PastForward is a deep research offering from ThePrint on issues from India’s modern history that continue to guide the present and determine the future. As William Faulkner famously said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Indians are now hungrier and curiouser to know what brought us to key issues of the day. Here is the link to the previous editions of PastForward on 1962 India-China war, Jammu & Kashmir accession and Pokhran nuclear tests. For now, this is available immediately to all ThePrint readers.

Very soon PastForward will be among the premium offerings that go behind a paywall, only available to subscribers. As will Chinascope.

If you score 80/100, you’ll get an A. If you score 90/100, you’ll get an A+. If you score 11/22, you get an OBC.

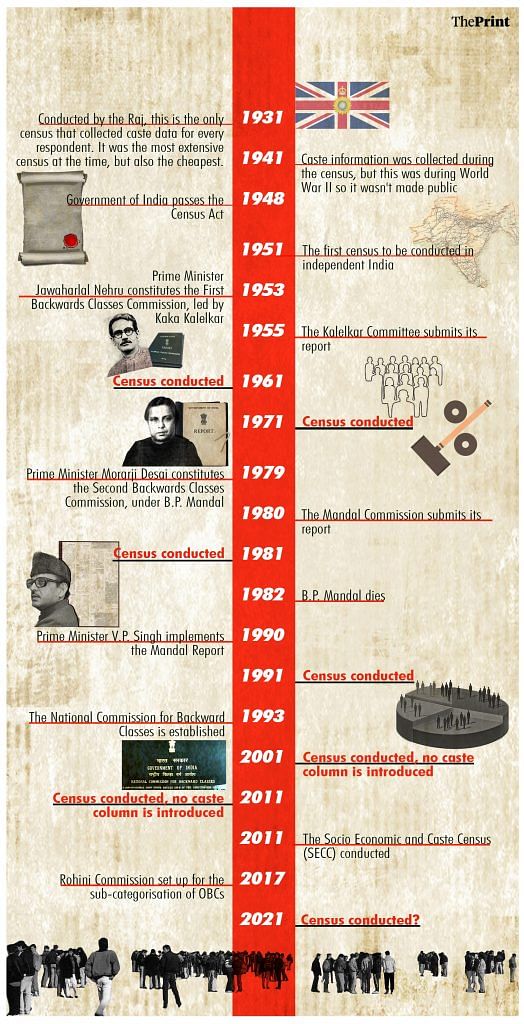

This was how Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in India were classified in 1979 in the Mandal Commission Report. The report itself borrowed heavily from the questionable British colonial census in 1931. From 1931 to 2021, it’s been 90 years of heady and polarising politics over counting how many Indians are OBCs, and more importantly, who is an OBC.

Seven states are heading to the polls next year in 2022, and the demand for a caste-based census is back in the public eye. Several political parties have called for an OBC census, marking it as an important electoral issue. The demand is especially significant in the state of Uttar Pradesh, where OBCs and Scheduled Castes make up 60-70 per cent of the population but still face inequalities.

1979 was the last time there was a national attempt to identify and list OBC communities under the Morarji Desai government and evaluate them against social, educational and economic indicators using this point system. All castes with a score above 50 per cent —that is, 11 points — were listed as socially and educationally backward, and the rest were “advanced” communities.

Rajiv Gandhi had famously called the Mandal Commission Report a “can of worms,” and told his aides he wouldn’t go anywhere near it. But ironically, he “thumped” the table from the opposition benches when Prime Minister V.P. Singh introduced it in Parliament.

What’s curious is this OBC “can of worms” has been opened at least five times — and almost immediately shut every single time. One was 90 years ago, another was highly flawed, one commission changed its mind, another commission led to riots, and yet another keeps requesting extensions.

This is what makes the current debate around the OBC census so complex, and a historical understanding so important. The census is a must before you ask any question on reservation, the ‘creamy layer’, and caste privilege in India.

Also read: Real reason no govt wants OBC count in Census – it will reveal inconvenient truths

Kalelkar to Mandal – one step forward, one step backward

In the beginning, there was ‘commission’ pe ‘commission’.

Jawaharlal Nehru constituted the First Backwards Classes Commission and appointed Kaka Kalelkar to head the commission, who seemed doubtful about the mission from the start. The commission was a definitive move to treat backward classes as separate from SCs and STs, and it submitted its report in 1955.

But Kalelkar was closer to M.K. Gandhi than B.R. Ambedkar in his thinking on caste.

As he wrote in his report, he “was not blind to the good intentions and wisdom of our ancestors, who built the caste structure.” He was a man deeply committed to the Gandhian idea of a united India that was above caste discrimination. Kalelkar had been a freedom fighter, and was personally tasked by Gandhi to popularise Hindi as the national language of India. Kalelkar was from Maharashtra, but was so close to Gandhi and such an integral part of the Sabarmati Ashram that Gandhi reportedly called him “Savai Gujarati,” which translates to a quarter more than a Gujarati.

Kalelkar wrote in his report that prejudice doesn’t hold a community back educationally or economically. “If backward communities have neglected education, it is because they had no use for it. Now they have discovered their mistake. It is for them to make necessary efforts for their prosperity. They will naturally receive whatever help is available to all citizens,” he concluded. Continuing in the same vein, he also wrote that backward classes should remember that any liberal policies they find in the Constitution are a result of “the awakened conscience of the upper classes themselves.”

Ultimately, Kalelkar himself began to doubt his work and methodology, and suggested that the report and its recommendations be rejected.

In a letter in the report, he wrote, “I am definitely against Reservation in Government services for any community for the simple reason that services are not meant for the servants, but they are meant for the service of society as a whole.”

Then came B.P. Mandal, who could not have been more different from Kalelkar.

The incendiary Second Backward Classes Commission was appointed by the Janata Party in 1979. Mandal was more resolved than Kalelkar to work past caste-based exclusion – he believed that social backwardness was the direct consequence of caste status, and used systematic survey methods to conduct his research. Mandal put together the point system to evaluate backwardness, and used data from the 1931 Census to report that these backward communities constituted about 52 per cent of India’s total population.

Mandal was the right person for the job the second time around.

Mandal was the son of social reformer, scholar and freedom fighter Ras Bihari Lal Mandal. Politically and socially aware from a very young age, B.P. Mandal became an elected official at the young age of 23. He went on to become one of the first chief ministers in India from a backward class when he was elected chief minister of Bihar in 1968. It’s a different story that he resigned after little over a month.

During his tenure as chief minister, part of the Ganges river caught fire due to an oil leak. Dominant caste MLA Vivekanand Jha said, “If a shudra becomes chief minister, it is bound for the water to catch fire”. Mandal replied, “The fire in Ganga has been caused due to an oil leakage, but the fire in your heart which has been caught due to a son from the Backward community becoming the Chief Minister; can be felt by all.” Casteist slurs are banned in Bihar’s assembly because of Mandal. One politician used the word “gwala” (dairy farmer) in a derogatory manner and didn’t apologise because the word was a natural part of his vocabulary — Mandal retorted by saying swear words were also part of his vocabulary. A notice was then issued condemning use of the word as unparliamentary.

He also made headlines when he ‘humiliated’ his ruling party, Congress, by joining the opposition in the state assembly to demand justice for people who had suffered caste atrocities. Mandal was elected to the Lok Sabha for the third time in 1977, and was asked to form his commission two years later.

Mandal knew his report and its recommendations would be hard to swallow.

“It is certainly true that reservation for OBCs will cause a lot of heart burning to others,” he wrote in the report, which he submitted in 1980 to a government that was now led by Indira Gandhi. The Janata Party had been voted out by then. The report — and its fiery content – then spent a cool 10 years in the government’s deep freezer. Mandal died in 1982 and never got the chance to defend and explain his report in Parliament. It was tabled, debated, and then dismissed by the Congress in 1982 and 1983. It lay forgotten after that.

But Mandal’s report got a glorious afterlife. Click on any article on caste or the debate around the OBC census and you’ll find its mention.

Prime Minister V.P. Singh introduced the report on 7 August 1990 as part of his commitment to social reform during Ambedkar’s centenary year, which he designated as the “year of social justice.” However, he was reportedly convinced that implementing the report would checkmate his political rival — his former deputy prime minister Devi Lal who had left his post on 31 July.

“I know when we try changing the structures, there will be resistance,” he said in the Rajya Sabha on 9 August. Opposition leader Rajiv Gandhi called Singh the most divisive man after Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Mayawati criticised the report’s hasty implementation.

The decision triggered the “Mandal-Mandir” chain of events. Widespread protests broke out, Delhi University student Rajeev Goswami self-immolated to protest its implementation, and the fragile V.P. Singh government fell apart. Cities shut down across the country as protests led to burnt government buildings, suicide attempts, and disruption of road and rail traffic. In Lucknow, dominant caste medical students protested by polishing shoes in an attempt to demonstrate their ‘fate’ if reservations were implemented.

Even the media was divided: Video magazine Newstrack was openly anti-Mandal, and journalist Madhu Trehan said “V.P. Singh has the blood of students on his hands.” The Indian Express ran editorials urging dominant castes students to continue protesting. India Today ran an anti-reservation cartoon — V.P. Singh stood grinning with marginalised communities on a ship while dominant caste students drowned holding their merit certificates — and also published an opinion denouncing Rajiv Gandhi’s “cynical waffling.”

To try and shift the political debate, the BJP began to press the demand for a Ram Mandir in Ayodhya and L.K. Advani embarked on his rath yatra on 25 September 1990. When Advani was arrested in Bihar, the BJP withdrew support from the government and V.P. Singh resigned — exactly three months after he implemented the Mandal Commission Report on 7 November 1990.

Also read: On EWS quota, Modi govt just using Congress’ bad idea and Sinho Commission report

More attempts and secret OBC numbers

In the aftermath of the Mandal fire, several attempts have been made to enumerate castes — but none of them has been successful.

Based on Mandal’s estimation of 52 per cent of the population being OBC, 27 per cent of public sector jobs and education seats was reserved for the OBCs. But without data, we don’t know if this number is justified.

The only way to have consolidated, updated, and accurate data on the vast OBC population in India is to reintroduce the caste question in the census.

A National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC) was set up in 1993 as an outcome of the Indra Sawhney judgment, and became a constitutional body under the 102nd Constitution Amendment in 2018. The NCBC was given the responsibility to investigate complaints and grievances and examine welfare measures for backward classes, and it maintains a central list of OBCs. It doesn’t, however, maintain population sizes.

The 2001 Census came and went, and a caste column was not introduced because of the violent backlash against the Mandal Commission.

The conversation came up again in 2010, in time for the 2011 Census, and the Manmohan Singh government decided to have a caste column in census forms. All parties agreed to the need for a census, but then-Home Minister P. Chidambaram decided against it. Instead, the government commissioned a separate Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC), which took five years to complete and was submitted to the Narendra Modi government in 2015.

The SECC’s preliminary data, on submission, was reportedly highly flawed — and it has never been made public. The expert group appointed to look into the report never met, and its chairman Arvind Panagariya left the country to accept a professorial role in an Ivy League institution. The Modi government’s latest attempt to enumerate and categorise OBCs is the Rohini Commission. Set up in 2017, the commission is trying to look at the equitable redistribution of the 27 per cent quota reserved for OBCs. It was originally supposed to submit its report by March 2018, but is on its eleventh extension.

“Dominant groups in government bureaucracy don’t want these numbers to be in the public eye, because then they will have to start giving up their seats,” said G. Karunanidhy, general secretary of the All India OBC Federation.

But former Census commissioner, M. Vijayanunni, told ThePrint that anything about the OBC census is a purely political decision.

The Raj’s cheapest census

Whether we’ll see any new numbers or not, remember the Census also has a reputation for being flawed. And it has a lot to do with its roots. Even now, most of India’s caste calculations and categories are based on a survey done by the British almost a century ago, on a budget. And that’s saying something.

The 1931 Census was the most extensive census done at the time, but it was also the cheapest: The 1921 census in England and Wales cost $45 per 1,000 people, while the 1931 Indian census cost $5 per 1,000 people.

Experts like anthropologists Arjun Appadurai, Nicholas Dirks, and Bernard Cohn have criticised the colonial census for actively creating social categories that set a hierarchy in stone through laws and rituals that the British administration introduced. In fact, according to Cohn, most writings on caste between 1880 and 1950 have been done by people involved in the census of India.

The British struggled with how to conduct the census. In fact, when presenting the first decennial census to British parliament, the colonial census operations described their own methodology as “not satisfactory” due to “intrinsic difficulties,” because of which only “a few particulars” were collected.

The British government had been collecting demographic information for over 10 years before they held the first synchronous census of India in 1881. They were not sure of how to classify communities according to their caste: A memorandum submitted to the British parliament on the 1881 census admitted that the process was “not satisfactory, partly to the absence of a uniform plan of classification, each writer adopting that which seemed to him best suited for the purpose.”

They puzzled over conducting a census for such a diverse population so much that W. C. Plowden, who was the census commissioner in 1881, recommended that every province in India should have an officer with “a taste for, and a knowledge for, archaeological research.” He hoped that this would make it easier for subsequent censuses. Plowden decided that castes would be grouped under new categories: Brahmins, Rajputs, and “other castes,” which included castes in good social position, oppressed castes, and ‘aboriginal’ castes.

Herbert Risley, the 1901 census commissioner, called the 1891 Census “a patchwork classification in which occupation predominates, varied here and there by considerations of caste, history, tradition, ethnical affinity, and geographical position.” The confused commissioner wrote about the difficulty of asking someone about their caste, because they might name anything like “an obscure caste… a sect… a sub-caste… an exogamous sept… a hypergamous group… may describe himself by… occupation or… the province or tract of country from which he comes.”

The British census commissioner in 1931, J.H. Hutton, wrote that the Indian people covered in the census “present every aspect from that of the latest phase of western civilisation to that of the most primitive tribes.” This was the last time there was a caste census, but it didn’t make a distinction between Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes, and it was voluntary for anyone who wasn’t “primitive.”

The 1931 Census also did not require an answer on caste identity from Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, and Brahmin Hindus. It was only recorded if the respondent gave an answer. Which is a problem in a country where most religions adhere to the caste system, not just Hindus.

Also read: A state survey is no solution to lack of political will for national caste census

No entry to states on census

So, is the onus on states or the Union to count the OBC population now?

At the dawn of Independence, India wanted to be a new, secular country that wished to say caste no bar. Thus was born a census approach that didn’t exactly match the British one or ground reality.

The colonial administration looked at caste enumeration as a way of codifying and categorising caste, and newly independent India was keen to be a representative and inclusive state that had moved beyond caste and religious differences. The result of these opposite approaches to the census is a highly skewed and incomplete picture that doesn’t match ground reality — but, unfortunately, it became the blueprint for future censuses, as well as public policy.

The Census Act of India was passed in 1948, under which the Union government had the sole responsibility of appointing a census commissioner and setting a date for the decennial census. The 1951 census, the first in independent India, was conducted with a steadfast belief in a modern, democratic country, and only collected caste data for the most downtrodden members of society, the Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

While state governments maintain state lists and records of OBC populations, they are not authorised to carry out a census and can only conduct surveys and set up commissions.

The Modi government too back-pedalled on its 2018 promise to conduct an OBC census. It’s a risk that no government wants to take anymore, despite promising it — Rajiv Gandhi’s ‘can of worms’ comment must be ringing in their ears too. Now the BJP government is trying to push the onus onto states.

Recently, when asked about why the government is reluctant to conduct a caste census, BJP OBC Morcha national president K. Laxman said states are free to conduct their own census and use that data.

Dilip Mandal, former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine and founder of Centre For Brahmin Studies, told ThePrint that only the census commissioner has the technical capability to conduct a census — the SECC was done by the Ministry of Rural Development and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation over five years, and is largely seen as a failed mission.

The only option for enumerating OBC lies in the hands of the Union government, which has termed the process “administratively difficult and cumbersome.”

K. Laxman told ThePrint that while the BJP is not opposed to a caste-based census, the party has not taken a decision on what to do yet — even though there is a demand for it. He said other parties and governments have also been unable to crack the issue. “We are not against a caste-based census, but it requires thorough research and study,” Laxman said. “The teething problems have to be solved.”

In July 2021, the Union Minister of State for Home Affairs Nityanand Rai said that the government has decided “as a matter of policy” not to enumerate castes other than the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in the census.

M. Vijayanunni, who served as the census commissioner from 1994 to 1999, wrote that there shouldn’t be any procedural difficulties in collecting caste data while conducting the census. While it might take longer to compile and analyse the data, the collection itself should not take extra effort.

Even the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has found a way out of the OBC census demand, by resorting to Ambedkar.

The former sarkaryavah of the RSS, Suresh Bhaiyaji Joshi, said in 2010 that the RSS was opposed to registering caste, because doing so would be against Ambedkar’s vision of a casteless society and would offend respondents and ruin social harmony. Vishnu Gupta, president of the Hindu Sena, told ThePrint that the government talks about caste only to play vote-bank politics, and that a caste-based census would divide Hindus. “This should not happen in India,” he said. “It would only increase caste-based prejudice.”

The battle for backwardness and ‘oppression Olympics’

Now every other community wants to be OBC – Jats to Marathas to Lingayats – and get the benefits of reservation. But what number will India base that selection on? Certainly, not the 1931 census.

Since we don’t have an exact count of the different castes and communities swept under the umbrella term “Other Backward Classes,” some upwardly mobile groups are dominating the system while others are left scrambling for breadcrumbs.

A lack of clarity has led to an unequal structure. What complicates things even further is that states maintain different lists of OBCs, and some communities end up getting caught in the crosshairs.

The Union government gave the states the liberty to choose their own criteria to define backwardness in 1961 and create their own OBC lists. After this, several state governments set up commissions and began to set aside reserved categories in jobs and educational institutions, and have successfully been able to revise and update their lists of backward classes.

In the case of some south Indian states, the movement for affirmative action has a history that predates independent India. Tamil Nadu, for example, has had caste-based reservations since 1921 — and today has a reservation quota of 69 per cent while other states are trying to maintain the 50 per cent. Kerala extended reservations to caste groups like the Ezhavas and religious minorities in 1936, and also enumerated backward classes — in 1968, the Communist government under E.M.S. Namboodiripad conducted a comprehensive socio-economic survey of the various castes present in Kerala.

The states present their own anomalies. Jats, for example, are listed as OBCs in Delhi, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, while in other states like Haryana, they are vying for OBC status. In 2015, the Supreme Court struck down the year-old move to include Jats in the central OBC list.

Then there is the Maratha reservation issue.

The community, whose members once ruled over the Maratha empire, have been demanding reservations — even though they have significant political influence in the state, they lack access to resources and largely work in agriculture of the informal economy.

The Supreme Court also struck down special status for the Marathas, a dominant community in Maharashtra, in May 2021.

Without an official enumeration of castes across India, it’s impossible to know whether the demands of communities like the Jats, Marathas, Gujjars, and Lingayats are valid or not.

“Whichever community wants to demand a different status should be allowed to — they have a right to demand. But we need to know if their demand is justifiable, and that’s why we need numbers,” said G. Karunanidhy, General Secretary of the All India OBC Federation.

The NCBC has a questionnaire, available on their website, which allows respondents to either request for their community to be included in the central list of OBCs, or complain about over-inclusion in the central list.

Migration is yet another layer in this complicated negotiation for OBC identity. The NCBC says that if an OBC person migrates to a state where they are not listed as an OBC, they are not eligible for OBC benefits there.

OBCs outside Hinduism

Some states have separate reservations for religious minorities and non-Hindu OBCs. However, the same issue arises: Certain caste groups end up cornering reservations.

Faiyaz Ahmad Fyzie, a Pasmanda social activist, told ThePrint, “There is no denying that a caste column should be drawn in the census. While there is a headcount of SCs and STs, OBCs have generally been left out. For Muslims, there is an absence of counting for all three categories. Pasmanda movement is demanding the counting of OBCs, as well as SCs and STs in the census for all Muslims.”

Fyzie added that dominant caste Muslims — the Ashraafs — are silent on the issue of the caste census.

There are also alliances being built across religious lines. Dalit Christians and Dalit Muslims have been campaigning together to be added to the SC list at the central level.

Also read: The debate on caste census has forgotten Pasmanda Muslims again

India isn’t the outlier, at least it tries

India clearly struggles with enumerating different demographic groups, but at least it tries — a surprisingly high number of countries have made it illegal to collect data on race and ethnic origins.

In India’s case, the approach is further complicated by the caste system.

“No other country has a ‘caste-based’ headcount or such a plethora of castes and maze of caste-based reservations and quotas as in this country,” said M. Vijayanunni, pointing to the difficulty of tackling identity groups within the census.

Most Western countries don’t collect racial and ethnic data, and the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada are actually outliers. In the US, “white” appears as a single race category, much like how the ‘general’ category is a single option in India. However, the American census also asks the respondent to write their origin along with selecting “white,” allowing the respondent to disclose Polish, or German, or Irish heritage. Other races have clearly stated sub-categories owing to the country’s diverse immigrant and indigenous population. The United Kingdom also asks for uniform information on ethnic origin in its census, with broad categories of white, mixed, Asian, and black.

Caste by numbers

Whenever you talk about caste census, many Indians say, don’t do it. They say it will increase the divide between castes. But denying the problem won’t fix it either.

Castelessness, according to sociologist Satish Deshpande, is the phenomenon that makes caste invisible for the dominant castes and hypervisible for non-dominant castes. Hence some want dominant ‘general’ caste categories to be counted too.

For India to overcome the chasms caused by caste and fix affirmative action, we need numbers. And recent ones.

Speaking to ThePrint, OBC activist and chief of the Mandal Army, Anirudh Singh Vidrohi, said that a census is not just necessary for OBC castes, but for all castes.

“All castes, whether backward castes or upper castes, must be counted in the census. This information will be the basis for understanding who is getting and not getting the benefits promised to them,” he said.

With inputs from Humra Laeeq and Krishangi Dahiya.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)