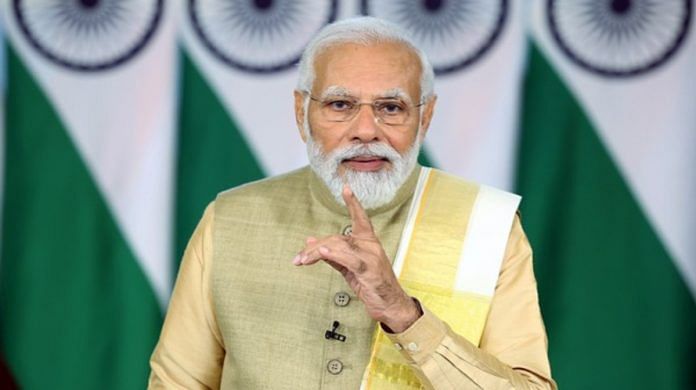

Now that the Ram temple consecration is done, Prime Minister Narendra Modi can turn his attention back to policymaking. And with the Interim Budget around the corner, he has quite an opportunity before him: he has a unique chance to elevate the maturity of India’s discourse. But to do this, he must ensure that the upcoming Budget speech doesn’t devolve into pre-election propaganda.

In other words, Modi must distinguish between the country and the ruling party – a distinction that is one of the hallmarks of a mature democracy.

Interim Budgets are distinct from normal annual Union Budgets. They are supposed to be simple votes on account that provide the government with funds to run the country until the general elections are decided and the new government announces a full-fledged Budget for the year. Even the term ‘Interim Budget’ isn’t official. Officially, it’s called a vote on account.

The politicisation of conventional Union Budgets largely began under Indira Gandhi in the 1970s. However, coming as they do just months before the Lok Sabha elections, it is also very tempting to use these Interim Budgets as vote-getting tools.

If PM Modi is confident about winning a historic third term, then he must also use this unique opportunity to decisively bifurcate economic and fiscal policy from the short-term aims of winning elections.

Move away from populism

To do this, Modi and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will have to break away from the relatively recent past. The Interim Budget of 2019, presented to Parliament by then-Finance Minister Piyush Goyal in February, included several announcements that were entirely populist in nature, and seemed aimed at the elections that year.

These included the PM KISAN scheme, under which regular doles were promised to farmers, the PM Shram-Yogi Maan-dhan, which provided pensions to unorganised sector workers, and a few significant changes to the income tax slabs to reduce the tax burden on those at the bottom of the pyramid.

Now, one is not saying these were unnecessary announcements. That’s a matter of debate. But the point remains that such an announcement could have been made earlier. It’s not as if the government doesn’t think through the fiscal impact months in advance. Instead, it chose to announce these decisions in the Interim Budget, just before the Lok Sabha elections in 2019.

This mindset, of aligning economic policy to the aim of winning elections, is also clear in how this government has been regulating the prices of fuel. An analysis by ThePrint has shown the remarkable ‘coincidence’ of fuel prices remaining unchanged just before assembly elections, only to be changed right after. It happens time and again.

There’s already some buzz that fuel prices—kept unchanged for more than two years now—will be lowered just before this year’s elections. Even if it is, the vehicle of this change should not be the Budget.

Even the announcement that the government’s free food programme would be extended for five more years was made by the Prime Minister during an election rally in Chhattisgarh in November 2023, a week before the state went to vote.

A few months earlier, in August 2023, the government announced a Rs 200 per cylinder subsidy on LPG for all customers, not just the poor ones. Here, the benefit of the doubt can be given to the government since it was still more than two months before the assembly elections in five states that year.

But knowing how strategically PM Modi and the BJP think about elections, it’s entirely possible this decision, too, was politically motivated.

Previous Interim Budgets—the ones before 2019—did keep elections in mind, but they were more circumspect about it.

For example, P. Chidambaram’s Interim Budget speech of 2014 announced subsidy expenditure of Rs 2.46 lakh crore, marginally higher than the Rs 2.45 lakh crore his government spent as per the revised estimates for the previous year.

In contrast, Goyal announced a 12 per cent increase in subsidy spending in his Interim Budget, with the biggest jump coming in the form of LPG subsidies.

One of Chidambaram’s decisions that could be seen as populist was extending the scope of the Central Scheme for Interest Subsidy on educational loans, which his government had announced in 2009.

Surprisingly, Pranab Mukherjee, in his Interim Budget of 2009, actually announced a lower subsidy outlay than his government had spent in the previous year. It’s another matter that the actual spending in 2009-10 was much more than what Mukherjee announced; that spending wouldn’t have impacted the 2009 Lok Sabha elections.

As far as I can tell, there weren’t any announcements in Mukherjee’s Interim Budget that could be directly linked to attracting votes.

Also read:

What can the government do?

Now, it’s not as if Interim Budget 2024 needs to be devoid of substance. There are a lot of substantial things the government can still do, which might even yield some positive electoral impact and will certainly help the country in the future.

It is important to address the alarming findings in the latest Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) about India’s abysmal education level. One of the many such findings was that one quarter of India’s teenagers struggle to read even a Grade 2 text. We are already facing an unemployment crisis. Unless we make our youth employable, this is only going to worsen.

This is one place the Interim Budget can help by making plain the government’s intention to bring education to the front and centre of its policymaking, should it return to power this year.

Another area that is perfectly designed for the short-term nature of the Interim Budget is aid to exporters suffering due to what’s happening in the Red Sea. Exporters are seeing a quarter of their shipments that would otherwise go through the Suez Canal held up and delayed by weeks and months. A lot of these exporters are small businesses that run on credit. They need help while the Red Sea issue persists.

The new government can re-evaluate whether this help is still needed when it presents its full Budget, but for now, the Interim Budget can certainly alleviate the issue for the next few months.

Returning to the issue of making a clear distinction between the nation and the ruling party, Modi could learn a thing or two from how the US views such things.

Speaking at the closing ceremony of the World Economic Forum in Davos, David Rubenstein, co-founder of the Carlyle Group, an American private equity investment company, made clear how his country is likely to view a fiscal move made too close to its elections.

“In our country, we have a presidential election (this year)…and as a result, the Federal Reserve wants to get its rate cuts out of the way before the presidential election is in full steam, because if you have rate cuts right before a presidential election, it will be seen as helping the candidate who is in the White House…so the Republican nominee will not be happy with that,” Rubenstein said.

Of course, Rubenstein isn’t a US government official and does not represent the Federal Reserve, but what he said on a global forum attended by world leaders is nevertheless important. It shows that some decisions need to be delinked from politics and taken solely in the interests of the nation.

Contrast this with how commonplace and accepted it has become for governments in India, at the Centre and in the states, to announce economic and fiscal decisions right before elections with the sole purpose of winning votes.

This needs to change. India is now more than three-quarters of a century old. It’s time to show some maturity, and a good place for the Modi government to start would be the Interim Budget 2024.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

It is just naivety to demand disjunction between economic and fiscal policies….

Mr Raghavan trying to sound sober & sane economic technocrat to advise Govt to pay attention to ASER report rather than expanding “doles”…. but this speak poorly of author’s disdain for political economy…

Govt CAN NOT embark on “transformative welfarism” ( of education & health) away from “transactional welfarism” ( of freebies) simply because ” transformative welfarism” requires much more fiscal profligacy at least on short to medium term , can engender macroeconomic instability ( like wage-price spiral) which inevitably will lead to breakdown of social contract between Indian capitalists & Ruling govt..WHICH THIS GOVT CAN NOT AFFORD

In fact this breakdown of social-contract due to macroeconomic instability of UPA regime is one reason for its debacle as MGNREGA probably inspired some wage-price spiral post 2010….

As if Modi will follow whatever is written here… Please stop dreaming….