One of the unresolved puzzles from the 1962 India-China war is why the Jawaharlal Nehru government, despite being acutely aware of India’s military weakness, adopted the infamous Forward Policy in December 1961—a policy widely accepted as having placed India in an untenable military situation on the northern border. The short answer is that Prime Minister Nehru believed the international environment favoured India in its dispute with China.

Balance of power

Growing confidence that the global balance of power was tilting in India’s favour had become the general belief in Delhi by the turn of the 1950s. India-US and India-Soviet relations were developing as rapidly as China’s ties with the superpowers were deteriorating. After 1956, there had been an important US policy shift toward South Asia and an attempt to engage India by supplying large economic assistance to support its Second Five-Year Plan, which aimed to foster and promote industrialisation in the country. In December 1959, then US President Dwight D. Eisenhower encouraged Nehru to take a firm stance vis-à-vis China. Eisenhower assured Nehru that the US would not let Pakistan take advantage of India while it was dealing with its northern frontiers.

The Soviets, too, had chosen to reveal their differences with China when they began publicly taking a neutral position on the India-China dispute while privately berating the Chinese for their reckless conduct in Tibet and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s skirmishes in 1959. The first clash occurred in August 1959 at Longju, in the eastern sector, and then another one in October 1959 at Kongka Pass in the western sector.

After 1959, the Indian government began to perceive the superpowers’ tilt in favour of India, on the dispute, as a restraint on Chinese behaviour. For example, in September 1959, then Defence Minister V.K. Krishna Menon felt that the Chinese were moderating their rhetoric on India after the Soviets had advised Beijing “to be conciliatory.” One could view it as ‘soft’ external balancing, similar to how India leverages third parties to quietly weigh in on geopolitical issues today. In 1959, India made requests to the Soviets to moderate Chinese behaviour. Soviet support was expressed in the famous TASS statement of 9 September 1959, which by taking a neutral position on the dispute with India, broke ranks with the Chinese. It was a dramatic international development in the Cold War as China’s differences with the USSR came out in the open.

Also read: Not just Nehru, China’s 1962 war on India also a counter to Mao’s secrets

China under pressure

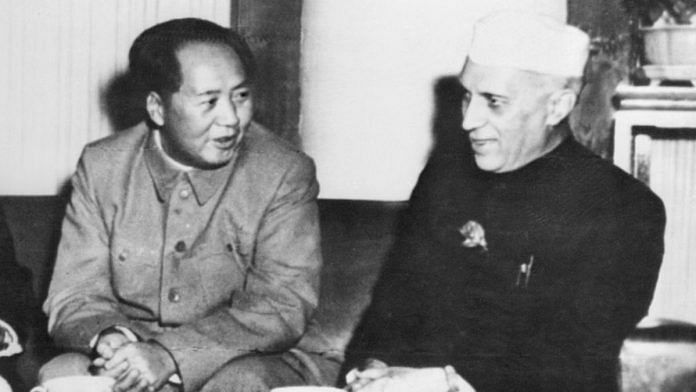

Nehru sensed that Moscow’s disapproval of Chinese aggression with India and the Soviet ‘middle attitude’ of neutrality was a major development and “an indirect criticism of the Chinese position.” Nehru felt Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to Beijing would probably raise the “question of the India-China border.” Indeed, during their contentious October 1959 meeting, Khrushchev admonished Chinese supremo Mao Zedong and other leaders for escalating the border crisis with India. Mao had felt enough heat to have assured the Soviet leadership: “You will see for yourselves later that the McMahon line with India will be maintained, and the border conflict with India will end…The border issue with India will be decided through negotiations.” Almost immediately, Indian officials felt this change in attitude as senior Chinese leaders, including Mao, showed “in many ways that they want to be friendly and have discussions with us in the near future.” The Chinese wanted to ‘“step down” as they wanted to do it “without loss of face.”

For the most part, Nehru’s balance of power approach was focused on publicly signalling that India had powerful friends. For instance, in November 1959, Nehru remarked in a press conference that the border problem with China would “undoubtedly” come up during conversations with Eisenhower during his visit to India. When asked about India’s future approach to military assistance from the great powers, Nehru noted that in the unfortunate scenario of a war between India and China, “such a thing will not remain an isolated, limited affair. The world is dragged into it.” The following year, Nehru privately remarked that the US’ fear of China had led it to view India “as a balancing factor” and therefore “more inclined to help” Delhi.

Nehru felt that China would not risk a major war with India because “the Soviet Union was dead opposed to it.” More broadly, Nehru hoped that this public show of close India-US and India-Soviet relations would influence China and moderate its behaviour. He also felt that a US-Soviet détente would serve as a ‘check’ on China.

Also read: Why Modi’s bouts with China will make history judge Nehru kindly

Delhi’s false confidence

In retrospect, however, all this was utterly insufficient to help overcome India’s asymmetry with China and could have shaped Delhi’s false sense of confidence in its subsequent dealings with Beijing. We also now know that the Soviet Union had informed India that they had done “as much as they were able to” in cautioning the Chinese to exercise restraint. The Russians were clearly not in a position to dictate Beijing. When, in February 1960, Nehru brought up the China issue and suggested an informal Soviet role in narrowing India-China differences, Khrushchev’s response was instructive: “We would not like our relations with either of our two friends to cool off.” Khrushchev declined a mediatory role and advised a bilateral approach, “It is possible for two wise men to agree among themselves. If the third man appears on the scene, he will only make matters worse”.

Nehru, however, remained unruffled. In 1959, to the Lok Sabha, Nehru expressed a sense of confidence that the trouble with China had come at a time when India “had the prestige” and “wide friendship in the world today.” After 1960, India was receiving generous material support from both the superpowers even as China was getting increasingly isolated, which emboldened the Nehru government to overestimate India’s importance in the eyes of Washington and Moscow. The overall effect was that it created a belief that Chinese behaviour would be restrained and simultaneously reduced incentives for India to adopt a more pragmatic negotiating position. In the famous April 1960 summit between Prime Minister Nehru and Premier Zhou Enlai, India rebuffed a Chinese offer to settle the boundary on reasonable terms.

Another anecdote exemplifies Indian thinking right up to the eve of the war. On 13 October 1962, a week before the outbreak of hostilities, in an exchange between Indian Foreign Secretary M.J. Desai and US Ambassador John Kenneth Galbraith, Desai remarked that there “would be no extensive Chinese reaction because of their fear of the US – “It is you they really fear”. Of course, by that time and unknown to Delhi, the Chinese had received assurances from both the US—regarding a possible threat around the Taiwan Straits—and from the Soviets, who were focused on the Cuban missile crisis, thereby freeing the PLA to focus on the Indian front.

Zorawar Daulet Singh is a historian and author of ‘Powershift: India-China Relations in

a Multipolar World’. He tweets @z_dauletsingh. Views are personal.

This article is part of the Remembering 1962 series on the India-China war. You can read all the articles here.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)