Unloved, unknown, and moribund is the Indian liberal. In this country, which is religious, socially conservative, and long hostile to the free market, the main tenets of liberalism — individual rights in matters of enterprise, belief, bodily autonomy, and other core competencies — have long taken a back seat. The individual has never been at the centre of Indian political thought, and the idea of liberalism as we think of it in the modern sense has never found consistent traction among politicians.

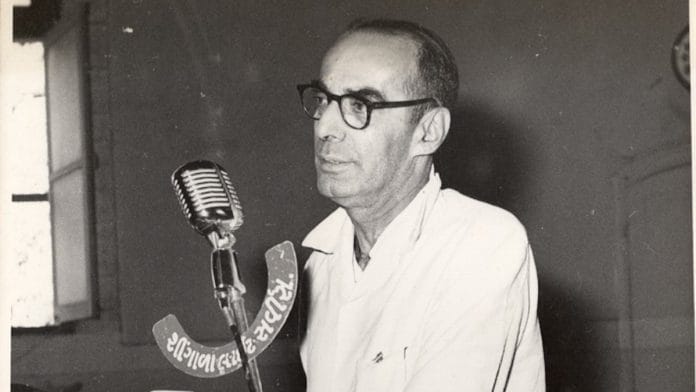

Minocher Rustom “Minoo” Masani, a freedom fighter, three-time Member of Parliament, editor, and social activist was an exception to this general rule. Through his speeches and articles, Masani became the voice of the individual in 20th-century India — a fierce defender of free choice in a society governed by conservative social mores and statist economics. He and his ideas are relatively obscure today in zero-sum India where the ideal of individual autonomy has been left to putrefy in a political landscape dominated by sectarian hatred and mob psychology. The poverty of imagination that plagues India has left us largely bereft of original political thinking to respond to the deterioration of personal freedoms that has occurred in recent years. It is precisely at this moment that Masani’s work deserves a second review. Although ephemeral, Minoo Masani’s career marked a key moment in Indian history, establishing a liberal opposition to the statist politics of the time and surpassing the socialism, nationalism, regionalism, and caste politics that have shaped it since.

Founding ‘liberal’ India’s feet

What little memory of Minoo Masani remains stems from his status as a founding figure of the Swatantra Party, which fought its first general election 60 years ago in February 1962, winning 18 seats. Masani had been elected to Parliament initially as an independent candidate five years prior. The Swatantra Party, which dissolved after its capitulation in the 1971 election, is, in turn, best remembered for its fierce advocacy of free-market economics – an outlier at a time when Nehruvian socialism was all-encompassing. In its inaugural electoral campaign, the party campaigned on an anti-statist front, drawing together a coalition of traders and landowning peasants who feared government encroachment on commerce and land use. The party’s senior figures – Masani, K.M. Munshi, N.G. Ranga, among others – worked with regional leaders from local parties to drum up support and form anti-Congress fronts.

In Masani’s view, Jawaharlal Nehru’s idea of a socialist state designed to oversee the transition from colonial rule to self-reliance would inevitably lead to increased political control. The good intentions of the country’s leaders would prove useless in the face of this unalterable truth, and he claimed in a lecture held in Mumbai: “They believe they can preserve political freedom while hacking away merrily at its economic foundations.”

Masani was a committed democrat who was convinced that freedom and prosperity were irrevocably intertwined, noting that countries with “a free press, considerable dissent, and periodic elections” were also those where consumer freedom was the highest. Although painted by his opponents as a free-market fundamentalist, he was not opposed to the welfare ideals that made up the core of Nehruvian policy. Instead, he viewed the State control of welfare delivery as inimical to effective poverty alleviation. Masani’s distaste for Leftist politics led him to become a leading figure in the American-backed, anti-Communist Congress for Cultural Freedom’s expansion into Asia during the 1950s.

Also read: Masani, Rajaji and Shenoy — the free-market troika that challenged the Nehruvian State

Not a dogmatist, but defender of individual freedoms

To view Minoo Masani as merely a strident capitalist or a dogmatic right-winger, however, would be reductionist and overlook his most important contributions to Indian political thought. His commitment to individual liberty extended far beyond the scope of economic freedom. Far from being a single-minded free-marketeer, he was deeply invested in defending the personal autonomy of Indians in many different forms. His philosophy was united by one significant strand: a belief in the fundamental superiority of individual choice over State control and societal objection.

Masani’s political and social work is marked by a preoccupation with increasing personal autonomy. In founding the Society for the Right to Die with Dignity in 1981, Masani advocated for the legalisation of assisted dying. At that time, the practice was illegal everywhere except in Switzerland and remains a question of raucous moral debate even today. Masani argued that the right to choose the circumstances of one’s own death should rest entirely with the individual, strongly supporting personal autonomy against societal objections and “people talking of life being sacred in the abstract”.

He was also a strong supporter of abortion rights, being an outspoken backer of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971 that legalised abortion, and he is also claimed to have wanted to introduce a private member’s Bill in Parliament several years before the law was passed. He criticised bans on religious conversion, seeing them as trampling on personal freedom, and would no doubt have been horrified by the glee with which the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) now pursues such laws.

In his advocacy for the rights to assisted suicide, abortion, and religious conversion, Masani was expressing an inherently liberal, democratic outlook — that individuals alone should enjoy control over their lives, free from interference, and that advancing these rights through law was an effective way to expand and strengthen the autonomy of Indian citizens. Societal backlash was inevitable — attempts at progress provoking hostility is an immutable fact of political advocacy. But Masani’s trenchant defence of the individual provided an important polemical voice at a time of deep-seated social conservatism.

Also read: Swatantra Party had a lot to say on China after 1962. If only Nehru had heard them

Some hiccups, but Masani stands tall

We might condemn Minoo Masani for the economic inequalities inherent in many of his plans due to his inability to look past his own privileged circle and engage with the difficult realities of poverty-stricken nascent India. Indeed, the public did not embrace him, and the Swatantra Party did not achieve lasting political success. But one thing is clear: no Indian leader, before or since, has been as committed to the protection of individual autonomy in public or private life.

To put “the individual right in the centre of the picture” as Masani had, may seem an alien concept in a land where extremists seek to silence any expression of personal autonomy that deviates from their ideals. Today’s political landscape values group identity, particularly religion, and discards the individual as an afterthought. But it need not be this way.

Reading Minoo Masani today reminds us not to abandon the individual as a political and rational being. When we neglect to protect and promote personal autonomy, we encourage tyranny and exclusionary politics to rush in and fill the void. The Swatantra Party and Masani are dead — the life-giving freedom for which they stood must not follow.

Aditya Sharma studies 20th-century Indian political thought at Cambridge University. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)