Churachandpur: A worn-out chair, rotten fruits strewn on the ground, a now-dry water tap on a hill slope, a broken signboard announcing a “plantation of horticulture” scheme from two years ago under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), and a few lemon saplings growing steadily — these are all that remain of K. Songjang village in Manipur’s Churachandpur district.

“They came with six JCBs and uncountable police and forest personnel. They threw stones at the poultry coops, took away the chickens, destroyed the pigsty, and towed away the squealing pigs,” recalled former resident Douminlal, 31, pointing to the emptied land where his house once stood.

State authorities evicted this tiny settlement, once home to 16 Kuki tribal households, on 20 February for purportedly encroaching on protected forest land. However, tribal groups protested that the N. Biren Singh-led BJP government’s eviction drive was targeting legitimate residents.

The events at K. Songjang set off a chain of profound consequences — for the government as well as the local population, feeding into Manipur’s struggle with resentment among different communities on various issues.

Most of these disputes revolve around issues of land ownership and resource allocation, and have at times led to serious violence.

The last few months have seen a steady build-up of conflict and strain in the ties between two communities — the ethnic Kuki tribals in the hills and the dominant Meitei population or the non-tribals living in Imphal valley.

The Kukis, in particular, have been voicing their grievances against several issues — evictions and land surveys in Kuki villages, “discrimination” over the issue of ethnicity, alleged biases, and inadequate representation in the legislative assembly.

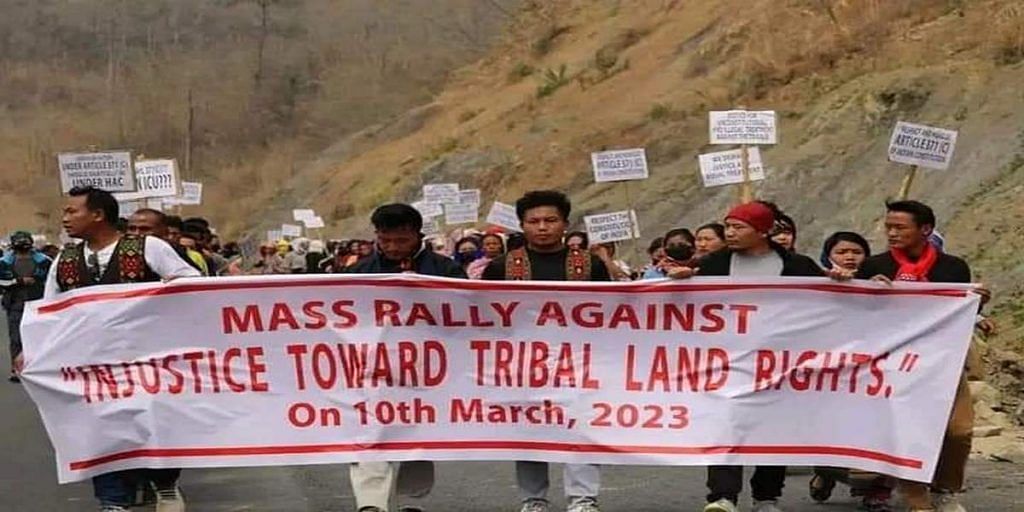

The state witnessed protests in March and April over the evictions, and another flare-up in May after the Tribal Solidarity March called in protest against the demand for Scheduled Tribe status by a section of Meiteis.

On 3 May, following the solidarity march by the All Tribal Students Union of Manipur (ATSUM) on the reservation issue and the protection of tribal rights in general, clashes broke out in Churachandpur and surrounding areas, soon spreading to adjoining Hill districts and the Imphal valley.

Both sides used guns, clubs, and metal rods against each other — in a way the state has never seen before. Houses were burned down, religious structures destroyed. At least 60 people died, many more were injured and displaced.

“Land is a kind of identity for the people. The tribal people are deeply attached to their land. But because of government policies or undue processes followed in the declaration of reserved forests, protected forests, or wetlands, there were a lot of grievances among the affected people. This and various other issues led to the Tribal Solidarity March on May 3,” said Mangcha Haokip, a research scholar from Churachandpur.

So, how exactly does the remote village of K. Songjang fit in with these developments? ThePrint visited the village and its surrounding areas on 30 April to understand its significance within the broader context of Manipur’s ongoing challenges.

Also read: Gunfights, IED fuel fears over security in Manipur. Situation ‘stable’, says military officer

What happened at K. Songjang?

Douminlal and a few other former residents of K. Songjang visit the eviction site almost every day, sitting by the ruins and swapping stories about the once-thriving village, located about 43km from the Churachandpur district headquarters.

When the JCBs rolled in to raze the village on 20 February, many of K. Songjang’s children were still at school, said 75-year-old village chief Lhunthang Haokip.

“On returning, they found their homes had disappeared. The authorities took away the tin sheets and logs used to build the houses. The children lost their text books and stationery,” he added.

Lhunthang recounted resisting the authorities when they first approached for the demolition.

“We were not letting them carry out any eviction. But the police and forest personnel repeatedly requested me to let them demolish only two kutcha houses, so they could send the pictures to the chief minister as proof of the job being done. When we agreed to that, they went on to demolish the whole village,” Lhunthang alleged.

He claimed that he requested a senior police official for a little time to collect their belongings, but was denied.

“We had a church here that was also demolished. They took away the sound system and benches. They even took away our Aadhaar cards,” he said.

Before the demolition, say villagers, six houses and a church were perched on a hillock, while 10 other dwellings stood on the edge of Old Cachar Road and down the slope.

The villagers, mostly farmers, had cultivated lemon, yongchak (tree beans), and banana trees, some of which can still be seen. They also grew and sold crops such as chickpeas, cabbage, hawai thrak (a type of pea), ginger, potatoes, and chak hawai beans, the most profitable of the lot.

These sources of livelihood have disappeared now.

“We are living hand to mouth. For farming, villagers have made makeshift huts around the slope. Some stay there for the night. The beat officer of the forest department comes to check every day, but he hasn’t said anything. Without houses and having lost our farming tools, we don’t know how to survive,” Lhunthang added.

Those evicted from K. Songjang are currently taking shelter in the next Kuki village of Joujangtek, about 4km away. There are around 120 displaced people including about 30-35 children, the village chief told ThePrint.

Why did protests follow eviction?

While the government has claimed that the village encroached upon a stretch of the Churchandpur-Khoupum protected forest, local tribal bodies allege that such evictions unfairly target Hill communities because of their ethnicity.

This dispute is linked to the larger context of Meitei groups expressing concerns over an influx of “outsiders” to the state, particularly refugees from Myanmar.

As reported earlier by ThePrint, many of these refugees largely belong to the same ethnic group, namely the Kuki-Chin-Zomi-Mizo tribe, bound by ethnic and kin ties.

The tribe, it should be noted, is known by different names in different regions. Those living in Chin Hills (Myanmar) are called ‘Chin’, while those residing in Manipur and Assam are known as ‘Kuki’. Tribespeople in the erstwhile Lushai Hills, now Mizoram, are often referred to as Kuki-Chin-Lushai or Mizo.

Currently, many scholars collectively refer to this group as ‘Zo’ people based on the broad historical, anthropological, and linguistic affinity of the group.

On 10 March, the Indigenous Tribal Leaders Forum (ITLF) submitted two memoranda to the CM and Governor in March. Apart from the issue of eviction, the ITLF stated it was “discriminatory, derogatory and unforgivable” that tribal communities were being treated like “foreigners or Myanmarese in their own land”.

The memoranda also alleged that the government had declared the Churachandpur-Khoupum Scheduled Hill area as a protected forest, without seeking the approval of the Hill Areas Committee or in conformity with the provision of Article 371C of the Indian Constitution — charges denied by the government.

That same day, clashes with security forces erupted between protestors from the Kuki Students Organisation (KSO) and the ITLF in Kangpokpi district over the eviction drive in hill villages, including K. Songjang. There were also protests Churachandpur, Chandel, and Tengnoupal, but these stayed peaceful.

On 28 April, sporadic incidents of violence were reported from various parts of Churachandpur district following an eight-hour shutdown call by the ITLF, as part of its strategy of “non-cooperation with all government-related programmes” due to the evictions and other factors.

‘Encroached forest land’ or not?

Village chief Lhungthang told ThePrint that he learned about the existence of the Khoupum protected forest “solely through a show-cause notice” issued by the government on 10 August last year.

However, the state Forest Department asserted in a communique published by news outlet EastMojo in March that it had sent a second show-cause notice to the village chief on 30 January, to which a reply had been received on 6 February.

Subsequently, on 10 February, the chief was informed by the Noney divisional forest officer (DFO) that the “encroached forest land” should be vacated as creation of new villages is not valid inside the Protected Forest.

On 20 February, an eviction drive was carried out by a team of Noney Forest Division, and police teams from Noney, Kangpokpi, and Bishnupur districts.

In its press note, the forest department further claimed that the “so-called K. Songjang village” was “established only in the year 2021” by illegally encroaching on the Churachandpur- Khoupum Protected Forest.

It also stated that the Churachandpur- Khoupum Protected Forest was notified under Section 29 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927 by the Government of Manipur with a well-defined schedule of boundaries through notifications dated September 1966.

Lhungthang, however, said that K. Songjang was not new, but merely bifurcated from Kungpi Naosen, a larger village — often referred to as a “mother village” in Kuki traditions.

Speaking to ThePrint, Lalam Hangshing, general secretary of the Kuki People’s Alliance, a regional political party that formed last year, elaborated on this.

“One peculiarity with Kuki villages is that, with population growth, they tend to splinter into satellite villages, which would all be within the demarcated area of the original mother village,” he said. “The present government had painted these as a proliferation of illegal immigrants without verification and resorted to eviction.”

According to village chief Lhungthang, residents like him have deep roots in the area.

“My parents settled in the mountains in the 1800s. There were big stones around, and we dug them out to expand the place,” he said.

“In 1958, government officials came for a road survey, and I also joined in to dig and build it. But now they claim that this forest was notified in 1941 (he said the government official told him it was 1941). The divisional forest officer presented a map, claiming it was a photograph taken in 1941 and that there was no village at that time,” he continued.

“These are the Haosapu Moul mountains where Japanese soldiers had established camps during WWII. I remember my mother telling me that this place looked bright day and night due to artillery shelling,” he reminisced.

Sources in the government, however, denied this claim.

Notably, the forest department in its press release had rebutted the claims of the village chief that K. Songjang had been bifurcated from Kungpi Naosen, stating that there was “no record” of this. It added that establishing “a new village in the name of bifurcation” post the notification of a protected forest was in violation of the Forest Act, 1927.

On 30 April, Union minister Bhupender Yadav further clarified to mediapersons in Imphal that the protection of forests is the constitutional responsibility of the state government. He also noted that ownership of forest land has rested with the state ever since the Forest Act 1927 came into effect after independence.

Court battle so far

Two writ petitions have been filed in the Manipur High Court to contest the government’s claims about K. Songjang — one by Gracy Lamkholhing, daughter of village chief Lhungthang Haokip, and another by Thengkhogin Haokip, son of Tongkhopao, the late village chief of Kungpi Naosen.

Court documents, accessed by ThePrint, highlight the various legal implications and grey areas that have arisen around settlements in “protected forest areas” ever since the pre-independence era.

One of the key arguments is that an assistant forest officer (ASO), appointed as an Enquiry Officer in 1971, had passed an order in 1986, excluding various villages including Kungpi Naosen, from the territorial jurisdiction of the Churachandpur-Khoupum Protected Forest area.

The state government, however, has argued that this order is now null and void since the officer’s mandate was only to conduct an enquiry on the “existing rights” of communities living in protected forests and to submit his findings to the state government.

This ASO, the state has asserted, was “not authorised or empowered to exclude lands from the protected forest”.

The state government also pointed to the fact that it had appointed a committee in June 2022 to examine the contentious order.

Thereafter, the state government said, the old order had been cancelled on 13 December 2022 and fresh enquiries ordered “on the nature and extent of existing rights of the people prior to the notification of protected forests”. These enquiries were to be carried out under representatives of the concerned deputy commissioner of the district as well as the director, Settlement and Land Record. This state government order was approved by the Governor of Manipur last year.

In its memoranda, the ITLF had stated that the government’s act of initiating a process for the village chiefs to produce legal documents before the forest officials was “nothing but a trap”.

Lhumthang could, however, produce documents in the form of a July 2007 approval by the state government in recognition of K. Songjang as a “full-fledged Hill House Tax Paying village” under the Henglep sub-division of Churachandpur. He also has in his possession a few Hill House tax receipts.

The Manipur High Court issued an interim order on 28 February in the matter of the villagers’ petitions, ordering “status-quo to be maintained by both the parties”.

‘We will die here’

Gracy Lamkholhing points out that for years the residents of K. Songjang lived and worked, without ever expecting they would one day not be considered legitimate residents.

She says about 6,000 lemon, orange, and yongchak saplings were planted here under a government scheme.

“There were eight households built under Pradhan Mantri Adarsh Gram Yojana (PMAGY), we were connected with Jal Jeevan mission, and there are MGNREGA job card holders from all the 16 households,” she added.

According to her, K. Songjang had always steered away from illegal activities such as poppy cultivation, which has been a major target of the Biren Singh government’s war on drugs— another issue on which Kukis claim they have been unfairly targeted.

A total of 2699.8 acres of poppy cultivation were destroyed in Churachandpur district alone in the past five years, according to government data.

“My father was asked by some people if he would allow them to cultivate poppy, but he refused,” she told ThePrint.

Meanwhile, 58-year-old Ngaikim, who had returned from collecting wild greens (anjou) from the mountains, said she lost almost everything in the demolition.

“I was present during the demolition. I could take out few items, but there’s no place to keep them,” she said. Ngaikim is staying at a makeshift camp in the slope while her family of seven has rented a house in town.

“We used to farm chickpeas and sell it here itself. We have not cultivated anything in the past three months. Our major worry is where the next meal will come from,” she added.

Henkhopao Haokip, 47, the village chief of adjoining Joujangtek said they were doing their best to help their neighbours.

“We are receiving donations from people and churches for the relief and rehabilitation of the people. From every household of Joujangtek, we collect rations and give it to the families of K. Songjang,” Haokip said, adding there are about 60 households in his village.

According to him, K. Songjang has been part of the Kungpi Naosen area for a long time, explaining that it is common for tribal communities to shift domiciles, depending on factors like water supply and road connectivity.

“It’s not a new village. The elderly folk in every village know about K. Songjang. The area is Kungpi Naosen,” he said.

Lhunthang told ThePrint that he has advised villagers to hold their ground.

“We have asked people not to be scared or scattered, and stay here. We will wait for the court order. We will die here and not give up,” he asserted.

Echoing his sentiments, two of the villagers, Thangjang, 49, and Hemmang, 39, said they had no intention of leaving.

“We will stay. Let us live like the good old days,” said Thangjang.

“Whoever can help us, please do so,” added Hemmang.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)