Formulating the right strategy for industrial development and employment generation is particularly important for India, which is undergoing a demographic transition. The number of youths entering the workforce each year (10–12 million) is equivalent to the entire population of Belgium or half that of Australia. This change in population offers a potential demographic dividend—a great opportunity to boost the country’s growth, provided that the economy can generate productive jobs for these new entrants.

Policy agenda

The importance of policy interventions is often overstated. Economic growth, in most of today’s Western societies, was both endogenous and organic. Public policy came into force to protect and secure private wealth and to ensure its later redistribution. Consequently, perhaps the best government policy would be to not intervene by throwing sand on the wheels of economic activity.

It is unnecessary to dwell on the well-known requirements of investing in infrastructure and easing constraints on land, labor, and capital markets. India’s central and state governments continue to pursue industrial policies to fulfill them. However, these policies typically focus on larger firms, and more attention needs to be paid to supporting smaller firms.

Promote Productive Entrepreneurship

In India, the two most consistent factors that directly correlate to the formality of enterprises—in both the manufacturing and services sectors—are education levels and the quality of local infrastructure. These correlations have been found to be much stronger in India than in the United States.

Despite its laudable aim to promote entrepreneurship, India’s government may be struggling to encourage entrepreneurship development programs, establish incubators and accelerators, and promote industrial clusters. Therefore, a primary takeaway would be to eschew policies that seek to create entrepreneurs or directly promote entrepreneurship. It may be further advisable to limit efforts toward shrinking the informal sector. It could be more productive to create two types of conditions favorable for enterprise creation and growth: physical and enabling. The former involves making improvements to infrastructure, increasing access to credit, providing skilled labor on competitive terms, and so on. The latter involves services that improve the productivity of businesses—by structuring them as quasi-public goods and subsidized by the government—and the enabling of regulatory environments.

Make Starting and Growing Businesses Easier

India is often considered one of the most difficult places to start and run a business. Although its Ease of Doing Business global ranking, produced by the World Bank, rose significantly from 130 in 2016 to 77 in 2018, big hurdles to starting and growing businesses remain.

One of the biggest hurdles that potential enterprises in India face is the complexity of the registration system—all enterprises must register separately with multiple entities of the state and central governments.

One portal that integrates all state and central government departmental registrations into a single workflow application would be the most effective way to ease the conducting of a business.

Further, compliance—especially related to payments and reporting requirements—could be made much simpler. Instead of maintaining physical registers, firms could log in to this single portal and, on entering all the relevant data, receive a report that meets their various legal requirements.

Facilitate Access to Credit

Many informal enterprises are outside the tax system simply because they deliberately operate below the threshold for registration.

MUDRA, which provides loans to microfinance and nonbanking financial institutions for on lending to small entrepreneurs, was established in early 2015. MUDRA is needed to address productivity and working conditions in the informal sector and in informal employment. However, policy interventions without benchmarks, and measurements of achievement against such benchmarks, are incomplete and ineffective. It is vital that beneficiaries of MUDRA loans do not see them as handouts or loans that could be waived, as this would disincentivize borrowers from growing their businesses. Unfortunately, that may be happening. There are reports of high rates of repayment failures in loans extended under the MUDRA scheme.

One condition for MUDRA loans should be that the entrepreneur maintain books of accounts. All MUDRA borrowers should be required to report their employment generation and productivity data, such as output produced per unit of capital and labor employed.

The government should measure the success (or failure) of loans made under MUDRA by the reduction in informal employment, the rise in formal employment, and the extent that firms become medium and large. These objective criteria will help ensure that decisions are apolitical.

Accessing credit is not just a challenge for informal enterprises but also for formal start-ups.

A recent survey found that nearly 40 percent of the annual credit demand of MSMEs, amounting to about 20 trillion rupees, is met through informal channels, where the cost of capital is much higher. Further, 99 per cent of formal financing occurs through banks and nonbanking financial corporations and is primarily nondigital.

The ultimate goal would then be discouraging informal enterprises from adopting low-productivity tactics and methods. In addition to deregulating the environment, enhancing size-based thresholds for businesses to avail of financial and other concessions, and lowering compliance and labor costs, increasing access to affordable credit would complete a policy package directed toward MSMEs.

Improve Tax Policies and Encourage Start-ups in India

Arbitrary Tax Claims

Over the last decade, the government has created well-meaning initiatives to support entrepreneurship, such as Stand-up India and Start-up India. However, one initiative implemented by the tax department in 2012, called the “angel tax,” has nullified other well-meaning initiatives because it treats the premium over the face value of shares subscribed to by investors as income in the hands of start-up businesses.

Extracting the states’ due share of taxes from wrongdoers must be weighed against the cost of hurting and harassing the majority of honest start-ups struggling to stay afloat and succeed.

Inadequate Tax Incentives

While arbitrary tax claims are a big concern, they are offset by other incentives. For instance, the government also gives tax holidays to start-ups for three out of seven years, if their sale turnovers do not exceed 250 million rupees. However, this sales turnover ceiling is too low according to international standards, particularly given the size of the Indian economy and the current exchange rate between the Indian rupee and the U.S. dollar.

The widespread perception that the government is giving away or giving up its tax revenues should be contested. Though it may not seem possible to build a bridge between policy initiatives that (appear to) let go of revenues and future economic growth, the association between the two will become apparent in the data on economic growth, employment growth, and tax revenue growth that will emerge over time.

According to the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business 2019 report, the number of hours spent on paying taxes in Mumbai was estimated at 277.5 hours, a poor comparison to the global average (237 hours), the OECD average (159 hours), and countries like Singapore in particular (49 hours).80 And the number in Mumbai has only been increasing. The number of hours spent in paying taxes was estimated at 214 in the 2018 report, but after more data on GST payments were obtained, this number was revised to 275 hours. With this number going up to 277.5 hours in 2019, PwC— which provided some of the data to the World Bank—made this note on introducing the GST:

In 2017, multiple central and state indirect taxes were merged into one with the introduction of the GST system. The transition, however, led to some administrative, operational and system issues that increased the time to comply. For example, the rules for filing and paying GST and for determining the GST rates were not always clearly communicated, there were issues with the functioning of the online portal and not all rules were synchronized prior to the introduction of the GST.

Considering the number of hours spent in filing taxes and appealing assessments, the hassle of dealing with the bureaucracy has a far higher monetary and morale cost than the actual tax paid.

Incentivize formal employment

According to the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business 2019 report, India’s total taxes and contribution rate (calculated as a percent of profit) was 52.1 percent (versus 55.3 in the 2018 report).

In addition to taxes, labor costs are a formidable barrier that stunts the growth of Indian businesses, particularly in the formal sector. Manish Sabharwal, the chairman of TeamLease Services, a staffing company, wrote that salaries of 15,000 rupees a month end up as only 8,000 rupees after all deductions, from both the employer and employee sides.

These mandatory deductions and the high taxes and contributions squeeze employees, and only some of the employer’s burden is passed on via a net reduction in the employee’s paycheck. But any reforms that dispense with social protections are not only undesirable, but also unlikely to pass muster politically. Solutions to address this issue could range from making these deductions for both sides voluntary to providing a partial public subsidy for some of these contributions.

Subsidize small business productivity enhancement services

To create productive jobs, India’s central and state governments have proposed industrial policies to attract new business investments. However, by their very nature, industrial policies—focused on input subsidies and tax concessions—disproportionately benefit larger and more established businesses. They are also very expensive to implement. Intense lobbying by these beneficiaries only helps to perpetuate more of the same.

Much of the mainstream research on business productivity enhancement support has revolved around the provision of trainings—mainly to groups of entrepreneurs—despite little to no evidence of its efficacy. The problem with training programs is that they are more likely to be employed as an instrument to stoke entrepreneurship than as an effort to address the specific business development challenges faced by entrepreneurs. Further, weak state capacity may inhibit the effective delivery of training programs at scale.

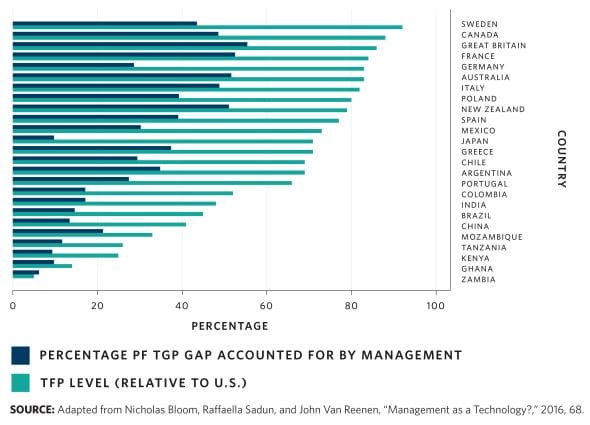

Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen, who lead the World Management Survey, examined management practices from over 11,000 firms in thirty-four countries and found that “differences in management practices account for about 30% of cross-country total factor productivity differences” with the United States (see Figure 1). They also found that firms facing greater competition were more likely to have higher management scores.

Figure1: Total factor productivity gap accounted for by management practices

Business productivity enhancement services could be expanded beyond supporting an individual firm’s specific management services to include conducting market assessment surveys, creating business development and market access strategies, preparing detailed project reports, benchmarking and assuring quality, and assisting with recruitments and procurements. Further, productivity support could come from individuals or consultants, offering guidance to geographically concentrated groups of enterprises, as well as easily customizable, smartphone-based inventory, procurement, and human resource management software. Entrepreneurs could offer these software services commercially through a freemium services model, with a subsidized basic version.

In India, it may be tempting to view business productivity services and agricultural extension services similarly and thereby offer the services through public officials. However, this is unlikely to be effective, as public officials do not possess the required level of expertise and government agencies do not have the same profit motive as private providers—a motive that leads the latter to constantly upgrade their services and expertise.

Let Go of the Anti-big Bias

The implementation of any reform is likely to remain suboptimal without a paradigm shift in the way the Indian state views and engages with the private sector. Instead of taking an adversarial and regulatory-oriented approach, it needs to highlight partnership and facilitation. The anti-big bias reflected in the government and public policy is a problem that has yet to be tackled effectively.

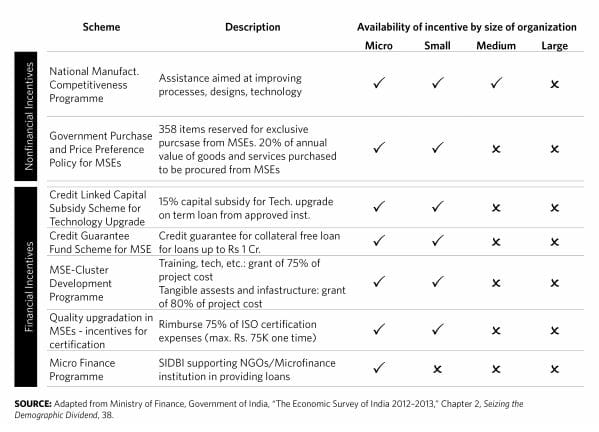

The Economic Survey of India 2012–2013 contains a rigorous discussion on India’s demographic dividend and how it could be harnessed to benefit the country. However, this will only be feasible if youth have the right education and skills and are either entrepreneurial or earn their living through formal employment. Though jobs are typically created as firms grow in size, the productivity of thirty-five-year-old firms in India have merely doubled, while their headcounts have fallen by a fourth. Since this is neither normal nor healthy, economists and policymakers have attempted to examine the causes of these issues. They have found that labor laws, rules and regulations, and the cost of hiring and maintaining permanent workers in every sector matter and often encourage or condemn firms to remain small in size (see Table 1).

Table 1: Government incentives that disincentivise growth

The survey notes, Schemes and interventions based on tightly defined classifications create an incentive structure that might prevent firms from growing. Service tax exemptions for firms with less than Rs 10 lakh [1 million rupees] revenue and exemption from central excise duty for firms with an annual turnover of less than Rs 1.5 crore [15 million rupees] are examples of these schemes.

In 2017, the newly constituted National Institution for Transforming India Aayog, a government established policy think tank, developed this theme in its latest enterprise survey on the ease of doing business in India. The survey found that firms with 100 or more employees took significantly longer to get necessary approvals, confronted more regulatory obstacles, and faced higher compliance costs than smaller firms. For firms employing more than ten people, tax regulations and environmental clearances were bigger obstacles, which made it harder for them to grow in size.

India’s smaller factory sizes are also a big deterrent, particularly in fulfilling export orders. A typical textile factory in India employs 150 people, whereas a factory in Bangladesh has 600 people. In 2017, the Textile Commissioner of India stated that India’s textile industry would grow from its current size of $150 billion to $250 billion (about 10.5 trillion to 17.5 trillion rupees) in two years. It is pertinent to note here that only two textile firms, Alok Industries and Arvind, are large in size, as the former had a turnover of a little under $2 billion (140 billion rupees) and the latter had a turnover of around $800 million (56 billion rupees) in the 2015–2016 financial year. This is in stark contrast to the IT industry, where billion dollar firms are numerous.

Gursharan Bhue, Nagpurnanand Prabhala, and Prasanna Tantri point out that firms are willing to forgo growth in order to retain their access to finances.110 That is, when certain easier financing access is provided to firms below a certain threshold (say, SME firms), they prefer to forgo growth opportunities that would allow them to cross this threshold: “firms that near the threshold for qualification slow down their investments in plant and machinery, other capital expenditure” and experience slower growth in manufacturing activity and output. 111 The authors also point out that when banks are put under pressure to lend to micro, small, and medium enterprises, they fear the fallout of not meeting those lending targets and consequently encourage their borrowers to stay small.

As a potential solution to these issues, Bhue, Prabhala, and Tantri also suggest removing the conditions that make directed lending to small enterprises necessary. That is, if informational, administrative, and monitoring costs are lowered, banks might be willing to lend to small enterprises and not feel pressured to prevent their growth. However, another potential solution may be to slowly phase these firms out of this financing system so that they do not conspire to remain small and forgo opportunities to grow.

Conclusion

International evidence and the current state of affairs in India with regard to the size of commercial businesses (average number of employees) suggest that government policies on MSMEs must become more nuanced. These policies must take into account the central role that new and smaller enterprises, established by educated entrepreneurs, play in productive job creation.

Informal micro enterprises, and single-person enterprises run by those lacking in formal education, should be termed as subsistence enterprises. The government would then be obligated to support them with basic public goods, including education, and a robust social safety net. Educating the next generation is critical to breaking the iron grip of poverty and pulling single-person enterprises out of survival mode. However, support for these subsistence enterprises should be provided under anti-poverty measures and not under economic development (much less under productive job-creating measures).

To create these conditions and generate employment and economic development, policy interventions have to change. In general, the government’s perception of entrepreneurship as a viable and sustainable solution to the lack of employment is well founded. International evidence is supportive of this—start-ups and young firms create more jobs, regardless of their size, and educated entrepreneurs have a far higher probability of success in starting and growing formal businesses. Therefore, public policy to support entrepreneurship and MSMEs should target these entrepreneurs. However, any government support should be made contingent on the enterprise’s progress in creating jobs and productive growth, thereby encouraging more dynamic entrepreneurship.

India’s job creation strategy should focus on three efforts. First, it should promote the creation of formal businesses by easing the barriers to business incorporation. Second, it should support new businesses during their initial, vulnerable years with policies that help them find their feet and expand. Third, it should include reviewing and modifying policy measures that may impede small and medium businesses from scaling up.

Venkatraman Anantha Nageswaran is the dean of the IFMR Graduate School of Business (Krea University, Tamil Nadu).

Gulzar Natarajan joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1999 and is currently senior

managing director at the Global Innovation Fund.

This is an edited excerpt from the authors’ working paper, India’s Quest for Jobs: A Policy Agenda, published by Carnegie India. Read the full paper here.

It seems that no one in the government is worried about the unemployment & growing unrest in youth.The economy has slowed down,the GDP ratio is declining,the development ratio as per world bank has totally decreased. Even though no one agree it. Insead of that they are the best lawyers in providing reasons with emotional firecrackers for last 3 months in with 370 & Kashmir issue.