The 19th Party Congress has brought in some sweeping changes, but important questions remain over the economic and foreign policies of China.

There is a certain peculiarity in writing about Chinese politics – one’s assumptions are more prominent than the conclusions. Given the tightly-controlled propaganda machinery of the Chinesestate, there is almost no transparency in terms of how decision-making happens at the top echelons of the party.

Having said that, the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress, which concluded Wednesday, brought in some evidently sweeping changes.

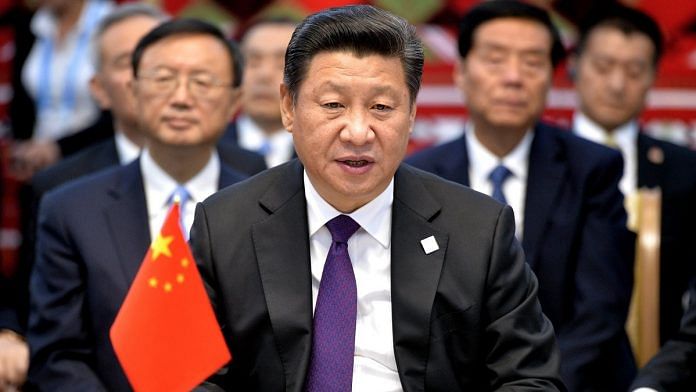

Xi abandons norms

China is often seen as a twisted version of a communist state – where the party continues to control every facet of human life, whilst allowing a market economy to exist. The Party Congress meets every five years to decide the composition of the 25-member Politburo and the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) – the highest decision making body in the state.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s era, the Party Congress has observed two informal norms. First, no party general secretary can rule for longer than two five-year terms, and second, the future leader is a part of the PSC.

Interestingly, both these norms were abandoned Wednesday. Incumbent Xi Jinping emerged as a ‘paramount leader’ – a title he shares only with Mao Zedong. The PSC has no evident heir-apparent. This has serious implications for how the party functions.

Given the nature of power consolidation by Xi and his relatively young age, the anticipation was that he would go on to rule for longer than 10 years. And this might turn out to be the case.

Either Xi will break the norm and go on to give himself another term in 2022, or he will put in place a completely new procedure of electing the next leader. There is also a third option: he might do a ‘Putin’ and appoint a loyalist as the next leader.

Interestingly, there is precedence of this in Chinese politics — Deng Xioping was said to have ruled the Chinese State much beyond his tenure via his loyalist, Jiang Zemin. It is a fair possibility Xi might choose a similar option, given his ever-growing stature in Chinese politics.

The party and the military

Beyond the leadership question, Xi has adopted a balancing act. There are two hallmarks of Chinese elite politics: the party’s domination over the military — something that has varied with different leaders — and the power within the Communist Party being shared among different factions, both at the central and regional levels.

In terms of sharing power with different factions, Xi has given way to continuity of older norms. There are prominent faces in the PSC such as Li Keiqang from the Communist Youth League faction and Han Zeng from the Shanghai faction. This tells us that Xi has agreed to share power with other factions and opted for stability. Quite possibly his consolidation of power is still incomplete. Thus, he was not in a position to fill the PSC with only his loyalists.

In terms of control over the military, Xi is a throwback to the Deng style of leadership – making him ‘paramount leader’.

Xi essentially derives his power from his control over the military. Over the last five years, he has managed to shake up some of the decades-old institutions within the military. He has purged a few power centres with his anti-corruption campaign, and filled up those spots with loyalists. We have seen some of those military loyalists being elevated to the 25-member Politburo in this recent shuffle.

Important questions

Two major questions remain: what these official changes mean for Chinese economic reforms and foreign policy.

Although, there are some prominent economic liberalisers in Xi’s PSC, like Wang Yang — this is where the lack of decision-making transparency kicks in. We cannot confidently speculate if Xi himself is an economic liberalizer, or if he’s strong enough yet to carry out the economic reforms necessary to transform China into a consumption-led economy.

In terms of China’s foreign policy, the signals are rather clear. Xi’s three-and-a-half-hour speech at the beginning of the Party Congress was a bold declaration of it. He declared the emergence of the Chinese State as the only global superpower and socialist utopia by 2050.

For India, the clearest implication cannot be missed. China is looking to establish its dominance over Asia and, eventually, the world order. The Doklam standoff and the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group snub were just early signs of it. New Delhi should expect a more belligerent Chinese foreign policy in times to come.