In the early 1900s, when the British proposed a plan to divide Bengal into Hindu and Muslim halves, a young boy from the Dhaka Collegiate School stood barefoot before a visiting local governor in protest. Embarrassed by the boy’s denunciations, the school authorities immediately expelled him.

Now, more than a century later, this boy is recognised by many as India’s first astrophysicist.

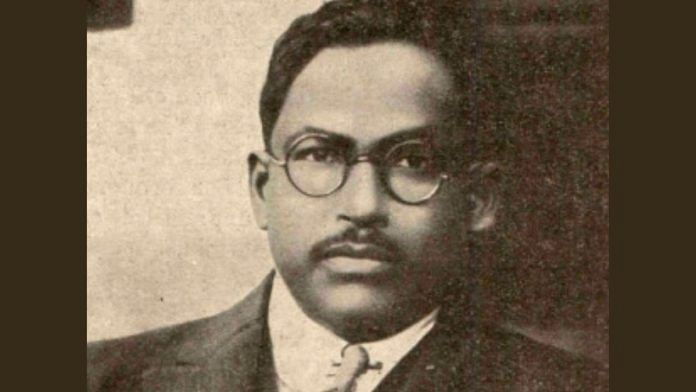

Meghnad Saha, born on 6 October 1893, has even been called the “Darwin of astronomy” by the international press. Born into a ‘lower’ caste family, he went on to become a polymath, politician, and pioneer scientist who made several seminal contributions to the world of physics. Some even consider his legacy as close to Newton’s. Later in his life, he played a big role in India’s water management projects.

“Saha is iconic in many ways,” says Somak Raychoudhury, astrophysicist and former director of the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), Pune. “He is considered India’s first ‘astrophysicist’ even though the term didn’t exist at the time.” Recalling that the scientist, who wanted to build India’s first particle accelerator was simultaneously a big voice for lower caste communities, Raychoudhury says that such inclinations are “very, very rare for a scientist”.

Also read: Cocaine, Jinnah, films, azan call—Visami Sadi set benchmark for Gujarati photo magazines

The corpus of contributions

Physicists today use the Saha ionisation equation to interpret spectra of light from the stars and gauge their temperature and composition. When Saha came up with the equation in 1920, the physics world was still learning about the interpretation of spectral lines. Raychoudhury mentions that although the sun’s spectra were identified in the 1860s and ’70s, there was no knowledge regarding the variation of spectral lines for the same element.

“His isolation equation is essentially an application of quantum mechanics to atomic physics,” he says. “Spectra vary because an element can be in different ionisation states, and the descriptions of these states could not be formulated until quantum mechanics came along. He came up with a very general formulation for how to interpret the spectra for various ionisation species of atoms.”

Saha’s work played a major role in the reorganisation of the historic stellar classification database maintained by Harvard University, which had classified stars by their size and colour from the interpretation of spectra. After Saha’s equation was published, it was picked up by the trailblazing astrophysicist Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. Using the Indian scientist’s equation, he became the first to propose that stars were made of hydrogen and helium, which went against conventional knowledge that stated the sun and Earth had a similar makeup.

Saha also opened the scientific community’s eyes to the world of plasma—often called the fourth state of matter where atoms are ionised. “Almost all of the visible universe is composed of plasma. Saha opened up the windows of our minds to the plasma universe. It is through the prism of his equation that we comprehend how the spectrum of light from stars hides clues to their chemical composition, origin and evolution,” says Dibyendu Nandi, solar physicist and head of the Center of Excellence in Space Science at IISER, Kolkata.

Apart from his contributions to science, Saha harboured ambitions to promote scientific literacy in India. In the 1930s and ’40s, he helped establish multiple societies and journals, including the National Academy of Science, Indian Physical Society, and the journal Science and Culture of which he remained the editor till his death.

Also read: Bhailal Patel—Gujarati engineer who built Vidyanagar & Sardar Patel University had no govt aid

Childhood and life

Born into a greengrocer family and victim of caste prejudice, Saha had a difficult childhood, with a lack of opportunity and intensive labour keeping him on the back foot.

The fifth of eight siblings, Saha was put to work at a young age by his father who considered schooling a waste of money. But a local doctor observed the talented boy and convinced his parents to enrol him in middle school. Young Saha’s enthusiasm was such that he would row a boat to class when monsoons flooded his village.

At Dhaka College and Kolkata’s Presidency College, where he studied, Saha faced constant discrimination from ‘upper’ caste students who even objected to him sharing the common dining hall. But the young scientist was committed to his goal. He scored top marks in astronomy and chemistry, and in college, studied thermodynamics, quantum physics, and German. Learning the foreign language helped him in his translations of Einstein’s papers into English and access to German scientific journals, which spurred his interest in thermal ionisation. But Saha did not get credit for much of his work—there was little technology in the subcontinent to verify his findings.

The astrophysicist was part of a closely knit influential scientific community—Jagadish Chandra Bose was his academic advisor and Satyendra Nath Bose his classmate at Presidency College. Bose is known for his collaboration with Einstein on electromagnetic radiation theory. Saha’s student, Samarinda Kumar Mitra, designed India’s first computer.

Saha and politics

Elected to the Lok Sabha in 1951 as an independent candidate, Meghnad Saha focused on education, healthcare, industrialisation, and water management in his constituency, North-West Calcutta. Considered the chief architect of river planning in India, he prepared the blueprint for the Damodar Valley Project. His humanist side also encouraged him to rehabilitate Partition refugees in Bengal.

A rebel from the start, Saha is believed to have aided the smuggling of guns into India to attack British troops. A non-Gandhian, he didn’t see eye-to-eye with the leader who believed scientific advancement was imperialistic. Saha had his reservations against Jawaharlal Nehru, too. The former PM worked with Homi Bhabha to design India’s atomic programme, which Saha had already worked on independently. According to Raychaudhury, Saha had attempted to get materials for a particle accelerator from the US during the Second World War, but the ship carrying them was torpedoed and never reached India.

In his later life, Saha remained dedicated to his work all the while he battled with high blood pressure. On 16 February 1956, while going to the Planning Commission office in Rashtrapati Bhavan, Saha had a heart attack. He died on the way to the hospital.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)