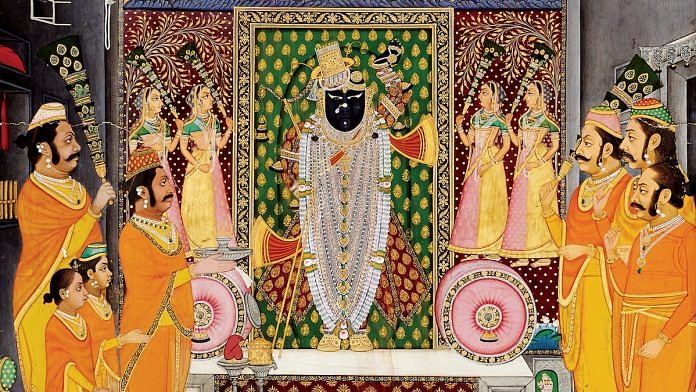

Tucked into the folds of the Aravalli Hills, about thirty miles north-east of Udaipur, is the bustling pilgrimage centre of Nathdwara, home to Shrinathji, the living image (svarup) of Krishna raising Mount Govardhan. The establishment of the deity’s haveli (mansion/temple), in Mewar in the seventeenth century, gave rise to a town that completely revolved around Shrinathji and the activities at his palatial shrine. The haveli brought together a myriad of diverse social groups such as masons, potters, tailors, silversmiths, embroiderers, brocade weavers, enamel (meenakari) workers, cooks and carpenters, all performing divine service (seva) for the child-god Krishna. Most importantly it fostered the growth of a painting community, drawn from various towns in Rajasthan, that came to serve the needs of the haveli and the pilgrims.

Nathdwara became a unique centre, its rituals and traditions remaining virtually unchanged for over 300 years. Until recently it was in a time capsule, maintaining artistic traditions that had vanished from the Rajput courts. It was the archive for the styles and techniques of the courtly painting studios of Rajasthan as well as the home to its own unbroken artistic tradition for over three centuries.

By the early eighteenth century, eight of the nav nidhi (nine treasures) had found refuge in Rajasthan, a land rich in artistic traditions and courtly styles of painting . Shrinathji, Navnitpriyaji, Vitthalnathji and Dwarkadhishji sought asylum in Mewar. Gokulnathji, Gokulchandramji and Madanmohanji made their way to Jaipur. Mathureshji was harboured first in Bundi but later transferred to Kota. Only Balakrishnaji went outside of the region, to Surat. The new pilgrimage centre of Nathdwara, established in 1671 as home to Shrinathji, was the fulcrum of these religious houses but also was conveniently located amid the painting centres of Kota, Udaipur and Devgarh and not too far from Kishangarh, Jaipur and Jodhpur.

Also read: How love, war and Mughal fine art inspired Kangra painting

Most of the royalty in these princely courts were followers of Pushtimarg prior to the dispersal of the svarups from Braj. Foremost was Maharana Raj Singh of Mewar, who invited Shrinathji to his realm. Kishangarh’s ruling clan had been disciples of the sect since Kishan Singh (r.1609–1615) founded the dynasty. Gopinathji, great grandson of Vallabhacharya, bestowed upon Maharaja Rup Singh (r.1643–1658) the image of Kalyanraiji. It would become the tutelary deity of Kishangarh.

Once the Vallabha Sampraday was established in Rajasthan, its princes realised that being associated with Shrinathji helped legitimise their regime, as if they were part of a powerful network. Maharao Bhim Singh (r.1707–1720) was formally initiated into the sect in 1719 and received the golden image of Brijnathji that became the tutelary deity of Kota. Almost a hundred years later Maharao Kishor Singh II (r.1819–1827) received Brijrajji, his private svarup, upon his initiation into the Vallabhacharya Sampraday. Even Zalim Singh, the crafty Kota minister who, by siding with the British, stripped Maharao Umed Singh (r.1771–1819) and his successor Maharao Kishor Singh of any real power, understood the need to pay homage to Nathdwara and the Vallabhacharya Sampraday to bolster his claim to the throne. The Vallabhacharya Sampraday was an influential presence in Rajasthan.

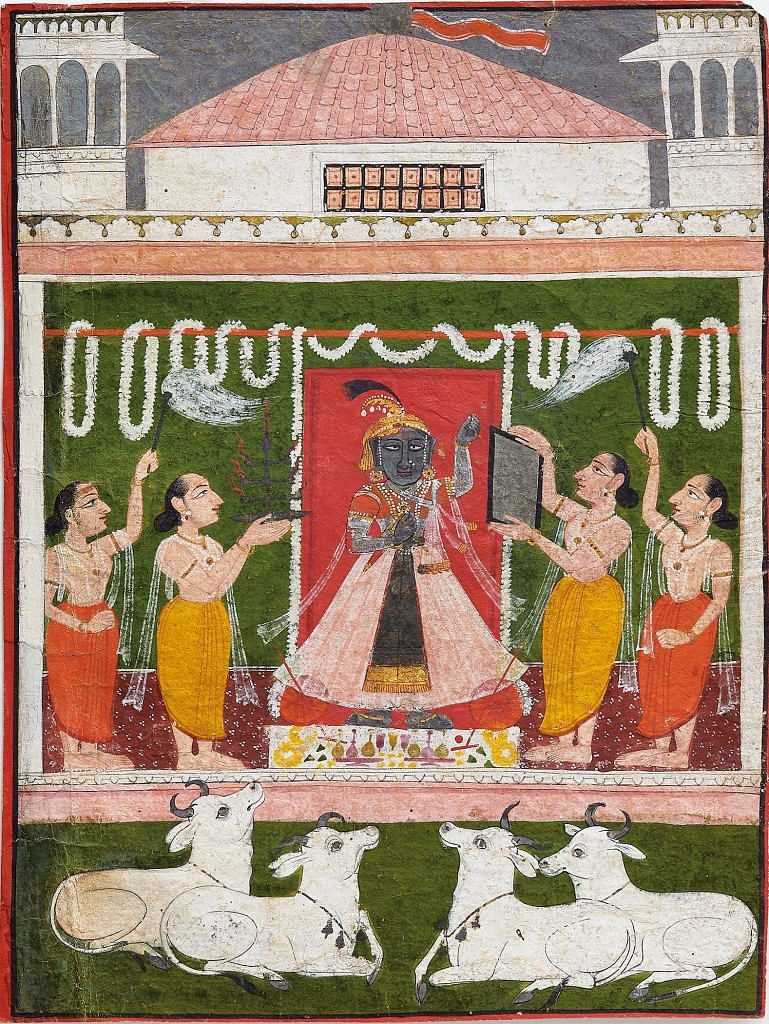

With all this piety and devotional activity surrounding Nathdwara, one would expect evidence of an artistic community serving Shrinathji’s haveli and its pilgrimage trade during the eighteenth century. Painting had played an integral part in the seva during Vitthalnathji’s time. Now the Vallabhacharya Sampraday was interacting with courts that boasted flourishing royal ateliers, yet nothing from Nathdwara is dated before the 1831 and 1834 paintings in Amit Ambalal’s collection. Paintings like the early eighteenth-century Mewar Dashahara (see CAT 73) attest to Shrinathji’s presence in Rajasthan, but do not foreshadow the colourful folkish style of Amit Ambalal’s early nineteenth-century paintings.

A series of Shrinathji shrine scenes in Amit Ambalal’s collection are so similar to each other that they must be part of a set. He dates them to the middle of the eighteenth century without mentioning provenance, although the placement in his text suggests that they are of Nathdwara origin. The figures are stocky, with round heads, fleshy jowls and heavy- lidded eyes. Although most of the goswamis are dhoti clad, some of the figures wear a gherdar vaga that is gathered at the waist and falls in pleats. In a couple of the paintings their uparnas (scarves) are draped over their robes like a monk’s hood. This manner of dress appears in no other painting from Nathdwara. That the men’s physiognomy somewhat resembles portraits from eighteenth-century Kota should not surprise us, since we know that the Kota rulers were ardent supporters of Pushtimarg.

Likewise, Ambalal’s paintings share facial features and body corpulence with Relia’s Manorath at the Dwarkadhishji shrine (see CAT 74). We have dated this work to ca. 1790 based on identification of the figures in the painting as the goswami brothers Vitthalnathji and Gokulnathji of Kankroli. We have further established that the Ambalal and Relia paintings are Kota or Kota-inspired. The question is whether this similarity is enough to pinpoint the style of these works as eighteenth-century Nathdwara. The time period must have been formative for the somewhat folkish nineteenth-century Nathdwara manner, but we do not have sufficient proof to identify its origin in the paintings under discussion.

Also read: How the golden era of Kathak began during the Mughal rule under Akbar

In her studies in Nathdwara in the 1990s, Tryna Lyons found no reference to artists who claimed to have emigrated from Kota to the pilgrimage town. In 1992, Lyons spoke with Kota artist Ramgopal Joshi (b. ca. 1937), brother of Omkarlal (20–25 years older) whom Kalyan Krishna had interviewed in the early seventies. Ramgopal confirmed what Omkarlal had said about their great-great grandfather Rupraj Hansraj, who was called from Nathdwara by the Kota ruler to paint shikars (hunting scenes). The transplanted artist became a painting ustad (master painter) in his new home. This narrative suggests that the school in Nathdwara was developed well enough in the late eighteenth century to produce artists who would attract the attention of outside patrons, but we are no closer to knowing what they were painting .

We do know that Kota royalty were Pushtimargis and paid homage to Shrinathji. The early nineteenth century saw many interactions between Nathdwara and Kota, reflecting a close relationship. Kota was home to the svarup Vitthalnathji from 1802–1822 during the Maratha disturbances. Kota’s Maharao Kishor Singh sought refuge in Nathdwara from the British protectorate in late 1821. Dauji’s successful intervention is commemorated on the walls of the Bada Mahal in Kota, where Dauji is depicted riding a richly caparisoned elephant, attended by Maharao Kishor Singh. Then in ca. 1825 Dauji and Maharao Kishor Singh participated in a liturgical ceremony for Brijnathji at Kota which is recorded in a painting. All this interaction in the nineteenth century led to paintings like CAT 75 in Relia’s collection.

This brings us back to the question of what was being produced in Nathdwara’s artistic community in the eighteenth century. We simply can’t be sure. The Ambalal paintings appear to be Kota, not the forerunners of the brightly coloured folkish style that appears on the scene as a fully developed genre in the nineteenth century.

The Nathdwara style is an amalgam of the different painting styles of Rajasthan. As consummate copyists, the artists even appropriated stylistic features from Deccani paintings. Although we can identify some of the influences like the Kishangarh elements in the ‘Assembly of Goswamis’ we are still struggling to make sense of the development of style.

Even discovering the artists’ places of origin has not been helpful because once they had shifted to Nathdwara they followed the prevailing manner, producing whatever pilgrims and patrons demanded. There are two main subcastes of artists in Nathdwara, the Adi Gaurs and the Jangirs. Although the Adi Gaurs claim to have come with Shrinathji when the svarup was spirited away from Braj in 1669, their strongest argument for being early arrivals in Nathdwara is their proximity to Shrinathji’s haveli. They live in the Chiteron ki Gali located directly behind the temple. The Jangirs who seem to have trickled into Nathdwara from different parts of Rajasthan over the last two hundred years live in the Nai Haveli, an area some distance from the temple.

This excerpt from ‘Nathdwara Paintings from the Anil Relia Collection: The Portal to Shrinathji’ by Kalyan Krishna and Kay Talwar has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

This excerpt from ‘Nathdwara Paintings from the Anil Relia Collection: The Portal to Shrinathji’ by Kalyan Krishna and Kay Talwar has been published with permission from Niyogi Books.

They are traitors… DON’T SUPPORT DEM AND GIVE MONEY.

PLAYING POLITICS BY THESE KIND OF ARTICLES.

TRAITORS!!!

JUST TO GET MONEY .POSTING THESE ARTICLES!