New Delhi: It’s close to midnight at this South Delhi nursery and on this January day, Bhim Army chief Chandrashekhar Azad is surrounded by a small band of men — the quiet far removed from the electrifying atmosphere that Azad has of late become accustomed to.

Just before heading here, having been granted bail by a Delhi High Court in a case of inciting violence and unlawful assembly, Azad was at Shaheen Bagh, where women have taken the lead in protesting the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

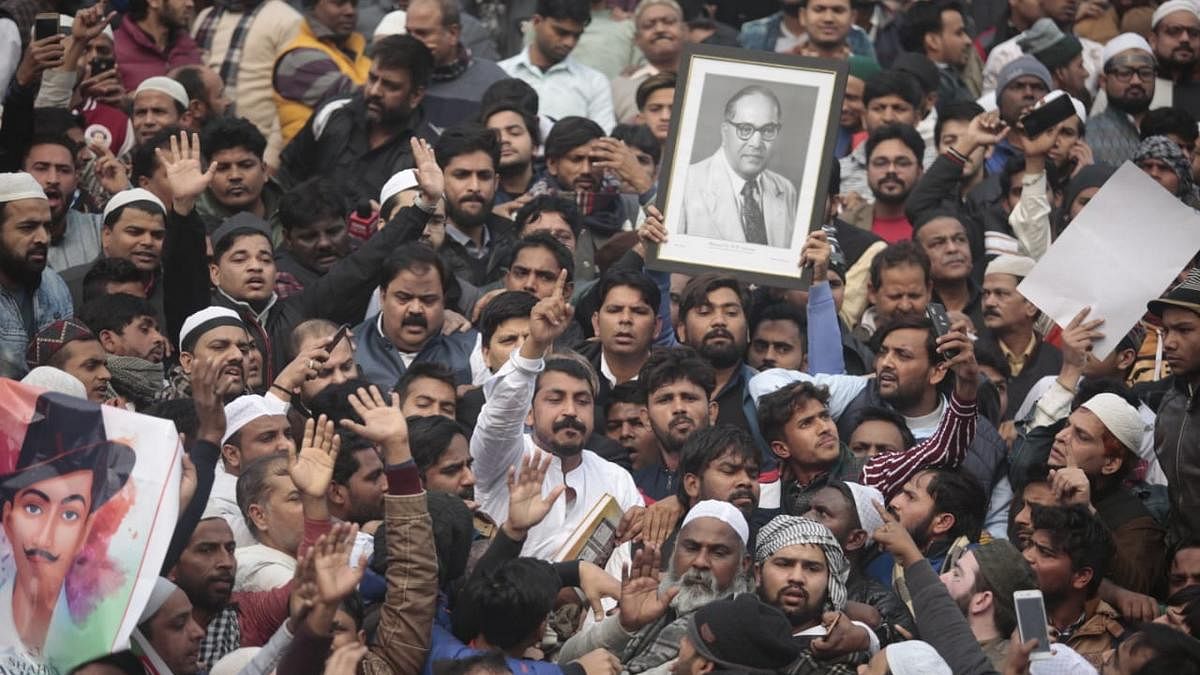

In a captivating speech, he had the crowd on its feet, promising to protect the Constitution as shouts of “Jai Bhim” reverberated through the packed street.

At the nursery, in relative silence, one of the men in the group — all Bhim Army volunteers from across northern India — offers to sing.

“He will wait until he has met every one of them. They’ve come from far to meet him, and he will hear them out,” says a young member of the crowd who is affiliated with the Bhim Army’s newly-launched Student Federation.

Azad just then indicates to the eager volunteer that he may sing.

“The Bhim Army gives us strength, stirs us to come to the Centre

After years of oppressive governance, we are called to rise up

Chandrashekhar Azad, born to Kamlesh Devi on 3rd December…”

The man sings before being interrupted by the Bhim Army chief.

“Is this song about the revolution or is it about me?” Azad asks.

The singer, bashful as ever, makes it clear that it is about both. The song then goes on, describing Azad as the new face of Dalit resistance before concluding with the line: “The Constitution will prevail.”

In effect, it encapsulates the rise of Azad, from a local leader in Western Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur district to the face of Dalit empowerment and a rallying point for the resistance against the Modi government.

The Dalit leader has captured the imagination of the nation as the anti-CAA protesters, particularly in the national capital, have whole-heartedly embraced him. He has even loosely inspired the character of Nishad, a Dalit activist in Anubhav Sinha’s acclaimed film Article 15.

Azad also appears to have done enough to spook some state governments.

Barely a week after he was released on bail from Tihar Jail in Delhi, Azad was arrested in Hyderabad on 26 January, where he was due to address students on the CAA issue. On 29 January, he was to speak at a college in Bengaluru when it withdrew permission and abruptly called off the event.

He has also had to contend with legal troubles. Azad has been slapped with over 30 cases, including the grave charges of murder and jeopardising national security.

But the larger question remains. Will all of the adulation result in political capital when Azad does take that route?

“I have never considered myself a political leader. So many years of politics in independent India and the status of our people is largely the same. It hurt me. I wanted to end it. That’s why I started the Bhim Army,” Azad tells ThePrint.

“But Babasaheb Ambedkar taught me that politics is the next necessary step. If you don’t speak up for your own people, who will?”

Azad is confident the Bhim Army — an organisation formed with the aim of educating Dalit youth and fighting caste atrocities — will fight the assembly elections in his home state, Uttar Pradesh, in 2021. But it will be under a different moniker, and the party will exist parallel to the organisation in its current form.

Also read: The Mayawati era is over. Bye Bye Behenji

Coming of age

Even though the Bhim Army was founded in 2015, its seeds were sown years earlier.

Azad was born on 3 December 1986 and grew up in Chhutmalpur, Saharanpur, a district in western Uttar Pradesh where about 22 per cent of the population belongs to the Scheduled Castes (SC), and 45 per cent are Muslim. The demographic has earned Saharanpur the reputation of being a Dalit stronghold and has been a political battlefield for decades.

In 1998, BSP founder Kanshi Ram launched his political career from Saharanpur. He didn’t win, partly because he wasn’t native to the area but the effect of his campaign left a deep impression on the district.

“But for Saheb (Kanshi Ram), we would never have had the courage to rent a vehicle and travel outside the village. Saheb told us and showed us that we too have the right to make use of all the facilities enjoyed by other communities,” a Dalit agricultural labourer had said at the time of Kanshi Ram’s death in 2006.

Azad would have been 12 years old when Kanshi Ram stood for elections in his home district. “The struggles of the Bahujan Samaj have taught me everything I know about resistance,” Azad says. “My father lived to see that and I grew up hearing about it. That’s what informed my politics and where I drew my inspiration.”

Azad’s father was a school principal who suffered caste discrimination.

“He wanted me to become a judge because there’s pretty much no Dalit representation in the judiciary,” Azad says. “We’ve never had the chance to dish out justice and he wanted me to have that.”

Azad enrolled in an LLB programme in Dehradun’s D.A.V. College, where he was part of a progressive student group called Satyam. Although it isn’t affiliated to a political party, the group competed in the college’s student union elections and proved to be a useful network when Azad turned to activism after graduating in 2007.

In 2012, Azad moved back to his village when he heard that Dalit students in a Thakur-run college were made to sit separately, had their money stolen and their books vandalised. They were allegedly permitted to drink water only after their upper-caste peers and were allegedly threatened with violence if they dared to speak up. A young lawyer, Azad was aghast that the administration hadn’t stepped in.

“My first protest was against this college. Schools are meant to ensure equality,” Azad says. “I spoke with the administration, which constituted a useless committee that did nothing. So we began protesting outside it. The Bhim Army also started this way, as a school system by Dalits for Dalit students to ensure discrimination like this comes to an end.”

Azad often crossed paths with Vinay Ratan Singh — another activist in the area — during local protests, such as the one outside the Thakur college. I asked Singh, who is now the Bhim Army’s national president, as to what Azad was like before he became a public figure in 2017.

“Same,” says Singh. “He would always be present when he heard about any rape or violence. He would always speak up, and always show up. That’s just what he’s like.”

In 2015, the two decided to seriously act to support Dalits caught in the midst of communal and casteist violence — between 2010 and 2016, Saharanpur alone saw 544 instances of communal and caste violence. Educating youth was one way to do it, but consistent, performative action — like showing strength in numbers whenever necessary — was another.

Together, Singh and Azad founded the Bhim Army, still an unregistered organisation, which began by tutoring Dalit students for two hours in the evenings. The schools are run by older Dalit students who teach younger ones in their free time. It rapidly expanded to become a quasi-administrative support service for Dalits in distress in and around Saharanpur.

In her book The Ferment, journalist Nikhila Henry describes the Bhim Army as a “well-oiled organisation that was highly regimented with all the units falling in line with the central command, the Army replicated a model which was less like national or regional political parties but was more akin to ground-level Dalit resurgence groups”.

“The Army’s number was frequently dialed up for help and the lawyer’s team was more popular than the police,” when it came to resolving issues of caste violence, she writes.

In 2017, the Bhim Army’s style of confrontation landed Azad in prison for a year, in a case that shot him to fame in the mainstream media. In April that year, Dalits of Shabbirpur village sought to install a bust of B.R. Ambedkar at the local Ravidas temple, when the Thakurs of the village objected.

A few days later, when the Thakurs organised a procession to commemorate Rajput leader Maharana Pratap, the village headman, a Dalit, opposed the loud music, leading to a scuffle that left at least 22 Dalit homes torched, and one Thakur dead.

Azad was named in 24 FIRs and went underground to evade arrest. He emerged at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar with thousands in tow in that May, commanding the attention of the mainstream media. The police apprehended him a month later, and when he finally was released on bail (the court called his arrest politically-motivated), he was slapped, the very next day, with the National Security Act and imprisoned without trial for a year.

A plea from his mother is what secured his release in 2018. By this time, mainstream activists had been vocal about their support for Azad and demanded his immediate release.

Asked how he dealt with the sudden pressure of being under the public gaze, Azad says, “I look at the progress of the movement and I forget who’s looking at me. When I look at the people around me, I feel their struggle is nothing compared to mine. If people are coming together to fight Brahmanvadi, it’s a reason to rejoice, not feel anxious.”

Also read: Modi govt’s handling of Chandrashekhar Azad & Kanhaiya Kumar shows who is the bigger threat

Numbers game

The Bhim Army’s efforts caught on in Saharanpur, and not necessarily by accident. Several political commentators say that at least in Saharanpur, the Bhim Army’s palpable presence on the ground was aided by the steady decline of the BSP.

The BSP has lost every major election from 2012 onwards, and young Dalits have grown disillusioned with the reclusive Mayawati, whom Azad claims drove the BSP to the ground.

Azad and Mayawati are both Jatavs — a Dalit sub-caste — and it has been a cause for tension. When Azad announced, for the first time, that he would stand for the 2019 Lok Sabha elections against Modi in Varanasi, and sought Mayawati’s blessings, he was stumped when she called him a “BJP stooge”.

“It’s the BJP that is fielding Bhim Army convener Chandrashekhar from the Varanasi Lok Sabha seat (as a dummy candidate) to divide the BSP’s Dalit votes,” Mayawati had said.

Although he rescinded his decision, Azad and the Bhim Army have become forces outside of conventional politics to push for Dalit representation.

Chandra Bhan Prasad, a Dalit ideologue and political commentator, says that the growth of middle-class Dalits across the country has also contributed to the BSP‘s decline and Azad’s popularity. Prasad argues that the simultaneous rise of Hindutva and middle-class Dalits has led to a new kind of conflict.

“The Dalit middle-class has acquired a certain level of education and opportunity. Caste supremacists have realised that within three generations, if there are Dalits competing even in the general category, dressing smartly, studying the sciences, it is a reason to feel contempt for Dalit people. Dalit students and IAS officers are being harassed,” says Prasad, pausing to add, “Young middle-class Dalits have statements to make. Azad is a new personality who is pioneering just that.”

This came through most notably in 2016, when Azad put up a signboard outside the neighbouring village of Gadhkauli which read, “the Proud Chamars of Gadhkauli Welcome You.”

A photo of Chandrashekhar wearing sunglasses, a crisp white shirt, fingers twirling a curled moustache and standing beside the board made for an unsettling image because it subverted every (notion/idea) associated with Dalits. The curled moustache, particularly, is a social symbol patented by the Thakurs.

By espousing it, Azad turned it on its head, revealing its hollowness. “He became the anti-thesis of the image of a helpless Dalit,” says political commentator Dilip Mandal.

“We don’t come out on the streets and demand our rights for the thrill of it. We do it because we are desperate,” Azad tells ThePrint.

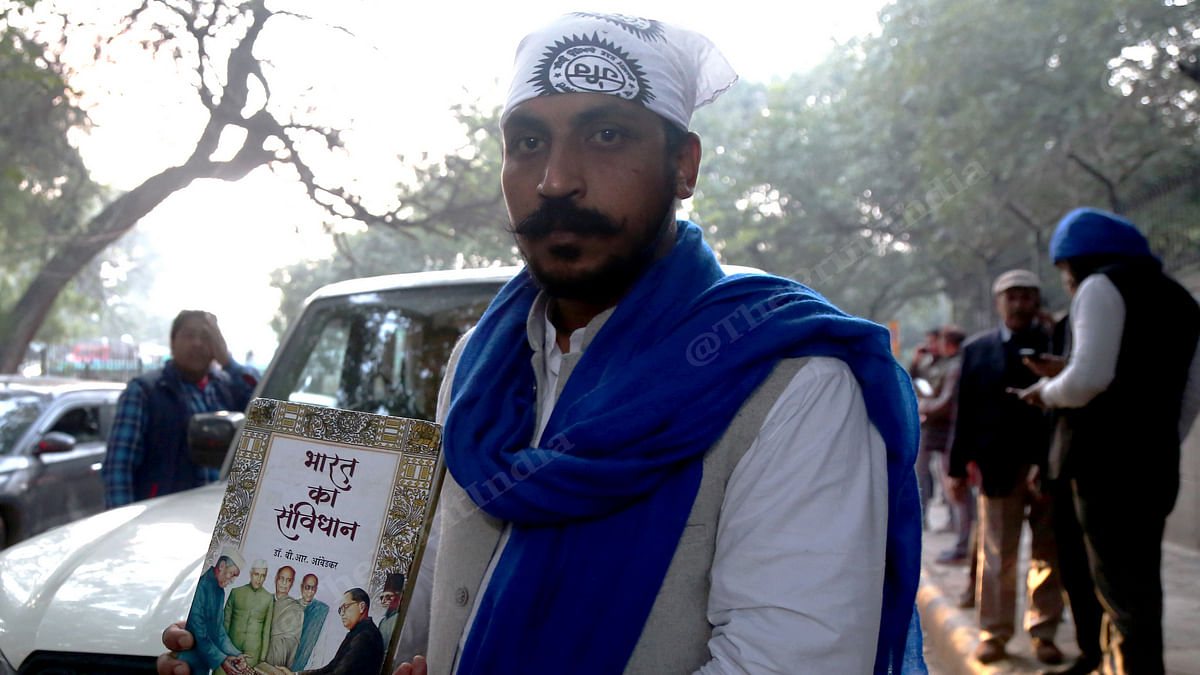

Nothing about his mannerisms and appearance betray a sense of desperation, and that’s precisely the point. “We’re entitled to dignity. Yes Dalits can dress well, can study the law, and ask for justice,” he says.

The making of a politician

Since becoming well-known across the nation, Azad has retained the Bhim Army’s aggression but has distanced himself from violence and vowed to further his cause through peaceful, Constitutional means.

His actions — of rallying the streets, being arrested and jailed only resurface with the Constitution in hand — have captivated many, particularly the media.

Part of his appeal, several supporters told ThePrint, is that he “shows up, and isn’t afraid to pay the price”.

“The more the state goes against him, the more they amplify his voice,” says Gilles Verniers, assistant professor of political science at Ashoka University.

“It allows him to indulge in forms of mild political provocation — showing up on the streets, making speeches in front of Jama Masjid. The more the state tries to suppress him, the more his popularity grows; so, in a way, he invites it through mild provocation.”

But Verniers advises some caution when looking at Azad’s rise. “He’s more of a Saharanpur and Delhi phenomenon right now, so it’s important not to exaggerate his influence,” he says. “Even if people are aware of his existence, he has a lot to do to use that goodwill and fortify it into a national movement, let alone a party.”

Azad’s aspiration to join politics has been marked by uncertainty: When he announced his participation in the Lok Sabha elections of 2019, he abruptly backed out and decided it wasn’t the right time. What follows his latest announcement is yet to be seen.

“All of his prospective voters, if he decides to stand, are with Mayawati. And they are still with her — it will take a lot of work to convince them to change their minds,” says Mandal. “It’s difficult to predict what will happen.”

Azad is, nonetheless, a compelling leader who can command the attention of thousands when he speaks. He is self-assured and patient in his dealings, earning the respect of those who follow his movements.

“I don’t lie in the movement; I’m honest with everyone around me,” Azad says. “I read the Constitution, I help people understand it. I go to jail for the things I say, so people pay attention. But I have no magic — I just listen to the people around me and do what I have to do.”

Until he takes the plunge, Azad’s sight is set on the horizon. “I wear the colour blue because it signifies equality; the ocean and the sky,” he says. “We don’t want to leave that cause. Everyone can have a piece of the sky. Dalits, too.”

(Disclosure: Mandal works as a columnist at ThePrint)

Also read: Chandrashekhar Azad writes from Tihar: Every police bullet is aimed at the Constitution

BSP should encourage the upcoming leader and strengthen them with the party’s support, as they are fighting for a similar cause