Like many of the low-budget late-Stalinist office blocks in New Delhi, the headquarters of the Research and Analysis Wing seem more appropriate for the austere penances of Buddhism: Light and air are walled off by concrete, discouraging conversation in the endless, dank corridors. An elevator leads foreign dignitaries directly to the commodious top-floor offices of the organisation’s head, known only as the ‘Secretary R’. Light washes over the elegant hardwood furniture and sink-in settees, suitable for elevated conversation.

The story that Vishal Bhardwaj’s hit film, Khufiya, has now told to Indians began under the uncertain illumination of a tube light in one of these corridors in late 2003.

Khufiya touches on the penetration of R&AW. Loosely based on Amar Bhushan’s own thinly fictionalised 2012 book Escape to Nowhere, the film has Tabu, helped by the spy’s fictional alter-ego Jeev, hunt down the mole in R&AW and exact vengeance. The reel-world denouement, though, was quite different from the real-world ending.

“We should be sending each other our UOs,” South-East Asia desk head Major Rabinder Singh, a one-time Army officer, casually told the tall, young officer working on China. “We’re all working for the same thing, after all,” Singh reasoned. “And we should have some idea of what other people in the organisation are thinking.”

The UO, or unofficial note, is the opinion article of the intelligence world, containing unsigned policy suggestions, observations, and sometimes, ruminations. To a dedicated reader—and there have been few at the highest levels of government—the UOs would give a sense of what R&AW’s desks thought the government ought to be doing.

In itself, the idea of information-sharing was not heretical. Large numbers of foreign intelligence services encourage such sharing.

Rana Banerjee, R&AW’s highly-regarded expert on the Pakistani military, had said he saw no harm in Singh’s proposal, three officers familiar with the case have told ThePrint. There was no classified operational intelligence in a UO, Banerjee reasoned.

To the young 1990-batch Allied Services officer S Chandrashekhar, who now heads an élite cyber law consultancy in Gurugram, something seemed off. Like old Eastern bloc intelligence services, R&AW was, and is, highly compartmentalised. The institutional culture of the organisation did not encourage casual conversation in the corridors. Singh had no business asking to know someone else’s business.

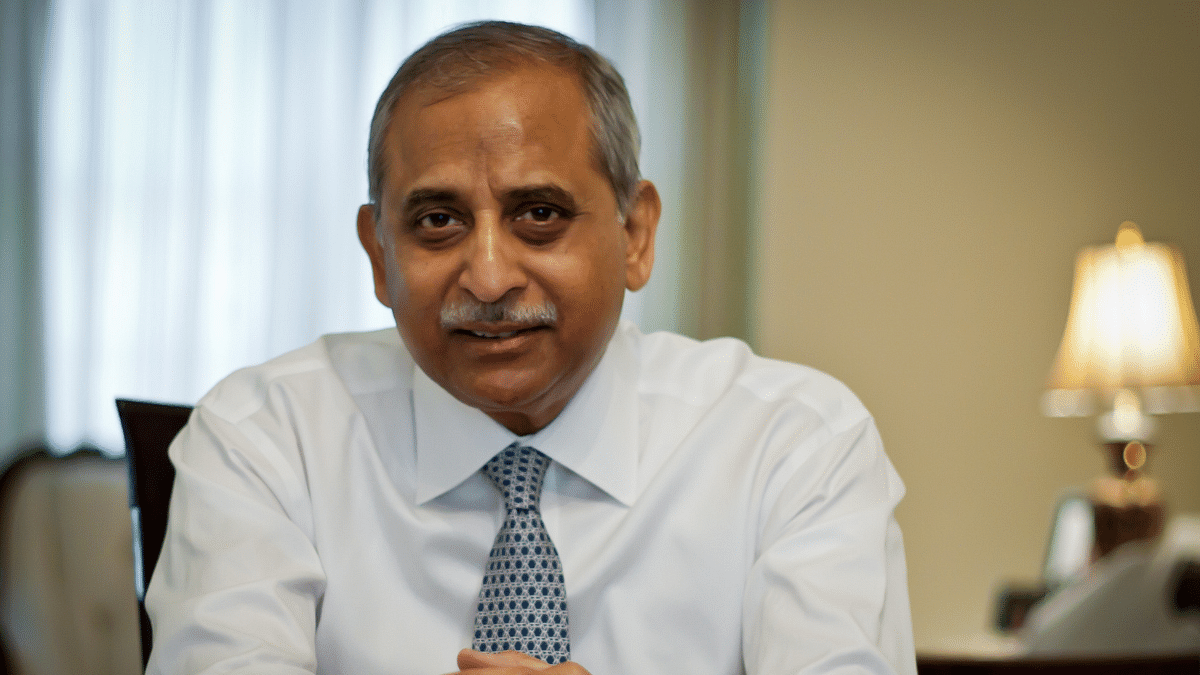

Chandrashekhar walked down the corridor right after the conversation, past the office of his own boss, Tilak Devasher, now the author of several reputed scholarly works on Pakistan’s Pashtun heartland. He asked for and got an appointment with Amar Bhushan, the third-most important officer in R&AW at the time, responsible for the organisation’s security.

The biggest spy scandal in R&AW’s history was about to blow up, revealing ugly personality feuds in its chain of command, weaknesses in its organisational structures, and dysfunctional crisis management systems.

Exactly how much the agency learned from the crisis is unclear. Intelligence shared by the United States-led Five Eyes alliance, which made Canada allege India’s involvement in the assassination of pro-Khalistan activist Hardeep Nijjar, shows poor communication security and practices. Following its failure to detect the Indian nuclear tests of 1998, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) sought to penetrate R&AW—probably why it recruited Singh.

Today, it’s clear that friends still spy on friends—and there’s no guarantee that R&AW is more hardened now than in the past.

Also read: ‘Air India ki flight mat lo’ — how Canadian neglect led up to Kanishka bombing 38 yrs ago

All excellent chaps

Like so much of India’s upper middle class, Singh had one foot in the West. His parents, belonging to landed Punjabi families, had emigrated to the US. They adopted Singh’s son so the latter could acquire citizenship in that country. His wife, Parminder Kaur, had worked for United States Agency For International Development (USAID). The couple owned a four-bedroom home on Chakrabarti Vithi in New Delhi’s Defence Colony, living in circumstances far more affluent than their services peers.

He seemed like a good enough chap..Not the brightest chap, but pleasant company, recalls an officer whom Singh hosted for dinner twice on his visits home from an East Asian capital.

After meeting Chandrashekhar that day in 2003, Bhushan set up a team to investigate Singh. Tightly controlled, the team often operated from Bhushan’s home. Early breakthroughs in the case emerged from Chandrashekhar, who was able to establish that Singh had no contact with CIA personnel or their contacts in India.

But that wasn’t so. Singh used to electronically send all UOs and other material he gathered through an encrypted fax machine that was run through the personal computer in his home. Though the team found no evidence that critical national secrets had been obtained by Singh, the major was providing his handlers with an overview of Indian intelligence operations and priorities across the world.

Later investigation, an R&AW officer familiar with the case said, found no evidence that Singh received payoffs from the CIA, though the agency could not investigate any transactions that might have been made overseas. There was no system then for periodic vetting of officers with families overseas. Indeed, many military, intelligence, and civilian officers even today have close links with the diaspora.

The investigators also explored the possibility that Singh might have had a personal grievance. Sikh families in Defence Colony had been attacked in the 1984 violence. Again, the investigators drew a dead end.

For weeks, R&AW’s in-house counter-intelligence team monitored Singh’s movements, down to his visits to the gym. The suspected spy’s office, home, and car were bugged, and his telephone lines tapped. A surveillance camera was fitted in the air-conditioning duct that ran through his office, so the documents he photocopied could be monitored.

Chandrashekhar played a key role, offering Singh exactly the kind of material he had been looking for. Singh was fed genuine but dated cipher traffic generated by the US’ mission in Islamabad, which R&AW signals intelligence personnel had intercepted. Singh was told that a computer hacker in Brazil had offered to sell this data to India for $100,000 — and he confirmed suspicions about his conduct by promptly seeking more information.

Like all intelligence services, R&AW hoped to run its surveillance operation for as long as possible to learn as much as possible about Singh’s treason and find evidence of exactly who he was working for. This, however, was where things began to unravel.

The complex personal relationships between R&AW’s top three officers at the time, many insiders believe, had something to do with what transpired. Bhushan, Jyoti Sinha, who was responsible for India’s near-neighbourhood, and CD Sahay, R&AW chief, were all 1969-batch officers of the Indian Police Service’s (IPS) Bihar cadre. Though they enjoyed a close personal relationship, often meeting at the Delhi Golf Club and each others’ homes, there were also intense personal rivalries.

Exactly how much Bhushan told Sahay about the progress of the case, as he mounted surveillance on Singh, remains a matter of dispute. In normal circumstances, the Intelligence Bureau’s (IB) counter-intelligence team, which has extensive experience in cases of this kind, should have been called in to handle the case. Bhushan’s book suggests Sahay decided against calling in the IB.

The surveillance operation climaxed amid bizarre circumstances in mid-2014.

R&AW watchers decided to stop Singh from removing 13 classified documents from his office. To avoid Singh getting suspicious, the entire R&AW staff was searched as it left the building. “Long queues of staff built up at the exit gates,” one officer recalled. “And staff from adjoining offices in the Central Government Office complex came to gawp.”

Like any sane spy, Singh did panic. Later that night, the R&AW surveillance team watched as he parked his car near the market in Defence Colony. The team parked a short distance away, waiting to reemerge. Singh had, however, activated the prearranged distress signal that told the CIA station in Delhi that he was about to be compromised. Leaving the market in another car, he disappeared.

Also read: Take care, Rajiv Gandhi told Prabhakaran. Even gave bulletproof vest before Sri Lanka Accord

Leaking secrets

The idea that foreign intelligence services were seeking to penetrate R&AW wasn’t a surprise. Former 1962-batch IPS officer KV Unnikrishnan was arrested in 1987 and held in Tihar Jail under the National Security Act (NSA). According to R&AW counter-intelligence, Unnikrishnan, a key figure in the agency’s communication with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), had become close to a CIA officer stationed in Colombo and often went drinking with him.

Early in 1987, R&AW claimed, Unnikrishnan received a message from an air hostess visiting Bombay, referencing their common friend, the CIA officer. Unnikrishnan allegedly travelled to the city to visit the woman. Their sexual liaison was photographed, enabling the CIA to blackmail him.

Although Unnikrishnan served 18 months under the NSA, no prosecution was brought. R&AW claims the decision was made because a trial would have meant publicly exposing its training of LTTE terrorists. The officer’s daughter, an international-level athlete, now lives in the US.

There were several, less-spectacular cases of possible compromise, though never conclusively established. Shamsher Singh Maharajkumar, an ex-IPS officer posted in Islamabad, Bangkok, and Canada, let R&AW know he intended to stay on in Canada with his son at the end of his service. Sikander Lal Malik, secretary to R&AW founder RN Kao, chose to stay on in the US at the end of his service in circumstances that remain unclear. MS Sehgal, secretary to former R&AW chief Girish Saxena, remained in London.

Ashok Sathe, once in-charge of the R&AW station in Khurramshahr in Iran is said to be living in California, while NY Bhaskar and BR Bacchar both secured residency in the US. Major RS Soni moved to Canada without notifying R&AW.

R&AW wasn’t the only service to be targeted either. In 2006, the Delhi Police arrested SS Paul, a computer systems operator at the National Security Council (NSC) secretariat, on charges of espionage. The IB believed that Paul had passed on NSC documents to Rosanna Minchew, a CIA operative working undercover as a third secretary at the US embassy in New Delhi.

Paul is thought to have been introduced to Minchew by Mukesh Saini, a former naval officer who left the NSC to join a multinational corporation. Saini was involved in the India-US Cyber Security Forum, a body set up in 2002 that included representatives of R&AW, IB, Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence.

Every intelligence agency around the world has suffered similar embarrassments: Enemies and friends both make for competent adversaries.

At the outset of the Cold War, Lieutenant-Colonel David de Crespigny Smiley—swashbuckling volunteer in the Somaliland Camel Corps, veteran of a plot that unseated the King of Iraq, comrade to guerrillas in Siam and Greece, and liberator of 4,000 prisoners of the Japanese, all “absolutely stark naked”—set up a secret army to take on the communist leader Enver Hoxha’s regime in Albania.

Few of the 200 agents sent in would survive: Betrayed by the Cambridge-educated double agent Kim Philby, the Albanians knew of each infiltration, down to the drop zone. The covert war intended to tear apart the Iron Curtain had not begun well, historian Ben Wallace records.

Eight spies at the heart of the US’ nuclear programme, similarly, kept the Soviet Union on top of progress in developing atomic weapons and eventually helped push start its own plan. Elaborate attempts by the CIA to tunnel under Berlin, and tap Soviet communications traffic, were also betrayed. For years, the tunnel taps were used by the Soviets to feed deliberate disinformation to the West.

Likewise, the West cultivated assets at the top of the Soviet KGB. Oleg Gordievsky, eventually spirited out of the Soviet Union in 1985, provided high-level information on the KGB’s spy rings in the West and the political mood in the Kremlin.

The escape

The little that’s become known about Rabinder Singh’s escape emerged because of painstaking work by R&AW’s Kathmandu station, which, like others in the neighbourhood, was not notified either of the existence of the mole or his escape from Delhi. Singh and his wife, R&AW’s Kathmandu station later discovered, crossed into Nepal through the Nepalganj border on 1 May. They were hand-delivered US passports by CIA station chief David Vacala at their hotel room, bearing the names of Rajpal Prasad Sharma and Deepa Kumar Sharma.

The man in charge of putting together these details, though, was bypassed after the case and denied the opportunity to head R&AW. Like his brother, Lieutenant General SK Sinha, who resigned when bypassed for the post of Army chief in 1983, Jyoti Sinha put in his papers.

The doyen of South Asian Studies in the US, Steven Cohen, told another Washington DC-based scholar that Singh approached him for a job around 2010. “I spoke to him for some time, and decided he wasn’t a genius,” the scholar recalls Cohen joking. “So, I pointed him down the road to the RAND Corporation down the street.”

Singh was finally reported to have died in a road accident near Maryland in 2016, but there is no documentation recording an accident either under his name or that of Rajpal Sharma.

For many within the intelligence community, the biggest questions in the R&AW case have to do with whether he was deliberately allowed to escape. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government, on the eve of an election, would have been hurt hard by revelations of penetration of R&AW by an agent of a country it had carefully cultivated relations with. The Manmohan Singh government, elected to office in its place, had no reason to damage relations with the US by making public the story.

An authoritative telling of the story isn’t, in fairness, easy. Even though former Internal Security Advisor MK Narayanan reviewed the case in 2005, listening to over 700 hours of internal audiotape, and questioning each officer involved for hours, his findings were never published. Narayanan brought in IPS officer PK Hormese Tharakan to clean up the mess. Files of old R&AW officers suspected of treason formed the core of Narayanan’s case — that the organisation needed more IPS officers like the IB.

None of the handful of surviving officers directly involved agreed to discuss the case on record with ThePrint, pointing to recently amended rules that threaten to withdraw their pensions should they reveal information gathered during their service. Brigadier VK Singh, a former Army officer who served in R&AW, is being prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act for a book he published in 2007.

The one account we have is Amar Bhushan’s, more protestation of innocence than mea culpa.

The one account we have is Amar Bhushan’s, more protestation of innocence than mea culpa.

An uncertain future

Founded out of the ruins of the war of 1962, when the IB’s assessment and intelligence-gathering capabilities were brutally exposed, R&AW has a long history of success. The organisation played a key role in organising the Mukti Bahini in 1970, laying the foundation for the successful war to liberate Bangladesh. It harried the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Directorate in Punjab, organising tit-for-tat bombings during the Khalistan movement. It engineered the rise of pro-India regimes in Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Is R&AW now more robust than in the past? Have the right lessons been learned from the Rabinder Singh case? The IPS-driven organisation that emerged in the wake of this case, many argue, is fundamentally unsuited for foreign intelligence gathering, which involves language and regional specialisation cultivated over decades.

In the wake of the Kargil War, a committee led by former Jammu and Kashmir Governor Girish Saxena called on the covert services to take “an honest and in-depth stock of their present intelligence effort and capabilities to meet challenges and problems”. The committee’s classified 244-page report perceptively noted: “A generalist administration culture would appear to permeate the intelligence field.”

The Saxena Committee, of which Narayanan was a member, also pointed to serious deficiencies in the collection, reportage, collation and assessment of intelligence. It noted the need for the covert services to recruit area specialists, linguists, and a wide spectrum of technical experts. Little effort, though, has been made to act on these recommendations.

Even though many lessons have been learned within the R&AW since the Rabinder Singh case, the Nijjar case has underlined that severe vulnerabilities remain. For one, the growing use of offensive surveillance tools like Pegasus and Predator—used to gather intelligence against domestic dissidents, foreign diplomats, and terrorists alike—allows Western intelligence services to detect weaknesses in India’s cyber networks and monitor its traffic.

A growing culture of offensive operations of the kind Khufiya celebrates, moreover, hasn’t always been matched by operational competence. The botched attempt to kidnap fugitive businessman Mehul Choksi from Antigua led to revelations that Indian nationals were involved in the operation. Police investigations in Antigua are also reported to have identified one conspirator as Gurdip Bath, a St. Kitts diplomat with close links to India’s political establishment.

In 1948, the US government created a new Office of Special Projects within the CIA to conduct covert action across the world. The Office’s tasks, according to a National Security Council directive, were activities “conducted or sponsored by this government against hostile foreign states or groups or in support of friendly foreign states or groups”. In practice, this meant funding anti-communist forces, including former fascists in countries like Italy and even assassinating leaders whom the US found hostile.

There was one key caveat in the directive: Covert action had to be “so planned and executed that any US government responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorised persons and that if uncovered the US government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them”.

The cases of Kulbhushan Jadhav and eight former Indian naval officers sentenced to death in Qatar for espionage underline the tragic consequences of intelligence ambition not being matched by tradecraft.

Lacking a system of archival disclosure, and with an anaemic tradition of scholarship on intelligence, India is losing the ability to learn from its mistakes.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)