New Delhi: 20 minutes before noon on December 13, 2001, a white car pulled in through the gates of Parliament. It had a red command light and a sticker that appeared to identify it as an official vehicle. The security guards, well aware of the ire of officials and Members of Parliament, who they have the temerity to stop and search, allowed the vehicle to pass through without even a cursory security examination.

From the point of view of the five terrorists inside the car, armed with assault rifles, grenades and explosives, things couldn’t have become better. But then they made a small mistake. The excited driver rammed into the back of a vehicle being used by the then Vice President Krishan Kant. The driver came out of his car to argue and the police guard ordered the white car to back away.

We all know what happened next. There were gunshots and the largest military standoff since the Second World War began. Thank you for watching this episode of the Print Explorer.

Earlier this week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi lashed out at the Congress for its weakness after 26/11, the attacks in Mumbai. Today, he said, India doesn’t send dossiers. ‘Aaj Bharat ghar mein ghuske maarta hai’. Today, we go inside the houses of terrorists and hit them.

There’s a lot to debate in that particular formulation, but the one bit that interests me is that the practice of sending dossiers to Pakistan didn’t begin with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh or with 26/11.

It started with that day at Parliament House. This month in 2002, we were in the middle of that standoff when terrorists struck at the town of Kaluchak near Jammu. They killed seven bus passengers and then entered a housing complex for the families of Indian Army personnel, killing 10 children aged between 4 and 10, 8 women, and 5 soldiers.

The horrific attack was to be a turning point in the crisis, but not for the reasons you might imagine. Something very strange happened. India backed down and then India won. Why did this happen? Well, even in backing away, India got pretty much what it wanted.

In this episode, I’ll be looking at the dossier diplomacy of that period and what it got India, what it cost India. These days, diplomacy gets a bad rap, but the complex story shows that India was in fact able to obtain quite a lot of what it wanted, even if it was denied the satisfaction of seeing justice done.

Is that a price worth paying? I’ll leave that question to you to debate and decide. But the best way to kill a fish isn’t by drowning it. Covert action is necessary, sometimes. But the experience of this year shows that diplomacy and geopolitics have a big role too.

Also Read: How patriots, exiles, disgruntled officers with Japanese help laid ground for Bose to take over INA

The first dossier

There isn’t, sadly, an actual copy in circulation of the dossier that then Home Minister L.K. Advani sent to Islamabad in the days after the Parliament attack. What we do know is that it asked for 20 key terrorists to be handed over to India as the price of not going to war.

The names included key figures in organised crime like Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar and Ibrahim Razzaq Memon, jihad commanders like Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, Masood Nazar Alvi and Syed Salahuddin, various Khalistan terrorists, and the men responsible for the serial bombings in Coimbatore in 1998, which had targeted an election rally held by Mr. Advani himself.

Looking through the list today, I realised that there are some names that can now be crossed off it. Paramjit Singh Panjwar, a prominent Khalistan terrorist, was shot dead in Lahore last year, and Kandahar hijacker Zahoor Mistry, who took an Indian Airlines plane through Pakistan to Kandahar, was killed the year before that.

There was a bomb blast outside Hafiz Muhammad Saeed’s home, which Islamabad claims was carried out by India’s external intelligence agency, RAW, but he survived. Like him, all the best known names on that list of 20 are still alive, though some, by dint of sheer age, are likely to pass on any time soon.

This little doubt that this ‘ghar mein ghuske maaringe’ policy has made it quite dangerous to be even an ex-terrorist in Pakistan. For the longest time, they depended on the impunity the ISI guaranteed them. That doesn’t apply anymore.

But what benefits is it getting India? Again for that question, we have to dig deep into the story of that first dossier. Following his rise to power in 1998, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had sunk an awful lot of political capital into peacemaking with Pakistan. He travelled to Islamabad, irked some of his own hardline nationalist supporters by visiting Minar-e-Pakistan and started a bus service to Lahore.

Inside Kashmir, he ordered his intelligence services to engage secessionists in political dialogue. The Hurriyat would meet people like Mr. Advani and tried to build up the new People’s Democratic Party as a mainstream platform which would voice some of the issues that the secessionists had a monopoly over until then.

The Pakistan Army though wasn’t having all this goodwill. Even as Vajpayee was in Lahore, Pakistani troops were occupying positions on the mountains of Kargil. In spite of that war though, the Prime Minister didn’t give up. He didn’t give up even after his dialogue partner, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted in a coup by General Parvez Musharraf.

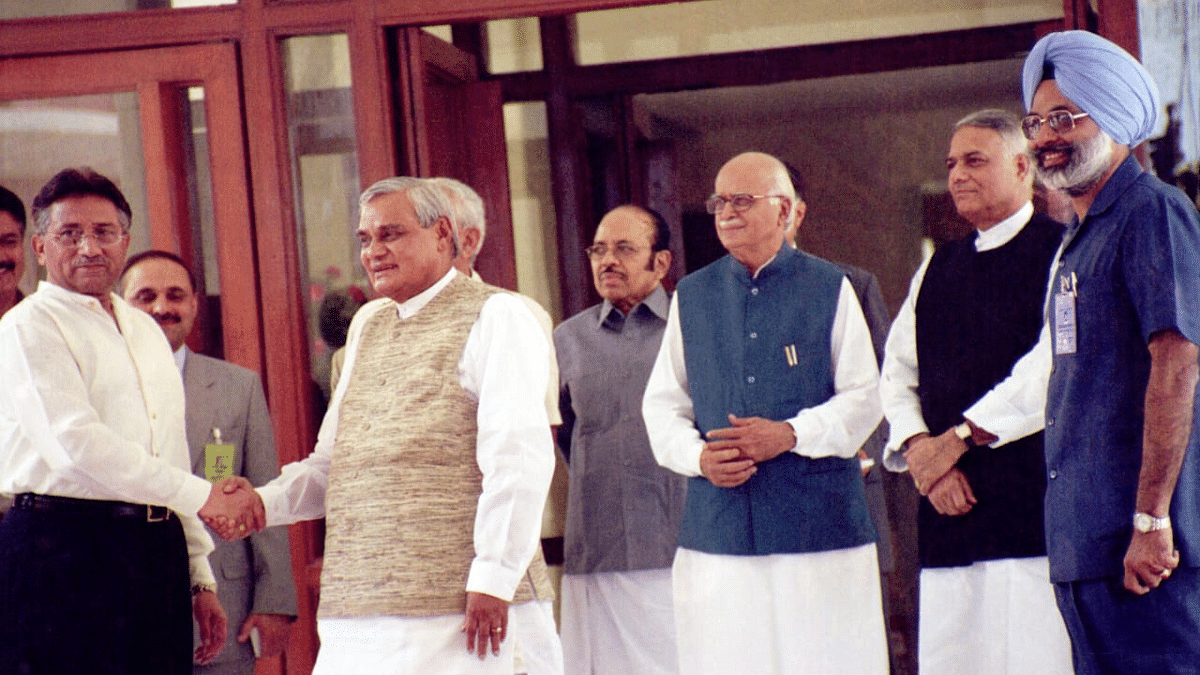

Less than six months before the attack on Parliament House, Vajpayee and Musharraf met in Agra, hoping to hammer out the framework for getting India-Pakistan rapprochement back on the tracks. There were enormous expectations but the Agra summit as it came to be known, ended in acrimony with both India and Pakistan accusing each other of being unreasonable.

The commentator B.Raman, who worked for the RAW, has pointed out that the fundamental problem was that both sides came to the table with enormously different expectations.

Vajpayee hoped for formal assurances from Musharraf that cross-border terrorism would end once and for all. Musharraf, for his part, thought that India had only come to the table because he had ratcheted up the intensity of the jihad in Kashmir after the Kargil war. He thought India was facing pain, enough pain for it to seek a solution on terms Pakistan would find acceptable. He, therefore, wanted some concessions on Jammu and Kashmir before discussing an end to terrorist violence.

Following the attack on Parliament, India’s Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS), the highest body in government on these policy issues, assembled to determine how to respond to what Prime Minister Vajpayee termed, and I quote, “the most dangerous challenge so far to India’s national security”. Pretty strong words.

In an interview with The New Yorker’s Steve Coll, Brajesh Mishra, who was then India’s national security advisor and was widely considered Vajpayee’s closest advisor, described that first CCS meeting followed the attack. He said, “we debated, we talked and we came to the conclusion that the threat of military action should be held out”.

As the Indian troop mobilisation commenced, the Indian public was very angry and clamouring for war. Indian diplomats initiated a quiet round of diplomacy aimed at avoiding exactly what the hot words were demanding. The day after the attack, Indian Foreign Secretary Chokila Iyer met with Pakistan’s senior envoy

in New Delhi, Ashraf Jehangir Qazi. Iyer told Qazi that India had evidence implicating the Lashkar-e-Taiba in the attack, which wasn’t true. It was the Jaish-e-Mohammad, and she presented a list of demands to Pakistan.

At a news conference later that day, External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh made these demands public. Pakistan, Singh told the press conference, must terminate the activities of the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad. The offices must be closed in Pakistan, their financial assets frozen, and their leaders arrested.

Pakistan’s President General Pervez Musharraf quickly condemned the attack, but his unwillingness to act on India’s demand infuriated politicians in New Delhi.

Late on the night of December 21, just a week and a bit after the attack, Prime Minister Vajpayee assembled the CCS again. During the meeting, Vajpayee decided to recall India’s High Commissioner to Pakistan.

Now, why was this important? Because the two capitals have kept envoys in each other’s countries even at the worst of times, not since the 1971 war — when the Indian Army humiliatingly crushed Pakistan — had either nation recalled its High Commissioner, and this was a pretty stark hint of how far India was willing to go.

Things then seemed set to escalate at Pakistan’s army headquarters in Rawalpindi and Musharraf’s presidential palace in Islamabad; the view became increasingly bleak. Along Pakistan’s western border, America’s Operation Enduring Freedom, which was aimed at rooting out Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, was in high gear. That meant Pakistan was already under pressure.

And now there was a threat of war on Pakistan’s eastern border where half a million Indian troops were being mobilised. In the days that followed, both President Musharraf and Prime Minister Vajpayee held out what were widely interpreted as unsettling nuclear threats to each other, both signalling how serious they were and how far they were willing to go.

Even as things appeared headed to a bloody climax though, the US persuaded India to hold back. In Washington, Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage met with India’s Ambassador Lalit Mansingh to convey that, I quote, “Musharraf will make an important statement and you will be pleased, just wait”.

Mansingh said that this gave the Indian government the impression that the US would serve as “a guarantor for Musharraf’s promises”. According to Brajesh Mishra as well, “we had been told two or three days before Musharraf’s (actual) address by the Americans, be patient and listen to what he says”.

Well, the broadcast took place on the 12th of January during an hour-long TV address that was broadcast live in both India and Pakistan. General Musharraf pledged that, and listen to the words carefully because they matter: “No organisation will be allowed to perpetuate terrorism behind the garb of the Kashmiri cause. We will take strict action against any Pakistani who is involved in terrorism inside the country or abroad.”

Now, this was exactly what India’s dossier had asked for. Now with the Americans riding Musharraf, India had got it, or seemed to have because there was a twist, because then came that horrible massacre of armed forces’s family members in Kaluchak.

After that crisis, General Musharraf made another speech saying that the export of terrorism anywhere in the world was not allowed from within Pakistan. But he angrily vowed in Urdu that, “if war is imposed, a Muslim is not afraid, he doesn’t resist, but with cries of God is great, he jumps into the war to fight.”

What do you make of that? Well, to most people listening to this address, it seemed that Musharraf was being a lot more hardline in May than he was in January and they expected that the crisis would now flare up. Following this though, Russian President Vladimir Putin met individually with both General Musharraf and Prime Minister Vajpayee at a summit. Putin urged Musharraf and Vajpayee to de-escalate.

Then the same day, Richard Armitage, the US Deputy Secretary of State, arrived in Islamabad on a shuttle diplomatic mission aimed at staving off war. The scholars Polly Nayak and Michael Krepon say that Armitage believed that “he elicited, confirmed and reconfirmed Musharraf’s pledge to make a cessation (of terrorists into Kashmir) permanent”.

So, in a nutshell, that’s the bad old dossier diplomacy, where it came from. What happened? The cost for India, it never got the 20 terrorists it asked for. It never got justice for the attacks in Kashmir, including the murder, the people who ordered the murder of those soldiers’ families or of bus passengers that same day. It did however get the de-escalation Musharraf had promised.

Levels of violence, you can see from this chart, which is based on data from the South Asia Terrorism Portal, began falling in 2002. A ceasefire kicked into place on the Line of Control (LoC), which meant Indian forward troops could patrol it much more effectively. Obviously, since they weren’t being fired at from across it and there were no artillery shells landing.

And a secret peace negotiation process began with Pakistan, where envoys for Prime Minister Vajpayee and President Musharraf began discussing a final status agreement that was meant to end the conflict. This secret negotiation would drag on for a great many years. But that’s not the burden of my story today.

The main point is, why did India get what it wanted? Well, there are all sorts of hypotheses. General Musharraf is believed to have been told by advisors like General Javed Qazi that the crisis was undermining his plans to bring about the economic reconstruction of Pakistan. Investors just wouldn’t come, his general said, if there was an atmosphere of perpetual crisis.

Perhaps, General Musharraf couldn’t resist the pressure from the Americans, or perhaps, he knew that a war with India would end with crushing defeat. Nobody after all wants to have a war which will end in annihilation for them, even if they obliterate a great part of their enemy cities.

Following 26/11, India went down exactly the same path again. The threat of war, dossiers, diplomatic meetings, joint counter-terrorism discussions; it obviously failed. Even today, none of the perpetrators of the 26/11 attacks in Pakistan have been prosecuted for their role in that particular tragedy. Many of the on-ground perpetrators, as we’ve reported in ThePrint, are still at large.

The Lashkar and Jaish, again as we’ve reported in recent days, remain active. They’ve even put up posters and held functions to commemorate the losses of jihadists they’ve sent into Kashmir. India had to suffer an Uri, a Pathankot, a Pulwama.

But wait and consider the counter-argument. India hasn’t been subjected to a major terrorist attack on any of its cities since 26/11 by the Pakistani jihadist group. The Financial Action Task Force has ensured that many of the 26/11 commanders, from Hafiz Muhammad Saeed to Sajid Mir and others, are in prison, though on terror financing charges, not on 26/11 charges.

Inside Kashmir itself, levels of violence, as we saw in that chart, are at a historic low. There hasn’t been a terrorist attack outside Kashmir since the attack on Pathankot, on the Indian Air Force base.

The two examples held out of retaliatory action, Uri and Pulwama, weren’t very clean wins either. Uri was followed, if you’ll remember, by a series of fidayeen attacks in Kashmir, which led to the losses of the lives of several soldiers. That proved that the surgical strikes, as they were called, across the LoC, didn’t put the Lashkar and Jaish out of business. Quite the contrary. And after Pulwama too, terrorists continue to operate with impunity on occasions.

There have been a string of recent attacks, for example, on the Pir Panjal mountains, where Indian troops have been ambushed.

The net-net is this, it’s complicated. The debate over offensive covert means is actually a very old one in the Indian intelligence community. And to understand why, unlike the ISI, India didn’t go down that particular road, you have to understand the history of post-Independence intelligence in our country.

India’s covert warfare

In 1947, as it left India, Imperial Britain stripped the assets of India’s covert arsenal. Documents, files, paperwork, records — everything was destroyed.

The senior most British Indian police officer in the Intelligence Bureau, Qurban Ali Khan, left for Pakistan with some sensitive files which departing British officers had neglected to destroy.

The Intelligence Bureau, Lt Gen L. P. Sen has recorded, was reduced to “a tragicomic state of helplessness”, possessing nothing but “empty racks and cupboards”. The Military Intelligence Directorate in Delhi, Lt. Gen Sen has recorded, didn’t even have a map of Jammu and Kashmir to make sense of the first radio intercepts signalling the beginning of the attacks on Kashmir in 1947-1948.

Faced with a larger and infinitely better resource neighbour though, Pakistan knew it could not compete in conventional military terms. Qurban Ali Khan’s doctrine posited that sub-conventional offensive warfare could provide a deterrence. From 1947, Pakistan engaged India in what Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru would later call “an informal war”, that is sponsoring terrorist groups both in Kashmir, in the North East and other parts of India.

It’s little remembered now, but for example, Pakistan supplied the Nizam of Hyderabad with pistols and automatic weapons to fight off Indian troops. Of course, the story of how it used raiders to attack Jammu and Kashmir rather than conventional troops is quite well-known.

Prime Minister Nehru fought the informal war using his police and intelligence services, but he generally held back, reluctant to escalate the crisis. It was pretty clear after the war of 1947-48 that though India would be superior by far to Pakistan in any war, it couldn’t inflict a decisive win. It didn’t have the military resources, it didn’t have the economic might, and even if it won a decisive victory, you’d still be left with the problem of what to do with a country of hundreds or millions of people you’d then have to look after.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi brought a different attitude to the table. She used air power for example to bomb Mizo insurgents in March 1966, killing dozens of civilians, but that’s another story.

In the wake of the 1962 war, after which technical assistance from the US and trainers from the UK became available, RAW emerged as a formidable organisation. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi wanted RAW created as an alternative to the police-dominated Intelligence Bureau and with these American assets and some French technology, RAW began working on the capability to stage deep penetration, behind the lines operations in China for which an organisation called the Special Frontier Force was set up and it also used these resources in Pakistan.

In East Pakistan, a force called Establishment 22 operating under the command of Major General Surjit Singh Uban used the Tibetans trained by the CIA to fight US-equipped Pakistani forces. Establishment 22’s personnel aided Sikkim’s accession to India, they trained Tamil terrorists, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and armed rebels operating against the pro-China regime in Burma.

Now, many of these occasions were successes or are counted by historians who’ve looked at these examples as successes. But again, just to make this story more complex, it’s worth thinking about the fact about how much backfire there was in these relationships.

For example, India’s covert support for the LTTE ended up claiming the lives of hundreds of Indian soldiers and the life of a Prime Minister.

From the early 1980s, Khalistan terrorists began receiving weapons and arms from the ISI in the middle of all this other covert stuff. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi ordered retaliation. RAW set up two covert teams known as Counter Intelligence Team X and Counter Intelligence Team J — CITX and CITJ. The first was meant for targeting Pakistan and the second in particular at Khalistani groups.

Each Khalistan terror attack on India was met as time ticked by with retaliatory attacks in Lahore or Karachi. Sarabjit Singh, who was brutally killed in an attack by fellow prisoners at a Pakistan army jail and whose killer is now being reported killed in Pakistan, was one of the people who is said though never proved to have been involved in those operations.

How do we know about these operations? Well, former RAW officer B. Raman has written that, and I quote, “The role of our covert action capability in putting an end to the ISI’s interference in Punjab by making such interference prohibitively costly is little known.” Make of that what you will.

I.K.Gujral, who became Prime Minister afterwards though, ended RAW’s offensive operations against Pakistan, and another prime minister P.V. Narasimha Rao wound up its eastern operations, that is the Myanmar side.

Why? Well, to Gujral, it seemed that India was heading into a tit for tat cul-de-sac. Sure, Pakistan would blow up a bus here and India would respond by shooting up somebody in Karachi. But that didn’t stop the attacks or inflict enough pain on Pakistan for it to hold back.

In the case of Myanmar, Rao believed that we were alienating the military junta without actually securing any influence in that country. And it meant that the Myanmarese military was responding by giving insurgents in India’s Northeast a lot of support. Even though India then continued to develop its conventional capability to deter Pakistan, it sheathed the covert sword to a very large extent.

Has Prime Minister Narendra Modi changed the rules of the game? Yes, he has. But again, not quite. It’s often imagined that India has been a passive victim of Pakistani atrocities. But on very many occasions in the past, it’s dished out just as good as it got. In Myanmar, the Indian Army staged large-scale cross-border operations in 1999 and 2006. In 2009, it pushed Northeast insurgents out of Bhutan. And Indian intelligence services have successfully operated in Nepal, Bangladesh, even in Pakistan.

The Indian Army before the surgical strike, often retaliated against atrocities but never advertised them. In May 1999, many of you may know, Captain Saurabh Kalia and five soldiers were kidnapped by Pakistani troops. Post-mortem examination revealed bodies burnt with cigarette ends and mutilated genitals, the hallmarks of torture.

Well, in January 2000, seven Pakistani soldiers were alleged to have been captured in a raid across the Neelum River. The bodies were returned, according to Pakistan, bearing signs of torture. I have no way of knowing what happened. These are just the statements from either side.

There have been a string of smaller incidents too which bear out this point. In June 2008, Pakistani troops attacked a border observation post in Poonch, killing a soldier. In retaliation, Pakistani officials allege Indian troops beheaded a Pakistani soldier on 19 June, 2008, in the Bhimbar sector.

And after some of the most atrocious communal killings in Jammu and Kashmir, there was an attack on the other side of the border too, where villagers were killed and a watch left and a chit of paper left behind with an Indian made watch that said, “how does your own blood feel?”

It’s very, very hard for a commentator or an analyst to prove what happened. But I think these cases adequately make the point that Indian forces and intelligence services have been pretty good at dishing out what India has had to put up with, if never on the same scale. You might say, well, why didn’t India do a Bombay bombings, or a 26/11, or a Parliament attack to retaliate against what Pakistan did?

The answer might be, what would India gain by doing that? It had the goodwill of the world. It would have only jeopardised it and created more instability in a situation in which actually Pakistan was falling behind India throughout the period. You might say, oh, this isn’t enough to deter Pakistan, more muscular action was needed, and you might be right. But, India’s experience has been that politics is at least as important a weapon as coercion in this game of intelligence and covert warfare.

Lessons from the past

Five rounds chambered in his rifle, constable Charandas stood watch on Srinagar’s Navakadal bridge, guarding himself against the bitter February cold with a small fire made with the remnants of a wooden crate. He paid no attention at all to the two men who walked up to him through the darkness of their night until their daggers pierced his chest. The BSF guard crawled through the snow for a few metres, his lungs biting for air before he died. Later during the night of 3 February, 1967, a policeman at the Maharajganj police station wrote up FIR 21 recording the murder.

How did India respond? Well, it destroyed al-Fateh, the terrorist network responsible for constable Das’s killing. But it did it without firing a single shot.

Figures on the fringes of that terrorist network became pillars of the establishment. Former Jammu and Kashmir Deputy Chief Minister Muzaffar Baig, eminent Supreme Court lawyer and respected political leader Bashir Ahmed Kitchloo, and even Inspector General of Police Javed Makhdoomi on whose watch a terrorist attack against Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was foiled. All these as young college students were on the edges of al-Fateh.

Following the killing of Charandas and various other terrorist actions by al-Fateh, Kashmir’s Chief Minister Syed Mir Qasim began negotiating with some of al-Fateh’s jailed operatives using the services of a very famous police officer who had broken the network, Peer Gulam Hassan Shah. Those charged with minor crimes were released, the rest provided with special facilities for their education and care at the Central Prison in Srinagar.

Later Chief Minister Qasim wrote this, “I was upset at the kinds of crimes they had committed. (But) I was also a father and, therefore, I could not take refuge under the cold crime and punishment principle”.

“I told the State Assembly on the 25th of March 1972, I can swear that I suffer the same pain as do the parents of these young people.”

The psychological operation worked. In 1975 the bulk of al-Fateh’s cadre went mainstream, forming the Inquilabi Mahaz which supported an agreement between Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Chief Minister Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah that brought an end to one part of the Kashmir conflict.

There were dissidents, but almost all of them fell in line as the months went by. “Long years of absence from employment had made a dent on my financial status,” the would-be Jihadist Fazl-ul-Haq Qureshi wrote, and, “with children to raise I wanted to stay on the job”. He resigned his position in the Secessionist People’s League; the government dropped his prosecution.

The truth is all nation states talk even as they fight. If you look through Alfred de Zayas’s excellent book on the German Army under the Nazis, you will see that the Wehrmacht, impossible as it sounds, had a division whose job it was to monitor allied war crimes. It carefully investigated allegations made by troops and some were conveyed to the allies through the Swiss government.

The allies, even more incredible, sometimes apologised for these atrocities. What was the idea behind this? Well, even as you were at war and terrible atrocities occurred, if you could mitigate some of the pain, it was something worth doing. Conflict was after all something that was about people, ending it was meant to bring dividends to people.

I’d have to be an idiot to say offensive covert means aren’t sometimes necessary. Nation states since the beginning of time have practised the assassination of enemies and used covert force to deter violence against themselves. India’s use of it in Pakistan is entirely legitimate. America, Israel, Great Britain, every other democracy on the planet does the same thing.

But sometimes we forget that force is only one among many tools. As I said, drowning isn’t necessarily the best way of killing a fish. As the debate unfolds, we should realise that the leaders who handed that dossier over to Pakistan after 2001 acted on the basis of a cold clinical assessment of what war could achieve and what they could get through diplomacy. The appraisal of gains from the use of force is vital, but only if you’re also awake to its potential costs.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Colonial legacy divided Pashtunistan. Chaman protest shows Pashtun nationalism still alive