Kerala: Bindu Sampath has been a certified makeup artist for 31 years; her residence in Trivandrum serving as her own little beauty parlour — ‘Binduzz’.

But in the last five years, she has stopped receiving the kind of clientele she earlier would. Sampath reckons it has something to do with how local residents perceive her as the “terrorist’s mother” and her home as a “terror training centre”.

Sampath, 54, is the mother of Nimisha — one of the 21-odd youth from Kerala who fled to Afghanistan, between the 2016 and 2018, to join the terror outfit ISIS.

“They expect me to look miserable and broken all the time. But if I break down, who will fight for my daughter? Every breath of mine today is for my daughter,” says Sampath, having just walked out of her bedroom wearing a pink and white suit, while sporting a striking red bindi and sindoor.

But it doesn’t take long for her brave front to collapse into a bundle of tears, as she reminisces about her daughter.

“My son, Nimisha and I used to eat from one plate when they were little. She used to alter my clothes to her size and wear them because she said she wants her clothes to smell like me. I can’t give up on her now that she is in trouble,” she tells ThePrint, as she looks at the family’s old photographs.

During the course of the past five years, Bindu has looked at various ways to bring her daughter back, especially after news broke in 2019 that Nimisha’s husband was among the many killed in a drone attack, and that the 31-year-old Nimisha and the remaining of those who had fled from Kerala were still alive, and had surrendered to Afghan forces and were imprisoned in Kabul.

Last month, there appeared to be a window of hope.

When the Taliban took over Afghanistan in the middle of August, they broke open various jails in Kabul, letting out the prisoners — Nimisha (Fatima) was reportedly one of them.

“It was a ray of hope, I thought my daughter would finally come back, I was delighted,” Sampath said.

But with weeks having passed since her release, Nimisha’s return seems unlikely, as does that of all the others from Kerala who had gone to join ISIS.

Indian officials have told ThePrint that four Indian widows, including Nimisha, will not be returning to the country anytime soon.

According to official sources, India was talking to the former Afghan government, albeit slowly between the NIA on the Indian side and the National Directorate of Security (NDS) of Afghanistan. But now there is uncertainty with the Taliban having taken over.

According to sources in the Ministry of Home Affairs, no decision has yet been taken on the return of the men and women.

“There is nothing that has been decided on this as of date. After some of the people, including women, surrendered in Afghanistan, they were jailed and there were talks of their deportation,” a source said. “Nothing, however, was concrete. But now since all of them are out, and must have gone into hiding, the chances have become bleak.”

A second source in the security establishment also said that the central agencies were not “very comfortable with their return”.

“They are highly radicalised individuals and it will be a very big risk to let them return to India, hence the reluctance,” the source said. “Some people may turn approvers, but it is too big a risk. Most people who may return and are arrested here will get bail after six months and will be free to roam around here. All these risks are to be taken into consideration before making any decision.”

ThePrint visited the residences of multiple couples who had fled to Afghanistan in the last few years to join ISIS, and spoke to their family members about what they perceive led to their gradual “radicalisation” and whether or not like Sampath, they too want their children to return home — and at what cost.

A family in turmoil

Of Hindu-Nair background, Nimisha’s family is among the 10-odd that are trustees of the famous Attukal temple — a stone’s throw from their home. Nimisha’s brother is now a major in the Indian Army.

Nimisha was a student of dentistry at Century College in Kerala’s Kasargod district when she converted to Islam and changed her name to Fatima Isa in 2016.

She gave up her course, about three months before getting her degree, as she returned home to inform her family of her decision. She then married Bexen Vincent, who had converted to Islam from Christianity.

Sampath says she never understood Nimisha alias Fatima’s decision, but decided to support her nonetheless as all she wanted was to “see her daughter happy and settled”.

But then a few months later, in 2017, her daughter told her via a telegram that she is in Afghanistan. The two kept in touch for some time, before they lost all connection.

On Sampath’s walls are framed pictures of her granddaughter — Ummu Kulsu — who would now be five years old. “I have never met her, but she is my grandchild, I love her. She deserves to be at her home, safe,” she says.

Since Nimisha left, Sampath has been tirelessly working to try and bring her back.

In the last five years, Sampath says, she has written to the prime minister, the President, various ministers in Kerala government, the women’s commission, child rights’ groups, and even filed petitions in the Kerala High Court requesting that she be brought back to India — but to no avail.

Now with nearly a month having passed since Nimisha’s release, all hopes that she would make it back have also dwindled.

“At least when she was in prison, I knew she was getting food,” Sampath says. “But now I don’t even know if she is alive or dead. If she is brought back, I know she might be imprisoned, but at least she will be tried as per Indian law.”

Nimisha is among at least four women who landed up in Afghanistan from Kerala. In their interrogation by Indian officials in Afghanistan, videos of which were published by strategic affairs website StratNews Global in March 2020, the women can be heard defending their decision.

“I don’t want to be in Daesh; I don’t have the philosophy of Daesh; I just wanted (to live under) Sharia,” Nimisha can be seen saying.

Asked if she would want to go back to India, Nimisha says: “India is my place, if they take me, if they don’t put me in jail, I will go… if it’s in my qadr (destiny), I will meet my mother again.”

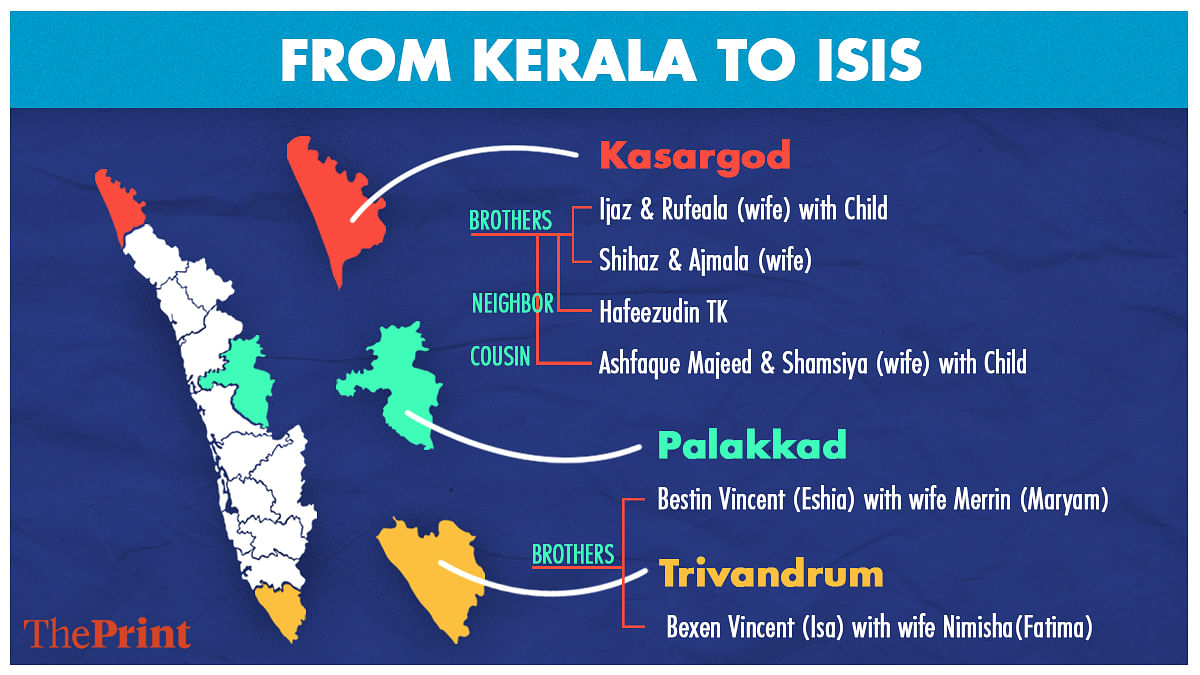

Nimisha’s husband, Bexen, had converted from Christianity to Islam along with his brother Bestin, and the latter’s wife Merrin Jacob alias Mariyam. The brothers hailed from Palakkad and the two couples had fled to Afghanistan together. According to official sources, most of the families travelled first to Iran, and then crossed the border into Afghanistan by road.

A majority of those who left were allegedly “brainwashed” in Kasargod, Kerala’s northernmost district.

In fact, reports had said that one of the terrorists, Mohsin, who stormed a gurdwara in Kabul on 25 March 2020, an attack which left 25 Sikh worshipers dead, hailed from Kasargod. Mohsin had left a few years ago to join ISIS.

Of the others, Ijaz and Shihaz, brothers from Kasargod’s Padanna village, fled to Afghanistan along with their wives in 2016.

Their neighbor, Hafeezudin T.K, and their cousin Ashfaque Majeed were also part of the group; Majeed was accompanied by his wife and child.

Most of those who fled belong to well-to-do families, and were studying to become working professionals — from doctors to businessmen.

No ‘haram’ photographs & loan interest: Road to ‘radicalisation’

At Padanna in Kasargod, everyone knows the home of Abdul Majeed — father of Ashfaque who left for Afghanistan with his wife Shamsiya and one-year-old child in 2016.

But the Majeed residence isn’t known only because of the notoriety brought by their son, but more so because Abdul is known to be a “generous and kind member of the society”.

“Despite everything that happened, the people here stood by us, because our father has an excellent reputation,” Anisha Ajnas, Ashfaque’s sister-in-law told ThePrint. “He is always doing charity work, even people from temples come to him for donations and he happily contributes.”

Abdul runs a hotel business based out of Mumbai, and his hope was that his sons would join in. But Ashfaque, who was pursuing B.Com from a college in Mumbai left it midway, as his “heart wasn’t in it anymore”.

The family thinks Ashfaque’s “radicalisation” had begun around two years before he fled to Afghanistan. For instance, they say when Ashfaque was getting married in late 2014, he refused to have any photographs of the wedding clicked, saying that it would be “unIslamic”.

Ashfaque, a 24-year-old then, also strongly objected to having a lavish wedding, as over-expenditure in weddings is haram or forbidden according to Islam.

“We thought he was only becoming more religious, but we didn’t have any clue of what was happening behind closed doors. He would mostly keep to himself,” Anisha says. “They went by their choice, so we can’t do much. If they come back, we know they will be punished according to Indian law.”

A similar story is cited by the relatives of Ijaz and Shihaz — Ashfaque’s cousins.

A relative, who did not want to be named, told ThePrint that one time Ijaz’s son fell sick, and his father Abdul Rahman offered to take him to the hospital, but Ijaz refused as the car was bought off a loan, which involves paying interests, and interests are considered haram. This had come as a shock to the family given that Ijaz was himself a qualified doctor.

Almost everyone in Kasargod points towards a certain Abdul Rashid as being the “mastermind” who “influenced” the other men involved. Rashid and his wife Sonia Sebastian, who is also a convert, were among those who left for Afghanistan in 2016. Rashid, however, died in one of the attacks subsequently.

In August, Sonia’s father V.J. Sebastian Francis moved the Supreme Court calling for the extradition of Sonia and her now seven-year-old daughter.

In the video interrogation from 2020, Sonia (who had changed her name to Ayisha), can be seen talking about how she and her husband came to Afghanistan to “live under the Caliphate” but that “things were not up to expectations”.

“We came here expecting an Islamic life; to live under Islamic law. But many things were not up to our expectations like the Salat (prayer) in the masjid,” she says in the video.

“I want to return to India, to cut off from everything that has happened, and live with my husband’s family,” she adds.

She further says that “only sadists would be motivated” by the ISIS’ killings but that her motivation to join them was to “live an Islamic life”.

We stand for co-existence and secularism: Kerala’s Salafists

A majority of those who left from Kerala to join ISIS ascribed to a version of the ‘Salafi’ ideology — a reformist movement within Sunni Islam.

The Salafi movement’s origin in Kerala can be traced back to 1920, when it was seen as a progressive force, says Ashraf Kadakkal, professor of Islamic History and West Asia in Kerala University.

“At that point, the Salafi movement in Kerala emphasised on education, the need to give up superstition, among other things,” he told ThePrint. “But gradually there were many rifts and divisions among Salafi scholars, with some adopting a more literal interpretation of religious texts.

“There now has been a younger generation of Salafists, who got disillusioned with all this infighting and cut off from the traditional Salafi movement and chose to self-study. They would rely entirely on online sources for this self-study, not turning to scholars for better understanding,” he added. “In fact, they don’t consider the traditional Salafists as good Muslims anymore, just like a majority of those that ISIS targets are also Muslims who they feel have deviated.”

Kadakkal says that ISIS’ online propaganda and outreach is largely to blame for luring the disillusioned generation of Salafists in Kerala.

“These were all mostly harmless, calm people. Their driving force to join seems to be their desire to live in an Islamic world, something that they didn’t find in Kerala,” he says.

Kadakkal, however, warns against the usage of the term ‘love jihad’ — coined by Right-wing groups to suggest a conspiracy of Muslim men brainwashing non-Muslim women into conversion.

ThePrint had earlier reported how a section of Christians in Kerala, particularly the clergy of the Syro-Malabar Church, had begun issuing statements warning their followers “against love-jihad”.

“If you listen to all the non-Muslims involved, they all seem entirely convinced by the ideology, and are well-versed in whatever version of Islam they ascribe to,” Kadakkal says. “They didn’t convert for love or marriage. So this cannot be termed brainwashing or love-jihad.”

Kerala’s Calicut or Kozhikode district is where the pan-Kerala famous Salafi organisation, the ‘Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen’, is headquartered.

Its vice-president Hussain Madavoor told ThePrint that the work the body does in Kerala has nothing to do with the ideology of those who join terror groups.

“We run several schools across Kerala — all of them are secular, and co-educational. We have an equal number of Hindus and Muslims enrolling in our schools, and an equal number of girls and boys. We teach regular subjects: Science, English, Maths, Malayalam,” Madavoor said.

“The students can take an optional language subject and they can choose between Arabic, Urdu and Sanskrit. Our emphasis throughout has been on communal and social harmony.”

He also said he detests how ‘Salafism’ has been given a bad name by those who claim to ascribe to the ideology and then join terror outfits.

“The term ‘Salaf’ means the first generations of Muslims, that means the first followers of Prophet Muhammad. Anyone can do any misdeed and claim to be a Salafi, but that’s not correct,” he added. “We stand for secularism and co-existence. That is an important aspect of Islam.”

‘20-odd people in 26 per cent Muslims not a high figure’

The NIA had filed a charge sheet in 2017 after the 21 men and women from Kerala had left to travel to Afghanistan to join ISIS.

A senior official in the Kerala Police told ThePrint that the figure continues to be “a little over 20” since then.

“Many of those who went have died. Of the ones who are alive, the figure is a little over 20,” the official said, on condition of anonymity.

The official also said that the “concern is overhyped” in the context of Kerala, and has maligned the state’s image in the last few years.

“Moreover, if these people are brought back, they will be brought back as terrorists and put straight in jail,” the official said.

Stanly Johny, author of The ISIS Caliphate: From Syria to the Doorsteps of India, also said that Kerala’s “terror problem” has been “overhyped”.

“For a state with 26 per cent Muslim population, 20-odd people joining ISIS isn’t too high at all,” Johny told ThePrint. “The issue was overhyped because people perceive Kerala as an educated, progressive state.”

Perhaps another reason why Kerala is given special emphasis while discussing this issue is because almost everyone who went to ISIS from the state comes from an educated and well-to-do background.

“It’s a myth that radicalisation is a poor people’s problem. Radical and terrorist propaganda can get to anyone, educated and the rich too, as we know now,” he said. “It’s a global problem, hundreds of people from France also travelled to ISIS. We can’t isolate Kerala as it is a global phenomenon.”

(With inputs from Nayanima Basu and Ananya Bhardwaj)

(Edited by Arun Prashanth)