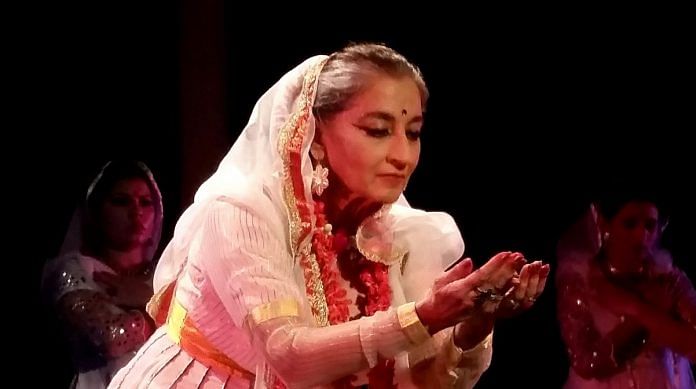

Ali Sethi is synonymous with Coke Studio, be it his soulful ‘Gulon Mein Rang Bhare’, which Arijit Singh sang in the 2014 film Haider, or his latest surprise, ‘Pasoori’. The latter is bohemian, quirky, and seems almost unlike Sethi. But what stands out in the visual bouquet in the music video is an old woman dancing in a saree.

That woman is Sheema Kermani, a Bharatanatyam dancer, feminist, and social activist in Pakistan. Her experience spans over 40 years. She is a leading figure at the annual Aurat March, a socio-political demonstration in Pakistan to observe International Women’s Day on 8 March. Kermani was a dance student in Delhi when General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq banned dance in Pakistan. When she returned to her country of birth, she started performing. “I realised that, inadvertently, my dancing became a symbol of resistance and defiance.” When the General came to power in the 1980s, among the many things he considered ‘un-Islamic’, saris were one. It was his declaration that eventually led to the attire fading out of Pakistan’s public life. Until then, saris were an integral part of Pakistani women’s wardrobe.

Ali Sethi shared the screenshot of a text message that appears to be from Sheema Kermani, and the dancer seems to be saying, “I did not want to go along the line of a literal depiction of words, but [instead] felt that the movements should be abstract but suggestive of the emotions contained within the song and music.”

Dancing as resistance

Kermani started the feminist group Tehrik-e-Niswan in the 1970s, which has used cultural interventions to create a narrative on issues of women’s rights. It also performed dhamaal, a Sufi dance, at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sindh on 16 February to mark the fifth anniversary of the 2017 suicide blast.

To Mark 5th anniversary of Sehwan blast, Tehrik-e-Niswan performed Dhamal at Lal shahbaz Qalandar's shrine.#tehrikeniswan #lalshahbazqalandar #sehwanblast pic.twitter.com/d5BB48Ee7d

— Sheema Kermani (@tehrikeniswan) February 16, 2022

Tehrik-e-Niswan started the Aurat March four years ago. “We have faced great opposition from the religious Right and increasingly more so as Aurat March becomes a political movement shaking the grounds of patriarchy,” says Kermani.

In an interview with Cutacut, Kermani said, “The discipline of the mind and body and the immense joy which comes with the freeing of the physical form is so incredible. I realised this and decided that in this very rigid and patriarchal society, dance gives me the greatest freedom to not only express but to maintain my body and soul together – to keep my sanity!”

Kermani was not sure about appearing for the video of ‘Pasoori’. “Being a classical dancer and a political activist, I was not sure if it would be the right thing to do. However, I am always open to new ideas. I did feel that it may be one way to bring dance to the youth, and I think, perhaps, it worked,” says Kermani.

Also read: Aurat March scares men of Pakistan, like the men of Iran

Saris and Pakistan

Saris in Pakistan became associated with being Indian or Hindu. While they are slowly making a comeback, they are still associated with Hinduism or ‘Indianness’. “I have been wearing saris from the time of my youth. I love it, and I feel it is my dress, and yes, it is also breaking stereotypes and making a statement about where I come from, what culture I belong to,” Sheema Kermani says.

Kermani was born in Rawalpindi, Pakistan and studied arts in London. Her maternal family belongs to Hyderabad Deccan, and saris were a major part of the women’s wardrobe.

“Dance, music and clothes should not be categorised in religious terms,” says Kermani.

India and Pakistan

After the Pulwama attack of 14 February 2019, the All Indian Cine Workers Association announced a total ban on Pakistani artists from working in India. Pakistan, too, announced a ban on screening Indian films in the country in the same year.

Despite that, people from both countries continue to consume content from across the border. Coke Studio Pakistan has been an integral part of India’s music lovers, and the craze for Ali Sethi’s latest video only proves that.

“Pakistanis have always loved to watch Indian films and we know that Indians loved to watch Pakistani TV dramas. Hatred is created between us by vested interests — the people of both countries want to live in friendship and peace,” says Sheema Kermani.

It remains to be seen if and when the ban is lifted in India and Pakistan. Until then, people who love art and culture would continue to look at the other country for cultural offerings.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)