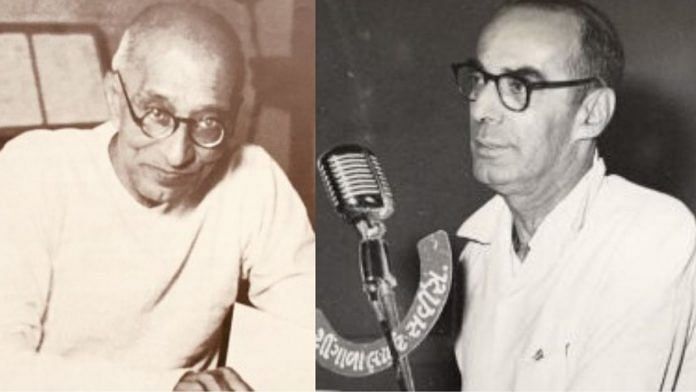

The recent incursions by China into the Indian territory has been compared with 1962 and 1967 by many military historians. But what is not so widely known is how independent India’s first classic liberal party, the Swatantra Party’s leaders such as C. Rajagopalachari and Minoo Masani reacted to the foreign policy challenge and spoke of preserving liberty amid the national security threat during the 1962 war.

For Swatantra leaders, the 1962 war with China vindicated their distrust of Communism, criticism of Jawaharlal Nehru’s non-alignment policy, and advocacy of cordial relations with the Western bloc. They even foresaw what is today known as the threat of a ‘two-front’ war with China and Pakistan.

The Swatantra Party’s apprehensions of the Chinese intent made it critical of Nehru as well as of then defence minister V.K. Krishna Menon who, its leaders believed, imperilled national interest. Military setbacks at the border prompted the parliamentary board of the Swatantra Party to take an offensive approach against China. The recommended measures included the provision of best weapons to the army, active involvement of air forces as support measure, and enactment of anti-aircraft defences. There are at least two possible arguments why.

Historian Srinath Raghavan makes it clear in his analysis that the gradualist escalatory approach of Nehru failed to work in China’s case. By extension, an offensive military and diplomatic strategy might have plausibly succeeded. Such a claim is supported by the second argument on the relative power gap between India and China in 1962. According to Rajesh Rajagopalan, professor of international politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, in terms of GDP, the gap between the two countries was not significant. Additionally, even the GDP multiplied by GDP per capita approach to measure power would pretty much yield the same outcome. Hence, India’s defeat in 1962 was partly an outcome of the failure of converting latent (economic) power into military power. This failure stemmed from a moderate policy approach that sought to avoid confrontation with China.

For Swatantra Party leaders, their advocacy of a firm stand on China came as a corollary to the critical targeting of Nehru’s policy. Speaking in the parliamentary debate on 8 November 1962, N.G. Ranga chided the Nehru government for its failure in the elementary duty of defence preparations. He further laid out the demand for the Chinese to go back to their positions of 1957 as a prerequisite for any diplomatic negotiation. Aware of the problem of inadequate military supplies, both Ranga and Masani insisted on procuring military aid from friendly countries in the Western bloc.

Also read: No accident India forgot Swatantra leader & my father Minoo Masani, the beef-eating Parsi

Foreign policy

The Swatantra Party’s approach to foreign policy was characterised by the criticism of non-alignment as both policy and movement, recognition of China as the primary strategic challenge in the neighbourhood, distrust of the Communist USSR as a revolutionary State, and vocal support for the Indian tilt towards the US-led bloc in the Cold War.

Writing in the 11 November 1962 issue of Bhavan’s Journal, Swatantra politician K.M. Munshi criticised Indian foreign policy for its sense of righteousness and complacency. The self-righteous adherence to non-alignment, wrote Munshi, had come to naught in the moment of crisis. Masani’s earlier speech in Bombay (now Mumbai) on 31 October 1962 laid bare the disappointing fence-sitting of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) bloc countries in the wake of Chinese aggression. He noted that the very few voices of support coming from the Afro-Asian block included that of Malaysia, Tunisia, and Ethiopia. The non-aligned posturing of India had not prevented Soviet Union premier Nikita Khrushchev to take the side of China on ideological grounds. Referring to the Pravda editorial of 25 October 1962, which affirmed the China-Soviet bonhomie based on a shared ideology, Masani warned against misplaced hopes of USSR aid.

In their advocacy of alignment with the West, Swatantra leaders also anticipated and sought to stave off possible criticisms. For Rajagopalachari, the policy of non-alignment might have been justifiable during the Cold War, but not during a ‘shooting war’. Ranga, in his earlier mentioned speech in Parliament, argued that the unconditional support from the US should dispel any charge of subordinating national interest to the whims of great powers. In his Bombay speech, Masani had also singled out the cases of the NAM bloc countries, including Yugoslavia, Egypt, and Indonesia, all of which had taken military aid from the US. Thus, the acceptance of military help from another country would not contravene the policy of non-alignment.

It fell upon Masani to explain what Munshi characterised as complacency in Indian foreign policy. Masani’s charges against Nehru’s mishandling of India’s foreign policy included the appeasement of Chinese aggression, failure to join the United Nations forces in Korea, betrayal of Tibet, and objection over the Dalai Lama’s appeal to the UN Security Council in 1950. In an ‘I told you so’ moment, he also drew attention to the November 1951 debate in the Provisional Parliament in which he and other leaders, including Hriday Nath Kunzru, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, N.G. Ranga, Frank Anthony, had warned of the challenge posed by the Chinese invasion of Tibet.

In recent debates on Indian strategy in the fraught neighbourhood, the challenge of two-front war looms large. Acutely aware of the problem in the 1950s-60s, Swatantra Party leaders argued for resolving tensions with Pakistan to recalibrate the border defence mechanism towards China. In their approach towards the northern frontier, they thus differed from defence minister Menon, who saw Pakistan as the major threat. Noticeably, then-Pakistan President Ayub Khan’s 1959 proposal for a joint defence arrangement for the Indian subcontinent against Chinese expansionism had come as a suitable mechanism for implementing the Swatantra standpoint. However, Nehru had outright rejected the proposal citing his adherence to non-alignment.

For Rajagopalachari, it was the unviable defensive challenge of a two-front war, the identical destiny of India and Pakistan in the long run, and the shared threat perception of Communism that necessitated such an arrangement. In the middle of the 1962 war, Masani argued that Pakistan’s incentive for supporting a joint endeavour with India lay in saving East Pakistan, which could have become a Chinese target if it had moved to attack Assam.

Also read: Why Minoo Masani & Atal Bihari Vajpayee opposed Indira Gandhi’s bank nationalisation

Democracy at war

Insofar as the Swatantra Party espoused a classic liberal agenda of the free market, individualism, and democratic polity, the implications of national security falling into a crisis for the state of liberty did not escape its attention. “Inevitably, in any war, the first casualty would be democracy. That should not be allowed,” proclaimed Rajagopalachari in his public address in Madras (now Chennai). He further pointed out the steps already taken in that direction including the proclamation of war emergency and suspension of certain constitutional protections to people. The parliamentary board of the party also stressed on the need to closely scrutinise the Defence of India Ordinance, Bill, and Regulations to prevent deterioration of fundamental rights and democratic process.

Ironically, though, the Swatantra Party’s concern for liberty and democracy did not extend to Communist outfits. Suspicious of the revolutionary character of the Communist movement, Swatantra Party politicians deemed them as a potential threat to national security and dubbed them as ‘fifth columnists’. Rajagopalachari criticised the Madras government for inducting Communists into the State Defence Aid Committee. Masani, on the other hand, applauded the West Bengal, Kerala, and Gujarat governments for keeping Communists away from such initiatives.

The Swatantra Party demand for banning the Communist Party of India (CPI) stemmed from the prevalence of ‘Cold War liberalism’, which articulated a grand narrative of the global struggle between totalitarian Communist states and the free world of capitalist democracies. The Cold War liberals professed to defend democracy, rule of law, and civil liberties at home and advocated for the same in the Communist sphere of influence. Faced with the pressing challenge of an alternate vision of global order, especially attractive to the newly independent so-called ‘third world’ countries, the liberal anxiety ironically appeared in terms of demand for curtailing political rights of Indian Communists. The limits of Cold War liberalism were apparent in Masani and Rajagopalachari’s apprehension of a Communist takeover of India with the active role of homespun revolutionaries. The solution to them was deploying State power to curtail civil liberties of a particular political dispensation.

To be sure, the liberal perception of existential threat was partly due to the ideology-driven Chinese-Soviet nexus during the 1962 war as well as the export of revolutionary pronouncements from both Moscow and Beijing, which were duly lapped up by Indian Communists. Apart from this, the Swatantra Party leaders were rightfully concerned about the deleterious implications of a ‘national security state’ for political and civil liberties. The parliamentary board of the party reiterated that the “Opposition should carry out its responsibility of free and frank criticism whenever it is necessary”. They also demanded public provision of information regarding war efforts as well as permission to journalists to report from the war frontier. Stressing on the need for non-partisan defence effort, Rajagopalachari argued in favour of an all-party government similar to Western democracies during war times.

The emulation of Western democracies was further evident in Masani’s frequent use of the British Labour Party’s trope of constructive opposition to the Chamberlain government in 1940, despite the apparent threat of Nazi blitzkrieg. During the May 1940 debate in the British Parliament, Labour MPs, as well as a section of the Conservative Party, had vehemently opposed then-PM Neville Chamberlain for the Munich appeasement of Hitler. It was only after the resignation of Chamberlain on 10 May that the Labour Party agreed to form a coalition government with the Conservative Party.

Even so, Masani pointed out that “a large number of Labour MPs were allowed to sit in Opposition and to criticise the government and the policies” during the war. As historian Ramachandra Guha writes in his book India After Gandhi, socialist leader J.B. Kripalani also referred to British conservatives compelling Chamberlain to resign in his much-applauded speech in the Indian Parliament on 11 April 1961. The implication of such pleas was clear: a democracy at war need not see a thriving opposition and free press as impediments to war efforts. Constructive criticism of the ruling party made in the national interest would enable course correction and strengthen the nation against adversarial forces.

Also read: 60 years ago, a Right liberal Swatantra Party had challenged Nehru’s socialist Raj

Relevance today

Recognising the endurance of threat posed by China even after the unilateral ceasefire, Rajagopalachari wrote in the Swarajya magazine that the future trajectory of geopolitics “clearly demands a great and drastic change of policy in order to build up a balance of power to preserve peace — and the independence of nations — in Asia”.

In taking a realistic approach to international politics based on the logic of balancing, Rajagopalachari was matched by Masani. Speaking in Parliament in 1965, Masani anticipated the Quad-based security coalition, which is now being touted as the balancing response to China’s rise in the Indo-Pacific. His conception of the regional security arrangement in 1965 included India, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand along with other South-East Asian nations to defend Asian democracies against China. Apart from making the case for such external balancing and western military aid, he had also suggested in 1962 to bring the matter of Chinese aggression to the UN.

Further, in his 31 October 1962 speech, Masani borrowed the Kautilyan dictum of ‘the enemy’s enemy is my friend’, as described in nationalist historian Kashi Prasad Jayaswal’s Hindu Polity. The strategic application of the dictum for Masani lay in Indian support to the Taiwan-based nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. Defeated in the Chinese Civil War against Communists, Chiang had to leave the Chinese mainland for Taiwan. From his tiny island-state across the strait, he posed a perennial security threat to Communist rule in the Chinese mainland. Masani presciently saw that a military alliance with Taiwan would allow India to deter Chinese aggression due to the possible opening of a second front by Taiwan in case of war. To cement his case for close cooperation with Taiwan, he also brought up the history of Chiang’s support for Indian independence during World War II in his speech.

As the Indian foreign policy establishment gears up to deal with a powerful revisionist challenger in Asia, policy experts have suggested a slew of balancing measures as the way forward. These measures include closer alignment with the United States, institutional balancing, strengthening of ties with Taiwan, use of Tibet as leverage, and Quad-based security arrangement.

In the Swatantra Party’s response to the Chinese challenge in 1962, we find a precursor to all these elements of India’s potential balancing strategy. Moreover, contrary to what Swaraj India president and columnist Yogendra Yadav has argued, the Swatantra Party’s concern with preserving democratic rights and stress on constructive opposition amid a national security crisis ought to be emulated today. The lessons of history have the potential to guide Indian strategic policy.

The author is a student in the MA program in Politics (with specialisation in International Studies) at JNU’s School of International Studies. He has also worked with the Centre for Civil Society on its Indian Liberal Project (indianliberals.in) as an Indian Liberal Fellow. Views are personal.

Most of the leaders of the Sawatantra Party had more foresight of the international situation of that time and it’s consequences for the future in regards to India. While Nehru was concerned only about his personal image among the newly independent countries of the Third World. The leaders of the Sawatantra Party assessed the mentality of the communists in reality. Had India been governed by The Sawatantra Party, we would have been among the most developed country. We should thank NarsimhaRao for abandoning the Nehru-Gandhi Policy of pseudo secularism and following the path visualised by the great leaders of Sawatantra Party.

Nehru made many mistakes , is a well known fact today. His compulsions and mental make up on various subjects is not fully known. His weaknesses were many, but his tolerant policies were not vehemently opposed by the people he was surrounded with.It is an equal shame on them. Today Modi and Shah are being accepted by us. Who is opposing them. The majority is silent. Why criticise them in whatsApp columns. Go to streets and raise your voice . The silent majority did not involve themselves, because they were too busy to fend for themselves. They had no access to the happenings at the National level.EDUCATE THE MASSES.LET THEM HAVE THEIR STOMACH FULL. Then only we will be justified in asking them questions. .

Excellent ! Hope the present day politicians read this!

Excellent article

I have always wondered why Nehru was made the first PM of India when more deserving persons were there in Congress. Nehru’s favouritism for his close friends have shown the seeds of Nehru dynasty that ruined India for several decades.

Nehru made stupendous contribution to India. We would not have been what we are now without Nehru. But he also made colossal blunders in the realm of external relations. They are many: Some are listed below: (i) He stopped our forces from evicting the Pakistani marauders from J and K when victory was at sight, at the behest of his friend, Lady Mountbatten; If allowed to throw out the marauders totally, Kashmir problem would be non existent today; (ii) He allowed the Chinese PLA to annex Tibet using the hair splitting argument between “suzerainty” and “sovereignty”. Had he taken the western help, who were more than willing at that time, Tibet would be a free country, acting as a “buffer” between India and China – and there would be no challenger in our Northern front, besides permanently cutting down the ambition of China as a Super Power in the area; (iii) Nehru should have exploited the opportunity to enter into the Security Council as a permanent member with veto power when there were signals from the west to that effect – he did not make even a faint attempt in that direction which was a total betrayal of our national interest; (iv) On the other hand, for same strange reasons, he vociferously lobbied for the entry of Communist China into UN and also in the Security Council with Veto power and he succeeded in his attempt – and we are facing the music today (v) Nehru supported the “one China policy” blindly. Had he not supported this , Taiwan would not have been isolated in the comity of world. In synopsis, Nehru was blinded by anti-imperialism, neo-colonialism and capitalistic ideology and he, aided and abetted by V K K Menon, had developed most indefensible fascination for crypto-communist ideology. They brought disaster on this country. We are paying a heavy price for that. a k pattabiraman, Chennai

I still wonder what good things had not happened in India without Nehru. On the other hand without Nehru India could had many more good things that Nehru screwed. In today’s India if a person speaks with the voice of Nehru, he/she is bound to loose election.

This reply of yours is very relevant and deserves to be an independent article on its own!

Wish all Indians ( especially hose past the baby boomers) read/know about the fact s narrted in , bu you.

Thanks!!

Unfortunate for India not listening to Swatantra party, if only Gandhi had supported Rajaji to PM , we would have been in the driving seat in Asia.

This is an extremely interesting article. How come we dont read or discuss much about such a wonderful party? If it were upto me I’d toss both BJP and INC for swatantrata party. They got almost everything right. Free markets, individualism, democracy, aligning with rest of the free world. Ironically it was our democracy itself that killed this party. I think all the centrists in India should form a party and draw their inspiration from this party.

Democracy kills parties that are unfit for democracy. With Swatantrata party there was huge difference between the preachings and the practice. We now know how lofty ideals librandus and Communists talk about and they are the one who would kill democracy on whims and fancies.

BJP and Congress are two sides of the same coin. Both are extreme left wing parties which believe in big government that should do everything from running airlines, banks , temples to passing laws in parliament. The truth is that India needs a party that believes in economic and social freedom. India needs greater participation of individuals and society rather then government diktats.