New Delhi: In 2016, two years after the Modi government came to power in New Delhi, the editors of the RSS-affiliated magazines Panchjanya and Organiser, Hitesh Shankar and Prafulla Ketkar, had an audience with Arun Jaitley, with whom they were discussing the place of opinion-makers in society.

Jaitley, the late BJP leader who was considered the key link between his party and the English-speaking, Left-sympathising elite in Lutyens’ Delhi, told the two editors that the English-speaking opinion-makers do not matter anymore. “The narrative is no longer being set by them,” Shankar recalls Jaitley saying.

Ironically, in the 1990s, when the English-speaking public sphere was dominated by the Left, it was Jaitley who slowly and arduously helped cultivate a group of intellectuals and opinion-makers who could put forth the point of view of the Right in the language.

In the course of the almost three decades that have passed in between, the intellectual and media landscape of India has undergone dramatic changes.

The Right-wing intellectual, who, until the 1990s, was jostling for even a token place in the elite English media and academia, has come to dominate this space.

Newspapers, magazines, publishers, organisers of literary fests, for whom the Right-wing intellectual was a persona non grata, and perhaps an oxymoron, until a few years ago, are all lining up for their attention.

There is also the explosion of the pop-intellectual on social media, which has made the gate-keeping in older forms of media pointless.

The Right-wing intellectual space is growing by the day.

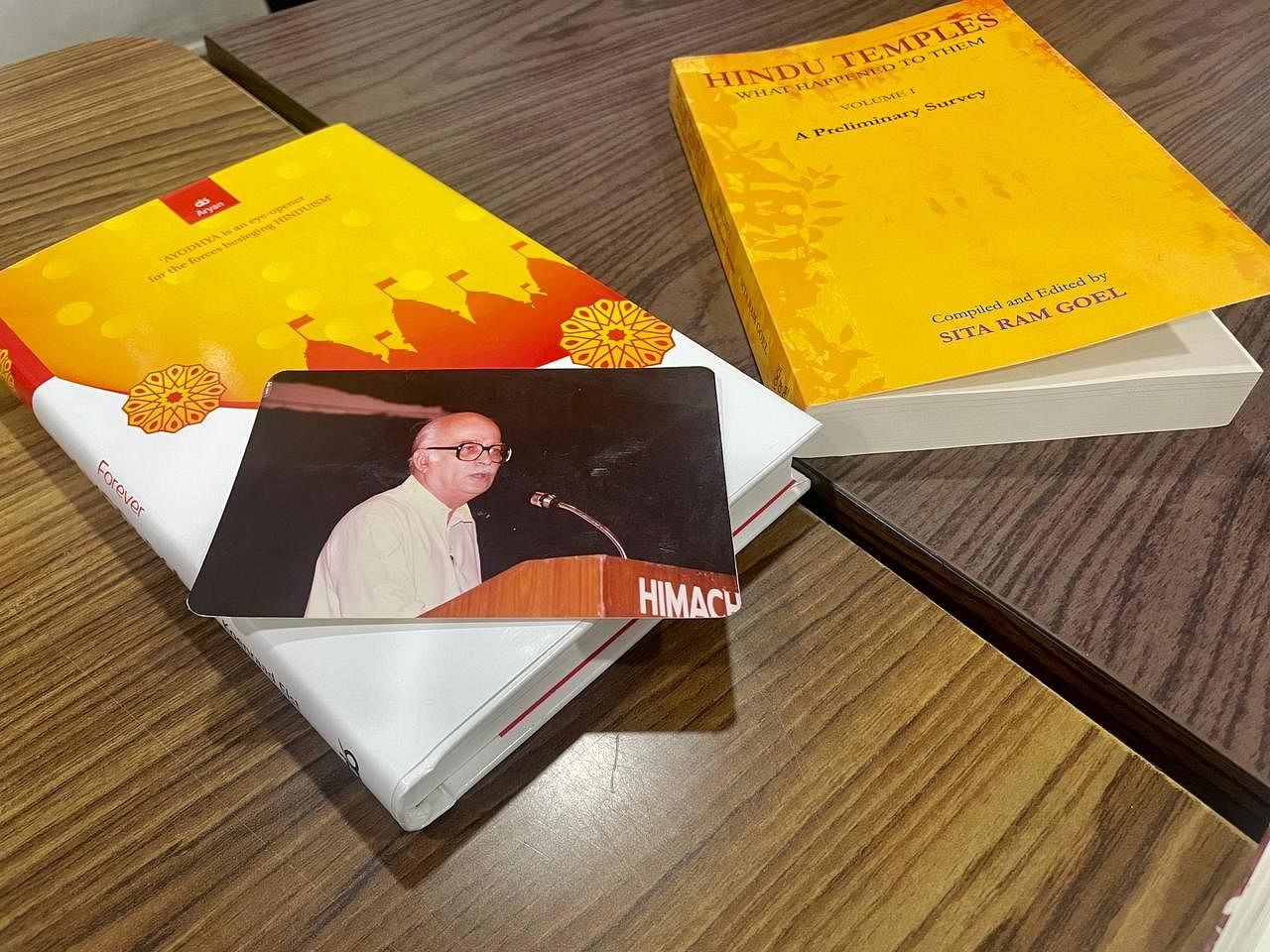

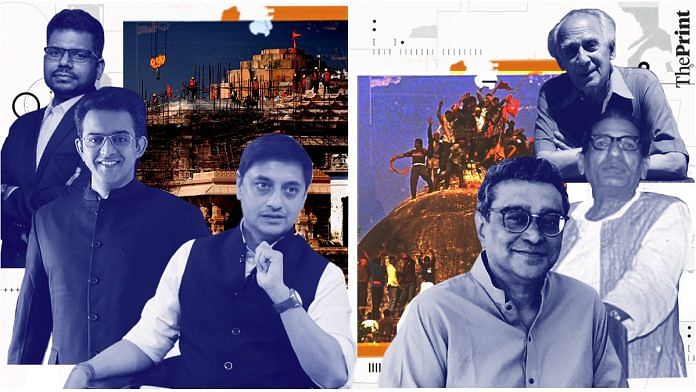

In the 1990s, it was the likes of Arun Shourie, Swapan Dasgupta and Chandan Mitra who managed to make their way into the Left-guarded mainstream. Then there were lesser-known historians like Sita Ram Goel and Ram Swarup, who remained on the margins of elite consciousness, even as they kept denting it through their austerely-produced, but widely-circulated, publications like ‘How I Became a Hindu’ or ‘Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them’.

Now, the public intellectuals, journalists and historians from the Right are at the centre of the new mainstream.

There are the likes of Vikram Sampath, who has produced an exhaustive two-volume biography of V.D. Savarkar, and Sanjeev Sanyal, who has chronicled the lives of armed revolutionaries at the time of India’s freedom struggle.

Then there is J. Sai Deepak, who has introduced the language of decolonisation in popular discourse for an entire generation of readers through the best-selling ‘India, Bharat and Pakistan’ and ‘India that is Bharat: Coloniality, Civilisation, Constitution’.

There is also Anand Ranganathan, Harsh Madhusudan, Rajeev Mantri and Abhijit Iyer-Mitra — to name just a few.

But they are hardly a monolith.

Not only has there been a generational shift between the 1990s Right-wing intellectual and their contemporary counterparts, but the language, intellectual interests, and political and cultural demands have also changed.

Issues of dharma, civilisational glory, and decolonisation, which hardly featured in the Right-wing discourse earlier, are now the go-to staples.

The difference between the earlier lot being ideological adversaries of the state, versus the newer lot aligning completely with the state ideology, is also key.

While the old guard believes that they represented a more inclusive and tolerant strain of Hinduism, the newer lot refutes the claim.

Within the new generation itself, there is a distinction between “trads” and “raitas”.

Trads (short for traditionalists) are apparently the Sanatana Dharma protecting-section of the Right-wing, who are believed to generally be opposed to religious reform, including in matters of caste. “Raitas”, meanwhile, are the pro-reform, pro-caste-equality lot within the Right-wing.

There is also what some call a “pedestrianisation” of the Right-wing intellectual — Swapan Dasgupta and Chandan Mitra, after all, both hold PhDs from Oxford University, while Arun Shourie holds a PhD from Syracuse University.

While there are historians like Sampath among the newer lot, too, the contemporary Right-wing histories are being written by a much more eclectic group of people — from engineers to lawyers.

As stated by Abhijit Iyer-Mitra, “One can now get a book contract on the basis of a tweet.”

What has changed most significantly, however, is the relationship of the new-age Right-wing intellectual with the political and ideological dispensation.

While the old guard was actively cultivated by the likes of Jaitley, and before him, L.K. Advani, the newer lot does not quite enjoy the same kind of political patronage. Neither is Modi’s BJP electorally dependent on them, nor is the RSS dependent on them to advance its ideology.

And therein lies the twofold story of the evolution of the intellectual space in India in the last decade — the unravelling of an earlier Left-dominated elite consensus, and the formation of a new Right-wing populist consensus, which by definition does not need an intellectual elite.

Also Read: RSS, Advani & rise of Hindu Right — where Main Atal Hoon went wrong as Vajpayee’s biopic

The ‘hostility’ of the 1990s

If there is one thing in common with most intellectuals we describe as the “Right” — from old-timers like Seshadri Chari, the former editor of Organiser, and Arun Shourie, the former editor of The Indian Express, to the more contemporary Sanjeev Sanyal — it is their reluctance to use the word “Right” to describe themselves.

“The terms (Left and Right) are borrowed from the French Parliament in 1789 (during the French Revolution) when those who favoured increased veto powers to the King sat on the right and those favoured revolution or change sat to the left of the President,” Chari says. “This Right and Left has no semblance of relevance to the Indian sociopolitical scenario or writings.”

Unhinged from these Western-imported labels, Indian political thinkers — from Mahatma Gandhi to Swami Vivekananda — effortlessly strode across the ideological spectrum, Chari argued.

Moreover, Indian thinkers wrote proficiently in a host of languages, including English — until English education became a marker of Leftist ideology.

Yet, until the 1990s, the ‘Right’ roughly referred to a small number of people who were critics of the planning and public sector economy, says Swapan Dasgupta, who was one of the first intellectuals of the cultural Right to make some space in the English media in the 1990s. “The cultural Right did not make many interventions in the English language at that time,” Dasgupta says.

It was a time when economic, social and political debates were settled in newspaper columns. The India Today magazine or the opinion pages of The Times of India were where elite consensuses were built. “There was Girilal Jain, Jay Dubashi, Arun Shourie, myself, S. Gurumurthy,” Dasgupta recalls as he counts people of the Right, both economic and cultural, who were writing in the English media at the time. “I’m struggling to think of more,” he says.

The absence of the Right-wing intellectuals in newspaper and magazine columns was not for the want of talent — there was an enormous amount of hostility they faced, he adds.

It was not just ideological hostility — there was hostility towards anyone who did not represent the elite consensus, or did not speak sophisticated English, senior journalist Sheela Bhatt says.

“There was no non-elite editor in the English media at the time… Either you were part of the Lutyens’, or you were not,” Bhatt says. Asked what she meant by the “Lutyens’”, a word thrown around quite casually nowadays, Bhatt says it was a “clan” of 3,000-4,000 people — bureaucrats, diplomats, MPs, judges, some performing artistes, top English editors, and cabinet ministers — which was actively nurtured by and prospered under the Congress regime.

“They were mostly upper class, well-educated, spoke with the right accent, had the right dose of arrogance within, knew what’s class and what’s not,” she says.

“They were people… who mistakenly thought that they can change India with the help of only science and technology, and by cutting (it) off from old cultural traditions and religious faith.”

Back in the day, when Bhatt would want to ask now-Home Minister Amit Shah something about a “national issue”, he would often respond to her with the question: “Is what you’re asking to do with those 3,000-4,000 people, or with the actual India?”

“These were people who played golf and decided diplomacy,” Bhatt says. “It’s difficult to imagine anyone with a working knowledge of English, who spoke perfect Hindi, and could recite the Ramcharitmanas, to be a part of this club.”

A host of national and international developments of the late 1980s and early 1990s, however, began to destabilise this tightly-guarded intellectual, ideological and cultural reign of the elite.

It was the time of the decline of the Congress, the economic crisis, the 1991 liberalisation, anti-Mandal protests, the end of the Cold War, and the fall of the Soviet Union. Older consensuses — economic and political — had to now be questioned.

The inflexion point of this social, economic and political churning was, however, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement spearheaded by L.K. Advani in 1990. As the Right-wing began to demonstrate its power on the street like never before, ignoring it in newspaper columns became increasingly difficult.

Arun Shourie played a significant role in this shift.

“No mainstream English newspaper would publish the Hindu point of view on issues — be it temple-mosque disputes, Satanic Verses or the Shah Bano case,” recalls Harish Chandra, the nephew of Sita Ram Goel.

Goel, along with his friend, and intellectual and spiritual “guru” Ram Swarup, was one of the few historians of the Right during the 1980s and 1990s. “Their work was formidable, but among the elite, there was a conspiracy of silence around them — nobody acknowledged them,” Chandra says. “Except for Arun Shourie.”

As the editor of The Indian Express, Shourie routinely challenged the widely-accepted liberal position on matters of religion. In 1989, for instance, he wrote an article titled Hideaway Communalism in the paper, which was widely seen as the first of its kind, wherein a mainstream English newspaper was “breaking the silence” on the alleged history of temple destruction in the subcontinent.

In the coming months, the paper would regularly give space to Goel and Swarup, who wrote a series of articles seeking to establish “the truth” on Islam’s alleged history of iconoclasm and razing temples.

In 1990, Shourie, Goel and Swarup got together to publish Hindu Temples: What Happened to Them. The book, published by Goel’s small publishing house called the Voice of India, known to be Right-of-RSS, was launched by Advani in Himachal House amid a “big gathering” presided over by Girilal Jain, the editor of Times of India, Chandra recalls, sitting in the same office in the mazey lanes of Delhi’s Daryaganj.

The Right’s baby-steps into the mainstream were there for everyone to see, and the English-language media began to be woken from their slumber, albeit grudgingly.

In May 1991, India Today, for example, ran a cover story with the headline “The Rise of the Scuppies”. “Scuppies,” the article said, were “saffron-clad-yuppies”.

Top corporate executives, intellectuals, journalists and lawyers, the piece argued, were quickly turning from “yuppies” to “scuppies”. Their favourite colour was saffron, albeit pale, they wore sparkling white tennis shorts, but with a khaki lining, they were jean-clad and Gucci-hoofed, but were only too happy to be part of the “Ram brigade”, the article said.

Advani himself was deeply invested in cultivating a group of intellectuals of the Right, who could write and articulate its worldview in English newspapers. While he led a movement that had maximum resonance in the Hindi heartland, he was himself an English-wallah. “He would famously say that ‘I learnt Hindi through Bollywood films… My linguistic proficiency is actually English, Sindhi and Urdu’,” recalls Ketkar, the editor of the Organiser.

Swapan Dasgupta, Chandan Mitra, Arun Shourie were all close to Advani, who greatly valued the interventions they were making in the English public sphere.

It was a time when the Right-wing needed legitimacy globally and domestically within the existing system, says a senior journalist who did not want to be named. The idea of the elite consensus itself had not shifted — so the space had to be jostled for within that consensus.

The deregulation of television in the late 1980s, and its absolute explosion in the 2000s, began to shake this consensus foundationally. In the book ‘Politics after Television’, which chronicles the ascent of the Hindu Right in the context of the changing media landscape since the late 1980s, Arvind Rajagopal, a professor of media studies at New York University, argued that “the media re-shape the context in which politics is conceived, enacted, and understood”.

If this context was shaped from the late 19th to the 20th century by the print media — both English for the elite, and Hindi or other regional languages for others— the job was done by television from the early 2000s until 2014, when Modi came to power.

Arnab Goswami, for instance, was key to mobilising middle-class English-speaking nationalism in the final years of the UPA, says another journalist. “The politicised English-speaking public that voted Modi to power was created through the television,” he adds.

Also Read: Hindu nationalism has taken first steps toward establishing a Jim Crow system

The post-2014 Right-wing explosion

Ten years into Modi rule, one can safely say that the Right has never been more mainstream.

In his book, Rajagopal had written that the 1990s English media coverage of the Babri masjid demolition created a “split public”, wherein those who were reading English newspapers were driven to believe that the demolition was the worst blow to their secular democracy, while the Hindi-newspaper-reading public was ecstatic about the country having found a people-led, “democratic” solution to a long-festering dispute.

For this exact reason, Sita Ram Goel consciously decided to write in English. “The Hindi speakers are already conscious of the correct version of history, he would say,” recalls Harish Chandra.

“He believed that it is the English-speaking elite who study at St. Stephens whose minds we have to change… so we must write in their language.”

Thirty-two years later, when the Ram Mandir has been built at the same spot where the masjid was demolished in 1992, the media-consuming public is arguably less “split”. The India Today magazine, which ran its issue with the title “Nation’s Shame” in the aftermath of the Babri demolition, was now running buses with posters screaming “Ram ayenge” in Ayodhya when the Ram temple was consecrated earlier this month.

“When people like Arun Shourie and Swapan Dasgupta were writing, they were mostly critiquing the Left,” says Sanjeev Sanyal, who is a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the PM, and an author of several books, including ‘Revolutionaries: The Other Side of How India won its Freedom’ and ‘The Indian Renaissance: India’s Rise after a Thousand Years of Decline’.

“When we are writing,” he says, referring to his own generation of Right-wing writers and intellectuals, “we are no longer critiquing the Left, we are building a new narrative altogether… And a narrative is never replaced by a critique, it has to be replaced by another narrative.”

But the narrative game is no longer being played on TV debates and op-ed columns alone. There is Twitter, YouTube and Instagram, too, where the following of new-age writers like J. Sai Deepak is unmatched.

Deepak’s podcast interviews on YouTube with journalist Smita Prakash and ‘Beer Biceps’ aka Ranveer Allahbadia, for instance, have over 4 million views each.

A random YouTube search for his name throws up dozens of videos where a “savage” Deepak has “destroyed” and “exposed” “fake secularists” like Shashi Tharoor or Shoma Chatterjee.

Tharoor, who has opposed and debated with the two generations of Right-wing intellectuals, says the new-age intellectuals of the Right-wing are markedly more “abrasive” and “less cosmopolitan” than their older counterparts.

“The older generation of the conservatives in India was far more sophisticated and recognisably more cosmopolitan than the newer lot,” Tharoor adds. “Theirs was a more capacious, broad-minded idea of Hinduism — Swapan, for instance, was anti-Congress, anti-liberal, but never rabid.”

“Nowadays, there is an overwhelming tendency to exhibit Hindu cultural pride rather than the older strain which was to be Right of Centre economically, a traditionalist, and yet be socially liberal,” he says.

Some old-timers within the Right-wing agree.

Unlike the contemporary ones, the interests of the old-timers were hardly in talking about dharma and decolonisation, several of them argue.

“They are far less inclusive these days,” says Sudheendra Kulkarni, a Right-wing columnist and an aide to former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. “Within the Right-wing, if there is an RSS strain and a more aggressive Savarkarite strain, then today, most of these intellectuals belong to the latter,” he says.

“The earlier generation was influenced by reading Nehru, Gandhi, Tagore, Vivekananda, Aurobindo, etc — these writers influenced everyone across the spectrum except for communists — so, the earlier brand of Hinduism supported by the intellectuals was fundamentally more inclusive and tolerant,” he adds.

Much like Chandan Mitra, Dasgupta, and even Sita Ram Goel, Kulkarni, too, was a Leftist before he switched to the Right. Nowadays, with the new generation of Right-wing intellectuals having been raised and educated in a post-Liberalisation India, such crossovers are rarer.

There is also an apprehension of the newer generation becoming more polemical than scholarly, one of the old-timers, who wished to remain anonymous, says.

“They are not quite known for their scholarship as much as they are known for their tweets,” the old-timer adds.

Shourie goes a step further. When he was writing, he was writing against the establishment, he says. “The key difference is that we were challenging the state, and the newer lot is being propagandists for the current dispensation.”

However, not everyone in the older generation sees it that way. Speaking of the new generation of writers, Chari says “they are modern, but not westernised” — echoing the long-held credo of the RSS, which has always claimed to embrace modernity, but on non-Western terms.

Abhijit Iyer-Mitra, a defence commentator — in a viral video, he jokingly referred to himself as the “Orry of intellectuals”, in a reference to the social media personality whose celebrity stems from being photographed with Bollywood personalities — refutes the claims of the old-timers too.

“I don’t agree that the new age of Right-wing intellectuals is less inclusive,” he says. “In the public sphere, however, the extremes tend to congregate and polarise, but it is not as though the whole Right-wing ecosystem has shifted with them.”

The “trads” — the extremely rabid, anti-reform and casteist lot among the Right-wing — might get a lot of traction, but they do not represent more than 5 percent of the conservatives, he adds.

Although, he says, there is a degree of “pedestrianisation” in the Right-wing ecosystem — there is a widespread acknowledgement within the Right-wing that the elite media and publishing institutions have shifted from completely blacking them out just until a few years ago to letting anything they say pass.

But this, Mitra argues, is only an “equaliser” because even in the Left, there were several “bullshit peddlers, whose mediocrity remained unchallenged for decades”.

There is also a sociological reason for this pedestrianisation or democratisation of the Right-wing space.

“The word intellectual is typically reserved for someone who comes from the humanities,” Iyer-Mitra says. “The humanities, as we know, were developed exclusively by the Left, while today’s Right-wing mostly comes from the middle class created after 1991 when services bloomed… So, now we have doctors and engineers writing histories.”

Over the years, moreover, there has been a non-elitisation of the English language itself. It is no longer the language of a small elite with a colonial hangover.

As pointed out by Bhatt, there may still be an enduring aspiration when it comes to the English language, but the source of its aspiration has changed from the British crown to Silicon Valley.

Also Read: Modi’s charisma & Hindutva not enough— Hindu Right press on Karnataka result

The relationship with the BJP-RSS

As opposed to what one would assume, the relationship between the new Right-wing intellectuals and the BJP, or, more importantly, its ideological parent, the RSS, is not uncomplex.

Unlike Advani or Jaitley, there are few active patrons of these Right-wing intellectuals within the political class. “Contrary to his image, it is actually Amit Shah who takes a bit of interest in intellectual stuff… He likes to sit and listen in whatever limited time he has,” one of the persons spoken to for this article says. “In the RSS, it is Dattatreya Hosable, but nobody else, really.”

There is also a question of political dependence. In the 1990s, when Advani and Jaitley were cultivating a Right-wing, English-speaking intellectual group, it was a tacit acknowledgment of the fact that the Lutyens’ is the ground where politics is enacted. It had to be penetrated, but could not be ignored.

Over the last 10 years of the Modi government, the ground where politics is enacted itself has shifted from an elite consensus to a populist consensus. This government, most Right-wing intellectuals themselves agree, needs no interlocutors. “Lutyens’ has not been replaced by a new set of people, the idea of Lutyens’ itself has become redundant,” says Harsh Pant, Vice-President, Studies and Foreign Policy at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in New Delhi, says.

If today, English newspapers are giving Right-wing intellectuals space in their op-ed pages, they are doing so to fight for their own relevance, and not because they are doing some favour to the Right-wing, Shankar, the Panchjanya editor, says.

In fact, within the RSS ranks, there is some suspicion towards those who are believed to “mimic” the ways of the Lutyens’ elite.

Most of the English-speaking Right-wing intellectuals mentioned above have become the face of Hindutva — their books get published by top-notch publishers, their columns regularly appear in the mainstream English newspapers, and their interviews on YouTube garner millions of views.

It is not something that goes down particularly well with the quintessential RSS worker or leader. Those who come from within the RSS system are trained to be the “eternal backroom boys”, and never chase publicity, says an author close to the RSS.

But many of them have jumped onto the bandwagon now, and will say the most sensational things, including constant Muslim-bashing, to get eyeballs, the author adds.

They are, for at least some sections of the RSS, the “neo-Lutyens”.

The tension is, at least sometimes, mutual.

In a podcast interview three years ago on YouTube, J. Sai Deepak, for instance, said that the words “RSS” and “intellectual” do not go together. The almost 100-year-old organisation, he added, has moved away considerably from the “intellectualism” and “vision” of its founders, and has no civilisational and intellectual narrative to counter the Left ecosystem with.

“…The RSS as an organisation over a point of time has reduced itself merely to an organisation that turns up for humanitarian aid and help,” Deepak said in the interview.

To be sure, Deepak is not the only one from within this ecosystem to criticise the RSS. Many years ago, Sita Ram Goel, who wrote regularly for the Organiser, was also profoundly disillusioned by the RSS. “The RSS is the biggest collection of duffers that ever came together in world history,” Shourie recalls him saying often.

The alleged “anti-intellectualism” of the RSS is acknowledged, albeit not always criticised, by others too. An older Right-wing intellectual, who requested anonymity, says that at least until the 2000s, the RSS was distinctly “anti-intellectual”.

“They, in fact, believed that intellectualism confuses society… In that sense, it was well thought-out anti-intellectualism”.

When one of the people spoken to for this article told the fifth sarsanghchalak, K.S. Sudharshan, of the need to document some conversions by missionaries happening in Odisha in 1998, the RSS chief is known to have said, “What document? It has already been published in Panchjanya.”

Many years later, another person spoken to for this article was chided by the current RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat for calling the organisation “conservative”. “Why do you keep saying ‘conservative’? Who said we are ‘conservative’? These are just elite tags,” the person recalls Bhagwat as having said.

The quintessential RSS belief is that social change has to happen slowly from the ground, and not top-down. Intellectualism, in this scheme of things, can be construed as top-down elitism. For instance, the organisation never draws a distinction between its ideologues and activists, Ketkar says.

Yet, the RSS also faces a dilemma. While it fundamentally believes in social change from the ground — through shakhas, education, sports, social work — it cannot look away from the narrative-setting power of the media and social media.

If from Karnataka to Uttar Pradesh to the United States, the Right-wing has been able to consolidate a uniform narrative cutting across local realities, the English-speaking intellectual on YouTube has a definitive role to play.

“The RSS has still not caught on to the idiom of the new-age media — it is both their strength and weakness… So, to that extent, these people may be needed to an extent,” the author close to the RSS says.

This report has been updated to correct a typo

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: Congress boycott right. Ayodhya event not about Ram, but coronates Hindutva as state religion

Well written. Interlaced chronology and multiple viewpoints for this article should have been challenging. End result is worth sharing. , Best wishes to the author and the Print Team. Keep it up!