During these months, the level of riots and killings and mass flight intensified. The events had little pattern except on a very local scale of attack and then retribution, escalating into wider areas, subsiding for a bit, and then occurring again not far away, either from a new provocation or a delayed further retribution for an earlier attack. The police were outnumbered and increasingly perceived as unreliable because of their communal affiliations. The military, not yet transitioned into separate Indian and Pakistan armies, attempted to exert control as best they could. Despite suggestions from London and Mountbatten’s staff that provincial and district authorities be given permission to shoot to kill, or that martial law be declared, there was marked hesitancy to do so for the fear of inflaming tempers further and decisions were not made until last week of May 1947 as is evident in the Viceroy’s Report to the Secretary of State of India:

“I asked if the Cabinet would support me to the hilt in putting down the first signs of communal war with overwhelming force, and if they agreed that we should also bomb and machine gun them from the air, and thus prove conclusively that communal war was not going to pay. This proposed policy was acclaimed with real enthusiasm by the Congress and Muslim League members alike, and when I looked across at the Defence Member, Baldev Singh, and said, “Are you with me in this policy,’ he replied Most emphatically ‘Yes.’”

The net result, however, was relatively uncontained escalation of terrible attacks on ordinary people who tried to flee out of the cities to the countryside, or vice versa. As weeks moved on, increasing numbers of people tried to escape campaigns of pillage and killing by fleeing to presumed loci of safety in West Punjab (Lahore) or to Amritsar or another town considered likely to be assigned to East Punjab. The ambiguity and uncertainty contributed to the fear and the frenzy.

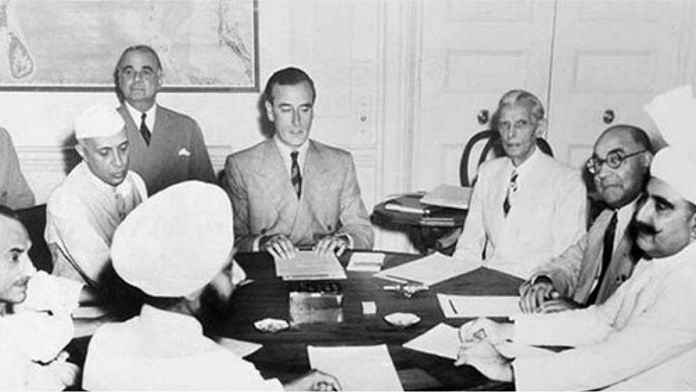

A most rapid series of events and decisions transpired in May and June, all leading directly to the acceleration of processes towards the partition of British India. During spring 1947, as communal tensions rose and the central government became increasingly divided between the Muslim League and the Congress, Lord Mountbatten moved to propose that the country be partitioned into two dominions, to be known as Pakistan and India. After both the League and Congress agreed to this plan “behind the scenes,” the British government announced its approval and Nehru, Jinnah, and Baldev Singh publicly accepted it on June 3, 1947. In a widely covered press conference the next day, Mountbatten referred to these two momentous developments: the agreement on the formal political structure for Partition and the accelerated timeframe in which to achieve it. The new date was August 15, 1947.

On Wednesday, June 25, 1947, the Viceroy assembled a meeting of the Indian Cabinet dedicated to the topic of “Refugee Problem.” The Minister for External Affairs and Commonwealth Relations opened the meeting by announcing:

“. . . that the problem of refugees had now assumed grave proportions and was particularly acute in Delhi where it was estimated that there were no fewer than 70,000 refugees; the United Provinces and neighbouring states had also to cope with large numbers of refugees.”

It was proposed in this meeting that a “Special Officer with appropriate staff” be appointed under the Home Department to set up an organization to manage refugee relief and analyze the problems and needs of “refugees from communal violence, whether from the NWFP, and the Punjab, or from Bengal and Bihar.” As far as can be ascertained, the Home Department did not take up this assignment and this immense task was not addressed until September 1947, when the new Pakistani and Indian governments were forced to face the debacle in their own ways.

Also read: ‘Not all inheritances from Partition are traumatic.’ Some stories are ‘celebrations’ too

In mid-June, the focus moved specifically to the highly volatile Punjab, where the boundary division for the creation of two new nations (India and Pakistan) would clearly also be the line of division of Punjab (and Bengal). Two joint arrangements were set up to manage the creation of transition principles for the machinery of government (Joint Evacuation Plan) and for the military protection of populations (Military Evacuation Organization, MEO) who might be expected to move. Neither Lord Mountbatten queried in his press conference on June 4 regarding the possibility of large-scale transfers of populations nor Mr V.P. Menon, the senior Indian civil service officer who served as a constitutional advisor to Mountbatten, considered the possibility of large-scale transfers of population to be likely.

The Punjab Partition Committee, a joint Indian and Pakistani group of politicians and technicians, was set up by Governor-General Jenkins on June 16, 1947, in close consultation with Mountbatten and others. Continuing its work (re-named Partition Council on June 26, 1947), its remit was to advise on a number of key issues that would best be settled before mid-August, among them were the division of finances, the division of the police, and the division of the senior administrative services along with their office equipment. Important progress was made but time ran out. Yet this committee continued to have sway as a respected bipartisan deliberative body until early September 1947, when both countries had established their Emergency Committees of the Cabinet (ECCs).

The Punjab Boundary Force, developed in June and in operation on July 1, 1947, had 10-15 battalions each from India and from Pakistan. The units were merged to provide communal diversity and set up to provide security for refugees and townspeople along both sides of the Punjab border. By August 31, it was disbanded, overwhelmed by the large numbers of people fleeing in distress, and evidently having difficulty with command, given the communal affiliations of the troops. Its difficulties could be taken as a late warning sign of how incendiary the months ahead might be.

The third and most portentous of the ad hoc arrangements developed in this transition was the Punjab Boundary Commission. A British lawyer, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, arrived on July 8, 1947, and was put to work in an office in the Viceroy’s quarters, instructed to define and draw the lines that would divide British India and define the boundaries of an India independent from the British rule and a new nation, Pakistan. He relied on two commissioners (one for the Punjab and one for Bengal) and retained the power to resolve decisions, although he had never been to India and was not permitted to travel to see the country. In relative isolation, he had to determine, in six weeks, the political and human fate of over 300 million people whose ancestors had inhabited the subcontinent for millennia.

This excerpt from ‘The 1947 Partition of British India’, edited by Jennifer Leaning and Shubhangi Bhadada, has been published with permission from SAGE publications.

This excerpt from ‘The 1947 Partition of British India’, edited by Jennifer Leaning and Shubhangi Bhadada, has been published with permission from SAGE publications.