Imphal/Churachandpur/New Delhi: More than 40 days after violence erupted in Manipur, ethnic fires continue to engulf the state, and bloodthirsty mobs remain caught in an endless cycle of vengeance. This Tuesday, nine people were killed in gunfire at Aigejang village, reportedly as retribution. On Thursday night, a huge mob threw petrol bombs at Union minister RK Ranjan Singh’s Imphal home, setting it afire.

Despite Union Home Minister Amit Shah spending an unprecedented four days in the state, armed forces patrolling the streets, and Chief Minister N. Biren Singh’s pleas, the carnage continues.

The BJP’s much-touted ‘double engine’ model of governance seems to have broken down utterly in Manipur, both at the state and central levels.

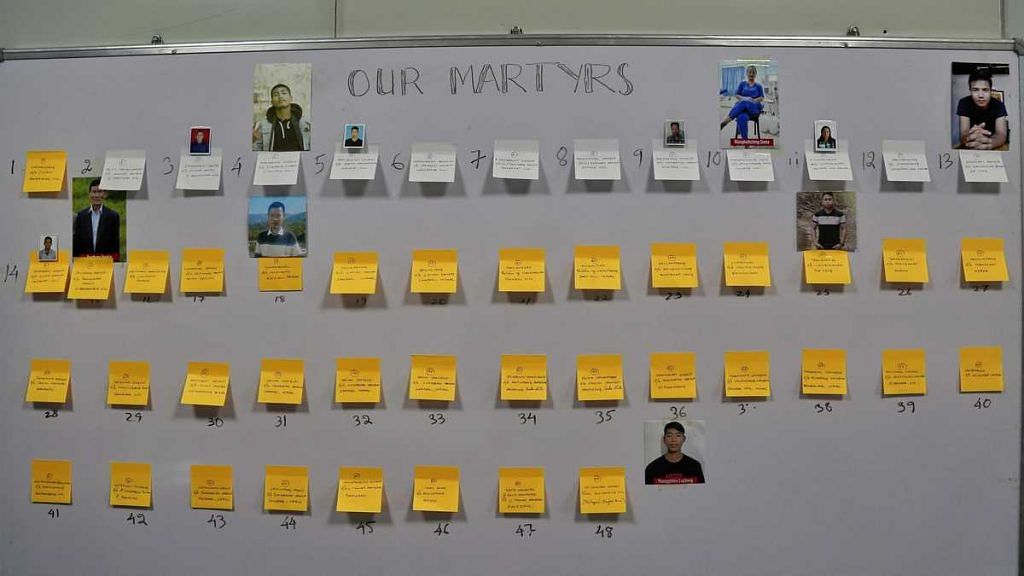

So far, at least 100 people have been killed, more than 300 injured, and over 50,000 displaced from their homes. Over 3,000 weapons, automatic guns to grenades, have been looted, including from police armouries, more than 200 churches and 17 temples destroyed, and numerous houses and properties burnt or razed to the ground.

The perpetrators and victims of the violence come from both communities — the Meitei, who are the majority in the Imphal valley and mostly Hindu, and the Kuki tribals, who are primarily Christians and inhabit the state’s hill districts.

This week, the peace committee formed by the central government to initiate dialogue between the communities collapsed before it even took off. Neither the Meitei nor the Kuki want to participate in talks until the fighting comes under control.

“Before dousing the flames, how on earth can peace talks be initiated? We have been appealing to the state and the central government that they should first stop the non-stop attacking of the villages. In this situation how can we have a conducive atmosphere to discuss peace?” said Khuraijam Athouba, executive member, Coordination Committee on Manipur Integrity (COCOMI), a collective of Meitei civil society organisations.

The Kukis have taken much the same stand, and have also objected to the committee’s inclusion of Chief Minister N Biren Singh, whom they see as partisan.

“The first and foremost thing to do is to stop the violence. Let there be peace first. Inviting leaders to sit together won’t yield a solution until the situation improves,” said Ajang Khongsai, president, Kuki Inpi Manipur, an apex body of the Kuki people.

During his visit to Manipur, Amit Shah blamed a “hasty” order of the Manipur High Court for the conflict. This HC order in April had suggested granting Scheduled Tribe status to the Meiteis— their longstanding demand. For many Kukis, this was unacceptable and seen as a threat to their own ST benefits.

On 3 May, a protest rally against this order, organised by the All-Tribal Students’ Union Manipur (ATSUM) in the hill district of Churachandpur, quickly escalated into widespread clashes.

However, the reason why the fires have been so difficult to contain is that Manipur was already a tinderbox of ethnic tensions, centred primarily on land.

While the Kukis had long claimed that the Biren Singh-led BJP government was targeting them and their land in the name of drives against forest encroachment and poppy cultivation, the Meitei had been protesting over a takeover of the hills by perceived “militants” and “outsiders”— a narrative propagated by the CM himself in public statements.

The fallout of the crisis has been a fractured state, invisible but rigid boundaries between the valley and the hills, and a weak political and bureaucratic machinery— one that failed to prevent and contain the crisis even when it possibly could have.

Also Read: No let-up in violence in Manipur as ethnic conflict enters 2nd month, more troops rushed in

‘Double engine’ breakdown?

On 30 May, tribal women wearing black stood in a human chain along the 2-km road from the Churachandpur helipad to the Assam Rifles campus, where Home Minister Amit Shah was to meet tribal leaders. They wanted to welcome him and convey that he was their only hope for peace.

“We want to tell Amit Shah to stop this violence. Neither the Meiteis nor the Kukis are leading normal lives. We want him to solve the issue as soon as possible. Only he can do it. Otherwise, many more people will die,” Marina Ljoute, a part of the human chain, had told ThePrint back then.

At the time, riots had already been raging in Manipur for 27 days despite military reinforcements and curfews. The Kukis had also given up any hope in Chief Minister Biren Singh, accusing him of ‘majoritarian politics’.

However, Shah’s relatively long four-day presence in the state, his strict warnings to arms looters and underground groups, as well as his appeals for peace to both communities proved fruitless.

The efforts of Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, who is the head of the North East Democratic Alliance (a coalition of the BJP and allied parties in the region), Manipur Governor Anusuiya Uikey, Army Chief Manoj Pande, Kuldiep Singh, security advisor from the central government, and other top BJP leaders, have also come to nought.

Manipur has come to present a peculiar situation for the BJP, flying in the face of its narrative about the double-engine government model as a driver of smooth central-state collaboration, leading to tangible benefits for the population.

Despite the workings of the two ‘engines’, curfew has once again been tightened in the state and a demand for a separate administration has arisen among Kukis, including from BJP MLAs from the community.

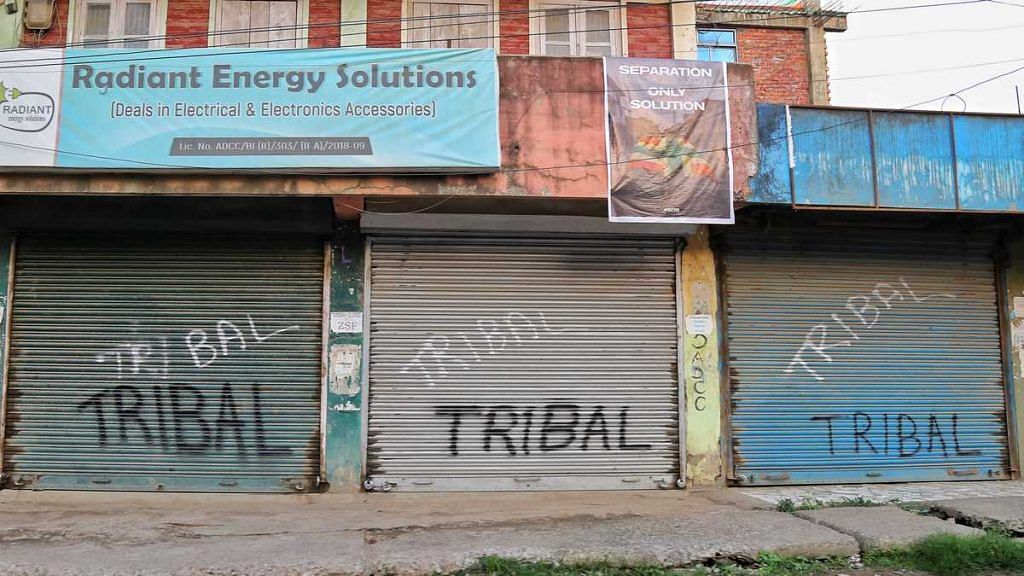

In Churachandpur, banners with slogans like ‘Separation Only Solution’ and ‘Justice Precedes Peace’ popped up this week.

However, this turmoil is not a sudden occurrence but rather a culmination of years of unresolved tensions. The Meiteis claim that the Kukis are providing refuge to Myanmarese refugees, who belong to the same ethnic group, in order to artificially increase the hill population. They further allege the involvement of narco-terrorists in the destruction of the hills through poppy cultivation.

The Kukis vehemently deny these accusations, asserting that the entire community has been unjustly stigmatised.

Even before the conflagration began, the Biren Singh government had been facing pushback on these issues, including from its own MLAs.

In April, a group of Kuki BJP MLAs even visited Delhi to express their grievances against the CM to the party high command. They also warned about public pressure in the hill districts over the government’s drives against ‘forest encroachers’ and poppy growers, and the withdrawal of a ceasefire agreement with two Kuki insurgent groups.

The bloodshed that started on 3 May, therefore, can be seen as a culmination of several underlying tensons that the state and central governments failed to address in time.

‘Ethnic cleansing’

When the mixed neighbourhood of Vaiphei Enclave in state capital Imphal started burning on 4 May, botany professor Tongneilal Vaiphai and his family did not flee. They had made Imphal their home in 1988 and felt safe there. Their delusion was soon broken. A Naga neighbour rescued them in the nick of time, but they had to leave their seven dogs behind.

“We were the last ones to leave,” said Vaiphai to ThePrint. “I have no hope of going back. This fight will not end soon,” he added.

Vaiphai eventually sought shelter at his relatives’ house in Churachandpur after crossing Shillong and Aizawl by road with his wife, an employee at the Manipur Public Service Commission, and daughter, who worked at Manipur Legislative Assembly secretariat.

The capital city, which had once opened its doors of opportunity for the Vaiphais, had become a death trap.

What had started as a clash in Churachandpur on 3 May over reservations assumed a much darker form within hours, casting a shadow across the state.

It was no longer about the ST quota but about eliminating the “enemy” altogether.

Wild mobs ruled the streets of Manipur for days, systematically identifying and attacking the homes, businesses, churches, and temples of the other community.

In Imphal, Kukis were weeded out through their ID cards in colleges, hostels, and workplaces, and then subjected to fatal beatings or left to die.

Similarly, Meiteis in the hills were targeted, and their houses in Churachandpur were demolished using JCB machines. Some Meiteis in Churachandpur sought refuge in the mini-secretariat as a Kuki mob bayed for their blood, according to a district official present at the scene. They were narrowly saved from attack by staff members.

Then came the separation. Stuffed in military convoys, Kukis and Meiteis were transported under heavy protection to the hills and the valley, respectively.

Where separation has been imperfect, there is now constant vigilance.

In ‘border’ areas where Kuki and Meitei villages stand close to each other, security personnel from the Rapid Action Force (RAF), Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), and state police keep stopping vehicles to record licence plate and driver information.

Locals, both Meitei and Kuki women, actively monitor the Imphal-Churachandpur highway, preventing any crossing between territories.

In the villages, the men hide behind sandbags and in paddy fields with weapons, on constant alert.

“The wounds of this trauma will take generations to heal,” says a senior government official who requested anonymity. “The state was progressing in the last six years. The violence will take it back many decades.”

Also Read: IDs checked, skull cracked, ‘dumped alive’ in mortuary — 3 Kuki survivors recount Manipur mob horror

Mayhem, impunity, FIRs piling up

Over the last six weeks, lawlessness and a culture of impunity have taken hold in the state.

Even the political and bureaucratic machinery of the state has not been spared. Most Kuki government officials have left Imphal. Rank and status have offered no protection from rampaging mobs or mutual mistrust within office corridors. Senior police officers, such as then DGP P. Doungel and Additional DGP Clay Khongsai, have also had their houses attacked by mobs.

Some of the state’s top BJP politicians have been targets too. On 4 May, Kuki MLA Vungzagin Valte was beaten and critically injured by a mob after he was returning from a meeting with the CM. On 8 June, bike-borne men threw a bomb at the Imphal West house of BJP MLA Soraisam Kebi.

Meitei MP and Union minister RK Ranjan Singh’s house was attacked not once but twice — first on 25 May when he was inside with his family, and then again on 15 June when a mob set it on fire.

Amid this mayhem, the state’s absence and apathy seem evident.

The state government’s response has been largely limited to internet shutdowns, curfews, and, at the beginning of the riots, shoot-at-sight orders for “extreme cases”.

While CM Singh told the media ahead of Shah’s visit that state police had killed 40 Kuki “militants” during combing operations, leaders of the Indigenous Tribal Leaders’ Forum (ITLF), a grouping of recognised tribes in Manipur, told ThePrint that the dead were only villagers and armed village guards.

Meanwhile, no arrests have been made to hold the perpetrators of street violence accountable in Imphal and elsewhere.

Police stations are overwhelmed with piles of zero FIRs, but processing them is another matter. ThePrint had earlier reported how the Churachandpur police station tried to send FIRs to Imphal through human couriers, but stopped after one try because of the risk.

“The situation in Manipur is not conducive to conducting any investigation yet. Sentiments of both communities are still not normal,” said Khenthang Ngaite, head constable, Churachandpur police station.

Also Read: Police commandos, militants driving Kuki-Meitei violence? In Manipur, accusations fly

‘We don’t trust the central forces’

On 4 May, a day after the riots began, the central government invoked Article 355 of the Constitution and took over Manipur’s security. Five companies of the RAF, 55 columns of Assam Rifles and the Indian Army and 10,000 CRPF and para-military soldiers were deployed in the state. At the behest of the Centre, the Manipur government also appointed former CRPF chief Kuldiep Singh as its security advisor.

On 10 June, the Home Ministry extended the deployment of 114 companies – 52 of the CRPF, 10 of the RAF, 43 of Border Security Force (BSF), four of Indo Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), and five of Sashastra Seema Bal — till June 30.

However, the heavy military presence in Manipur has failed in bringing order to the state. The forces have also encountered difficulties in gaining the trust and cooperation of the Meitei and Kuki communities, both of which accuse them of being partisan.

In Bishnupur, about 27km from Imphal, Meitei women have been blocking central military personnel from crossing over to the hills.

“We don’t trust the central forces. We don’t want them. They don’t protect us. They side with the Kukis. We will stay here and not let them pass,” said Irom Namita Devi, a Meitei resident.

Meanwhile, in Churachandpur, Kuki men who were guarding the border villages told ThePrint that personnel of the Manipur Commandos, a state force, were complicit in burning homes and giving cover to the Arambai Tenggol, a Meitei armed group.

The state government has denied these allegations, but the trust deficit is a problem in itself.

Contested lands

A valley surrounded by hills, Manipur is shaped like a bowl. While the valley districts— Imphal East, Imphal West, Thoubal, Bishnupur, and Kakching—are dominated by Meiteis, the northern hills are primarily occupied by the Naga tribes and the southern ones by the Kukis.

Going by the 2011 Census, the Meitei account for approximately 53 per cent of the state’s population of 28 lakh, the Kukis around 28 per cent, and the Nagas about 21 per cent.

However, the vast majority of the Meitei population resides in just 10 per cent of the state’s land area, while the remaining 90 per cent of the land comes under the hill districts.

According to the Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act, 1960, non-tribals cannot buy land in the hill areas, which means that large swathes of the state are off limits to the Meitei, most of whom come under the general category. On the other hand, Kukis have no restrictions on buying land anywhere in the state.

Many Meitei feel bitter about this and it is one of the reasons why they have been seeking Scheduled Tribe status.

“We (the Meitei) are the indigenous people of Manipur and we cannot have access to majority of the land in the state. Kukis are not indigenous people of Manipur. Whenever the Kukis find an opportunity, they take up land in Imphal. It is their hidden agenda to eat up our land. We will be able to protect our land if we are also ST,” said M Manihar Singh, petitioner in the case in Manipur High Court demanding ST status for the Meiteis.

Though this fight over land between the two communities is old, the policy decisions by the CM, especially targeting poppy cultivation, has infuriated the Kukis. To them, it feels as if the CM is trying different ways to grab their land.

Divisive narratives, poppy to ‘population explosion’

A number of flashpoints have emerged between the Kuki and Meitei communities over the last few years. Some of these issues were sparked by the policies and statements of the Biren Singh government, while others were further aggravated by them.

These include the interlinked controversies around poppy cultivation, “illegal immigration”, and forest encroachment in the state, all leading to varying degrees of unrest over the last few months.

When Biren Singh started his first term as Chief Minister in 2017, he immediately started making good on his poll promise to tackle illegal poppy cultivation in the hill districts. In 2018, he launched his ‘War on Drugs’.

However, after his re-election last year, Biren Singh’s narrative for the ‘War on Drugs 2.0’ underwent something of a shift. He explicitly stated on public record that “militant outfits” and “illegal immigrants” were driving illegal poppy cultivation— seen by many Kukis as a dog whistle.

“The government has called Kukis poppy cultivators, immigrants. These are just excuses to grab tribal land. There are just fabricated stories,” said Pagin Haokip, ITLF chairman.

According to state government data, poppy cultivation in the state tripled in five years since 2017, from 1,853 acres to 6,742.8 acres.

The Kukis, however, claim that the figures of poppy cultivation by the state are exaggerated and they are being unfairly singled out.

The other issue on which the Meiteis and Kukis have been at loggerheads is a purported influx of illegal immigrants from Myanmar.

The perception has grown that the Kukis are harbouring Myanmar refugees, many of whom belong to the same ethnic group, namely the Kuki-Chin-Zomi-Mizo tribe.

“Kuki migrants from across the border are being harboured and given shelter in Kuki areas. They have been mobilised to establish new villages,” claimed Athouba of the Meitei collective COCOMI.

Meitei leaders have drawn attention to census data from 1950 to 2011, claiming that the five Kuki-dominated hill districts of Chandel, Churachandpur, Tengnoupal, Kangpokpi, and Pherzawl have witnessed an unusual surge in the number of villages. A purported leaked government report also indicated that approximately 1,000 villages in the Kuki hill districts have sought recognition.

However, Kuki leaders attribute this increase to the movement of the community within the state rather than an actual population growth.

“These are all wild allegations. In the 1990s, during the Naga-Kuki conflict, those Kukis who had settled in Ukhrul, Kamjong, Tamenglong and Senapati districts, took shelter with their relatives in other districts. So, shifting of the population from one district to another doesn’t count as an increase in the population,” said Kuki Inpi Manipur president Khongsai.

ThePrint previously reported on how Manipur’s porous border and ethnic and cultural ties with hill communities in Churachandpur make it a preferred shelter for families fleeing from Sagaing and Chin in Myanmar. The exact number of settled immigrants remains unknown, but the fear of demographic change has heightened anxieties among the Meiteis.

In this context, CM Singh’s divisive narrative, labelling Kukis as “poppy cultivators” and “immigrants,” has helped foment fear and anger in both communities.

Last year, Meitei and Naga groups demanded an exercise similar to Assam’s NRC in a memorandum to the CM, claiming it would address illegal entry.

Placards by Meitei women blocking the road leading to Churachandpur even now say, “no golden triangle in Manipur” and “save indigenous people from immigrants”, among others.

The Kukis, meanwhile, were furious that the government was seemingly trying to force them out of their own homes and land.

The strike of a match— lead up to violence

In the backdrop of these simmering tensions, the government did little to diffuse the Kukis’ distrust. Instead, it conducted surveys and eviction drives in the reserve forests, intensifying tensions.

On 20 February, the forest department went in with JCB machines to K. Songjang village in the hills of Churachandpur and demolished 16 Kuki tribal households for purportedly encroaching on protected forest land.

By early March, the situation in Manipur was already tense over multiple issues, from Meitei calls for action against “illegal immigrants” to a clash in Kangpokpi between security forces and Kuki groups protesting the eviction drive.

On 10 March, the state government withdrew from a Suspension of Operation (SoO) agreement with two Kuki rebel groups, with the CM blaming them for “influencing” the agitations.

Also, discussed reviewing the Suspension of Operations (SoO) agreement, particularly with the ZRA and KNA who are allegedly influencing the agitations after the eviction noticed were issued to the forest encroachers.

— N.Biren Singh (@NBirenSingh) March 10, 2023

Then, on April 11, the state government demolished three churches in Imphal because they had allegedly been constructed without permission on government land. Three days after that, the CM tweeted that further land surveys would be conducted in Churachandpur.

After a thorough discussion we have come to an understanding and further survey will be conducted in consultation with the village chiefs and concerned authorities.

— N.Biren Singh (@NBirenSingh) April 14, 2023

For many Kukis, this caused anger to only grow.

On April 27, a group of Kukis allegedly vandalised an open gym which the CM was scheduled to inaugurate in Churachandpur the next day. But Singh was also adamant, said a senior official to ThePrint on the condition of anonymity.

“The CM took this insult as a personal attack. He insisted that he would go for the inauguration. He cancelled the plan last minute when he was told that the situation is not fine,” he said.

Meanwhile, the evictions led to Kuki tribal bodies calling for a shutdown in Churachandpur on 28 April. The day passed peacefully, but by evening clashes broke out between security personnel and locals, as well as incidents of arson. A forest office was also burned.

Days later, ATSUM called for its tribal solidarity march to demonstrate against the “persistent demand of Meitei community for inclusion in ST category and the support to this by valley legislators”.

There are conflicting accounts of how this event on 3 May spiralled out of control.

The Kukis accuse the Meiteis of initiating the violence by placing a burning tyre under the Anglo-Kuki war gate in Churachandpur and attacking Kuki villages. On the other hand, the Meiteis claim that the Kukis came prepared to attack them after the rally, and their villages retaliated in self-defence.

Manipur has seen violence before, including the Naga insurgency after its merger with India in 1949 and clashes between the Meiteis, Nagas, and Kukis in the 1990s. However, the current riots between the Meiteis and Kukis mark one of the bloodiest clashes in nearly three decades.

The police have yet to recover looted automatic weapons, grenades, tear gas shells, and other weapons that may have fallen into the hands of mobs.

Although both sides claim that they are only using their licensed single-barrel guns to defend their villages, the injured and the dead in the hospitals are arriving with sharp gunshot wounds, possibly inflicted by automatic weapons, doctors at Churachandpur told ThePrint.

‘Complete ignorance’

The ongoing conflict has opened old scars and inflicted new wounds, making the path towards peace seem increasingly elusive.

But Home Minister Amit Shah, during a briefing in Imphal, attributed the violence only to the court order, contrasting it with the six years of development and peace experienced under the BJP-led government in Manipur.

“For six years, since the BJP formed the government in Manipur, the state saw no blockages, curfews or violence. Under the leadership of Narendra Modi and the chief minister, BJP’s double-engine government in Manipur saw progress… But in the last month, violence has erupted in Manipur because of a hasty court order,” he said.

The magnitude of the fallout, however, tells a different story.

Since the fight began, Churachandpur has symbolically snapped its ties with Imphal and from the Manipur government. The names ‘N. Biren Singh’ and ‘Government of Manipur’ have been covered in black spray paint on all government buildings, shops, and signages. So has the name ‘Churachandpur’— the locals now want it to be known as ‘Lamka’.

Mizoram’s capital Aizawl has become the essential lifeline for the hill district, providing daily supplies. Imphal airport is out of bounds for the Kukis now. If they have to fly out of Churachandpur, they take a 15-hour road journey to reach Aizawl airport.

Recognising the gravity of the situation, Shah announced a helicopter service for the airport from the hill districts at the rate of Rs 2,000 per person.

But these temporary solutions will not restore peace in Manipur, say Meitei and Kuki leaders.

“When the Home Minister says that this all happened because of Meiteis’ demand for ST status, it’s complete ignorance. When the Chief of Defence Staff says that the conflict has nothing to do with counter-insurgency, that is also complete ignorance and denial. Because of this, they are unable to effectively execute any tasks in Manipur,” said Athouba.

The Kukis also had high expectations from the central government to ease the conflict, but their hopes are fading.

“What is the difficulty in stopping the problem? Manipur is a tiny state where thousands and thousands of military and paramilitary forces are not required,” Khongsai said. “The government has enough security, they can deploy them anywhere. A buffer zone can also be created at any point of time. The situation in Manipur currently is not democracy, it’s mobocracy,” he added.

The rift between the Kukis and Meitei runs deep, but they have in common a growing disillusionment with the central government.

A photo of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Manipur is doing the rounds on Twitter. “Have you seen this man?” says the caption. “Last seen at Manipur Legislative Assembly Rally.”

Since the riots started, Prime Minister Modi has neither visited Manipur nor issued any statements on the crisis.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Manipur is burning because of North Block’s legendary ignorance of the Northeast