India has one of the world’s largest militaries, but veterans and their families form only 0.6 per cent of the electorate.

The next parliamentary elections in India are likely to reanimate the discussion on the politicisation of the Indian military. Veterans were specifically mobilised before the 2014 elections by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on the issue of one rank, one pension (OROP). But when the party dithered in the implementation of the scheme, it sparked protests in 2015. In 2018, the decision by the government to open cantonment roads to civilian traffic saw the revival of agitation politics among veterans on social media.

Most extra-institutional forms of politics like pressure groups and protest movements are regarded with concern in democracies because they are interpreted as a failure of formal, institutional politics. Concern turns into alarm when the military veterans protest. Veterans are often linked to serving personnel, and protests, it is feared, exposes the military to the danger of politicisation. As long as veterans mobilise on issues related to the military, they resemble other pressure groups in India’s protest-filled democracy and do not necessarily pose a danger to the democratic fabric. Veterans actually have much to lose by developing a partisan tilt.

Revered, but institutionally weak

Institutionally, the three services in India are without much heft to pursue their interests in the corridors of power. Observe the position of the Prime Minister’s hand-picked Army chief in a popular power list published by The Indian Express. Among the 100 Indians perceived to be most powerful in 2018, the Army chief ranked 41st. The two other service chiefs did not even feature in the list.

The view from the legislature is not encouraging either. Veterans barely register a presence in Parliament. The membership of two former army officers, General V.K. Singh and Colonel R.S. Rathore, in the cabinet masks a bleak representation record. Less than 1 per cent, only 3 out of India’s 543 members in the 16th Parliament, had served in the military. Our analysis of the data from the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) shows that out of the total 8,794 candidates in the 2014 parliamentary elections, only 28 had listed themselves as ex-military.

Also read: First OROP, now cantonment roads- India sees rise of military as political pressure group

Compare this number with two other democracies that also have an all-volunteer force, where the military accepts civilian supremacy, and in which the military remains a revered institution. Currently, in the United States Congress, 100 out of the 535, or 19 per cent of members, and in the British parliament 51 out of the 650, or 8 per cent of members, have served in the military. Besides limiting their role as stakeholders in India’s democracy, the absence of veterans in the Indian Parliament deprives the armed forces of informed advocates in the legislature and contributes to the scarcity of military expertise available for lawmaking and oversight responsibilities.

The veterans’ narrow electoral footprint also constrains the military community’s influence. At 1.4 million strong, India has one of the world’s largest militaries, but veterans and their families form only 0.6 per cent of the 814 million electorate. Outside a few north Indian states like Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, and Uttarakhand, (states that according to the Ministry of Defence, send a disproportionate number of their residents to the military and are home to 35 per cent of veterans), ex-servicemen are limited in their ability to emerge as a consequential vote bloc on their own. Still, like their counterparts in other democracies, veterans are uniquely placed to act collectively as a pressure group, and numerically the participation threshold for organizing protests is much smaller than that of successfully contesting elections.

A readymade pressure group

Despite the military’s weak institutional clout, the veterans are more easily organised than other groups. Its members are strongly socialised into a military identity. Bonds with fellow personnel during military service are sustained even after retirement through ex-servicemen organisations, regimental networks, and separate residential communities. Veterans are also digitally networked on multiple social media platforms. On WhatsApp, an officer writing from any corner of India is able to reach a national audience of military veterans without the assistance of a television channel or newspaper. They share a core set of interests as ex-servicemen.

Value of protests

The military veterans’ protest and petitions serve three important functions. First, protests signal discontent with the governing structure and alert it to the veterans’ grievances. Second, in a competitive party system, protests open up the possibility of interests finding representation through institutional channels. After all, protests generate leaders who can either join political parties to contest elections, or endorse sympathetic parties and candidates. The OROP movement, for example, was not created by the BJP. The movement endorsed the party in exchange for its promise to implement the policy.

Also read: He had everything, but Modi missed a brilliant chance to fix the messy Indian military

Third, mobilisation of this nature also serves a monitoring purpose. It aims to hold the military leadership accountable for the advocacy role it is entrusted with on behalf of the rank and file of the organisation as well as the large community of veterans. At the height of the OROP standoff in 2015, alarmed by the veterans’ protest, former service chiefs wrote to the Prime Minister and the President asking them to swiftly resolve the dispute. Similarly, the social media-based protest on the cantonment issue compelled the representatives of the Army Welfare Association to meet with members of the army fraternity to assuage their discontent. In this sense, the mobilisation of the veterans as a pressure group in pursuit of interests represents routine democratic politics.

The danger of politicisation

This is not to say that the agitation politics of the veterans do not pose the danger of politicisation of the serving military resulting in a partisan tilt as Srinath Raghavan has warned. In a competitive party system, a partisan alignment disadvantages the military and the veterans, and is therefore not a foregone conclusion.

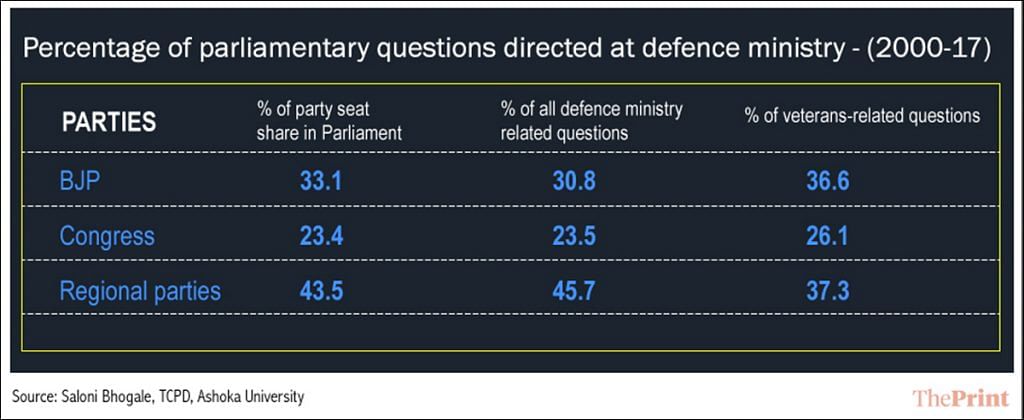

The parliamentary questions to the defence ministry since 2000 show that the national as well as the regional parties from across the ideological spectrum engaged with defence issues and veterans concerns. In this period, members of the Lok Sabha asked a total of 7,505 questions to the defence ministry. Out of these, 30.8 per cent were asked by the BJP, 23.5 per cent by the Congress, and 45.7 per cent by members of different regional parties. The same pattern is observed for questions related specifically to ex-servicemen. It is noteworthy that these questions are mostly proportionate to the number of MPs belonging to these parties. The evidence presented in Table 1 clearly suggests that aligning with a single partisan identity makes little sense for military veterans, especially when such a large set of parties take interest in ex-servicemen affairs.

Table 1:

By doing so, they lose the bargaining power they possess because of the competition for their vote. As former members of a national institution, partisan neutrality also helps the military veterans retain broad public support. If the military or the veterans came to be viewed as a particular party’s permanent ally, the social trust in the institution is likely to shrink.

Institutionally constrained to pursue their interests, the military veterans are nevertheless well-positioned to act as a pressure group. It remains to be seen whether this pressure group politics hurts the military’s apolitical image.

Amit Ahuja is an associate professor and Rajkamal Singh is a doctoral student in the Department of Political Science at University of California-Santa Barbara.

Inindia the military persons are expendable. Daily some soilders will be dying in fighting terrorism. But MPs and MLAs are precious. They are born only to serve themselves and their families. So don’t ask polititians to serve in military.

Politicians as a class are cowards.

Do you expect them to shed a drop of blood in the defense of our motherland?

Send them all for six months rigorous training in military and in farming

That only tells you that Indian military personnel are not suited for the corrupt life of habitual liars and family owned political parties. That is not such a bad thing that military people are not interested in politics. Just look at McCain of USA. The clown was a prisoner and made a career making people think that he is a hero.

This is India. Not USA or Israil.

The most recent data from the 2010 Census shows that only seven percent of Americans have served in the military, while veterans make up 20 percent of the current Congress. In 1971, 73 percent of members of Congress were veterans, but veterans made up fewer than 15 percent of the American population.

where on the earth MP”S have military experience ,stop publishing non sense