It’s not every day that one hears stories of people’s encounters with personalities etched in Indian history. More often than not, they’re memories of a fleeting glimpse or a silent disbelief. But in her book, Father Dearest, Neelima Dalmia Adhar tells the tale of her mother, Dinesh Nandini Dalmia, actually who took to writing letters to no other than Jawaharlal Nehru. While she hid behind the pseudonym of ‘Nero’, Nehru wrote back: “Come and meet me, mysterious one. I don’t know who you are or what your name is, what you look like, or why you write to me.”

Recognition of women in the Indian literary space has been limited and is often overshadowed by the presence of influential men in their lives. For the longest time, this was the case with Dinesh Nandini too, who was married to Ramkrishna Dalmia — the renowned industrialist who founded the Dalmia Group. However, India would soon come to recognise her contribution to the literary landscape, which began as a 13-year-old and comprised 11 poetry collections, 10 novels, 10 prose songs and four short stories. She is also widely credited with pioneering prose poetry, or ‘gada kavya’, in Hindi literature. “Dinesh Nandini’s second name was ‘Surya Putri’, she was born at a time when the country was passing through a critical period…She witnessed the country pass through agni pariksha to get Independence and was involved in popularising Hindi literature till her last breath,” former Lok Sabha speaker Meira Kumar once said about her work.

Although one could identify Dinesh Nandini as a writer of Hindi literature, she was much more. Born in Udaipur on 16 February 1928, she not only battled hysteria and opisthotonus in her personal life but also actively protested against the imposition of the purdah system and gender discrimination. At a time when women were mostly confined to their homes and were not expected to have expertise in subjects beyond household chores, she became the first woman in the state of Rajasthan to achieve a Master’s degree and that too after her marriage.

Also Read: Raja Rao — the author who attempted to decipher the self through his writings

Complex relationships

According to Dinesh Nandini’s daughter, Neelima, her tumultuous personal life led her to a downward spiral.

As the sixth wife of Ramkrishna Dalmia, who is said not to have divorced any of his previous partners, Dinesh Nandini had a relationship on her hand that was beyond complex. To add to that, Dalmia’s several marriages did not make things any easier. The marriage ended after he paid his servants to spy on her after suspecting an affair between Dinesh Nandini and their children’s mathematics tutor. In fact, this wouldn’t be the first time Dinesh Nandini would be embroiled in a complex romantic relationship. As a teenager, her love for an aristocrat from Udaipur would have a profound impact on her life. His non-reciprocation is said to have spurred her literary work.

She also shared a troubled relationship with her father, who mistook her opisthotonus-induced spasms after an attempted suicide as spiritual powers and ‘divine visions’. She is said to have been labelled a ‘bal-yogini’ by the local media.

For a brief period before her marriage, Dinesh Nandini’s interest in politics led her to have correspondence with Nehru. After two years of exchanging letters, when they met, Nehru was even keen to write her a letter of recommendation to Maulana Azad, to help her kick start her career in politics.

Also Read: Vaikom Muhammad Basheer was the master of disguise. Writer to revolutionary, he did it all

Literary and social work

As an author, Dinesh Nandini seemed to have emulated the famous saying: “write what you know.” Themes of the relationship between men and women, love and patriarchy were central to her work. She was awarded the Sakseria Award for her first novel Shabnam. Her pedigree and calibre as a writer were recognised when she was invited to edit the popular Hindi literary magazine Dharmayug. In a special edition of the magazine in 1981, which discussed the phenomenon of sati, she wrote: “Through education and legal action, the gut feeling for sati practices and other customs related to sati can be stopped to a great extent. But in spite of this, there will be one or two cases of sati and people will keep on worshipping at sati mandirs. Glorification of village culture is the norm in the country. There has never been a ban on glorification nor can there be any. Along with temple construction comes the question of our citizenship with religious rights and freedom — and how can you stop that?”

After this successful stint, she even went on to start her own magazine, Richa, in 2003. She continued to work on the magazine till her death on 25 October 2007, when she was 79 years old. The same year, her last short story collection, Mantrapurush aur Anya Kahaniyan, was published.

Some of her acclaimed works include Niraash Aasha, Mujhe Maaf Karna and Yeh Bhi Jhooth Hai. Throughout her life, Dinesh Nandini won several awards, including the Mahila Sasakthikaran Puraskar by the Hindi Sahitya Akademi in 2001, the Maithilisharan Gupta award and Prem Chand award, among others. In 2005, Rani Durgavati University conferred a doctorate on her. She was even awarded the Padma Bhushan.

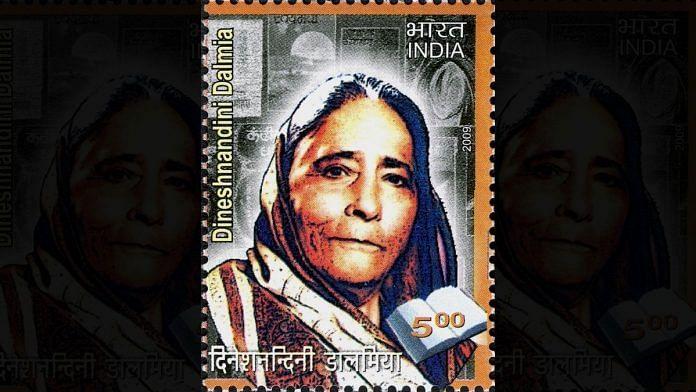

Dinesh Nandini was also an active member of the Institute of Comparative Religion and Literature and even served as its president. She was also an active participant in the Indo-China Friendship Society. In 2009, the India Post issued a commemorative stamp celebrating her life and legacy.

The absence of popularity, when it comes to Dinesh Nandini’s work, can be predominantly attributed to the fact that her writings have not been translated into English or any other language. This significantly limited her reach in the literary world. However, those who know of her and her works are appreciative of her passion. The pain that she had been dealt with in her personal life artfully reflected in her stories. She continues to be a ‘feminist icon’, as we call them today.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)