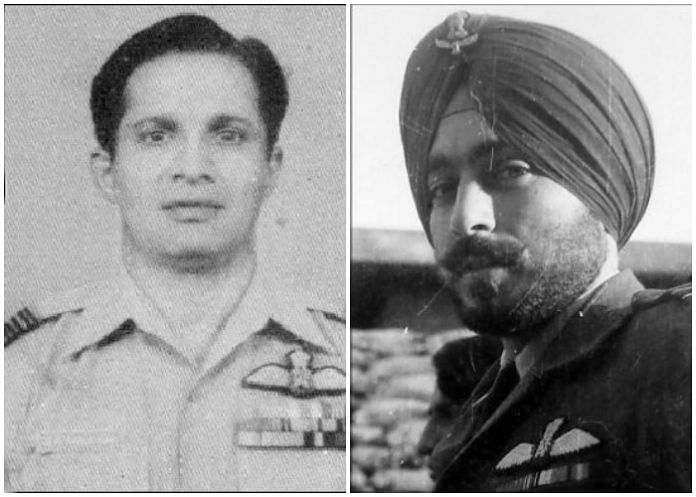

In the first part of this ‘Walk the Talk’, Wing Commander M.S. Grewal and Group Captain Dilip Parulkar told Shekhar Gupta how they planned their escape from the PoW camp near Rawalpindi in 1971.

In the second one here, their adventures in brief freedom. And how they were caught.

SG: When you started planning the escape, what was the first thing you did? I believe Dilip sir here wanted to kidnap a Pakistani soldier.

Parulkar: That was the first thought that came to me. Whenever we went to the toilet at night (while in custody), one very sleepy corporal with a side holster and revolver would come with us. I remember his name, Corporal Mahfuz Khan. He was a Pathan from the NWFP (North-West Frontier Province), very dopey. I thought I could easily capture him. I was in my early 20s, I thought I could hold his revolver against his head, holding him hostage. This romantic idea came to me because of one aeroplane that had been commandeered by an Italian lover in the US. He had got the pilot to fly back all the way to Europe. But those are American values and Italian values.

SG: Moreover, you were trading a poor corporal for a flight lieutenant!

Parulkar: In fact, when I thought over it calmly, I thought that in our country, they would shoot him before they shoot me for allowing this to happen (laughs). So I gave up that idea.

SG: When did you start on the wall?

Grewal: See, we knew from our observations, from the bathroom where you could pull yourself up into a little ventilator, that there was an unprotected area behind our room. It was a biggish room and there was a little corridor used by the Pakistanis to move from a building to our area. That particular building was a recruiting and information centre for the Pakistan Air Force and it was completely unprotected at evening and night, with one chowkidar sleeping outside. We knew that if we could go through the wall, we would be in that building. It was Dilip’s room to start with.

SG: Were you able to scrape out the window?

Grewal: No, the window idea was before that. He (Dilip) was trying the window by himself. The window was also in the same room, looking on to the same corridor.

Parulkar: The window was located such a way that it could be seen only from a very specific, small, zone. Also, it was very old.

Grewal: It was half-gone, the frame was shaking.

Parulkar: So that is what gave me the idea. I did work on it up to the point where one push would have sent it out. And that required the cover of bad weather.

Grewal: Thereafter, we got down to the other plan, where we finally made it.

Parulkar: That was after Gary (Grewal) joined us.

Grewal: We had the wall worked out, we had the bed placed there, the bed covered with blankets, manoeuvred from here and there.

“The masala in between the bricks was not very strong”

SG: How did you dig the hole into the wall?

Grewal: It was an 18-inch-thick wall, you know, how they put bricks one after another, and mortar on the sides. We knew we had to scrape off the mortar inside. The mortar outside, we did not know about. But in between the bricks—what we call masala—it was not very strong.

SG: What did you use to scrape it?

Grewal: We had a knife, a fork. And, in there, we were allowed to call a little boy to get us soft drinks like Coke or Pepsi. They would not remove the lid because it spilled. Have you seen an automobile engine valve? They had sharpened it and they would put the valve on top (of the bottle), bang it in and put a straw in. I took this valve from him.

Parulkar: We also had scissors, we had all grown a beard and we used it for trimming.

Grewal: With these three-four things, we could scrape the mortar in between the bricks.

We would get down to work at night, Dilip and I. I would do it for half an hour, then I would get out, then he would spend an hour there, then I would get back. We went on till 12.30 or 1 at night, while (V.S.) Chati and Harish Sinhji (the third person to escape with Grewal and Parulkar) kept watch.

SG: Nobody heard anything suspicious?

Grewal: No, the guards were far away, and they were patrolling. And scraping was a slow process. The mortar that came out, we would put it in Red Cross boxes and stack them up right in front of them during the day. They could see them, but nobody opened to see what was inside the boxes. And we would clean the (cleared hole) and put the bricks back, and then again start. This process went on for more than a month.

SG: What was the inspiration? I believe The Great Escape, Steve McQueen?

Grewal: Oh yes, we had seen all those movies, read all those books.

SG: Papillon?

Parulkar: I had read Papillon just prior to…

Grewal: Have you heard about The One That Got Away, by (Franz) von Werra?

“This is breaking like a biscuit”

SG: So what happened when you three got out? Chati stayed back.

Grewal: Once the hole was ready, the three of us were prepared. We told everybody we will be going. Before that, two of our attempts had failed.

Parulkar: Gary, because of his father’s experience with criminals in Amritsar, had this idea that we can go through this all in one night. That is what burglars used to do in Amritsar.

But we found this plaster to be a very huge obstacle. What we had to do is make a groove right along the periphery of that hole. We had made a size through which we could crawl easily. And we were making a groove right around the boundary of it. Gary was the last person to work on that. When he finally broke pieces of it, he said, ‘Dilip, ye to biskut ki tarah toot raha hai (this is breaking like a biscuit)’ (laughs).

SG: And then you smelled freedom.

Grewal: It had just started raining, drizzling.

Parulkar: The bad weather that we were hoping for all along happened at that very time. Providence was on our side.

SG: I believe you walked out when a movie show had ended, there was a lot of crowd.

Grewal: Yes, we presumed a movie show had ended because there were rickshaws, tongas, shouting, the typical Indian scene. We were like anybody else on the road.

“There was a gap in our intelligence, it was a major gap”

SG: And then what happens?

Grewal: We come to a place where Peshawar University is on our right. At this university, there are a lot of people, and we don’t know whether to proceed or stop. Dilip suggests, let’s hide under a culvert. There’s a railway line on the left.

Parulkar: Which we had studied on the map, that there is a railway line which goes on the left. That was part of the plan, to follow the railway line. And that would go past Landi Kotal up to Landi Khana. According to the map, Landi Khana was the last halt in that district. That was a gap in our intelligence, it was a major gap. It was there in the British days, but no more.

Grewal: You see, Landi Khana had vanished. So finally when we reached there, after one bus ride and then another bus ride…

SG: You were searching for a place that didn’t exist anymore.

Grewal: Right. It was a train station in British times.

Grewal: We could have told a taxi fellow that we want to go to Torkham. But we thought if we tell him Torkham, he’ll say, ‘Oh, they want to cross the border’. So we said we want to go to see Landi Khana, and we’re going back from there. But there was no Landi Khana.

SG: Then you got caught. The tehsildar’s clerk, or someone, got suspicious.

Grewal: Steno or clerk, someone. We are standing there, the three of us. There’s a tea shop, and we’re talking to the taxi guys, and we are negotiating just for the sake of negotiating, to bring down the price.

SG: So it doesn’t look like you are throwing money.

Parulkar: That’s right.

Grewal: We are just being natural. But this guy is standing there, the road is not very wide. He comes across and says, ‘Kaun ho, kahan jana hai (Who are you, where are you going?)’. We said we’ve come from Lahore, we are going to Landi Khana. He said there is no Landi Khana. In the meantime, Dilip had gone and bought caps, we had put the caps on our heads and we had finished the tea. People started gathering.

Parulkar: We had decided money was no issue, let’s go. Because we had money.

“We had apricots, we had chocolates, we had condensed milk tins”

SG: You were getting your PoW allowance, Rs 57 a month, a princely figure then, in addition to your salary in India.

Parulkar: Which I saved very carefully and, on the last two days of the month, the group used to get after me, ‘Dilip, tu is mahine to nahin jaa raha yaar (you are not going this month, no), let’s buy khubani, apricots’.

Grewal: We had apricots, we had chocolates, we had condensed milk tins.

Parulkar: And that was part of our escape kit.

SG: So then you were caught.

Grewal: The tehsildar called some people, they took us to a so-called prison and locked us up. They searched us. We had PoW ID cards. They were in English. The people there, none of them could read English. So, one of them takes these three cards, he goes to the tehsildar. The tehsildar comes back with these cards, and he’s probably figured out what they are. Now, we are locked inside this cell, and he’s shouting at us, ‘Tum Hindu ho, tum ye ho, tum wo ho’. In the meantime, he’s told the political agent, Mr. Burki. Mr. Burki says, bring them over. So they handcuff us and walk us through the village. People are looking at us, following us, to Mr. Burki’s office. Poor chap, it was a holiday, he came from home to meet us. First thing he did was to have our handcuffs removed, made us sit down, made us comfortable, tea came, and then, of course…

SG: I believe Dilip sir, you planned one more escape trick. How did that happen?

Parulkar: I was the prime mover in this whole process. I felt a sense of responsibility, because this was also something which I was accused of by the people who didn’t want us to go.

SG: That you were overdoing it.

Parulkar: Yes, so much so that at one point, they said, ‘Look here, if anything happens to either of these two guys, you are responsible, Dilip. Be careful’. So, my take on that was, ‘I am not responsible for that. Anybody who doesn’t want to come is at liberty — it’s a free country — to say no. But I am going. Anybody who wants to, can come with me’. Now, because of that, they were with me. Something I learned only at the National Defence Academy, it’s there in golden letters in the library — first comes the safety, welfare and honour of your country, second comes the safety, honour and welfare of the men you command, and your own safety comes last. So, although I was not their commander, I was their leader. So it was up to me. They were in this soup because of me. So I had to get them out of it also.

SG: Invent something.

Parulkar: We already knew that Usman Hamid had relinquished charge of the PoW camp and had gone as ADC to the chief.

SG: That’s very funny because one of your PoW colleagues, D.S. Jafa, had been ADC to our air chief, Air Chief Marshal P.C. Lal.

“Told tehsildar we are airmen from the Pakistan Air Force station in Lahore”

Parulkar: So, Usman Hamid had gone from being our camp commander to Pak air chief Zafar Chaudhry’s staff. We knew this because after taking over as his ADC, he brought Zafar Chaudhry to the camp, and he visited us. We met him. He was a gentleman, he never threw his weight around. He never made us look small, which was a big change when the new camp commander took over. So, anyway, with this knowledge, the tehsildar was questioning us as to who we were. He had not yet found those identity cards, which we had hidden in our waistband pockets. So I told the tehsildar we are airmen from the Pakistan Air Force station in Lahore, and that I wanted to talk to the ADC to the chief of air staff. We told him we are on 10 days’ casual leave and we are going up to Landi Khana as tourists, just trekking, sightseeing. He said no, we are going to lock you up. And after 10 days, when they start looking for you, we’ll release you, and then you can go back… I knew in 10 days there would only be corpses going back. So I was not going to take that chance.

After haggling with him for a while, I even made a show and a sham of getting him fired. By that time, we had learnt enough of their language to talk to them. I said, ‘Janaab, main aapko bata raha hoon main Air Force Station, Lahore, ka airman hoon, parachute section mein kaam karta hoon main, aur is watan ke liye main khoon bahata hoon. Aap mujhse aise, is tareeqe se, bartaav kar rahe hain! Main aap se kisi chhote-mote aadmi se baat karane ke liye nahin keh raha hoon. ADC to chief of staff se baat karna chah raha hoon. Aur aap nahin bol rahe hain. Aap ki khairiyat nahin hai (Mister, I’m telling you I’m an airman of Air Force Station, Lahore, I work in the parachute section, and I spill my blood for this country. And you are treating me like this! I’m not telling you to put me through to some lowly official. I want to talk to the ADC to the chief of staff. And you’re saying no. You’ve had it).

SG: So he put you through.

Parulkar: Yes, immediately. Peshawar is not very far from where we were.

SG: The PAF Headquarters was in Peshawar.

Parulkar: And it was their independence day. He got through in minutes. And this conversation started, ‘Sir, Philip Peters is here, with Ali Ameer (Grewal)’.

SG: Those were your assumed names.

Parulkar: Philip Peters was chosen by me because it rhymes with Dilip.

SG: Pretending to be an Anglo-Pakistani.

Grewal: Plus, we had to remember our assumed names. I had a course mate named Ali Ameer.

Parulkar: I had a classmate called Philip Peters.

SG: So you spoke with Usman Hamid. What did you say?

Parulkar: I said, ‘Sir, Philip Peters here. Do you know Dilip from the camp?’

SG: So, you first said Philip, then slipped in Dilip.

Parulkar: ‘We had taken some leave from the camp, sir’, I said. ‘And besides me, Ali Ameer and John Doe are both here. We were on our way to Landi Khana, sir, as tourists, and they’ve suddenly stopped us for no reason.’

Grewal: ‘And they are not letting us go’ (laughs).

Parulkar: I told him, ‘Sir, you know me, they cannot hold us’.

Grewal: He caught on.

SG: How did he respond to you?

Parulkar: He was aghast. He said, ‘Dilip, Dilip, what are you doing there in Landi Kotal?’. I said ‘Sir, we just took a little casual leave, and that’s how we are here, and look at this…’. He said, ‘Give the phone to the tehsildar’. I gave him the phone. He very calmly told him, ‘Ye hamare aadmi hain (These are our men)’.

Grewal: He immediately caught on. Till then, they had no information from their sources. This was the first time he was hearing this. But he was clever enough to know that something had happened.

Parulkar: There was no way the three of us should be in Landi Kotal.

SG: So actually he saved your lives.

Parulkar: That was the plan. I put the jurisdiction at such a high level that the local fellow has no jurisdiction.

SG: It also tells you that wars take place, but there are also decent people on both sides, and that decent people also go to war. That’s the reason I feel blessed we’ve had this conversation, of friendship, and mutual soldier chivalry.

(Parulkar now lives in retirement in Pune, having tried his hand as a developer-builder. Grewal retired to farming in Terai. Harish Sinhji retired and settled in Bengaluru and passed away in 1999 from multi-organ failure. Canadian journalist Faith Johnston, an Air Force wife, documented their story in her Four Miles To Freedom [Random House India, 2013]. Regrettably, the three weren’t given any gallantry award for this incredible audacity and ingenuity.)

Dilip

Would like to get in touch with you.

Anil.dabir@gmail.com

Shobhaa De once asked Dhirubhai Ambani which quality a young person should have to get ahead in life. Guts, he replied simply.

Wonderful. Thoroughly enjoyed it.