The year 1967 changed Indian elections.

For the first time in independent India’s history, the Congress Party had been exposed as weak: And this set off a chain of reactions in Indian politics. It would be the event that triggered the end of simultaneous elections, and the start of coalition politics.

During the 1967 general elections, the Congress won at the national level—but barely. Far more significantly, it lost in nine states.

It was a shock. It marked a clear before-and-after moment in Indian politics. Before this, independent India had only known one party, one government, one central figure. And Indira Gandhi hadn’t yet become who she would become.

After 1967, election cycles in India were never the same. India entered an unprecedented phase of political diversity. And it is coming full circle in 2023. The elections led to the formation of the first multiparty coalition—the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal (SVD)—that came to power in the states that the Congress had lost.

Much like INDIA, a coalition of 28 parties in opposition to the ruling BJP, the SVD was cobbled together from multiple parties across ideological lines—except then, the common enemy was the Congress.

Today, the pre-1967 election cycle is presented as a Golden Era and the Narendra Modi government wants to bring it back in the name of cost-cutting, efficiency and policy predictability. But the nostalgia is misplaced and spurious, many say.

The political template of the first two decades of independent India was buried under “Anti-Congressism.” And the cycle of concurrent elections was shelved, which today is finding more popular currency—with five states going to the polls in the next two months and a general election looming, the demand for “One Nation One Election” is back in the spotlight.

But history shows why copy-pasting that format out of nostalgia isn’t necessarily a good idea.

“This period is presented as if it [One Nation, One Election] was a constitutionally mandated system,” said psephologist and politician Yogendra Yadav. “But it isn’t. In those days, the state elections were held along with the Lok Sabha election. Not because it was a constitutional imperative; it’s just that the calendar happened to coincide. The parliamentary system in India in fact assumes that the calendar will diverge sooner or later—it had already happened in Kerala,” he said, referring to the first assembly elections in the state that elected a short-lived, quickly-dismissed Communist government under EMS Namboodiripad.

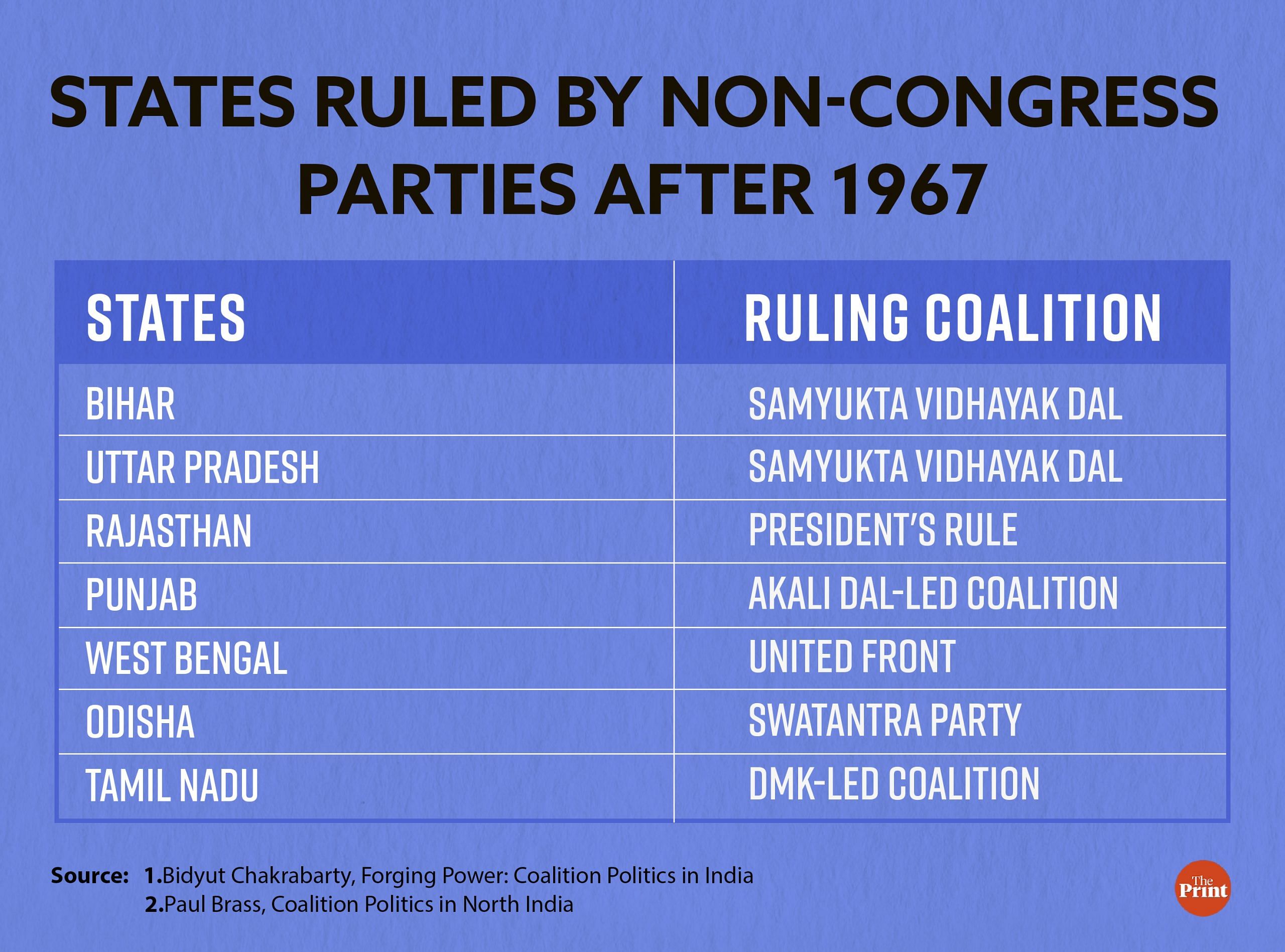

There are myriad reasons why the system came to a grinding halt after 1967. Barring Kerala, the coalition governments that came up in the other eight states that the Congress lost—Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, West Bengal, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu—would also crumble, forcing the states to hold elections again.

This was how the cycle broke, and has continued since. The argument presented in favour of going back to the pre-1967 election cycle, therefore, is misleading.

“Trying to fit Indian politics into a rigid mould is useless. Simultaneous elections in the first 15 years of India’s political history were a simple coincidence. An artificial coincidence. It was like an incubation period,” said Yadav.

The efficiency paradigm during the first 15 years of electoral politics in India lacked competitive democracy because the Congress was always in power—which is why the cycle was broken with an all-new, ideologically diluted coalition.

“Rather than making a virtue of non-concurrent elections, it is more accurate to say that there is no virtue in concurrent elections necessarily,” said political analyst Suhas Palshikar, who taught political science at Savitribai Phule Pune University and is chief editor of the journal Studies in Indian Politics. It was simply the functioning of competitive politics that broke the cycle of simultaneous elections.

Also Read: How Modi’s ‘One Nation, One Election’ panel spurred INDIA alliance to form its own committees

‘Anti-incumbency’ and the incubation period

The Congress had never lost an election before 1967—and no one knew how to proceed.

The party had to stand down only twice before: Kerala had gone for a Communist government in 1957 under EMS Namboodiripad, which was dismissed in 1959. The Congress had also shared power in Odisha in 1957 with the right-wing party Ganatantra Parishad.

But it had never been decimated until 1967.

So when veteran farmers’ leader Chaudhary Charan Singh crossed the Parliament floor with 17 MLAs to break ranks with the Congress, it sent further shockwaves across the rubble of electoral politics. Indira Gandhi’s emissaries tried to coax him back into the Congress, offering him the position of Uttar Pradesh’s chief minister. But that ship had sailed.

Singh had made up his mind. It was time to leave the Congress, and it was the right time to strike.

He was fed up with rampant corruption within the party and felt it had lost touch with the Indian public. His disagreement with the political juggernaut was widening the cracks within the party. The cracks would widen and widen until the nation’s electoral make-up, so far joined at the central level, would come apart too.

“The real opposition came from inside Parliament. Congress’ own ideology wasn’t very well defined—communist and socialist leaders grew very strong within the party,” said Rasheed Kidwai, political analyst and author of 24 Akbar Road: A Short History of the People behind the Fall and Rise of the Congress.

In that respect, Kidwai sees a strong similarity between 1967 and 2023—a dominant party at the helm, and a politics that’s bringing oddballs of opposition together.

“The Congress performed both functions—it was the ruling party and the opposition as well,” said Yadav. And it was the shaky party ideology that paved the way for the electoral shock that would come in 1967.

The election was also a landmark event for caste politics in India. For the first time in the two decades of India’s incubation period, popular leaders who’d been sidelined by the Congress—like Charan Singh—decided to form their own governments in states where the Congress had lost. And they were chipping away at the influence and power that Congress wielded.

Simultaneous elections in the first 15 years of India’s political history were a simple coincidence. An artificial coincidence. It was like an incubation period

– Yogendra Yadav, psephologist and politician

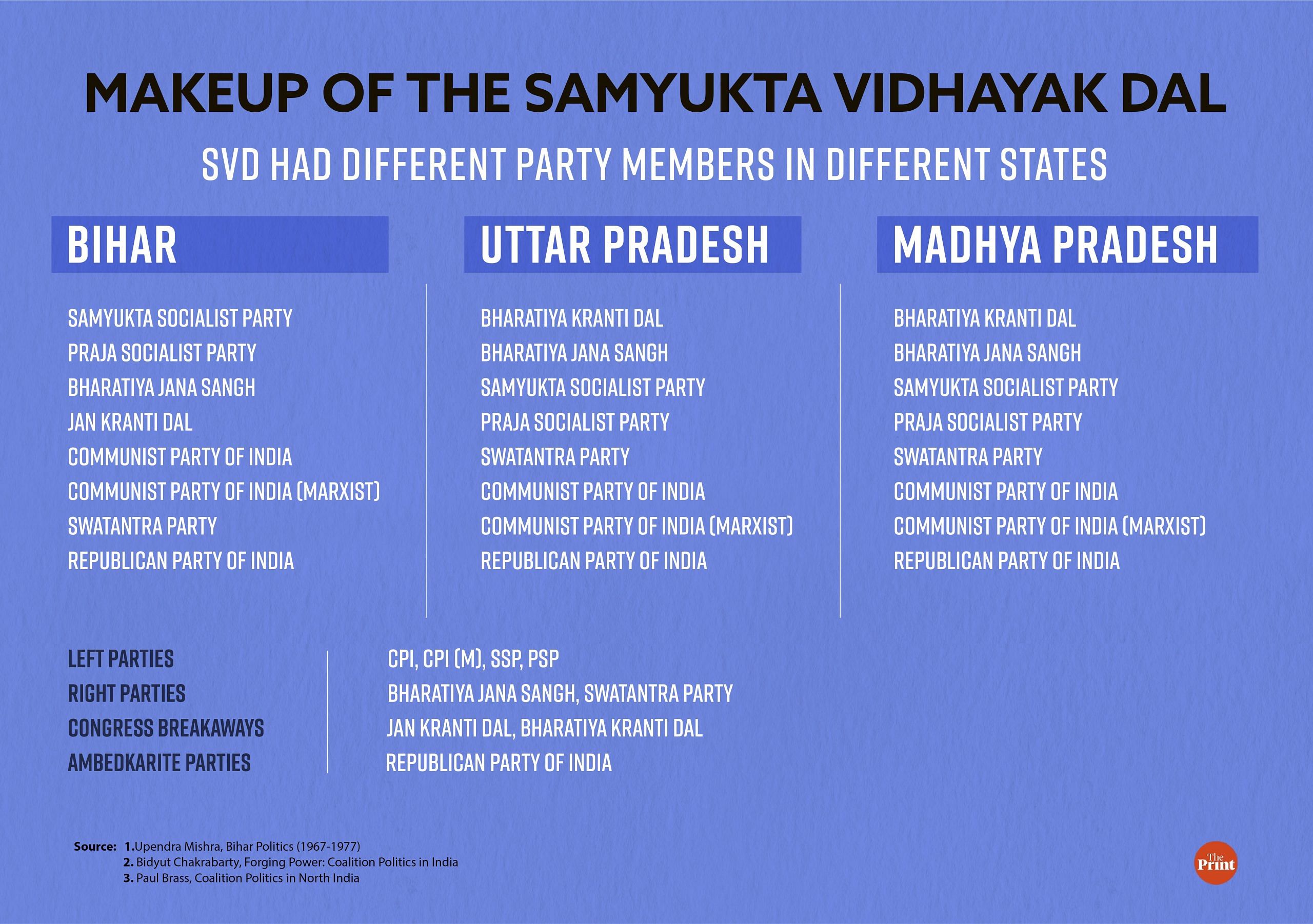

What rose out of the rubble was the SVD, an unlikely ragtag coalition of parties that formed the government in the north-Indian states. It was made up of the Bharatiya Kranti Dal, the Samyukta Socialist Party, the Praja Socialist Party, the Jana Sangh, and the Communist Party of India as well as the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

“What is today called ‘anti-incumbency’ had set in, as corruption had become the norm,” said Yadav.

Besides, the country had undergone serious crises. The 1962 and 1965 wars wreaked havoc on its economy, the famine years that followed worsened it, and the power vacuum due to Nehru’s death made the uncertainty starker. India stopped the Five Year Plan officially, reasoning “forget five years, they had to survive for one”. And then would come the 1967 election, which would shake up what many today call the “Congress system”. Indira Gandhi was not the formidable figure she was in the 1970s—she was still seen as the “gungi gudiya”, a political novice who hadn’t yet found her footing, or voice.

She was still unpopular after her 1966 bank nationalisation measure, and even the Congress was splitting hairs between her and Morarji Desai. In fact, when she was campaigning in Bhubaneswar in February 1967, right before the elections, a stone was thrown at her, giving her a bloody nose and a split upper lip. Officials tried to shield her, and her aides tried to take her off-stage.

But she took out a handkerchief from her handbag to wipe her bloody nose, and she continued her speech valiantly, earning cheers from the crowd.

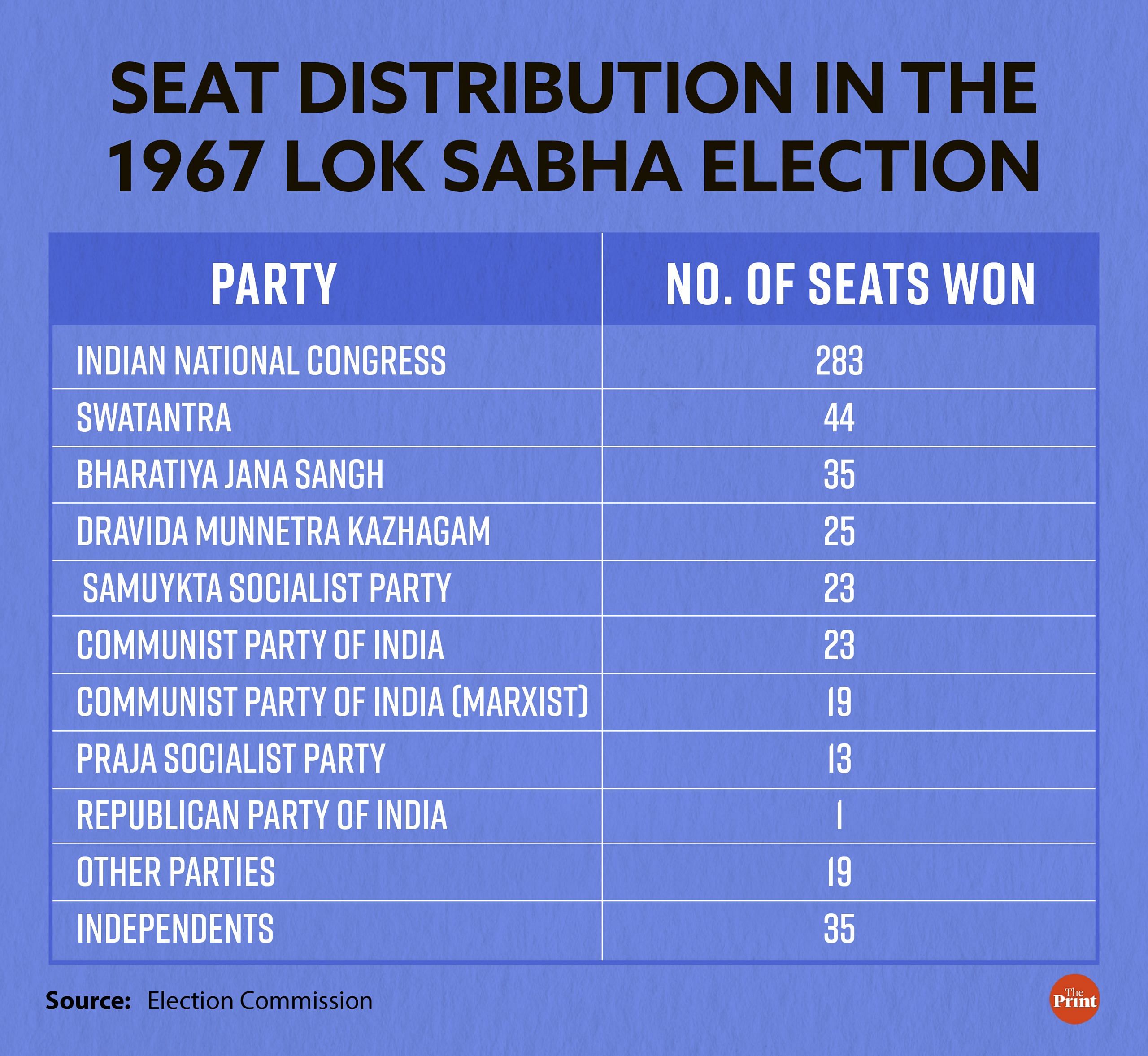

Although the Congress had won the general elections, the vote share of the party had substantially declined. In 1962, i.e. 3rd Lok Sabha elections and also Nehru’s last election, the Congress secured a vote share of 44 per cent, winning 361 out of the 494 seats.

In 1967, the vote share of Congress decreased to 40.78 per cent, with a marginal majority of 281 out of 523 seats in Lok Sabha. Indira Gandhi was sworn in as the Prime Minister of the freshly elected—but massively weakened—assembly.

In an article in 1967, noted journalist Hrinmay Kalrekar—then a student at Harvard—stated that the key reasons for Congress’ slide were food shortages, the depreciation of the rupee, and the perception that the government was submitting to Western pressures. He also mentioned how the party’s culture has come back to haunt it.

The other factor at play was the emergence of regional parties: Parties like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, and the Akali Dal had garnered popularity. Gandhi was fending off criticism from veterans like Charan Singh who had spent decades with the Congress, and was also up against the rise of several new parties.

The rise of these regional parties as a combined force bidding for power at the Centre is possibly due to two reasons, according to Bidyut Chakrabarty, author of Forging Power: Coalition Politics in India. The first was the decline of the Congress as a dominant party, and the second was that new social groups and caste groups had been introduced to the political process. The Dravidian anti-caste party DMK formed its first government in Tamil Nadu in 1967 too.

“Since the entrenched groups in the dominant party tended to impede their entry to the political processes, these new entrants found it easier to make their debut through non-Congress parties, or occasionally even by founding new parties,” wrote Chakrabarty. This was why so many new parties—so far neglected from sociopolitics, as the Congress was dominated by upper castes—came together across ideological lines.

Indira Gandhi could see what had happened and saw merit in India’s federal structure. When her government was slammed with a no-confidence motion, Gandhi was forced to address Parliament.

“In the last General Elections, governments of many different views emerged. This House is aware that I welcomed the emergence of these governments, I welcomed them publicly, and I welcomed them in my meetings with the Chief Ministers. It was not motivated by any narrow party motivation. I felt confident that our federal system would respond to the changed political situation and, in fact, I did everything I could to discourage any attempt to topple these governments,” she declared emphatically.

She added that allowing these new governments to function properly was a point for democracy.

“Not only I, as the Prime Minister, but I can also speak for all my colleagues,” she continued. “That in their respective departments they did their best to allow these governments not only to function effectively but to help them in every way that they could. Because we believed that in doing so, democracy would be strengthened.”

So 1967 wasn’t just the first time that a coalition like SVD was formed in India, it was also the very first time that people were willing to go for alternatives.

The years between 1952—India’s first elections—and 1967 have limited relevance to the debate over simultaneous elections, according to Palshikar. Electoral politics had just begun in 1952, and therefore all elections were conducted at the same time. But when competition emerged in 1967, the cycle broke and midterm elections were held in states. The competition was in the form of these smaller parties, who came together to oppose the Congress.

“While they didn’t agree on their political programs, they all agreed that Congress was a stumbling block for democratic politics. That’s how the idea of coming together shaped the non-Congress parties,” said Palshikar.

But simply coming together doesn’t solve the issue.

“But since then, one thing seems to be quite clear: Non-dominant parties simply coming together doesn’t help,” added Palshikar. “It’s not just a calculation of how many votes these parties can get. So it doesn’t work in terms of approaching non-dominant parties, whether Congress then or BJP now.”

Also Read: One nation, one election is BJP’s ‘brahmastra’. It wants state contests to be ‘Modi versus who’, too

The curious case of Charan Singh

The story of Charan Singh’s first stint as Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh sums up the problems that arose from the Congress’ loss in 1967 and the subsequent SVD government.

Singh had successfully come to power with the help of the SVD alliance, finally assuming the role of Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh after being sidelined for the likes of Chandra Bhanu Gupta. This disparate “incongruent mixture” of a coalition featured parties from all over the political map, with the Swatantra Party making up the far-right and the CPI(M) part of the far-left.

“The SVD was the first expression of a coalition front—without any experience of running a stable coalition, without understanding each other, and with little understanding of statecraft. They didn’t trust each other,” says Yadav. “These governments were not known for any dramatic policy shifts, except to show that forming a coalition was possible.”

Policy shifts were difficult when there were so many differences within the coalition. In Singh’s case, the principled politician, famed for his pro-farmer and anti-corruption stance, struggled to keep the alliance strong across party lines.

It was not a very happy time in his life, according to his archivist and descendant Harsh Singh Lohit.

One such incident is from when Indira Gandhi visited Uttar Pradesh in January 1968, just a month before his government collapsed. One of his coalition members, the famous freedom fighter Raj Narain—who would go on to win the electoral malpractice case against Gandhi which would lead to her disqualification as an MP and the Emergency in 1975—decided to protest her visit. This was unacceptable to Singh, who did not think it proper to protest a visit by the incumbent Prime Minister.

So he arrested Narain at the public protest, angering his coalition partners.

But there were other fissures too, according to American political scientist Paul Brass, whose seminal work is a three-volume political history of northern India, including a biography of Charan Singh. The leaders of the Opposition could not come to a consensus on various issues which led to differences in the coalition. Regional parties that were a part of the coalition also started to venture into their respective states independently.

When there is a dominant party and leader who is very difficult to beat, varying political ideologies come together.

– Rasheed Kidwai, political analyst

The party that held more seats than the Samyukta Socialist Party and Charan Singh’s Bharatiya Kranti Dal was the Jana Sangh, whose leaders were open in their disagreement with the linguistic goals of Muslim leaders like Swatantra’s Akhtar Ali to make Urdu the second principal language in UP.

The SVD coalition gave “some importance” to this dichotomy but its main policy achievements were in short-term agriculture and tax issues, before impasses and infighting between the polarised ideological groups took over. Land revenue was a major wedge issue for the Samyukta Socialist Party and CPI (M) wings, but the short-lived coalition was also plagued by declining support towards an increasingly criticised Singh, who according to Brass, was accused of responding to popular agitations with an iron fist.

The feud between Charan Singh and the SSP finally became public when it decided to undertake an ‘Angrezi Hatao’ (get rid of English) protest, during which two of its ministers were arrested. On 5 January 1968, the SSP withdrew from the coalition. On 17 February 1968, Charan Singh submitted his resignation to Governor Bezawada Gopala Reddy, and President’s rule was established in Uttar Pradesh on 25 February 1968.

Despite its swift death, the coalition’s rise not only represented a watershed moment in the history of Congress’ political hold over India on both national and provincial levels but also created a fork in the road for Indira Gandhi’s then-burgeoning career as she would forge a significant and fractious rivalry with Charan Singh.

What’s more is that new, previously marginalised social groups began to assert their identity, which came to the fore through coalition politics.

Caste became a friction point in 1967 in the same way that it is today, according to Kidwai. From the DMK to Rashtriya Janata Dal to Janata Dal (United), leaders are increasingly asserting themselves, whether in advocating for different social groups or by demanding a caste census.

And just like the INDIA alliance —which includes the INC, JD(U), AAP, CPI(M)—the SVD comprised parties whose ideologies were almost chalk and cheese. The SVD’s goal, in this context alone, seems like an antecedent of INDIA’s anti-Modi agenda.

“When there is a dominant party and leader who is very difficult to beat, varying political ideologies come together. The Jan Sangh & Swatantra Party and socialists had very little in common,” said Kidwai.

Coalitions floundered in other states too

This played out in the other states that the Congress lost too.

The SVD formed governments in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. In Odisha, the Swatantra Party had a majority, but there were plenty of Congress dissidents to support them.

In West Bengal, the communists allied with parties that were at the polar opposite end of the ideological spectrum, with the goal of pushing “pro-people socio-economic programmes”. The Congress had declined here in the mid-60s due to factionalism and food shortage droughts as well as an influx of refugees, industrial strikes, and poor law and order with “recurring riots”. The government that came to power—the United Front—was formed with CPI, CPI(M), Forward Block, Revolutionary Socialist Party and Bangla Congress. There were significant differences in their policies when it came to agriculture, land reform, and education. The death blow finally came when the Bangla Congress exited the coalition. The government collapsed, leading to President’s rule.

While this experimental coalition failed in West Bengal, coalitions survived in Madhya Pradesh—“completing a full term of five years in three different incarnations,” said Chakraborty. The state had two SVD coalitions, followed by a coalition led by the Congress.

The Congress had won the 1967 election with Dwarka Prasad Mishra re-elected as chief minister in Madhya Pradesh, but Govind Narayan Singh led a big breakaway from the party. This breakaway was supported by Vijaya Raje Scindia, who at the time was at the helm of the still-politically powerful Scindia family. Scindia had quit the Congress party and joined the Swatantra Party, which became part of the SVD coalition.

Both Scindia and Singh defected. The government collapsed, and Singh took over as chief minister with a second SVD coalition of 36 ministers. The media had attributed this fall to the personal rivalry between Scindia and Mishra.

Eventually, Singh himself broke from the SVD and returned to the Congress, ending his 21-month term as chief minister. He lost his majority in March 1969, and the Congress took over for the rest of the five-year term.

Bihar had a slightly different story: Here the SVD formed a government with Mahamaya Prasad Sinha of the Jan Kranti Dal (later merged with the Bharatiya Kranti Dal). It was not a stable government—there were plenty of independents entering and exiting the coalition, signalling the defectionary phenomenon from Haryana that came to be called “aaya ram gaya ram”.

This aaya ram gaya ram politics led to three chief ministers succeeding Sinha—for five, 51, and 100 days respectively. And then President’s Rule was imposed until the next election was called in 1969.

“The story of coalition was, therefore, one of both success and failure,” wrote Chakrabarty in Forging Power: Coalition Politics in India. “The 1967 elections were, therefore, a watershed in Indian politics, in the sense that those Assembly polls epitomised a struggle between regionalising and centralising political forces.”

The possibility of One Nation One Election

Any arguments about political stability fall flat in the face of political evolution—how does a large country like India sustain concurrent elections?

On a most basic, emotional level, ‘One Nation One Election’ evokes a nostalgic sense of unity that goes back to pre-1967 India—with a crucial twist, though. This time, it would be ‘Vishwaguru’ PM Modi who’d be tying the country together and not Nehru.

“One Nation, One Election is a very utopian idea. If their (the government’s) idea is to reduce election costs, it’s a misnomer—they’re barking up the wrong tree. Unless we introduce electoral reforms, this idea will serve no purpose,” said Kidwai.

Though the idea may be enticing to those arguing against “communalism, casteism, corruption, and crony capitalism” constantly on the boil due to frequent elections, observers of Indian politics say the model perhaps be best left to the US, Sweden, or South Africa.

“Being a federal republic, every state in India follows its own political course. What is one to do if a particular state witnesses an upturned majority after a few MLAs decide to shift ‘loyalties’?” asked SY Quraishi, 17th Election Commission chief, in his book India’s Experiment With Democracy. To him, the idea of dissolving the Centre if a state assembly disbands—and the whole country going to polls again if Lok Sabha collapses as it did in 1996 within 13 days—goes against the ethos of democracy. And the question of cutting election spending appears to be a tricky one, given that election overspending is a common practice.

Perhaps a perpetual state of elections isn’t too bad, Quraishi said. “Frequent elections at least ensure that they (politicians) show their face to the people regularly. People love election…for the poor, this is the only power they have,” he added.

Besides, by 1971, most states were no longer aligned with the Lok Sabha elections. The one-ness of elections broke. But it did not lead to any political anxiety.

The 1967 elections were, therefore, a watershed in Indian politics, in the sense that those Assembly polls epitomised a struggle between regionalising and centralising political forces.

-Bidyut Chakrabarty, author

In fact, only four states are currently aligned with the Lok Sabha elections—Odisha, Arunachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Sikkim. Only Arunachal Pradesh reportedly favours voting for national parties.

Some data sets and reports across newspapers and journals show that people might prefer to vote for the same party in both Centre and state in case of simultaneous polls—but this doesn’t account for all the various other factors at play.

“Let elections happen according to the cycle of each legislature, because that is what the Constitution mandates,” added Palshikar, pointing to the natural function of each electoral cycle.

Also Read: What’s behind Modi govt’s push for ‘One Nation, One Election’ and why it has rattled INDIA

The constitutional question

The Constitution mandates three things when it comes to forming a government: Each legislature will have a five-year term, the leader of the ruling party at the centre and at the state level has the right to dissolve the legislature if the leader has majority, and—perhaps most importantly—the government can remain in power as long as the legislature has majority, or confidence in the leader.

One of these three has happened multiple times across India’s history, whether in terms of a government being dismissed or a no-confidence motion being introduced. Every legislature has the right to propose a no-confidence motion. If passed, the government is dismissed—and if a new government with a clear-cut majority isn’t formed, elections are called.

What is one to do if a particular state witnesses an upturned majority after a few MLAs decide to shift ‘loyalties’?

-SY Quraishi, 17th Election Commission chief

Ultimately, what happened in 1967 was an expression of fledgling democracy—something captured in the following parliamentary exchange.

Gandhi took to the floor of Parliament to address a no-confidence motion in March 1967.

Bringing up criticism from SA Dange and Ram Manohar Lohia, Gandhi dismissed the Congress Party as being the source of all political suffering.

“The proof is that today, after being in full power, we still have brought this country to a stage where in many States there are Governments of a non-Congress nature, either headed by separate parties or by coalitions,” she said. “This in itself is proof that we do not want to cling to power, that we do not want to act undemocratically.”

“That is in spite of yourselves,” interrupted an unnamed member of Parliament.

“That is not by the grace of the Congress party,” said Bengali politician Samar Guha, from the Praja Socialist Party. “It is due to the Constitution.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)