought into effect in what had long been agreed was a state subject (agricultural marketing)” said Krishnamurthy.

“But although in the opposite direction, they were fiercely resisted and contested as well, and had to be withdrawn.”

It seems that deregulation has remained a tricky job for the Indian government.

“Heavy-handed actions, whether to seize control of markets or to dramatically deregulate them in such a complex and diverse sector of economic life and livelihood are inevitably unsustainable, but finding the right balance and negotiating its implementation has never been easy” she added, noting that several BJP-ruled states had made “incremental changes” to their laws prior to the 2020 farm laws.

The unfortunate thing is that no matter the acerbic criticism against Indira Gandhi’s nationalisation of wheat trade, it hasn’t made for a lesson in economics.

“A PDS is central and essential, otherwise you’d be back in colonial times,” said Patnaik. “It’s interesting that the Modi government has been making the same mistakes. Back then the government had food stocks and sold them in the open market, traders gobbled them up and hoarded the grains. Such stock has to be disgorged through the PDS and not the open market.”

The Modi government, he added, “hasn’t learned anything from history”.

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Soviet Midas touch drove Indian economy during Cold War. India rekindling rupee-rouble affair