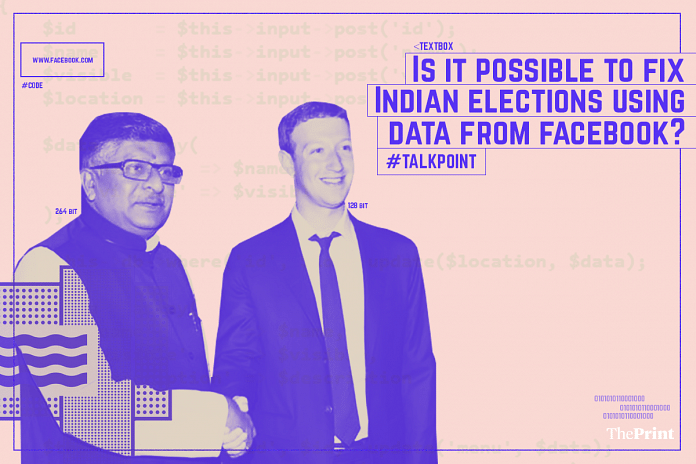

Facebook has been facing heat over the Cambridge Analytica data breach. The company is said to have harvested data to influence Trump’s election and Brexit.

Ravi Shankar Prasad, IT Minister, alleged Congress has ties with the company and asked if Rahul Gandhi supports such methods. On the other hand, Randeep Singh Surjewala, Congress Spokesperson, said it was a lie and it was BJP that has used the firm.

ThePrint asks: Is it possible to fix Indian elections using data from Facebook?

Data can, and will, be used to influence elections unless we act urgently to prevent it

Sunil Abraham

Sunil Abraham

Executive Director, The Centre for Internet and Society

Of course it is possible, because India has no data protection law. Anything Cambridge Analytica does in India will be completely legal, precisely because we lack a legal framework of protection.

We only have ourselves to blame for this. My organisation has been working towards a data protection law for the last eight years. This should be a priority for decision-makers. We had the opportunity to defend ourselves and combat any such drastic situations. Now, it is possibly too late to fix the situation before the next general election.

The Supreme Court, in the Puttaswamy judgment, delivered by a nine-judge bench, said privacy was a fundamental right under the Constitution of India. As a part of that judgment, it directed the government to enact an omnibus data protection law. As a response, the ministry of electronics and information technology constituted a committee under Justice Sri Krishna. The Sri Krishna committee published a white paper, the first draft of which will appear in May or June. The rest is up to the parliamentarians.

Furthermore, India has high rate of illiteracy, both in the classical sense of the term and in the sense of new media illiteracy. Many Indians have been added, in an accelerated fashion, to the internet. They haven’t developed the critical capability to distinguish between facts and lies. Most of India does not speak English and is, thus, unable to configure these platforms to protect their rights. They cannot read the fine print, which enables such companies to harvest their data.

Even if the internet hasn’t percolated entirely through rural India, people do have WhatsApp on their phones and they will act as nodes through which the rest of the population can be influenced. It is through them that propaganda will circulate through offline channels.

Data can, and will, be used to influence elections unless we act urgently to prevent it.

Facebook’s capacity to influence political opinions remains rather limited

Sanjay Kumar

Sanjay Kumar

Director, Centre for Study of Developing Societies

There is hardly any doubt that the number of people using social media in India has increased enormously over the last few years. At present, Facebook is being used by roughly 25 per cent of all Indians, WhatsApp by 29 per cent, and Twitter by 12 per cent.

But I strongly disagree with the idea that Indian elections can be fixed using data from social media. The majority of Indians use social media to stay connected with friends and family members, and only 10 per cent use it actively to send out political messages. Its capacity to influence political opinions remains rather limited.

Also, a large proportion of Indian voters (nearly 60 per cent) vote for the party, and many make up their mind well in advance.

We must also remember that a large section of Indian voters still lives in villages (70 per cent). Many of them use social media, but the capacity of political parties and candidates to influence voters through social media messages alone is very limited. And that is why traditional election campaigns — rallies, road shows, padyatras, etc — remain the preferred choice. According to a survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies during the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, while 20 per cent of the voters said they were approached by political parties via SMS and/or phone calls, nearly 30 per cent mentioned having participated in campaign rallies. The mode of campaign is changing, and social media has begun to play an important role, but it is still far from being a game changer.

Relying on social media data for election trends in India would only be armchair analysis

Osama Manzar

Osama Manzar

Founder-Director, Digital Empowerment Foundation

Social media platforms are like echo chambers, only louder and noisier; and deriving data from social media to analyse election trends or results, especially in India, could be disastrous.

Let me explain why. In India, internet at best reaches 30 per cent of the population, mostly in urban areas. In fact, 92 per cent of women and girls in rural India (and 72 per cent of the overall female population) do not have access to any kind of mobile device. Furthermore, the overall smartphone penetration in India is no more than 350 million, and it is supposed to be one of the basic tools to get online and on social media. Even though India accounts for the highest number of Facebook users, paradoxically, a large section of India’s population is yet to get online. However, if we include WhatsApp, launched as a private messaging platform, as a legit social media tool, we will see considerable use of the internet for sharing information within social networks.

Having said that, social media is at best an urban adoption and can only give trends of activities related to urban populations. Election is a national phenomenon and rights-based activity where participation from rural India is not only higher in percentage but also in terms of ratio. In such a scenario, being dependent on social media to analyse election trends could lead to skewed results and, at best, armchair data journalism.

Indians will need to demand from public officials a strong data protection law

Apar Gupta

Apar Gupta

Lawyer and a volunteer trustee at the Internet Freedom Foundation

Let me start by asking you a question: Have you ever read the terms of service or the privacy policy of the several online service or smartphone applications that you frequently use? Chances are even if through some spurt of energy you started combing through their legalese, such initiative is dulled by their length and phrasing. Research has consistently demonstrated that these agreements are almost never read. For several online services today, one does not even need to scroll past such terms or click on any button to signify the agreement by a user.

This common practice in user behaviour demonstrates not only a failure of knowledge, but a mismatch between expectations, which are set between users of online services and the platforms who gather, analyse and process their personal data. Such expectation of responsibility, which comes with extending trust has been dented over the past few days with the growing Facebook and Cambridge Analytica data scandal.

Let me now start by clearly stating that there are no certain or complete answers to the problem of data protection or online privacy. This certainly does not include going to law school, gaining an expertise in contracts and negotiating an online agreement to post a picture on Instagram. This is a fantastic solution, and clearly most will agree the world is a better place with less lawyers arguing over indemnity clauses.

A large portion of the burden for privacy compliance has to shift from users to regulators. This becomes important given the terms of service or the privacy policies are crafted with intentional flexibility and power tilted towards online platforms. Much more is dependent on the practices of online companies than such agreements and if made in a clear comprehensive manner, they can be an important component in furthering consent, and by themselves are only a small part of a larger regulatory toolkit.

So, while many may be relieved on hearing that caring about their online data is not their problem, they do have their task cut out. India has seen indiscriminate use of personal data without a data protection law principally due to the desire to increase the enrollment and pervasiveness of Aadhaar. Many have argued that Indians do not care about their privacy or data protection, and the absence of such protections promotes innovation. A good starting point for those concerned by the Cambridge Analytica data scandal is to challenge these assumptions.

This is tough work. A present committee which has been constituted to formulate it has been criticised for being packed with pro-Aadhaar voices and lacking civil society or data protection experts. Going forward, people will need to organise and demand from public officials a strong data protection law — but also to challenge our own behaviour which has willingly accepted the gifts of digital surveillance.

To say that Facebook data can help ‘fix’ elections in India would be a stretch

Abhishek Krishnan

Abhishek Krishnan

Business Analyst, ThePrint

Big data is the nightmare that got too real too soon. Let’s be honest here. The influence wielded by big data analytics is symptomatic of a larger problem that has only recently come up for discussion in the mainstream, with the Facebook data leak scandal. Predictive/selective targeting has been the plank on which both Google and Facebook have virtually been building their advertising empire for a while now.

Simply put, big data in the hands of any individual/organisation, with the know-how to harness it, can influence not just electoral behavior, but human behaviour across spheres. The threat of echo chambers created by platforms like Facebook has suddenly turned real, with their destructive potential to threaten the vibrancy of a democracy by robbing voters of their mind’s sovereignty — which is already a lucrative playground for all the Facebooks and Amazons of the world.

Although big data holds the potential to swing election results by taking away the choice of content-viewing from the user and placing it with the platform owner, to say that it can ‘fix’ elections in the true sense of the word would be a stretch. It is the digital form of offline identity-based appeasement that has been a regular feature of Indian elections. It merely allows political parties to accentuate the same strategy by capitalising on readily available personal data, incessantly targeting the belief systems of a certain section of the electorate by reaffirming their biases.

The only cause for concern is the legality of it all. The lack of transparency in data-sourcing and the nascence of the political consulting space make it a grey area in terms of regulation. In India’s case, for example, it is only post-2014 that new avenues for electoral influence have opened up, owing to the strengthening of internet connectivity and the resultant growth of digital platforms. The regulatory/ legal uncertainty in this situation is a part of the larger ambiguity in data privacy in the online space.

We have only just scratched the surface with respect to the use of technology and data in the electoral sphere, which has been largely untouched by its influence. The electorate, however, has now turned into a customer segment that can be manipulated to act a certain way. But it will be a while before firms can take away all agency from the voter.

Compiled by Deeksha Bhardwaj, Journalist at ThePrint.

It is easy to fix Indian elections by 1. Lying and 2. Convincing perfectly well off Hindus that something is drastically wrong with them, and Muslims and lower castes are responsible for this imagined drastic wrong. Facebook lucked out by offering a silly forum for ppl to flaunt their holiday pics. Now Sherlocks of the world think they are these master puppeteers. It’s just a third rate dating site.

डिजिटल का जमाना है। डेटा प्रोसेसिंग और प्रोफाइलिंग को रोकना नामुमकिन है। बाज़ार तो हमेशा मौजूद है और उसमें अपनी दुकानदारी भी चमकानी है। दुकानदार को पता है की बिना ग्राहक को समझे सामान बेचने में पिछड़ा जा सकता हैं। इसलिए डिजिटल पर पड़े अथाह जानकारियों का इस्तेमाल क्यों न किया जाए ?जिन जानकारियों को हासिल करने के लिए किसी कंपनी में मार्केटिंग डिपार्टमेंट होता है,वह जानकारियां अगर थोक के भाव में आसानी से मिल जा रही है तो इसमें परेशानी क्या है ?

अगर मानव सभ्यता अभी तक आसानी से बाजर के कुकर्मों को सफलता का मानक मानकर अब तक पचाती आ रही है तो डेटा प्रोफाइलिंग को भी आसानी से पचा लेगी । अभी तो रोबोटिक्स और आर्टीफिशियल इंटेलिजेंस का बम फूटेगा। जिसका पूरा कारोबार ही डेटा प्रोसेसिंग और प्रोफाइलिंग पर चलता है । तब क्या होगा ? कुछ नहीं । बस हो हल्ला। या तो पूरी दुनिया का विकास का मॉडल बदल दीजिये या डाटा प्रोसेसिंग और प्रोफाइलिंग को विकास की जरूरत बनाकर स्वीकार कर लीजिये। बाकि सब तो चलता रहता है ।