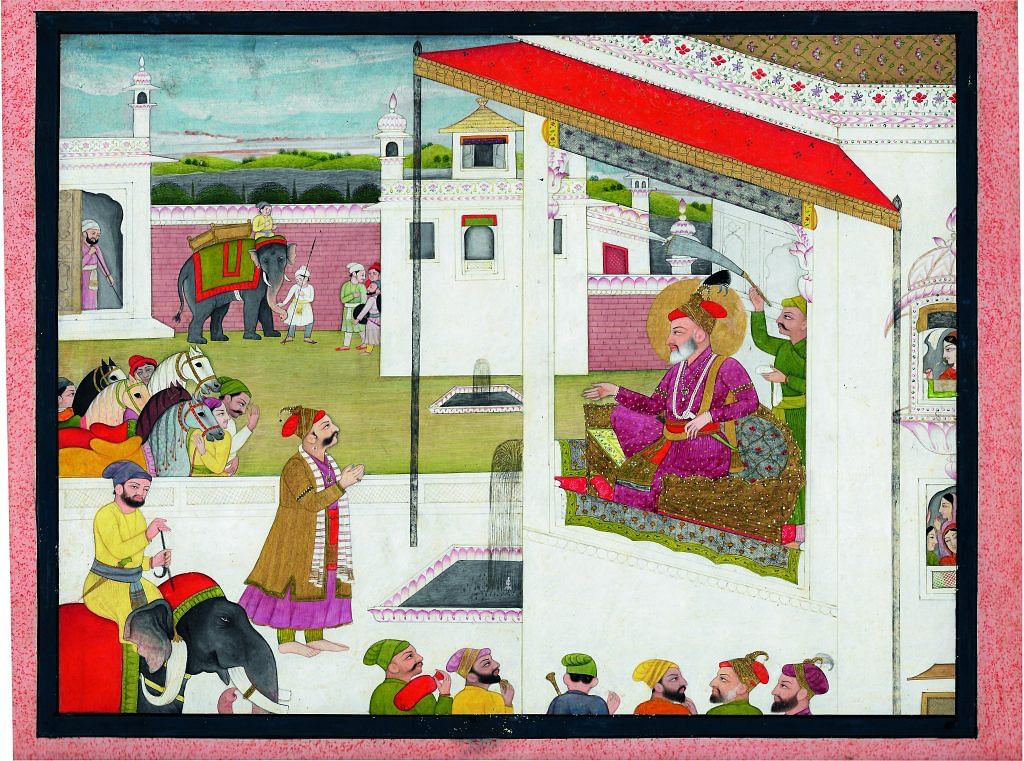

The art of painting reached new heights under the art-loving Akbar and his successors. New subject matter and techniques were incorporated in painting by the Persian masters working under Mughal patronage in collaboration with Indian painters, producing a sublime style of pictorial art. It was in such harmonious conditions that Mughal painting strode forward. Its influence no more remained confined to Mughal workshops and reached the royal courts of Rajput rulers, who came to be inspired by their Mughal overlords and competed with them by extending lavish patronage to painters.

During the reign of Akbar, the fertile tracts of present-day Pathankot, then part of Nurpur state, as well as the area of Guler state bordering the plains, were annexed to the Mughal Empire. After the conquest, Akbar’s revenue minister Todarmal had sarcastically informed that he had ‘taken the flesh and had left the bare bones for the Pahari landlords’. To compensate for this, the rulers of Nurpur and Guler states were conferred the position of mansabdar by the Mughal emperor. Rajput warriors were held in high regard in the Mughal court and assigned prestigious ranks in military expeditions. The Pahari Rajput rulers were thus indebted to the Mughal rulers and, being mansabdars, used to frequent the Mughal court to pay tribute.

The rulers of Nurpur and Guler states were gallant warriors and led the Mughal army in many expeditions. Because of this close association, they were well versed with the trends of the Mughal court. Mughal culture sought reflection not only in their attire but also in the fine arts, lavish princely hobbies, and material luxuries. Consequently, the 17th to 19th centuries saw a great revolution in art and culture in the region. The pictorial art of this period, which evolved and flourished under the patronage of the princely hill states, occupies a place of pride in the art map of the world as ‘Pahari miniature painting’.

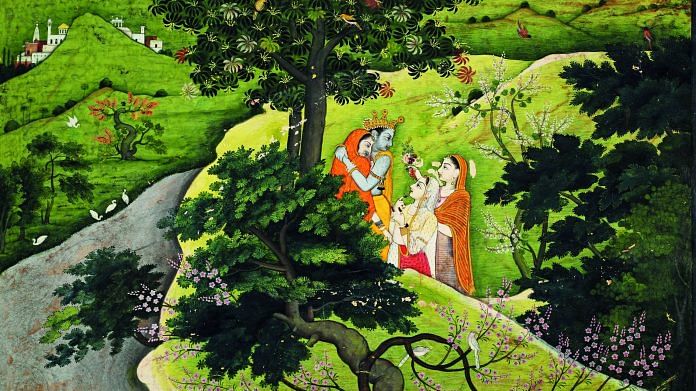

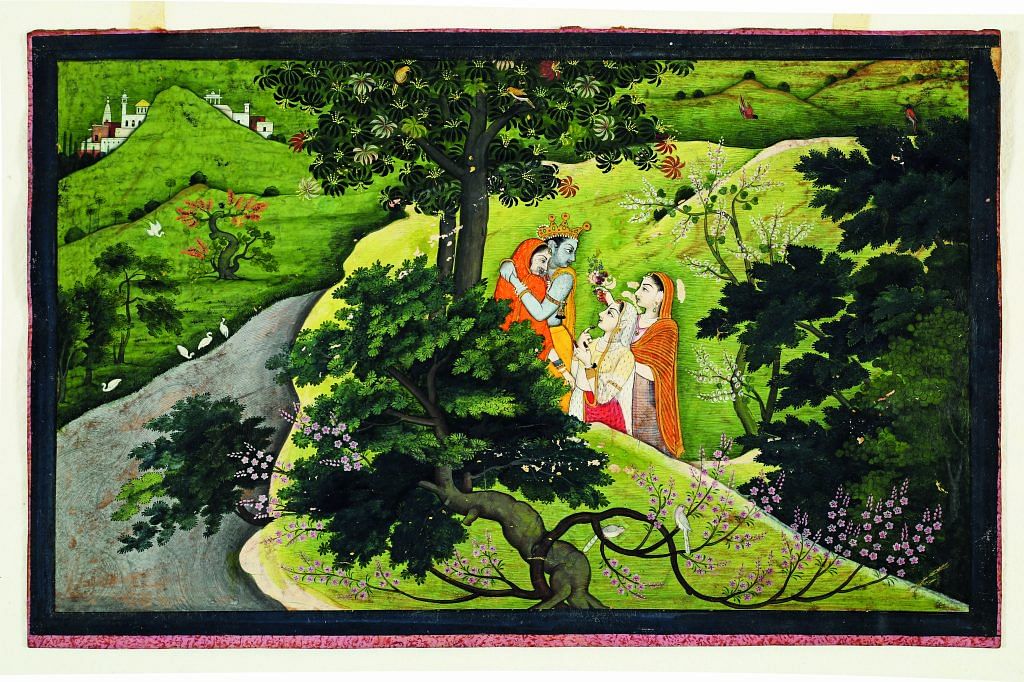

The hill region comprised many big and small princely states back then, and most of these states maintained ateliers. Pahari Rajput rulers had extraordinary love for art and used to embellish the temples, spacious mansions, and palaces in their principalities. They took into service the tarkhan-chitera (carpenter-painters), exhibiting a marked inclination towards fostering Pahari miniature painting. Perhaps the art of painting manifested the most beautiful medium of expression for their romantic passions and sexual impulses. Like medieval European knights, Rajput rulers, too, considered ‘love’ and ‘war’ as the great pursuits of life. Epic tales of their amorous dalliances and great conquests, as also legends of love, thus form the subject matter of Pahari painting.

Imbibing many of the finer aspects of Mughal painting, Pahari painting is characterised by rhythmic line drawings, the brilliance of colours, and minute decorative details. In the exposition of worldly as well as unworldly love, the painting tradition of Kangra valley is par excellence. Pahari painting, because of its unique qualities, occupies a place of pride in Indian art. The phrase ‘Kangra painting’ was first coined by John Lockwood Kipling, an art connoisseur and the first principal of the Mayo School of Art in Lahore. In an 1887 article, Kipling recounts the magnificence of ‘Kangra painting’ and chronicles its decline almost half a century ago:

The artistic industries of Kangra are now few and insignificant. Among native limners, Kangra ki qalm (the Kangra pencil) is a phrase occasionally heard and meant to distinguish the style or touch of a school of illumination and mythological picture painting that is supposed to have flourished there.

However, prior to this, the English traveller William Moorcroft had been a guest of Maharaja Sansar Chand of Kangra and had observed the latter’s earnest interest in painting. Unfortunately, Moorcroft lacked the requisite taste to appreciate this exquisite art form. Subsequently, it was Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy who brought to light the distinctive nature of Pahari painting. In 1910, he held the first-ever display of some of the finer specimens of Pahari painting at the All India Exhibition in Allahabad. In his book Indian Drawings,3 Coomaraswamy regards Kangra valley as an important centre of Indian painting:

The best characterised styles of Rajput painting are those of the Himalayan and Rajputana schools, which are, nevertheless, closely allied, and pass into each other almost imperceptibly. The Kangra valley paintings and drawings are the best defined and most characterised of the Himalayan schools, as well as the most abundantly represented. Allied work comes from Chamba and other Himalayan States.

Ananda Coomaraswamy was the first art historian to dazzle the Western world with his thought-provoking research and lectures on the philosophy of Indian art. He classified art from the hill states as ‘Rajput painting’ and expressed a particular fondness for the style, subsequently introducing the art form to the West. In his book Rajput Painting (published in 1916), he distinguished the works of this school from Mughal painting on the basis of subject matter and painting techniques. Indicating Rajput painting as an expression of Hindu philosophy, Ananda Coomaraswamy writes:

Their ethos is unique: what Chinese art achieved for landscape, is here accomplished for human love. Here if never and nowhere else in the world, the Western Gates are opened wide, the arms of lovers are about each other’s necks, eye meets eye, the whispering sakhis speak of nothing else but the course of Krishna’s courtship, the very animals are spell-bound by the sound of Krishna’s flute, and the elements stand still to hear the ragas and raginis. This art is only concerned with the realities of life; above all, with passionate love-service, conceived as the means and symbol of all Union.

Also read: Jamini Roy, one of India’s ‘national treasures’ who never sold paintings for more than Rs 350

Coomaraswamy classified Rajput painting into two broad categories: ‘Rajasthani’ and ‘Pahari’. The Pahari category pertains to pictorial art that originated and flourished in the hill states. Coomaraswamy further segregates Pahari painting into the ‘Kangra’ and ‘Jammu’ schools on stylistic grounds. By ‘Kangra painting’, he did not only mean the paintings produced in the state of Kangra but addressed the style of Pahari painting in vogue in the entire Kangra valley.

The renowned art historian William George Archer lived in India during British rule as a member of the Indian Civil Service. Later, in 1948, he gave his services as keeper of the Indian section in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Archer’s brilliant research on Pahari painting was path-breaking and found expression in his magnum opus Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills (1973). In two monumental volumes, he stylistically categorised Pahari paintings as developed in the various hill courts. His comprehensive research work contributed significantly to the study and appreciation of Pahari painting. Archer, during the initial phase of his research, chronicled in the monograph Indian Painting in the Punjab Hills (1952), expressed his views as below.

Elsewhere in India, painting had developed the expressive qualities of line and colour but nowhere outside the Punjab Himalayas were there achieved such exquisite renderings of the subtle ecstasies of romance. The style of painting originated in the state of Guler was later to become famous by the name of Kangra Kalam.

Archer also produced an important work towards the classification of the various schools and sub-schools, determining the periods of Pahari miniature paintings on the basis of style and school.

Art historian Mohinder Singh Randhawa had a profound love for Kangra painting. Randhawa had extensively explored and examined the major collections of Pahari paintings in possession of the descendants of the chiefs of the erstwhile hill states. He subsequently authored multiple monographs on the various themes of Kangra painting, including Kangra Valley Painting (1954), Kangra Paintings of the Bhagavata Purana (1960), Kangra Paintings on Love (1962), Kangra Paintings of the Gita Govinda (1963), Kangra Paintings of the Bihari Sat Sai (1966), and Kangra Ragamala Paintings (1971).

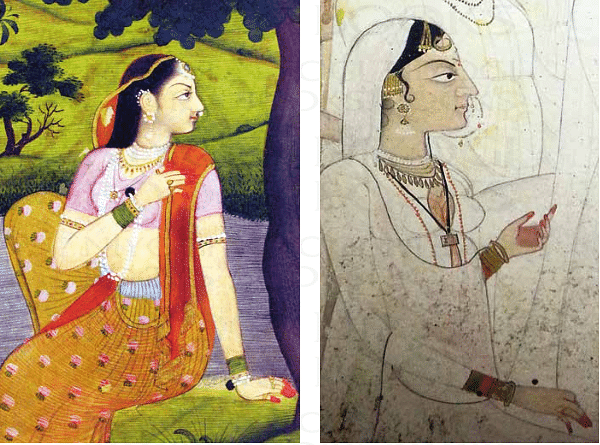

Another scholar by the name of Karl Khandalavala also conducted extensive research on Pahari painting, documented in his magnum opus Pahari Miniature Painting (1958). Khandalavala recognised the existence of the Guler school in Raja Govardhan Chand’s reign (1741–1773). Furthermore, he classified the early paintings, characterised by round faces (seen in the Bhagavata Purana series), as belonging to the ‘pre- Kangra’ or ‘early Kangra’ school. He drew attention to works featuring somewhat round faces, well-modelled, and shaded so judiciously that they possess an almost porcelain-like delicacy, with small upturned noses and carefully painted hair as per Mughal conventions, terming them the ‘Bhagavata type’.

Paintings produced during the last quarter of the 18th century have a tendency to show square faces, wherein the nose is almost in a straight line with the forehead, the tip of the chin is at an unusually long distance from the throat, the face is flat and devoid of modelling, the eyes are long, narrow, and curved, and the hair is an even mass of black colour, which he termed the ‘standard Kangra’ type. Pahari Miniature Painting is considered an encyclopaedia of Pahari painting because of its subject matter, chronological classification of the various styles, records of Pahari painters and their aristocrat patrons, and other historical evidence.

Also read: A McKinsey executive built a 1,000-piece Indian art collection. Now he’s selling

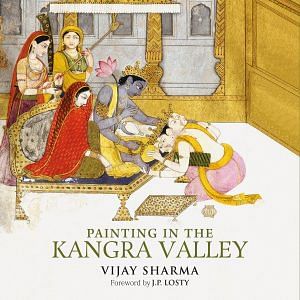

This excerpt and images from Painting in the Kangra Valley by Vijay Sharma have been published with special permission from Niyogi books.