New Delhi: Emerging from his DC-3 Dakota in the muggy heat of Bangkok, the young Japanese traveller was for a few moments blinded by the light of the sun, the symbol of the great empire he served.

To him, the light might have seemed like a good omen. The Tokyo he’d left behind had been grey, wrapped in the dull colours of autumn.

As he checked into his hotel room using the name Yamashita Hirokazu, the young man knew his mission could transform the fate of his nation. The man’s real name was Fujiwara Iwaichi, and he served the 8th section of the 2nd Bureau of the Imperial General Headquarters.

The job he had was to create an army of liberation, not for Japan, but for Malays, for Burmese and for Indians.

Welcome to this episode of the Print Explorer. Among the stranger election debates we’ve seen is over whether Subhash Chandra Bose should be remembered as Azad Hind or Free India’s first prime minister. Kangana Ranaut casts the spotlight on Subhash Chandra Bose and the army of liberation he led.

But its story isn’t as simple or straightforward as many of us think. For some Indian nationalists, including National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, the Indian National Army (INA) was the genuine Indian Army, unlike the British Indian Army, from which our modern military draws its heritage and traditions.

For others, particularly on the political Left, though, the INA was too deeply poisoned by the shame of being allied to fascism to be a model for the military of an independent, democratic India.

As we’ve seen in past episodes of Explorer, the truth is complex. The work of historians like Joyce Lebra, Roderick de Norman and Mellon Hauna gives reason to take the accounts we’ve grown up with sceptically.

Fujiwara, as an intelligence officer, had been responsible for handling three Indian escapees from a British prison in Hong Kong, who were given safe passage on a Japanese ship bound for Bangkok, landing there in 1940.

Once there, the exiles had contacted leaders of the fledgling Indian independence movement in Southeast Asia, as well as the Japanese military attaché. The mission had been accomplished so quietly and smoothly that the names of the three Indians were not even recorded at Japanese headquarters.

The conversations with the defectors persuaded the Japanese general staff to aid anti-British movements in India. The order issued to Fujiwara on the 18th of September 1941 read, ‘You will assist Colonel Tamura in the Malayan sector and particularly, in maintaining liaison with the anti-British Indian Independence League and with Malays and Chinese.’

To his boss, Fujiwara drafted a simple reply. ‘In order to realise the great concept of a new Asia, we’ll encourage Indian independence and Japanese-Indian cooperation, beginning with the operations in the Malayan sector.’

Following his arrival in Bangkok, Fujiwara met a young turbaned Sikh called Pritam Singh, who had himself escaped from prison in 1939. Together, Fujiwara and Pritam Singh concocted a plan to dash behind enemy lines after war began and reach Indian soldiers in the British Indian Army. The personnel for this operation would be provided by Pritam Singh’s Indian Independence League, as well as prisoners of war who were willing to join the Japanese.

Looking back, the idea might seem a bit harebrained, but it actually made perfect sense. In the 1940s, Harminder Singh Sodhi, a member of the Left-wing Kirti Party, who had been trained by the Soviet Intelligence Service, the NKVD, had conducted subversion operations among a Sikh squadron in the British Indian Army’s 21st Horse.

The work undertaken by Sodhi, military historian Philip Mason has recorded, led dozens of soldiers to mutiny in 1940 and refused service in Europe. Though the mutiny didn’t spread, it was a sign of the mood within the British Indian Army.

Even as Japanese units slogged down the muddy road to Alor Setar in Malaysia, at the beginning of their long march to Singapore and Burma and the gates of India, Pritam Singh unfurled the Indian flag at his small forward headquarters. He stood there for some time, Fujiwara would recall, in silent prayer.

The thing was, Pritam Singh didn’t have an army yet. Even though many in the Indian diaspora in Southeast Asia were supportive of the project, Pritam Singh needed soldiers. To build a military, he turned to servicemen working for the British Empire.

The beginnings of the INA

Mohan Singh, 33, had risen to the rank of captain in the 14th Punjab Regiment by 1941. He felt pride at being a commissioned officer, but also frustrated at the race-driven rules which denied him fair opportunities.

In March, Mohan Singh landed at Penang Island and from there pushed inland along with British troops to Ipoh in Perak state. After two months, the brigade moved to Sungai Patani, 75 miles south of the Malayan-Thai border.

Then, in September, the brigade advanced to Jitra, north of the front line at Alor Setar and just 16 miles south of the Malayan-Thai border. “I’m not going to die,” he told fellow officers during one brief stint of leave. “And mind you, don’t be surprised if you see me as your liberator coming down fighting the very British I’m now going to defend.”

Had the captain already made up his mind to defect? Was he a nationalist? We don’t know. But the headlong retreat of the British army led Mohan Singh, together with thousands of other soldiers, to become prisoners of war in Alor Setar.

There was chaos in the city though. Malays and Indians, long resentful of the dominance of the ethnic Chinese, took the opportunity to attack and loot their homes and properties. Fujiwara turned to Pritam Singh for help restoring order. And Pritam Singh recognised this was an opportunity to begin recruiting troops.

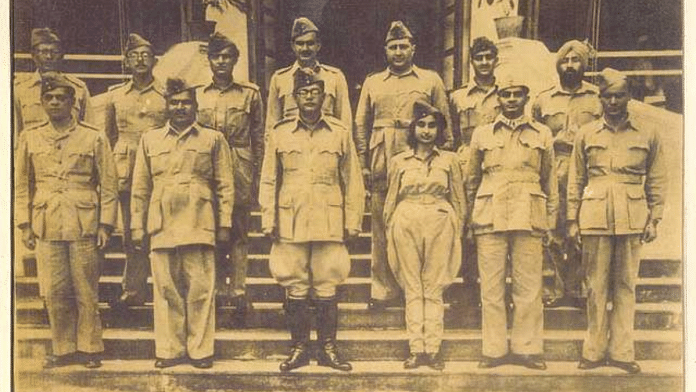

Rare pic: Captain Mohan Singh & Japanese Major Fujiwara Iwaichi meeting INA veterans in early 1970s.Major Iwaichi was head of intelligence wing of Imperial Japanese Army that helped establish Indian National Army.Mohan Singh was founder of INA & helped Sikh army veterans join… pic.twitter.com/tbFq8kUUQN

— Capitaine Haddock (@BlueBlistering) November 3, 2023

Led by Mohan Singh and his soldiers, the British Indian troops took charge of policing the city using lathis and handcuffs rather than their guns. Fujiwara and Mohan Singh now discussed the terms of a wider agreement.

In return for Japan helping to bring back Subhash Chandra Bose from Germany to the east, as well as political recognition for the new Indian army, British Indian soldiers would fight the British army on the borders of Burma. As soon as the INA reached India, Indians would surely join it and light the spark of revolution within India.

Within a few weeks, Fujiwara inspected a parade at the Faroe Park racecourse in Singapore, promising Indian prisoners of war that Japan would include their still colonised nation in a future Asian zone of co-prosperity.

Pritam and Mohan Singh also took their turns at the microphone and urged the Indian soldiers to now fight for their motherland. Their words were accompanied by continuous applause and even weeping, witnesses remember. Thousands of men and officers agreed to join the INA. Thousands, of course, didn’t.

The leaders of the new army were now taken to Tokyo to give some concrete form to the political leadership.

Tokyo & Bangkok conferences

Living in Japan since the 1920s, a small community of about 150 people, mostly students and merchants, had watched from the sidelines as a wave of nationalist sentiment grew in their homeland.

There were several Indian organisations in Japan, like the Bharat Mata Mandir in Kobe, which was a church by the way, and the Young Indian Club in Yokohama. There were also revolutionaries dotted around the country, like Rash Behari Bose, Debnath Das and A.M. Sahai, who had ended up in Japan escaping the British Empire’s police and prisons. These men and the soldiers from East Asia met in Tokyo to discuss the path forward.

From the outset, figures like Captain Mohan Singh were concerned that some Indians were being excluded. One of them was A.M.Sahai, who was the founder of the Indian National Association of Japan. Sahai had set out for the US in 1923 to complete his studies as a medical student. But, he encountered passport difficulties and never made it past Japan.

At a meeting of the Indian community in Kobe in 1929, Sahai announced the inauguration of the Japan branch of the Indian National Congress, with himself as its representative. He fell out with the Japanese though and was excluded from the Tokyo meetings.

Another missing Indian from the Tokyo meetings was Raja Mahindra Pratap. Pratap had a long career as a revolutionary. In the second decade of the 20th century, he travelled in Afghanistan and Turkey and established a provisional government of free India in Kabul back in 1918. By 1934, he was in Japan, where he founded a World Federation Centre in Tokyo.

The imperial authorities though didn’t much like him and excluded him from meetings with the INA. The concerns about the Japanese motives though didn’t stop the project from pressing forward.

In June 1942, a hundred delegates of the Indian Independence League from all over Asia assembled for a second round of discussions in Bangkok. The representatives of the two million Indians living in East Asia came from Malaya, Burma, Thailand, Java, Sumatra, Borneo, the Philippines, Nanking, Shanghai, Canton, and Hong Kong.

For nine days, they discussed plans for organising the independence movement on an Asia-wide scale. Rash Behari Bose from Tokyo was elected presiding chairman by the delegates despite the antipathy and suspicion between different groups of Indians in Southeast Asia and the ones who were already in Tokyo that had come to light during the conference. Rash Behari had, after all, instigated the Tokyo meeting.

Mohan Singh also believed his pro-Japanese leanings would be useful to help the INA’s dealings with the political leadership in Japan.

For most of this period, Subhash Chandra Bose was thousands of miles away on the sidelines of the rising INA. A message from Bose sitting in Berlin was read at the Bangkok meeting in which he referred to his 18 months of activity abroad in anti-British countries and exhorted all Indians to take up arms saying, ‘Indian independence must be attained by the hands of the Indians.’

Also Read: Colonial legacy divided Pashtunistan. Chaman protest shows Pashtun nationalism still alive

Nazi’s Indian Legion

Following his escape from Calcutta in 1941, Bose had made an incredible journey through Peshawar, Kabul and Moscow before arriving in Berlin. Finally, at a meeting with Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in April 1941, he laid out his proposals.

If the Germans would help him, he would start a government in exile and raise a free Indian army of 100,000 men. Manpower, Bose went on, would be found from prisoners of war and mass desertions. This was, of course, exactly the plan that Fujiwara had started implementing halfway across the world in Thailand.

The army Bose was raising was meant to strike at India from the West. Once the Axis had secured victory in the Middle East and the Soviet Union, Bose was given the idea, rightly or wrongly, that he would be able to operate on his own agenda in the North-West Frontier, where various tribes led by figures like the Fakir of Ipi had long waged war against the British.

Although Bose didn’t know it, Adolf Hitler had pretty similar ideas. As Hitler had planned his attack on the Soviet Union, he had already instructed his headquarters to consider an offensive through Central Asia into India.

Lieutenant General Walther Wollemont has recorded in his eyewitness memoir of serving in Nazi headquarters. The prisoners Bose needed were already available at a prisoner of war camp at Annenberg called Oflag 54.

The go-ahead for Bose from Nazi authorities came in October 1941. In the following month, this was taken a stage further. On the instigation of Hitler himself, Ribbentrop gave Bose permission to start raising his new Indian army.

The first unit was to be of battalion size, equipped and trained along German lines with German officers. Led by Gurbachan Singh Mangat, the first Indians who joined found themselves training alongside many other nationals in similar national armies, including Tajiks, Uzbeks and Persians. The first two groups were helping to form an Arab legion along the same lines as the Indians were also there.

The Indians received both basic military training and more specialised training in such areas as demolition and wireless operation. They were initially proposed to serve in North Africa, but that idea was shot down by the Nazi commander in that theatre, Erwin Rommel, a serious strategist who didn’t want the nuisance of turncoats in his ranks.

At one parade in early September 1942, Bose took the salute and presented colours to the first battalion. The Indians, according to Mangat, were given this promise by Bose, ‘I shall lead the army to India’.

The Third Reich was soon facing catastrophic losses in its war in the Soviet Union, and there was no prospect it would be able to ever march southwards to India through the Caspian and Persia. The Germans in North Africa, too, had begun marching down the long road to crushing defeat.

The Indian soldiers Bose raised ended up serving Western Europe instead, guarding Nazi-occupied Holland against invasion by the West. Three battalions of about 1,000 men each, each with three rifle companies, a heavy weapons company and a support company, huddled against the winter in the light summer uniforms they’d been issued in the expectation of heading to North Africa.

Their relationship with local people was awful. Local residents came to hate the Indians who they saw as servants of the Nazis. The Indians didn’t always help their cause with their conduct. At Anglum station, where the French resistance once attempted to hijack a train, Indian troops killed the attackers but also several French civilians.

Later, north-east of Poitiers, three Indians raped a local French girl. The three soldiers, various accounts tell us, were initially sentenced to death, but the sentence appears not to have been carried out.

Another, even worse war crime arguably, was reported from the village of Saint-Dime, east of Tours. Here the infamous three company lost one of their Indian officers who was shot in an ambush. The company responded by killing several of the men and razing the entire village.

The Indian soldiers working for the Wehrmacht, the Nazi military, behaved no differently from other soldiers in occupied Western Europe. But their visible distinctiveness made them targets for particular hatred. This was in any case no army of liberation.

Bose takes charge

Late in 1943, the historian Sugata Bose records, Bose stood on the podium at the Cathay Cinema in Singapore, dressed in a suit, tie and Gandhi cap, to proclaim himself Prime Minister of the Provisional Government of Free India. The moment marked the climax of a long journey Bose had made, from Calcutta to Kabul and on to Nazi Germany, to lead his army of liberation.

Then he travelled by submarine all the way from the Third Reich to Imperial Japan, before ending up in Rangoon. When we reach Delhi’s Red Fort and hold our victory parade there, Bose thundered: ‘No one can say who among us will be there, who among us will live to see India free.’

The German-inspired title Netaji was brought into use by his private secretary, Abid Hasan, who had come from Berlin by submarine with Bose. When members of the publicity department of the INA objected that the title might seem a little too much like Führer, Hasan agreed with them saying, ‘The role of India’s Führer is just what Subhash Bose will be.’

Even before its Führer arrived though, much of the INA was already in place. Three guerrilla brigades named after Gandhi, Nehru and Azad were already operational, as well as special groups for sabotage, intelligence and propaganda. There were medical services, reinforcements, a base hospital and an officer’s training school under Lieutenant Colonel Shahnawaz Khan.

About 17,000 troops, overwhelmingly defectors from the British, were under use and the arms they had surrendered equipped this new army. The Bangkok Resolution had demanded Japanese recognition of equal status for the INA as an allied army.

This relationship though, Tokyo never conceded. Indeed, Bose has been accused by some historians of ignoring Japanese atrocities in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Those allied with the British, of course, like the Communist Party of India, ignored the Empire’s atrocities against other Indians.

You can draw whatever conclusions you wish. Less than a year later, as news came in that his armies were falling back to the Chindwin river, Bose gathered with his cabinet at the tomb of Bahadur Shah Zafar and read the last Mughal emperor’s forlorn poem.

‘Those who were weighed in flowers morning and night,

How can they bear the thorns of grief?

They were given shackles of imprisonment

and told to embrace it as a garland of flowers.’

An army betrayed

Like all serious revolutionaries, Bose had no intention of ending up in chains like Bahadur Shah Zafar. Final victory, he continued to believe, belonged to the INA. In a ciphered message to his most trusted secret agent, located some 10,000 km away by road at Tokyo’s consulate in Kabul, Bose gave instructions for the next stage of the fight.

He envisaged a campaign of subversion targeting the British Indian Army and a war of sabotage against its infrastructure. Haji Mirza Ali Khan Wazir, the fakir of Ipi, who’d long been locked in a war with the British, was to be encouraged to intensify his rebellion and tie down more colonial troops.

Late in April 1945, Bose sent further orders. ‘I had asked you not to go in for big sabotage work, but now you can start it in a systematically planned and organised way. I and the Japanese High Command fully appreciate your efforts.’

The man who received those orders, Bhagat Ram Talwar, sent back reports with glowing accounts of the progress in building a revolutionary front within India. Talwar, however, had omitted to mention one important piece of information.

The Azad Hind Prime Minister’s most trusted secret agent was actually a spy for the Soviet intelligence service, the NKVD, and was now working on its orders for British intelligence.

Each of Talwar’s reports was actually authored by Peter Fleming, in charge of the intelligence directorate conducting deception operations for the British Supreme Allied Headquarters for Southeast Asia. Peter Fleming was the brother of the great novelist Ian Fleming, a spy and adventurer in his own right.

The superb deception operation put together by Talwar and Peter Fleming left the INA without a chance. The revolution it hoped for inside India never happened. Secret agents who came from the INA to stir up revolution inside India found they had British Intelligence Bureau officials waiting for them at the safe houses which Talwar had organised.

The final word on the INA story obviously is very, very far from being told. But enough years have passed perhaps for India to discuss the story without the ideological blinkers of either pro-Soviet communists or Hindu nationalists.

Like all entities in history, the INA was drawn with many shades of grey and had ugly blemishes on the picture. But, was it an army of liberation, or a pawn of Imperial Japan? And should India remember it as its first true national military, or as the enemy of the soldiers, also Indians, who fought with British India against Nazism? Perhaps, it was both.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: The spy who sold out Subhas Chandra Bose—he worked with Britain, Germany, USSR, Japan, Italy