A.K. Fazlul Huq burst onto the Bengal political scene with such ferocity during the 1937 Provincial Assembly elections that he soon acquired the moniker, Sher-e-Bangla, or the Lion of Bengal. This was a pattern he followed for the rest of his career – defying odds and choosing paths few dared to take.

A “champion of the Bengal peasantry”, Fazlul Huq was first Mayor of Calcutta before he became the Premier of an undivided Bengal from 1937 to 1943. After Partition, he was the home minister of then Pakistan, chief minister of East Bengal, and Governor of East Pakistan from 1956 to 1958.

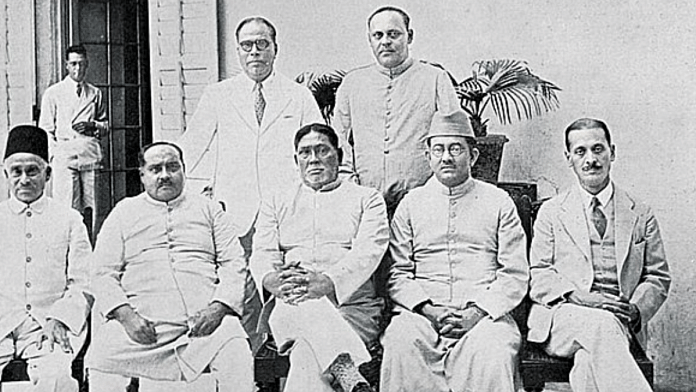

Sher-e-Bangla donned many important political hats during a tumultuous time in history. He was president of the All India Muslim League (AIML) from 1916 to 1921 and general secretary of the Indian National Congress (INC) from 1918 to 1919.

Born on 26 October 1873 in Jhalokati, a district in modern-day Bangladesh, Huq was home-schooled in his formative years. He went on to complete his Master’s in Maths from the University of Calcutta and a Bachelor’s degree in law from the University Law College.

Also read: Raaj Kumar—Bollywood prince left the police force to live a king-sized life in his white shoes

A movement for peasant freedom

A.K. Fazlul Huq started his political career with the help of Sir Khwaja Salimullah and Syed Nawab Ali Chowdhury, leading politicians with the Muslim League. But his heart wasn’t in the league.

He wanted to fight for the rights of tenanted farmers in feudal Bengal. Along with other like-minded leaders, Huq played a key role in the formation of the Krishak Praja Party (KPP), an organisation of farmers and labourers. The party was described as “not a political party, but a movement for peasant freedom and dignity.”

Huq and the KPP represented the interests of the Bengali Muslim peasantry against the more capitalistic Muslim League.

“The excitement around the 1937 election was due at least in part to the peasant populist programme of the KPP, its fierce rivalry with the Muslim League, the fiery rhetoric of its leader, AK Fazlul Huq,” historian Tariq Omar Ali said.

Fazlul Huq defeated his rival Khwaja Namizuddin in a landslide victory at the Provincial Assembly elections of 1937 receiving 70 per cent of the vote. It was not an outright victory for the KPP, but as the party was seen as an underdog, it was construed as such.

After the elections, A.K. Fazlul Huq became the prime minister of undivided British Bengal, until he was “manipulated” by British governor John Arthur Hurbert into resigning and replaced by Khwaja Nazimuddin. Hubert felt that Huq was mismanaging the administration of the province during the famine.

Also read: Atul Prasad Sen—Bengal’s forgotten musical maestro who wrote lyrics on legal papers

Adept at delivering searing speeches

The year was 1943, famine had struck. The mandate on which Huq had been elected was giving way. He had failed to uphold the rights of the peasantry. “A budget, whose figures in cold print, creep through the marrow of our bones till we stand aghast at the national calamity with which we faced,” said Huq in a 1943 speech at the Legislative Assembly.

In another fiery speech, a style that became typical of Huq, he described how “the steel frame of the Imperial service had made a mockery of authority,” accusing the governor of committing “an outrage” against the constitution.

Huq was more than adept at giving searing, heartrending speeches.

“Much has been said about the famine that hit Bengal in 1943 and killed millions. What the archives revealed to me, however, is that unchecked corruption, primarily because Huq was busy stabilising his position in his coalitions instead of serving the people, was also what made the famine worse,” said historian Dharitri Bhattacharjee.

Huq’s interests lay in maintaining his own power, and he demonstrated “incompetence and unwillingness” in actual governance. However, his popularity and sway over the people was such that even when his rhetoric didn’t translate into action, his charisma remained intact, added Bhattacharjee.

Although Huq had been outmanoeuvred, at his core, he was a wily, expedient politician who could always fall back on his linguistic prowess. In 1940, he presented the historic Lahore Resolution, the declaration of the state of Pakistan.

Conjecture or not – but as Huq made his way up to podium, he was greeted by a round of applause which drowned out Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s speech. Welcoming him with open arms, Jinnah said, “When the tiger comes, the lamb should definitely give way.”

In the 1946 elections, he won fewer seats and was defeated by another political rival, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrwadry. After partition, he settled in then capital of East Pakistan, Dhaka, and took on the post of Attorney General and continued to participate in active politics. He was a strong proponent of Bengali being made a state language in Pakistan.

However, it was not until 1954 that he returned to the fore. The East Bengal Legislative Elections were the first of its kind in newly-created Pakistan. Huq’s KPP was part of the United Front Alliance, which also included the Awami League. The mandate was astounding – the Muslim League was dramatically reduced to a few seats and in a case of a poetic justice, Huq defeated Khwaja Nazimuddin – who a few short years ago had replaced him as premier of Undivided Bengal.

Also read: ‘My name is Prem, Prem Chopra’—India’s favourite villain is more than a Bollywood bad boy

Refusal to bow down

But Sher-e-Bangla’s time in politics was approaching its end. History was repeating itself – after a few short months as the Prime Minister of East Pakistan, he was once again dismissed.

“The administration of the province had virtually broken down,” said then Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Bogra. Huq was treated viciously by the media. Dhaka’s The Mail said his dismissal “would be welcomed by every sane, true Pakistani who believes in peace, freedom and moral values.”

The Morning News in Karachi took it a step further, asserting the need for a strong centre “with enough power to arrest the process of disintegration or revolt in the provinces in which any future ‘Fazlul-Huqs’ might embark upon.”

Huq had been removed – a mere pawn – in a far larger game of chess. He had made a series of controversial statements in support of India. His unrelenting belief in his convictions and belief in empowering the peasantry, was at odds with the torrid political situation of the time.

“We are fellow workers in a common cause. If we have the common cause in view, it is idle to say that I am a Bengali, someone is a Bihari, someone is a Pakistani, and someone is something else. India exists as a whole. I shall dedicate my service to the cause of the motherland and work with those who will try to win for India – Hindustan and Pakistan – a place among the countries of the world,” said Huq in a 1954 speech in Calcutta.

A.K. Fazlul Huq’s rousing cry for unity in a freshly divided world offended many, particularly Pakistan’s central government. His refusal to bow down to the authorities, combined with the escalating security situation in East Pakistan, sealed his fate.

While he remained active, the politics of Pakistan were far too unstable. Huq was finally appointed governor of East Pakistan in 1956 and held on to the position until the coup of 1958 – after which Huq as well as his rivals, disappeared from Bengali politics.

In his account, Rajmohan Gandhi wrote of Huq alongside the two politicians that framed his political life: Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Khwaja Nazimuddin. The trio are buried together in Dhaka’s Mausoleum of Three Leaders.

“All three have been buried side by side, in the grounds of the Dhaka High Court (Huq and his political rivals). For a while, two of them were called the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Fazlul Huq was not. But only he was spoken of as the Royal Bengal Tiger.”

Huq died in Dhaka at the age of 88, leaving behind an indelible legacy.

(Edited by Tarannum Khan)