New Delhi: In the summer of 1891, a young British journalist and military officer sent this dispatch home from the field: “We proceeded systematically, village by village. We destroyed the houses, filled up the wells, blew up the towers, cut down the great shady trees, burned the crops and broke the reservoirs in punitive devastation.

“The tribesmen sat on the mountains and sullenly watched the destruction of their homes and means of livelihood. When, however, we had to attack the villages on the sides of the mountains, they resisted fiercely and we lost for every village two or three British officers and fifteen or twenty native soldiers. Whether it was worth it, I cannot tell. At any rate, at the end of a fortnight, the valley was a desert and honour was satisfied.”

That officer’s name was Winston Churchill, who went on to be Prime Minister of Great Britain and played a huge role in world history. Welcome back to this week’s episode of ThePrint Explorer.

For the last six months, groups of villagers have been sitting at the Chaman border, on the line between Afghanistan and Pakistan, camped out in their hundreds, often without water and food, sometimes beaten by police, sometimes tear gassed. But a peaceful protest nonetheless and a long persistent one.

Why is this important? It’s because I, like every other journalist, commentators around the world and in Pakistan, devote a lot of space to talking about violence in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) and the borders of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

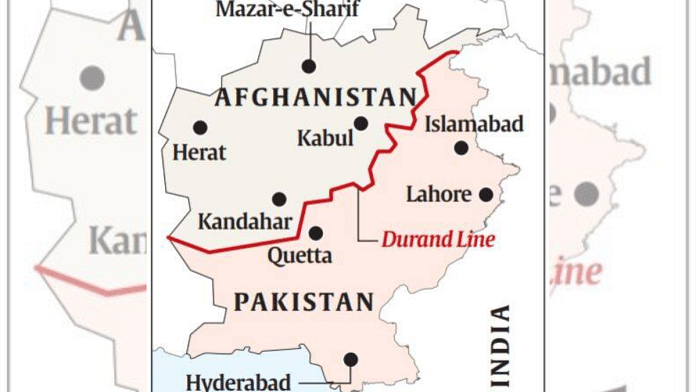

I want to look at how there have been peaceful political movements cropping up in that region and what actually is going on. The story has something to do with the Durand Line, but it’s also got something to do with the Pashtuns who straddle both sides of that border and why many of the beliefs littered across the media about war-like Pashtuns, about tribes, about codes of honour, why these are at least as much fiction as actual fact.

In fact, there’s a sophisticated political culture in the region and deep democratic aspirations that often have been put down by the rest of the world.

Last year, the Pakistan government decided that only those with valid passports and visas would be allowed to cross the border. And the reasons stated was security. The deteriorating relationship between Pakistan and the Taliban Emirate in Afghanistan are well-known.

But the transition from a pretty much open border regime to passports and visas is one which runs contrary to the ethos and traditions of the area. Pashtun families on both sides have travelled across the border for trade, for education, but also because many of them are simply visiting their kin on either side.

And because of the closure, this has brought about enormous hardships for ordinary people. The heart of the contention is the border itself, the Durand Line, and which the Taliban Emirate, just like every other government in Afghanistan, has refused to acknowledge.

The origins of the Durand Line go back to the 19th century. Even at that point, the border region between Afghanistan and Pakistan had begun to play a sort of important role in world politics. This used to be called the Great Game.

Churchill himself was an enthusiastic participant in this Great Game. And this came about because Imperial Britain believed that Russia would push southwards and eventually make a grab for India.

The backstory to this is Russia had indeed pushed forward into this independent Khanate of Central Asia, which owed notional loyalty to the Ottoman Empire. But we now know from the archives that Imperial Russia had no designs on India.

But that’s not how the British saw it. They saw another great empire sort of hovering over the jewel in the crown. And they were constantly worried at the prospect that the Russians might come to exercise influence south of the Amu Darya River and in the Kingdom of Kabul, as they called it. And they were determined not to let that happen.

In 1879, the British finally turned Afghanistan into a protectorate. To the British, it seemed that what the Soviets were interested in was the warm water ports of the Indian Ocean.

To the north, Russia had ports which were bound by ice for much of the year. And if Russia had to transition into a genuine imperial power, it needed warm water ports from which a navy could operate all the time.

Now, maintaining what was called a forward policy in the Pashtun border belt was an expensive business. And the governments of India and London weren’t always thrilled about the expense, which seemed incommensurate with the direct risk at any given point.

So there was a constant push and shove. How aggressive should Britain be in these areas? Could it manage to exercise influence through collaborators and allies? Or, did it need to be directly militarily involved? And this became a perennial question.

How could Britain protect the Indus, which runs through Pakistan? Should it annex Afghanistan as it had done with India? And how could it make sure that Afghanistan stayed secure? And this was a tough military question because had it pushed northwards, it would have required enormous military expenditure, which, as I said, the governments of India and London were not keen to engage in.

In practice, British policies by the 19th century consolidated around a vigorous defence of the Indus and periodic raids against these barbarous people as Churchill called the Pashtuns, to make sure that they didn’t rebel against the empire, raid across the Indus, and, of course, ally with Russia.

This meant having a ruler in Kabul who could be relied on by the British, who would control the buffer zone between these two great empires, but also wouldn’t come at the high price of maintaining a permanent military presence.

Unfortunately, there were multiple disastrous misjudgments by the British, which created a great deal of friction between the Afghan amirs and the empire. And things kept changing because of changes of government in London and because of the opaque distribution of power in Afghanistan itself. And the British were soon to be taught some painful lessons about their limits of power.

British India fought three wars with Afghanistan, and emerged weaker every time. In the winter of 1842, Afghan fighters completely routed the 16,000 strong army close to Kabul, which was the worst defeat ever handed out to the British colonial army.

In 1880, the Afghan tribes won another historic victory over the British army close to Maiwand, near the southern Afghan town of Kandahar. And that battle of Maiwand is still something that occupies a great deal of importance in Afghan public culture and in the emotional life of that country.

These military defeats meant that the future of the frontier remained somewhat unbalanced. Even at the end of the second Anglo-Afghan war, that’s in 1878-1880, which the British won pretty hands down, it was far from clear if you’d have a stable Afghan state which would respect a formal border with India.

And now British troops at that point controlled Kandahar in southern Afghanistan while the rest of the country was run by various tribal leaders. There were passionate debates on Afghanistan in the British Parliament.

Lord Salisbury advocated that the region should be split up into principalities. Lady Balfour wanted a second state founded alongside Afghanistan that would include Herat, Balkh, and Merv.

But once the liberals took control of the House of Commons in 1880, it was finally decided that there would be a single unitary Afghan state. This state was meant to be semi-sovereign — it would largely be independent but semi-sovereign because it would be friendly to Imperial Britain.

Also Read: Who led Islamic State terrorists to Moscow? Hitler, Stalin, CIA all helped pave the road

Foundations of modern Afghanistan

Now, this Emirate of Afghanistan was established under Amir Abdur Rehman. And you can think of it as pretty much having the same borders as modern Afghanistan.

Between 1887 and 1895, the British India and Russia laid down the foundations for this state. And the key line between the Indus and between, that is British India and Afghanistan was created by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, who created what was called the Durand Line.

Now it is important to underline that this line didn’t respect any real natural features or the ethnic boundaries of tribes or communities. It was a line of administrative convenience.

And in 1893, Abdur Rehman who was in a position of weakness having lost that second Afghan war, accepted the Durand Line. Now in Afghanistan, you will hear lots of arguments around legality of this line, about the validity of a treaty signed in a condition of military occupation among others. But those are a secondary issue.

The main point is a line of some kind had been drawn. Now where did this line come from? When the second Anglo-Afghan war had taken place, the two countries signed a treaty called the Gandamak, and it was signed by Muhammad Yaqub, the then Afghan Amir and British India.

Leaving aside the question of legality though, Amir Abdur Rehman and his vassals including the Badshah of Kunar in South Afghanistan, continued to demand taxes and declarations of loyalty from regions south of this line in areas like Chitral which were ostensibly under British sovereignty.

And it tells something important that the idea of sovereignty where a border neatly corresponds to the limits of influence of a nation state were not quite so back in that era.

Sovereignties, especially in the Himalayas which had nomadic populations, poor lines of communication, thin resources. These borders were vague and shifting, and sometimes, traditional ties and authority stretched across these borders.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, Afghan rulers continued to exert influence well on the British side of the Durand Line. Now looking at the border, it has been described by various people as an ethnic horror. Why an ethnic horror?

The Durand Line runs right through Kafiristan in the northeast region of Pakistan which has a very unique ethnic and religious population mix. In the south, it runs right through the tribal areas of the Baloch people, and it also divides the core Pashtun areas without any regard to tribal identity or sub-tribal identity.

The establishment of the Durand Line also ensured that Peshawar, the summer residence of the Afghan Amir and conquered by the Sikhs in 1835, was ceded to the British. But Peshawar had deep historical ties with Kabul which continues today.

This region was a conglomerate of numerous population segments with completely different social and cultural structures all sort of cobbled together.

In fact, there is an interesting twist in this which is even the word Afghanistan didn’t sit very well with this border.

The ‘Afghan’ is actually in the Persian language a synonym for the word ‘Pashtun’, or in the more old fashioned way ‘Pathan’. Afghanistan just meant land of the Pashtuns. The fact that the Durand Line cut right through the land of the Pashtuns splitting it into two halves was a big problem for the Afghan nation state.

The key argument for modern nationalists is that the establishment of the state of Afghanistan through an arbitrary act of colonial territorialisation was invalid. And this is an argument of many in Afghanistan and some people in the Pashtun areas of Pakistan.

So, the flames of the controversy surrounding the Durand Line were fanned by Pashtun nationalists questioning the border through the 1920s. Pashtuns with nationalist tendencies — you will hear this a lot in Pakistan — that the treaty was only going to be valid for a hundred years.

That’s not actually true. However, it should be made clear that the original treaty does not contain any stipulation of a time limit. It’s very clear that the treaty was drawn up in English in violation of international standards because it should have had a text in both languages. And it was also said that since the treaty was drawn up between Afghanistan and British India, it didn’t automatically legitimise the border since a colonial authority drew the line.

Now, the Khudai Khitmatgar or the Servants of God movement — who are called Lalkamees or Red Shirts led by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan or the frontier Gandhi — was the first major political movement to challenge this border in the 20th century. The principal aim was to dislodge the British and to establish a state of their own in the region.

After the collapse of British India, a controversial referendum was held in 1947 and the region became part of Pakistan. The foundation of a state of Pashtunistan and the option of being annexed to Afghanistan were not presented as alternatives in the ballot. The Banu Resolution, which was passed unanimously on 21 June 1947, called for the conversion of the NWFP into a sovereign state of Pashtunistan. But that assembly and declaration went nowhere.

Meanwhile, Afghanistan used the Pashtunistan question to advocate in favour of the Pashtuns inside Pakistan. As the Durand Line’s legitimacy was disputed, those in power in Kabul felt that they had a right to represent the Pashtuns inside Pakistan and to call for their right of national self-determination.

That is the Afghan Pashtuns thought that they were also speaking for the Pakistani Pashtuns, or had the right to speak for them. This wasn’t simply a division between tribes or of tribal identity. It was a modern political movement. In fact, it cut across an important division, this national Pashtun identity.

There are two kinds of Pashtuns who often self-describe in this way — the Kalang Pashtuns (those living in the plains which are in the areas around the Indus or inside Pakistan) and the Nang Pashtuns (literally means Pashtuns with honor, but it refers to the Pashtuns of the mountains to the north).

And in both of these communities, this demand for a Pashtunistan became strong. Kabul repeatedly demanded that Pashtuns in Pakistan be granted self-determination. This conflict brought Pakistan and Afghanistan to the brink of war in 1955, in 1961 and in 1977-1978.

During the 50s and 60s, Pakistan repeatedly closed its border to Afghanistan. In each case, the blockade brought Afghanistan to its knees and forced its leaders to climb down as virtually the entire Afghan export trade was handled via Karachi.

The first flashpoint came in 1949 when a loya jirga in Kabul officially declared that it did not recognise the Durand Line. In 1955, the Afghan King Zahir Shah demanded that Pashtunistan be reintegrated into Afghanistan.

And all over Kabul, there are photographs in which you can see this. People put up big posters celebrating Pashtunistan Day. In 1969, Afghanistan’s State Tourism Board published a map showing the NWFP as a part of Afghanistan.

Now, Kabul advanced historical reasons for its claim on Pashtunistan in addition to ethnic ones. For example, Afghan nationalists argued that the extent of the Durrani Empire under Ahmad Shah, and that of the ancient Aryana Empire included the NWFP.

Legal arguments were flanked by the fundamental question of exactly what Pashtunistan was made up of. At least, Pashtunistan was identified with the NWFP because its population was largely Pashtun.

Also Read: Moscow attack should raise alarm in India. Central Asian Jihadi networks inspire crime here

Deoband & Barelvi

But this wasn’t the only conception of the Pashtuns and leading into our time, a different narrative was the one that was eventually to win out.

At the same time, the Khudai Khidmatgar movement was picking up, a very different kind of current was also slowly spreading across the NWFP.

In 1915, several members of the Darul Ulum Seminary at Deoband, especially Mahmood Al-Hassan and three of his students, Hussain Ahmed Madani, Ubaidullah Sindhi and Muhammad Mia, initiated the frontier-based Jamaati Mujahideen movement.

Its aim was to finance and organise militant activity in the NWFP and provide a convenient point for the Ottoman army to open a new front against the British in the First World War.

Ubaidullah Sindhi argued that a struggle based on the unification of Islam could alone truly liberate India and defeat the British. If some of this sounds familiar, it’s because it is and these ideas were to form a big part of the jihadist narrative that would emerge in the decades after independence in both India and Pakistan.

Participants in the Jamaat-e-Mujahideen saw themselves as closely connected with the ideas and ideologies of Syed Ahmed Barelvi. In the 1820s and 1830s, Syed Ahmed Barelvi had responded to the decline of Mughal power by seeking to draw the tribes of the northwest frontier province into a jihad against the Sikhs.

He was eventually defeated at a place called Balakot, which you may remember because India and Pakistan almost went to war over there and it is a hallowed place in the jihadist imagination.

But back then, the Barelvi movement provided inspiration in the early 20th century to this new Mujahideen movement, and figures like Madani were at pains to explain that the Mujahideen movement wasn’t anti-Hindu. 20th century members of the Jamaat-e-Mujahideen stressed the religious character of the Pashtun people in the tribal areas who were mainly Muslim.

But they did not see this as part of the communal contestation that was underway which would lead to the creation of Pakistan. In fact, Deoband was quite hostile to the creation of a Pakistani state because what it really wanted was a single united Indian state in which the question of religious identity and religious and leadership of the nation was not really decided.

For example, Jamaat-e-Mujahideen leader Khurshid Ali Qasuri wrote that the Pashtuns were a true Muslim people and a model for Muslims in the rest of India. He observed that in the Pashtun lands, women could walk unafraid as no man would raise his eyes to look at them.

So, of course, quite a romantic view. But Qasuri contrasted this safety of women with that in India and also said that Pashtun society was remarkable for needing no police or a judiciary as crime was dealt with immediately by tribal panchayats.

This too, the Jamaat-e-Mujahideen leaders seem to be a kind of modern day version of the tribal society of the time of the Prophet, and they saw this as a kind of protection of the most cherished ideals of Islam.

A third strain in the NWFP was igniting on both sides of the Durand Line and this was led by various mullahs who were able to unite splintered warring tribes for common aims for short periods of time and, thus, challenge the British rule periodically.

You had Saeed Ahmad, the Haddamullah, the Turangzai Mullah among others who succeeded in turning different tribes against the British again and again and that’s one of the campaigns Churchill ended up participating in with the British put down ruthlessly often killing Pashtuns, destroying villages, killing livestock and increasingly in the 20th century with the aid of air power against civilians.

Haji Mirza Ali Khan, the famous Fakir of Ipi, led rebellions in Waziristan between 1936 and 1938. We now know that German and Italian intelligence tried to make contact through Kabul with the Fakir of Ipi during the Second World War hoping to supply him with weapons to fight the British.

The plot didn’t go anywhere but the idea was there. Many of these sort of rebellious networks were heavily influenced by folk Islam or by the traditional practice of Sufism and Sufi brotherhoods in the Pashtun area but many of these brotherhoods had connections to Deoband and the kind of ideas that the Deobandi ulema of the Jamaati Mujahideen movement were preaching.

Part of the reason for the success of this religious resistance was that under the British the institution of the tribal Malik or Sardar had become increasingly disconnected from its traditional role.

So, you will read in many places that Afghanistan is a tribal society and that the leader of a tribe is a traditional Malik but actually if you look at the tribal genealogy of the Nang Pashtun tribes, the Malik was a courtesy title not a hereditary position.

It wasn’t necessary that the son of a Malik become a Malik or that a Malik would be a Malik for life. Leadership of each tribe was much more flexible. Under the British though, the institution of the Malik became a formalised and heritable statement consolidated by the grant of lands and direct subsidies from the British colonial state.

Various scholars have actually suggested that the kind of warlordism in the NWFP is a consequence of that because it created these sort of little empires of mud where you had a leader who could extract revenues from one given area.

In the 1890s, the whole area along the Afghan-Pakistan border was divided into various pockets, each with a degree of autonomy and in 1901, the territory west of the Indus was integrated into the administration of British India as the NWFP.

And of course, the Maliks were critical to upholding this new system of British governance. Increasingly, they became disconnected from their own people.

Many urbanised, sent their children to Peshawar and elsewhere. Many developed a degree of wealth which was until then unknown in tribal society and religion often became a language of resistance for the poorer among the tribes.

Soviet invasion

Against this backdrop, we come to the third critical part which is about the Khudai-Madgar movement and how that came to be annihilated.

On Christmas Eve in 1979, Soviet troops landed at Kabul airport. Within a few hours, Afghan President Hafizullah Amin had been shot dead. Tanks and troops rolled across the Amu Darya River. And the CIA took full advantage of the chaos that emerged to support Pakistani jihadists to bring about a state of civil war.

And in this struggle that followed, Islam came to be weaponised in a way that had never happened in the past, giving the Islamist tendencies within the Pashtun belt a decisive edge.

When Pakistan was founded, the tribal areas were neglected at first and the newly founded state, despite its numerous military campaigns, never really succeeded in bringing the NWFP under full control.

Like the British, Islamabad relied on time-tested methods like bribery on the one hand and intimidation on the other to restrict the rebellions of the tribes to a tolerable minimum. They pretty much left them alone except when they became a threat at which point terrible reprisal would be delivered by the frontier corps.

But after the cessation of Bangladesh, after the war with India, the Pakistanis began to think again about this. The tribal areas were consolidated administratively as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and placed under the direct control of Pakistan’s agents.

In 1970, the Frontier Crimes Regulation was reintroduced in FATA. The socio-economic stratification of tribal society continued because Islamabad directed funds towards the Maliks, which of course led to the Maliks becoming even more segregated from their milieu than they had been in the British area.

The tribal areas barely participated in the economic development of Pakistan in the first decades after independence or whatever political rights the other peoples of Pakistan enjoyed, they did not.

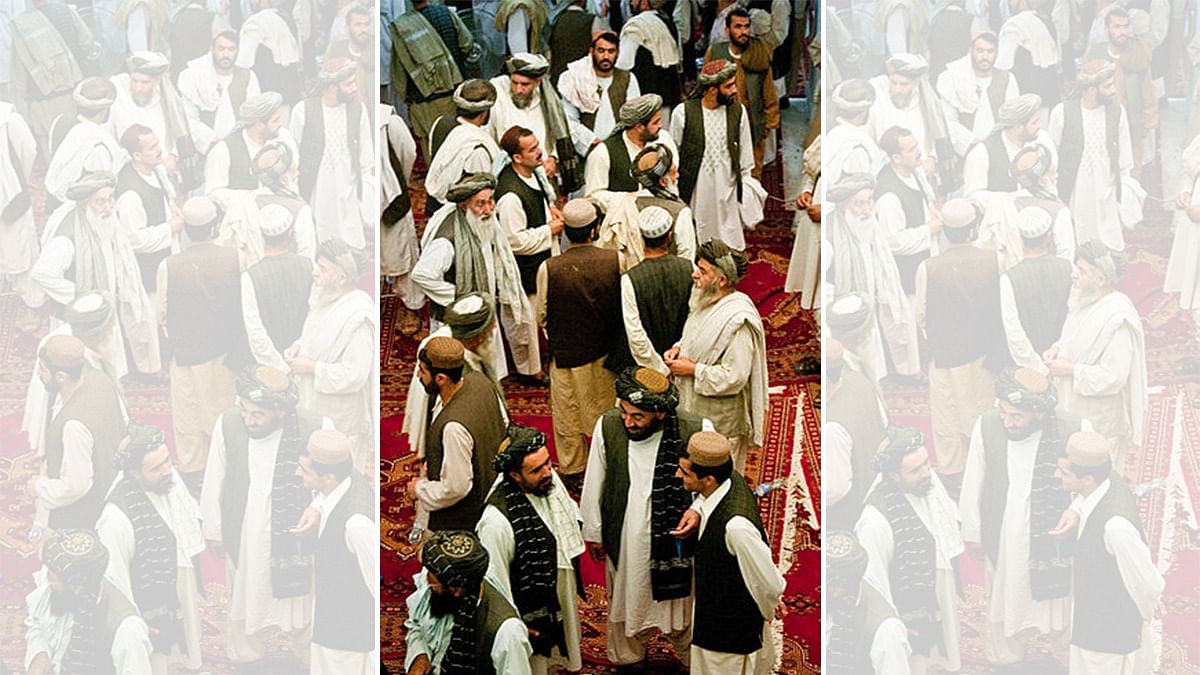

Following the Afghan Jihad and the rise of General Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq, a thorough growing process of Islamisation was put in place. To fight the Jihad. General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime turned to a coalition of Islamist parties, who had close links with Jihadists on the Afghan side as well. A lot of money was ploughed into setting up madarsas, which tilted the balance of power against the Khudai Khitmatgar movement and other Pashtun nationalist parties, who were treated with suspicion by the Pakistani military regime because of their nationalist ambitions.

The crushing of the nationalists continued for many decades on and whenever there was a sort of flickering or renaissance of nationalist thought, the Pakistan army proved willing to use Jihadists to stuff it out.

In the 2000s, General Parvez Musharraf’s regime colluded with Jihadists of what we today call the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan to carry out suicide attacks against candidates of the Awami National Party, who were standing for elections in the NWFP. The party suffered terribly.

A second phenomenon that happened is after 9/11, a lot of young Jihadists came back to the NWFP with the blessings of the Musharraf regime. They sought to displace whatever was left of the authority of the tribal Malik’s at the point of a gun. They had arms, had become used to extortion and believed that in the slogan of an Islamic state as a way of legitimising a means to grab power.

For all the Islamisation of the NWFP, today called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, for all the stories we read about the toxic communalisation and of religious indoctrination of young people by Madarsas, of all the decades of Jihad that have been fought in Afghanistan, clearly a strong nationalist impulse has still survived in the areas of Pakhtunistan on both sides of the border.

Does that mean that people would like to create a single unified state? Probably not. The Pashtuns of the plains, the Kalang Pashtuns, probably believe they are much much better off than the Nang Pashtuns of the hills who have had nothing but war and fighting.

There’s also very high levels of literacy compared to Afghanistan with the Pashtuns of Peshawar, or of the Indus plains. Certainly, they’ve acquired prosperity because of working abroad and prospering in businesses in Karachi. They will not want to give that up for some kind of idealistic nationalist pursuit.

But the Pashtun also believe that religion and Jihad are not the be all and end all of their identity. That in fact the slogan of Jihad and the promotion of Jihad by the Pakistani state has brought untold misery on both sides of the Durand Line.

What will eventually happen with this movement?

Well, we’ve seen exceptionally courageous young people as I said camped out for more than six months now on the Chaman border itself. We’ve seen youth movements fighting for democratic rights in Pakistan and we’ve seen tenacious political mobilisation against authoritarianism of the military.

As Pakistan enters a period of protracted political chaos, my guess is we’ll be hearing much more from the Pashtun areas not just in terms of guns and bombs but in terms of a determined fight back by civil society in defence of its rights to build a modern democratic polity.

Also Read: Should India talk to the new Pakistan govt? Imperfect peace is better than a crisis