Law was Atul Prasad Sen’s calling card, but music was his enduring love. Such was his dedication and passion for music that he would often forget about his legal clients. He went on to write over 200 songs, of which only 50-60 have been sung to date.

Like Rabindranath Tagore, Rajanikanta Sen and Mukunda Das, Sen’s compositions were filled with patriotism. His songs, Moder Garob Moder Aasha and A-mori Bangla Bhaasha inspired many who were involved in the Indian struggle for independence in 1947, and even those fighting for Bangladesh’s liberation in 1971.

When Sen visited Italy, the gondola rowers of Venice inspired him to write Utho Go Bharata Lakshmi—one of his most well-known songs—which evoked the spirit of India.

His musical renditions, also known as Atulprasader Gan, earned him a place among the few poets who introduced unique styles to Indian music in the late 19th and mid-20th centuries. Sen’s songs incorporated fast Hindustani classical vocals such as Kheyal, Thumri and Dadra—his style expertly adding spontaneity to flowing melodies.

Also read:

Legal expert, musical genius

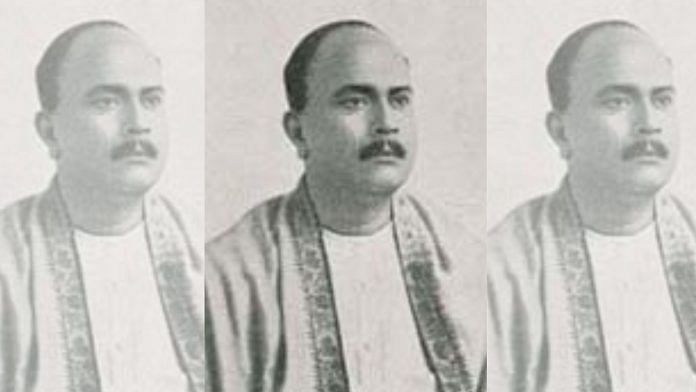

Atul Prasad Sen was born on 20 October 1871 to Ram Prasad Sen and Hemanta Shashi in the Magor village of South Bikrampur’s Faridpur district in present-day Bangladesh.

His father, who died when Sen was just a toddler, was at first a school teacher and then superintendent of the Dhaka Mental Asylum after studying psychiatry in the Bengali medium.

After his father’s death, Sen’s mother, along with him and his sisters, moved in with his maternal grandfather Kali Narayan Gupta, a renowned Brahmo social reformer and singer with a large kirtan (devotional song) troupe. It was with his grandfather that Sen realised his passion for music and spiritual songs, while his maternal uncles made him take an active interest in theatre.

Surendranath Bannerjee, a prominent Congress politician, K.G. Gupta, a relative and civil servant with the revenue board and his mother Hemanta Shashi, who worked for the upliftment of women, were among the few personalities who shaped and broadened Sen’s views on public welfare.

In 1890, Sen enrolled in Presidency College in Kolkata but eventually set sail to London to pursue a law degree. During his time there, he met and befriended prominent social reformers and freedom fighters such as Sri Aurobindo Ghosh, Sarojini Naidu and Chittaranjan Das, who he eventually joined in promoting Dadabhai Naoroji in British parliament.

Also read: Bengali poet Jibanananda Das took over Tagore’s legacy by not trying ‘too hard’

A head full of dreams

On passing his examinations in London, Sen returned to Kolkata and took an apprenticeship as Bar-at-Law under Satyendra Prasanna Sinha, more commonly known as Lord Sinha. He subsequently set up his own law practice after his step-father, Brahmo Samaj leader and social reformer Durga Mohan Das passed away.

He returned to London to work briefly as a lawyer at Old Bailey after marrying his cousin Hem Kusum—against the wishes of his family—under Scottish law in 1900. After spending two years in London, he moved back to India to finally settle down in Lucknow. This move was inspired by his friend Mumtaj Hussain, an advocate.

Sen came to be known as one of the best lawyers in Lucknow and was later elected as the president of the Oudh Bar Association and the Oudh Bar Council. Apart from being the president of the Bengal Club of Lucknow from 1903, he also was an active national-level politician for nearly 16 years.

Gopal Krishna Gokhale, president of the Indian National Congress in 1905, had a close association with Sen. This helped Sen create the Servants of India Society to deliberate on the expansion of Indian education. He played an integral role in setting up Lucknow University and a girls’ school and spent most of his income on the welfare of local people.

As successful as he was, Sen only found respite in music. “Bits of lyrics would be found among his legal papers,” wrote Chandrima S. Bhattacharya in The Telegraph.

Also read: Dilip Kumar Roy, the Cambridge-educated elite who added melody to India’s freedom movement

From courts to soirees

Atul’s music is very similar to the Tagorean style, but it was his personal experience with love and loss that added colour to his compositions. Sen’s renditions conveyed a deep sense of melancholy, most likely inspired by a painful separation from his wife. He is credited with the introduction of Thumri and Raga-based songs in the Bangla music scene, which influenced Bangladesh’s national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam and many other musicians of the time.

Sen’s legal experience did not stop him from delving into the realm of musical creativity. Holding soirees almost every evening in Lucknow, he was often joined by maestros Chhotey Munne Khan, Abdul Karim, Barkat Ali Khan and Ahammad Khalif Khan.

“I have a few memories of a visit to Lucknow, where we stayed first with my mother’s cousin, Atul Prasad Sen, and then with his sister, whom I called Chhutki Mashi. There was always music in Atul Mama’s house, for he was a lyricist and composer. Often he would get my mother to learn his songs, then write the words down for her in her black notebook. Ravi Shankar’s guru, Alauddin Khan, used to stay in Atul Mama’s house at that time,” wrote his nephew, legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray, who continued to have a lasting impression of his talented uncle. Atul Prasad Sen died in Lucknow on 26 August 1934, aged 63.

Tushar Nair is a student at the Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies. He tweets @tusharnair_. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)