As India enters into an extended period of lockdown to deal with Covid-19, a pivotal battleground in India’s struggle to contain the pandemic is still in our blind spot. The unique characteristics of slums — a dense urban microcosm of residents and activities minus the superior ‘urban’ infrastructure and services — render them especially vulnerable, as seen from the Cholera outbreak in Victorian London to the African Ebola outbreak of 2015. According to the UN-Habitat, the coronavirus pandemic will hit informal settlements and slums the hardest as these are perpetually constrained for space and basic services.

Also Read: Dharavi is a ticking bomb in the Covid-19 challenge, nothing being rolled out will be enough

Sanitation in slums

In 2014, the World Bank estimated that around 24 per cent of India’s urban population, which means about a hundred million people, lives in slums.

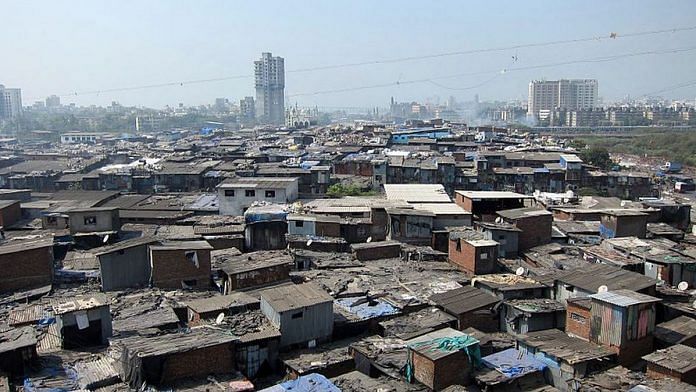

India’s average urban population density of 3977 people per square kilometer (PSK), comparable to Wuhan’s local population density of 44,00 PSK, hikes upwards of 20,000 PSK – twice that of New York City — in Mumbai and Kolkata.

Within cities, the densities of slums range from an average slum density of 6,200 PSK in Bhubaneshwar to 2,77,136 PSK in Dharavi, Mumbai and 125,000 PSK in Rasalpoora, Hyderabad.

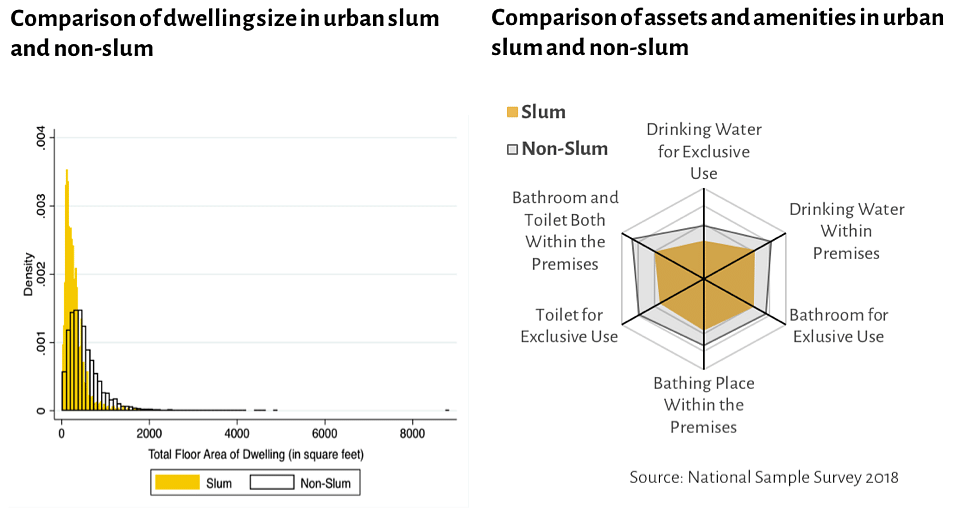

According to the National Sample Survey (NSS), 2018, 50 per cent of slum households reside in houses less than 230 square feet in size.

Access to safe water and sanitation is a critical safeguard against infectious diseases, but 60 per cent of the residents rely on a shared source of water, and nearly 40 per cent of slum residents do not have access to both a toilet and a bathroom within their house. Water and sanitation are accessed through precious shared infrastructure, provisioned at a frequency significantly lower than the prescribed norm. This will have two-fold consequences for people living in slums during the Covid-19 crisis.

First, it restricts the households’ ability to practice frequent and proper handwashing. As recent studies of slums in Kolkata, Hyderabad and Mumbai have shown, per capita water supply can be as low as 20 litres per capita per day (LPCD) in comparison with the urban standard of 135 LPCD.

Furthermore, more than 78 per cent of community toilets in Mumbai’s slums lack a reliable supply of water, pointing out that public infrastructure is ill-equipped to cater to hygiene needs. The primary fail-safe against Covid-19 finds slum residents at a disadvantage owing to water insecurities that inhibit frequent hand washing.

Second, congestion in housing and accessing water and sanitation services makes social distancing in Indian slums a completely different exercise compared to that of other significantly Covid-19 affected countries, our middle class, or as advocated by our leaders during the lockdown. A recent study in Delhi slums showed that owing to high densities and congested services, a slum resident makes 50 per cent more contact with other individuals compared to a non-slum resident — making social distancing taxing and less effective and leading to an infection rate among slum residents 44 per cent higher than non-slum residents.

The poor level of water and sanitation services in slums engenders higher health risks and the limitations of these settlements to exercise Covid-19 hygiene and social distancing measures necessitates that the state initiates pre-emptive emergency actions.

Also Read: India’s urban and rural poor expect different things from their local govts, and why it matters

Nationwide impact

The Epidemics Diseases Act, 1897, (EDA) the colonial-era law enacted to respond to Bombay’s bubonic plague, is India’s primary legal framework for dealing with epidemics. Unsurprisingly, the archaic Act has faced criticism for situating isolation and quarantine as its central strategy while not reckoning with contemporary concerns of urban density, newer transmission routes, or scientific and technological breakthroughs like vaccines and surveillance.

In compensating for the deficiencies of the EDA, the Narendra Modi government has evoked the Disaster Management Act, 2005, (DMA) that unlike the former provides extensive guidance on institutional arrangements and coordination mechanisms for the national, state, district, and local governments. While states and the central government are using only a few sections of the DMA, a fuller use of the Act could allow for better planning and proactive measures beyond ‘relief’, ‘recovery’, and ‘resilience’ for disaster-affected areas.

The DMA also provides for pre-emptive action to any ‘threatening disaster situation’, and the Act empowers the State Disaster Management Authority to enact measures including the provision of “shelter, food, drinking water, essential provisions, etc.”.

Given that a delay in addressing water and sanitation concerns in slums will have citywide and nationwide impact, a more expansive interpretation and use of the Disaster Management Act for the management of the pandemic are needed to deal with the Covid-19 crisis more proactively and compassionately in high-density vulnerable settlements like slums.

Shubhagato Dasgupta is a senior fellow, Anindita Mukherjee is a senior researcher, and Neha Agarwal is a research associate at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. Views are personal.

This article is a part of ThePrint-CPR series based on Scaling City Institutions for India’s (SCI-FI) research on water and sanitation. Read all the articles in the series here.

Build separate toilet for each slum in Mumbai, to stop the spread of Corona virus. At present same toilet is used by multiple families. Which is spreading the corona virus.

Its easy to point fingers. This is the favourite passtime of every Indian, to point fingers. Mumbai is not a small city, oh sorry Mumbai is a small city, but what about the population???Can it support such big population. It just can’t, and it is probably in these times that it shows that we have messed up a beautiful city like Mumbai with over population. Mumbai total sq km is not even half of that of Delhi with an equivalent population. So try and write articles that make some logical sense. None of the governments in any part of the country could have control this. Also as a citizen of the state of Maharashtra this government has done a remarkable job ( though i am not a hardcore supporter of this government). So stop critisizing without any logic.

That’s because we have a population explosion. Support population control measures through law and strict implementation.