It is now exactly 60 years since tens of thousands of regular Chinese troops poured across India’s northern borders, from Ladakh in the west to then-Northeast Frontier Agency (NEFA) in the east. But, to the surprise of many, after little over a month of fighting in 1962, and having inflicted a humiliating defeat on the Indian forces defending the border, the Chinese declared a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew their troops to pre-war positions.

Nehru’s fault?

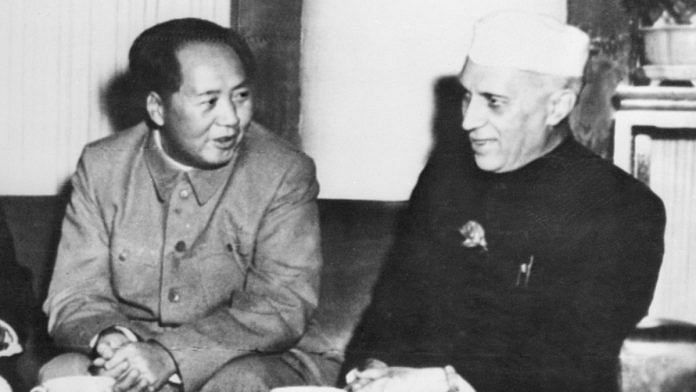

There are many theories as to why the Chinese attacked and acted as they did, and for years Neville Maxwell’s India’s China War, which was first published in 1970, dominated the narrative. According to Maxwell, India was to blame and referred to a classified Indian intelligence document compiled by Lt Gen. TB Henderson Brooks and Brigadier Premindra Singh Bhagat to back up his claim. The war was provoked by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s Forward Policy and the construction of Indian defence installations not only on but even beyond the line that separates NEFA, now Arunachal Pradesh, and Chinese-held Tibet. But the Henderson Brooks-Bhagat report doesn’t say that. It merely states that Nehru’s government didn’t give the Army the necessary tools to implement the Forward Policy, and that there was a lack of cooperation between the government in New Delhi and the military in the field.

Furthermore, it falls on its absurdity that such a massive attack could have been prompted by Nehru’s Forward Policy, which was decided upon at a meeting in New Delhi on 2 November 1961—less than a year before the war. If Maxwell is to be believed, China would have been able to build new roads and military camps in the area during that time, and move at least 80,000 of troops and tonnes of supplies, including heavy military equipment over some of the most difficult terrain in the world. Those troops would also have to be acclimatised to high-altitude warfare and supply lines had to be established and secured to the rear bases inside Tibet. Furthermore, Brig. John Dalvi, who was captured by the Chinese and remained a prisoner of war until May 1963, discovered that the Chinese had erected prisoner-of-war camps to hold up to 3,000 men. Chinese interpreters who knew all major Indian languages were present in those camps. Chinese preparations for a war with India must have begun years before the attacks took place, not sometime after the November 1961 announcement in New Delhi.

Also read: Why Modi’s bouts with China will make history judge Nehru kindly

Was Zhou Enlai flexible?

According to another theory, suggested by Avtar Singh Bhasin in his 2021 book Nehru, Tibet and China, the 1962 war could have been avoided if Nehru had been more willing to listen to China’s version of the border dispute. While Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai showed some degree of flexibility in his letters to Nehru, the latter remained steadfast in his belief of where the boundary should be. Nehru’s “rigidity”, Bhasin argues, “stood in the way of finding a solution through negotiations and discussions by sitting around a table.”

Bhasin’s book is meticulously researched and brilliantly written, but fails to take into account that Zhou’s diplomatic niceties stood in sharp contrast to what had been written about Nehru in Communist, Chinese-language publications. In an editorial on 2 September 1949, the Hsin Hwa Pao stated after the Tibetan authorities in July of that year had decided to expel Chinese citizens from the country: “The affair…was a plot undertaken by the local Tibetan authorities through the instigation of the British imperialists and their lackey Nehru administration in India.” In August and September 1949, Shijie Zhishi, a Shanghai-based fortnightly, denounced Nehru as a “running dog of imperialism” and a Chiang Kai-shek-like “loyal slave” of the enemies of the revolution.

Then there is the official Chinese version, most recently expressed by writer Zhang Xiaokang in an essay published on 13 January this year “to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the self-defence counterattack on the Sino-Indian border in 1962.” Zhang, in some ways echoing Maxwell’s version of events, stated that the Chinese army, “won the battle, completely crushed the Indian invasion army’s rampant attack [and] wiped out the main force of the Indian troops participating in the war.” Many, even the most neutral observers, would argue that the less said about that fanciful account of the 1962 war the better.

Also read: ‘Expansionist’ Nehru, Tibetan autonomy, ‘New China’ — why Mao went to war with India in 1962

Look at China internal problems

So why did the Chinese attack, and when was the decision to launch a war against India taken? Basically, there were three reasons behind the decision. The first was that India had granted the Dalai Lama asylum after his flight from Tibet in March 1959 and allowed him to set up a government in exile, first in Mussoorie and then in McLeod Ganj. At a meeting on 25 March 1959, as the Dalai Lama was still on his way to India, China’s supreme leader Mao Zedong as well as Deng Xiaoping decided that “when the time comes, we certainly will settle accounts with them [the Indians].”

The attack must also be understood in the context of internal problems in China at the time. In 1958, Mao initiated the disastrous Great Leap Forward to modernise China. By 1961, anywhere between 17 and 45 million people had died as a result of his policies, which caused a famine rather than, as intended, any rapid industrialisation. Mao was discredited and, very likely, on his way out. He must have felt that he had to regain power — and the best way to do that would be to unify the nation and especially the armed forces against an outside enemy. India was a “soft” target because it granted the Dalai Lama asylum and then there was the issue of the border that China did not recognise.

The third reason was that until the outbreak of the 1962 war, India and especially Nehru had been the main voice of the newly independent countries of Asia and Africa, which was clearly demonstrated at a conference in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955. The Non-Aligned Movement was born, Zhou was present at the meeting — but Beijing had other ideas plans and ideas. It wanted to be the “revolutionary bulwark” of what later became known as the Third World, and India had to be dethroned from the position it had held throughout the 1950s. In that respect, the 1962 war worked to China’s advantage. Nehru died a broken man in 1964 and Mao became the icon of many Asian and African liberation movements.

There may not be another all-out war in the Himalayas, but China’s intransigent attitude and behaviour in the South China Sea and its increasingly provocative incursions into the Indian Ocean could well lead to serious regional conflicts. Then there is the question of China as the world’s biggest dam-builder, with rivers flowing from Tibet and Yunnan into other countries downstream, including India, without even consulting affected countries. The capitalist China of 2022 may not be the same as it was under Mao’s dogmatic rule, but it has not given up its ambitions to become the dominant power in Asia, perhaps even in the world.

Bertil Lintner is a Thailand-based journalist and author of China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World. Views are personal.

This article is part of the Remembering 1962 series on the India-China war. You can read all the articles here.